The men aboard the destroyers aground at Honda were in a perilous situation. Some of them were aboard ships still in reasonable shape, although that would change as the hulls worked against the rocks. Others, particularly the men crouched on the upturned side of Young, were in imminent danger of being washed into the pounding seas. All would have to try to reach safety, although for most of them, it was unclear what that would mean, beyond a less exposed position, maybe at the top of the cliffs. The general consensus was that they were aground somewhere like the uninhabited San Miguel Island.

First to begin evacuation was the crew of the S.P. Lee, their ship listing 30° and with waves breaking entirely over the ship. The first threat came from the crippled Nicholas, which was bearing down on the Lee before an encounter with a pinnacle of rock stopped Nicholas clear of her sister. But if Nicholas broke loose, Lee would suffer heavy casualties, and even if she didn't, the pounding surf would soon make Lee untenable. Only 50' separated her from the cliffs, but it was a maelstrom of swirling water. Two men fought their way across in a rubber raft, securing a line to the rocks, although there was only a narrow ledge of rock to land on and no obvious route to the top of the 100' cliffs. While they did this and returned aboard Lee, a signalman aboard her made contact with Nicholas by blinker, and it was reported that the second destroyer was fast aground, but in no immediate danger, so it was decided that, barring a change in her situation, her crew would remain aboard until daylight.

The two sailors who had made the initial crossing volunteered to go back and find a path up the steep, jagged cliffs while others rigged a ferry using the Lee's Carley Floats, with the men aboard each hauling themselves along the line between ship and shore. After a few minutes, the two explorers found a reasonable path off the ledge, and the rest of the men began to slow trek to the top of the mesa. Many had been in their racks and lacked shoes and clothes, and the battering surf and sharp rocks left cuts and bruises. As the senior officers boarded the last raft, a whistle echoed off the cliffs. It was the product of a passing train, and its presence told the men aboard all of the destroyers that they were on the mainland, and that help was closer at hand than they expected.

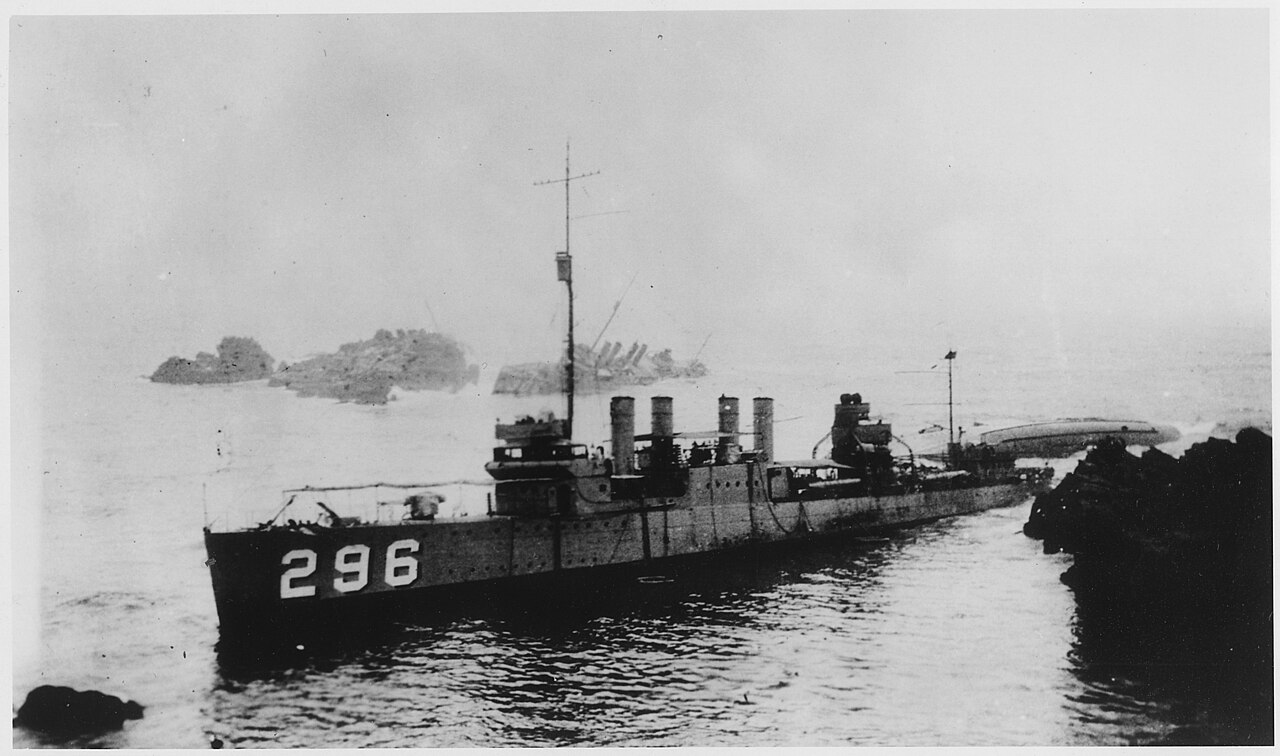

Nicholas (left) and Lee

In fact, help was already on the way. A Section House for the Southern Pacific Railroad was perched atop Honda Mesa, and its foreman was on his way to bed when he saw a flash from the sea and heard a sound that might be a crash of some sort. He went to investigate, running the half-mile down to the edge of the mesa, and although the ships were shrouded by fog, he could smell the greasy smoke of oil-fired boilers. Eventually, the fog parted to reveal the unmistakable stacks and guns of the Lee, sending the foreman racing back to the section house to pass the word to the outside world. His first calls went to the town of Surf, five miles to the north, where his superior immediately took responsibility for arranging help and told the foreman to take his section of workers down to the cliffs to help in the rescue. Surf was a small town, and men and supplies were requested from Lompoc and San Luis Obispo, further to the north. An attempt to pass the message to the Navy failed when they disregarded it as a duplicate report of the grounding of a civilian ship the previous day.

