Today, the destroyer is the premier surface combatant, with only a handful of navies operating larger combatant vessels of any type. Its name is a contraction of "torpedo boat destroyer", which tells us where we must look for the origins of these vessels. The self-propelled torpedo,1 invented by Robert Whitehead in the 1860s, was a revolutionary weapon. Before, the only effective weapons against a big ship were big guns, which required another big ship to carry them. Now, virtually any vessel could be armed with weapons that were able to sink a battleship.

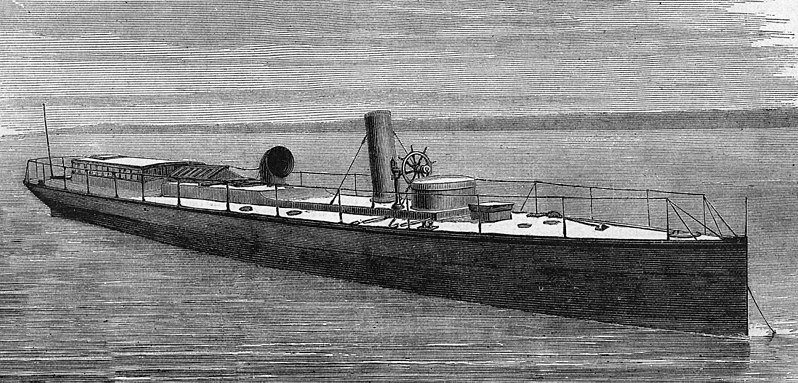

Torpedo Boat HMS Lightning

One obvious way to use this new weapon was to mount it on a small, fast vessel, which became known as the torpedo boat. The first torpedo boats, such as HMS Lightning of 1876, were extremely small, usually under 50 tons, and fast for the day, somewhere north of 18 kts. However, they were fragile and short-ranged, limitations that were often overlooked by their advocates, most notably the French Jeune Ecole, who believed that the torpedo boat had rendered the battleship obsolete. The British, who had long planned on a strategy of coastal attack, found themselves in a bind. They needed some way to keep their heavy ships safe while operating off enemy ports, and began to construct smaller ships to hunt down torpedo boats. Their first effort, known as torpedo gunboats, were built starting in the mid-1880s. They were armed with small QF guns and a few torpedoes of their own. They were seen as unsuccessful because they weren't fast enough to catch torpedo boats, although they would probably have performed well in action against their smaller, more fragile opponents.

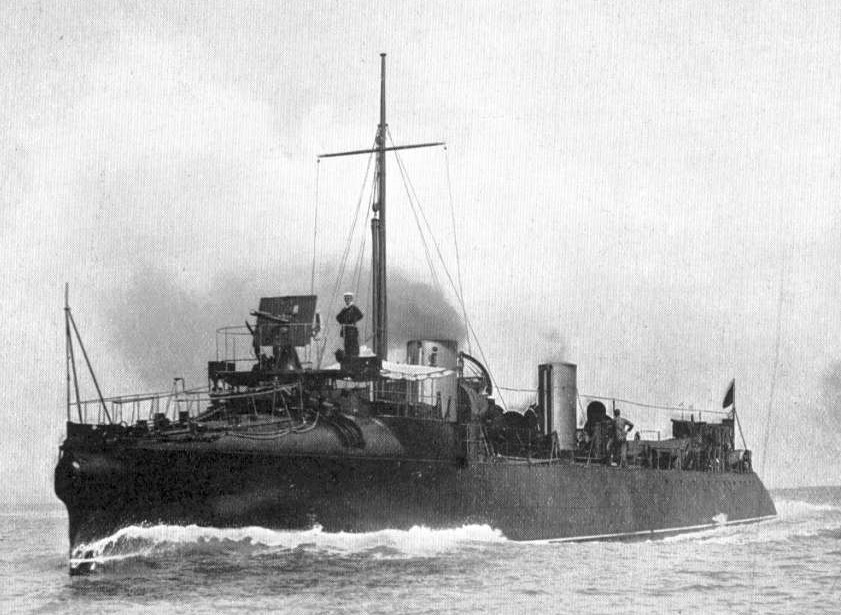

HMS Daring. Note the rounded turtleback over the bow, which was designed to shed water quickly, but mostly just made the ship wet.

At about the same time the torpedo gunboats were taking shape, a more successful solution was also on the drawing board. HMS TB 81 was laid down as a private venture in 1884, then was bought into the RN. She displaced 137 tons, about twice the size of a contemporary torpedo boat, and was armed with 4 3-pdr guns to kill smaller torpedo boats in addition to 3 torpedo tubes. This process of building bigger and bigger torpedo vessels with improved armament for fighting other torpedo boats continued for the next few years, until Jackie Fisher arrived on the scene. In 1892, as Controller of the Royal Navy,2 he ordered two classes of torpedo boat destroyer, the Darings and Havocks. These were each twice the size of TB 81, and capable of 27 kts, with a heavier QF gun armament. Water-tube boilers allowed these relatively large ships to keep up with the smaller torpedo boats, which had been powered by locomotive boilers, and their increased size and improved seakeeping made them significantly more useful than their predecessors in actual service.

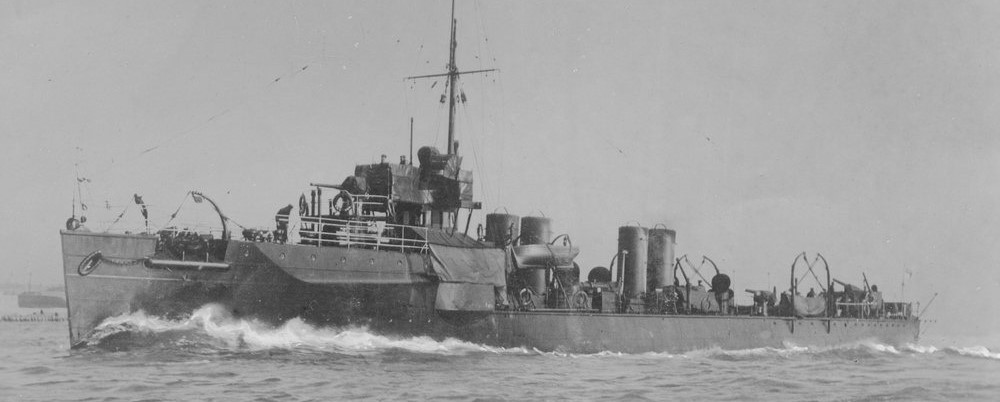

HMS Usk of the River class

These innovations were quickly copied by navies worldwide, and the Torpedo Boat Destroyer, soon shortened to just destroyer, rapidly replaced the torpedo boat as the primary platform for torpedo attack. Trial speeds quickly climbed past 30 kts, although the lightly-built vessels never got close to this in actual service, particularly as trial loads were much lighter than service loads. The next major step forward was in 1903, when the British introduced the River class. These destroyers displaced over 500 tons, and replaced the rounded turtleback forward, which was very wet, with a conventional forecastle, allowing them to make something like their design speed of 25.5 kts in service, and had the endurance to actually operate with the battle fleet. Three of these vessels also made use of steam turbines for propulsion, following the first warship to use turbines, the earlier destroyer Viper. The Rivers were followed by the Tribal class, which were close to 900 tons and armed with three 12-pdr (3") guns, a major step up in terms of gun armament. They were all equipped with steam turbines, and saw the introduction of oil fuel, which made life much easier on the stokers. Later pre-war destroyers were somewhat smaller, as the British saw the need for numbers.