The team from the Section House arrived as the crew of the Lee reached the top of the cliffs, and quickly arranged to evacuate the worst-hurt to the shelter of the trees near the Section House, where bonfires could be built with the railroad ties piled nearby. The foreman passed the first firm reports of the disaster up the line, although he only knew for certain that three destroyers - Lee, Nicholas and Delphy, were aground. It was only shortly after the last of the men from the Lee reached the cliff that the first responders from outside arrived in the form of some railroad personnel from Surf and the police chief and newspaper editor from Lompoc. They had arrived in a motorized track car, which at one point they had needed to manhandle off the track to get out of the way of the passing train. The first man they encountered was Captain Robert Morris, commander of DesDiv 33, off of the Lee, who was taken to the Section House to give the first complete reports of what would be needed, information that reached not only the railroad men preparing to render aid, but also the Navy and the nation's news organizations.

Delphy (foreground) and Young

While all of this was going on, the crew of Delphy were working desperately to reach safety before their ship was pounded to pieces. A few sailors managed to jump to a nearby rock before the ship moved away, and others found themselves in the churning water alongside, struggling against the thick oil leaking from the destroyer's punctured tanks. Two of their fellows went to the rescue, but one, James Pearson, shattered his glasses while diving in, and shards of the lenses were embedded in his eyes. The other managed to get everyone out using the ladder rungs welded to the hull, although rescuing Pearson, mad with pain, was particularly difficult, and his struggles made it impossible to get him off the ship. Eventually, the decision was made to lash Pearson to the ship in the hopes of getting him to shore in the morning. Meanwhile, a sailor set out for a nearby rock, eventually covering the 20' gap despite being twice swept under the hull. A line was rigged despite the pounding waves, and the process of abandoning Delphy began. Each man had to go hand-over-hand along the line, while a group aboard the rock kept it taut despite Delphy's rolling. Only one failed to make the trip, as an unexpected roll dropped him onto the rock, then snapped the line back and threw him into the air. The oil coating everything made it impossible for the other sailors to save him before he was swept out to sea. A second man fell, but was rescued by the quick actions of three others, while a third was drowned by the thickening blanket of oil. From the rock, a second line was rigged to the cliffs ashore, but the hand-over-hand trip along it was far less perilous and everyone who made the rock reached the cliffs safely. Getting up the cliffs was no easier than it had been for the crew of the Lee, and the few sailors who had shoes on were appointed to carry their fellows to higher ground. Initially, the plan was to remain close to the ship in hopes of conducting salvage operations, but the locomotive whistle was incentive enough to explore further, and the survivors of Delphy soon made contact with the crew of the Lee and began to shelter alongside them around the fires by the railroad tracks. When the fog cleared the next morning, Delphy had broken in half, and Pearson was gone.

But it was those aboard Young who were in the greatest peril. The 80 or so survivors, clinging to the port size of the capsized destroyer, had only a few smashed portholes for handholds as waves washed over them. The hemp lifelines on the bow were quickly appropriated to lash the men together, and one of the officers volunteered to swim the 100 yards to shore. As they were getting lines together for the task, Chauncey appeared out of the darkness, coming so close that Young's propeller gashed her side. Chauncey came to rest on the rocks nearby, diverting the receding surf from Young and providing a place of relative safety only 75 yards from the capsized ship.

Chauncey, Young and Woodbury

Chauncey’s captain quickly set to work to both get his crew ashore and aid those aboard Young. Lines were quickly put across the 25-yard gap to the rocks, and two liferafts were used to ferry the crew ashore. Chauncey was in a better position than some of the other ships, and despite the fact that she was the last ship to go aground, her men began to reach the top of the bluff not long after those from Delphy. A few remained aboard to launch the whaleboat, but before they could set off for the Young, a wave smashed it to pieces. The line would instead be carried by one of Young’s chiefs, who swam the distance between the two destroyers. A raft from Chauncey was used as a ferry, with men on each end hauling it back and forth, a total of 11 trips to evacuate the entire crew of the Young, who then had to be taken to shore and helped up the cliffs by the crews of Chauncey and Delphy, soon joined by the first of the railroad crews from San Luis Obispo. The same train had brought a pair of doctors from Lompoc, who joined the destroyers' Pharmacist Mates in aiding the wounded.

As far as those ashore knew, five destroyers had run aground, and the crews of four had managed to reach safety, with the men trickling into the fires near the Section House. But they were unaware that two more ships had struck the rocks further offshore. We will pick up the story of their crews next time.

Comments

I find this so interesting, and sad.

Excellent work Bean, keep it up! Love your posts.

The more detail you read about any of these events, the more you see the 1-in-100 guys who somehow did the impossible to save everyone else. And half the time nobody bothered to record their names.

The names are recorded in this case. My main source was the book Tragedy at Honda, and it goes into a lot more detail. I just cut them for narrative flow.

@Bernd: several were recommended for medals. (I don't know if any of these were actually awarded.)