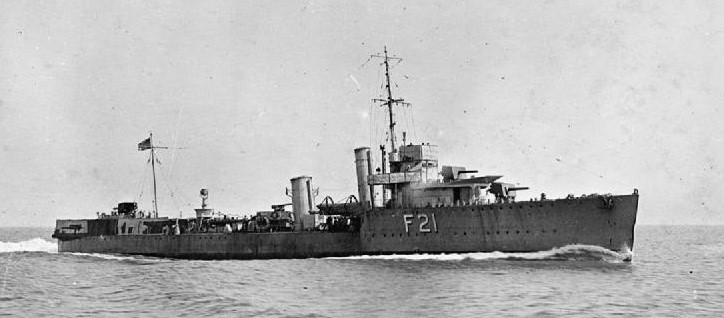

HMS Venturous of the V class

WWI confirmed destroyers as a vital element of the fleet. Besides their functions of screening and torpedo attack, displayed prominently at Jutland, their agility and speed made them invaluable in combating a new menace, the submarine. War experience led to rapid development of the type, culminating in the V and W classes of 1917. These were over 1,000 tons, armed with six torpedo tubes and 4 4" guns, and capable of 36 knots in reasonably smooth water. Many of these ships remained in service until WWII, when they were converted to escorts and battled the U-boats.

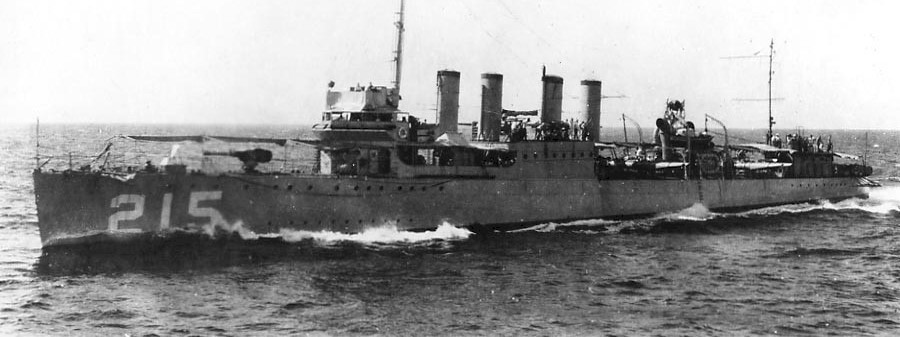

Four-piper USS Borie

The USN had taken a rather different approach with its destroyers, focusing heavily on torpedo attack. When the US entered the war, it embarked on a large destroyer-building program, producing 267 units of the Wickes and Clemson classes. These "four-pipers", so called because of their four stacks, were similar to the Vs and Ws in speed and armament, although they had 12 torpedoes and slightly greater endurance, which drove up size to around 1,200 tons. Like their British contemporaries, many survived until WWII, when they were used not only as destroyers but also convoy escorts, specialized high-speed transports, and minesweepers.

French "super-destroyer" Le Fantasque. Note how far apart the stacks are.3

From the earliest days, destroyers were intended as flotilla craft, operating in squadrons as opposed to individually. However, their limited size meant that they had no facilities for a squadron commander, and so most countries, except the United States, built specialized destroyer leaders that were slightly scaled-up versions of their contemporary destroyers, usually with an extra gun or two and some flag quarters. During the interwar years, France and Italy both built extremely large and very fast leaders, some ships reaching 40 kts. In practice, these ships fell into an awkward gap between destroyers and cruisers, and none of them were particularly useful. Meanwhile, the growth of regular destroyers meant that more conventional leaders were no longer necessary, and they were dying out by the start of WWII.

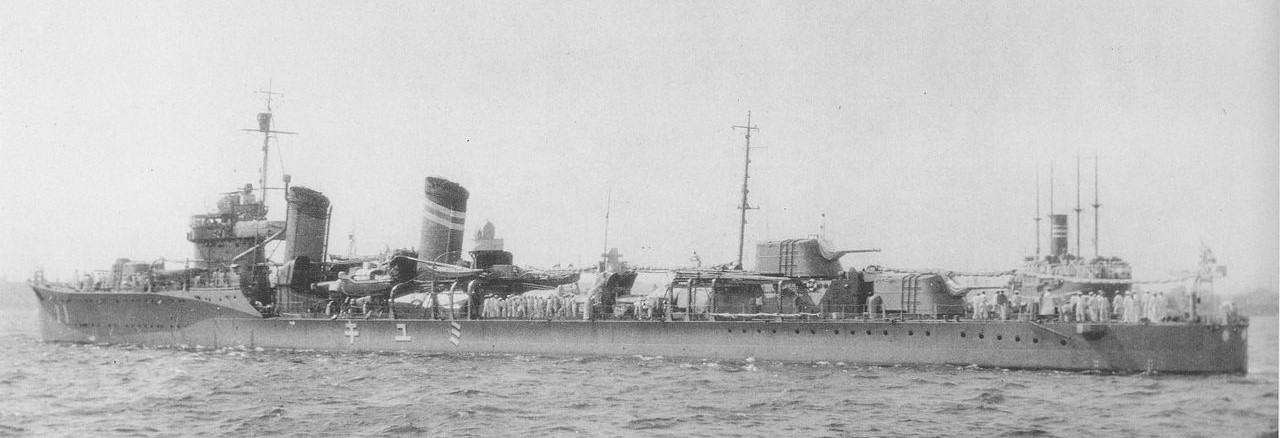

Miyuki of the Fubuki class

The next major innovation was in the late 20s, and it came from Japan. The Fubuki class were larger than previous destroyers at 1,750 tons and armed with three twin 5" gun turrets that were capable of elevating to as much as 70°, providing a useful capability against aircraft. This leap forward in gunpower was soon matched by improvements in torpedoes, which lead to the famous oxygen-powered Long Lance. This 24" weapon, the finest surface torpedo in the world, formed an important part of Japanese doctrine for the "decisive battle" and proved itself in the cataclysmic battles around Guadalcanal.

HMS Hesperus, commissioned 1937

When destroyer construction resumed in the late 1920s, the British continued the pattern laid down by the V and W classes, with minor improvements in weapons and machinery. This pattern largely held through the start of WWII, with a typical wartime destroyer being around 1,700 tons, armed with 4-5 4.7" weapons and a brace of torpedo tubes. Larger, more advanced designs had been planned, but the need for mass production in wartime meant that very few saw active service.

Flecher class destroyer William D Porter

In the US, the vast fleet of "four-pipers" meant that Congress refused to authorize more destroyer construction before 1932. The early American destroyers were broadly similar to their British contemporaries, but they were the testbeds for two technologies that would ultimately prove critical: high-temperature, high-pressure steam machinery and the superlative 5"/38 gun. Because the US was not forced to go to mass production quite as early as the British, the backbone of the wartime destroyer fleet could be of post-treaty designs, most prominently the 2,000-ton Fletcher class. The Fletchers proved to be excellent ships, big enough to deal with the massive increase in light AA guns without having to sacrifice any of their main armament of 10 torpedoes and 5 single 5" guns as earlier classes had. They were followed by the Sumner and Gearing classes, which carried 3 twin 5" mounts and an even larger light AA battery. Ultimately, these three classes, extensively refitted, would form the backbone of the US destroyer fleet into the early 1970s.

Destroyer Escort England

As in WWI, destroyers proved very useful in a wide variety of roles, from surface torpedo attack to AA screen of carriers to guarding convoys against submarines. As there were never enough of them to go around, the RN and USN both built hundreds of smaller, cheaper ships to bridge the gap. The British called their vessels frigates, while the Americans referred to their ships as destroyer escorts. Both tended to be somewhere around 1,500 tons, with a few 3-5" guns and extensive anti-submarine armament. Some carried a handful of torpedoes, but these were nowhere near as important as they were on the proper destroyers. Postwar, the importance of anti-submarine warfare was indelibly stamped in the minds of naval strategists, and "frigate" became the standard term for a ships specializing in ASW.

Soviet Kashin class destroyer Strogiy

Postwar, the destroyer continued to grow. It was the most powerful vessel still seen as affordable by cash-strapped governments, and moved firmly out of the flotilla category, taking over many of the roles previously assigned to the cruiser. Improved performance in bad weather was needed to keep up with faster submarines, and new weapons required more tonnage. The most important of these was the guided missile, and destroyers were the platform of choice for both surface-to-air and surface-to-surface weapons. Postwar destroyers ranged from 3,000 to as much as 7,000 tons, depending on role and the financial state of the government in question.4

Leander class frigate HMS Andromeda

As the destroyer moved into the cruiser's position as the high-end surface warship, the frigate became the mainstay of fleets worldwide. In the West, this was driven by the massive Soviet submarine fleet, which prompted navies to look to the transatlantic supply lines that would sustain them in case the Cold War turned hot. These vessels ranged from 2,500 to as much as 4,000 tons, and were usually armed with a 5" gun or two, some form of specialized antisubmarine weapon, an extensive sonar suite, and some form of helicopter. Later, as the WWII-surplus ships that equipped most second-rate navies were retired, general-purpose frigates usually replaced them. They were much cheaper to buy and operate than destroyers, and could fulfill the basic role of providing naval presence. Over the last few decades, this process has begun to operate in the major navies, with politicians seeing destroyers as too expensive and opting for "cheaper" frigates instead.5

USS Wayne E Meyer of the Arleigh Burke class

Today, the name "destroyer" is mostly reserved for vessels with high-end air defense capability like Aegis, while "frigate" dominates smaller vessels. Uniquely, the United States has chosen to mostly eschew frigate production in favor of the Arleigh Burke class destroyers, while most other major navies have a handful of air-defense-capable destroyers in a fleet dominated by smaller frigates.

The destroyer has come a long way from its origins in the torpedo craft, the 19th century equivalent of the modern missile boat. The one common thread of the last 130 years is that the destroyer has always been an escort, charged with keeping itself and other ships safe from asymmetric threats, be they on the surface, under the sea, or in the air. Today, it is the largest surface combatant in most navies, and a vital part of the modern fleet.

1 During much of the 19th century, any underwater explosive was known as a torpedo. The famous "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" actually referred to what we would call mines. ⇑

2 The officer responsible for procurement of new ships for the RN ⇑

3 The further apart the stacks are, the more of the ship's length is consumed by engine, and the faster it is. Le Fantasque is theoretically the fastest destroyer ever, capable of somewhere north of 40 kts, but I suspect that this was after the area she was making a run on was oiled to keep the waves down. ⇑

4 The Soviets called many of their large destroyer-derived ships "cruisers", while the US used "frigate" until 1975 when it changed "frigate" to "cruiser" and "destroyer escort" to "frigate", bringing it in line with the global standards. ⇑

5 It's fairly obvious that the name a ship has is only very loosely connected to how much it costs. That's usually determined more by capabilities, but such is the way of politics. ⇑

Comments

The US Navy also operates the Ticonderoga-class cruiser. However, looking on Wikipedia, I see that the displacement of a Ticonderoga-class cruiser is about the same as that of the later (Flight II and Flight III) Arleigh Burke destroyers. Is there any particular reason that the US Navy continues to call the Arleigh Burke class a "destroyer" rather than a "cruiser"?

Initially, the Burke was supposed to be a cheaper alternative to the Tico, and you can still see bits of this, like the fact that it has only three missile illuminators instead of four. In practice, I suspect it's basically the same political games that I mention in footnote 5. "Cruiser" sounds more expensive than "destroyer", so if we reclassify the Burkes as cruisers, it leaves a lot more space for Congresscritters to start attacking the program as a whole. Whereas if they're "cheap" "destroyers", we can keep churning them out.

(Of course, the Ticos were originally supposed to be DDGs themselves, which is why there are gaps in both the CG and DDG sequences.)

Of course, you know perfectly well that isn't true. Now, if you'd specified effective against a big enemy ship...

You're slipping. I expected you to point out not only the ram, but also the spar torpedo. And probably the towed torpedo and the naval mine, too.

In the 1860s, those were all "torpedoes". Rams were in a class by themselves. A very special class.

I think the Congresscritters are catching on: see the cancellation of the Zumwalt-class.

Also, in this classification scheme, where does something like the Littoral Combat Ship fit in? Is it more like a frigate? Or is it sufficiently different from previous classes that it's not worth trying to shoehorn it into a hierarchy that was created before anti-ship missiles?

The Zumwalts were canceled because they were useless and thus far too expensive for what we got. Only the Maine delegation disagreed, because to them they were far too useful as a jobs program.

The LCS is fundamentally a poorly-armed and rather expensive frigate that's about 50% faster than it has any rational reason to be. The successor will have a more normal speed, and be called a frigate.

What would have been the ideal US Navy plan for destroyers leading up to WW2?

I was wondering if a Somers with 3x2 DP 5"/38s and a single quad torpedo launcher would have made a good model for a mass-produced baseline fleet destroyer once the treaties ended.

That way pre-'39 construction of <1500ton destroyers could have focused on DEs, possibly dramatically reducing early-war shipping losses?

I keep looking at the huge engine costs of pushing destroyers at 33kts, and wondering what you get out of it that couldn't be done better with a hi/lo strategy of DEs and ~Atlanta-size "fleet escorts"

Pre-war, there wasn't any perceived urgency to get lots and lots of ASW hulls into the water ASAP - faster in fact than turbines could be produced for their propulsion systems - so there wasn't really any impetus to invent DEs until the war was a couple of years old.

A couple of other things the Navy lacked pre-war were sufficient money and manpower to operate large fleets of small escorts. The above "optimization" plan would only be advantageous if it resulted in a bunch more ships entering service before US entry into the war; if it instead resulted in about the same number of ships, but most of them less individually capable, that would not be advantageous.

Destroyers are escorts, which means numbers matter more than quality - you want to have one between your high-value targets and the attack, no matter what the threat axis is. But they also need to be faster than your high-value targets (e.g. aircraft carriers) so they can reposition themselves without forcing the fleet to slow down for them. You can't defend the fleet with CLAAs or superdestroyers because you won't have enough of them, and you can't defend the fleet with DEs, because they'll be trailing far behind it.

And, of course, they need to defend against air, surface, and submarine threats.

For actual destroyers, the US prewar Farragut through Sims class look pretty good, except that wartime experience showed that they needed to trade down to 4x5" guns and ~10 torpedo tubes to add K-guns and 40mm Bofors. If we imagine unusually prescient designers, that could have been built in to the original design, but it was an easy enough modification to make.

A high-low mix with Farragut-Sims style destroyers and Evarts/Buckley DEs would have been wise, as there were obviously going to be merchant convoys, amphibious task forces, etc, that needed escorting but didn't need 34-knot escorts.

DEs also had smaller turning circles than DDs, by much more than size alone would imply (vaguely remembered from Friedman: DE ~350yd, DD ~700yd, BB ~700yd). It seems plausible (though I don't actually know) that this was because narrow-and-deep hulls were faster in a straight line but harder to turn than wide-and-shallow hulls, and hence that a DD's speed-optimized design was actively harmful (not just a waste of money) for ASW work.

A tight turning circle was useful for aiming by turning the entire ship (then the norm for ASW weapons), and possibly for dodging if the submarine tried to torpedo you. (Though the latter risk seems to have been nonzero but smaller than I'd expect from running right over a hostile submarine - possibly the submarine couldn't effectively aim while trying to dodge depth charges and wasn't usually willing to go for mutual destruction, possibly they'd rather spend their limited supply of torpedoes on merchants??)