Operating planes off of a ship is tricky. Planes only work well when flying at speed, and unlike on land, there isn't a lot of space for a runway. It turned out that while flying planes off ships was relatively straightforward, landing them back aboard was very difficult. The solution was to attach floats the plane, which allowed it to not only land on the open sea, but also take off while the carrier was anchored, a common condition in the early days of naval aviation.

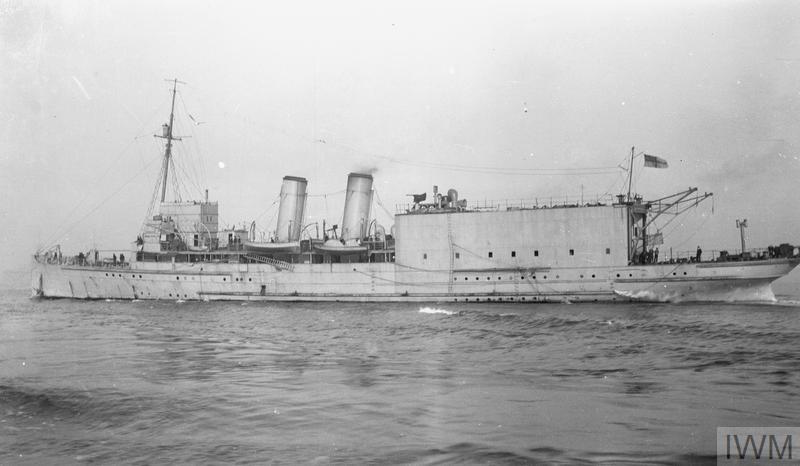

Seaplane carrier Engadine

But while using the sea as a runway worked well for anchored ships, it was far less suitable for operations with the fleet. The carrier would have to stop and hoist the plane in or out, costing it ground relative to the rest of the fleet, and all of the ships suitable for carrier conversion were too slow to regain position reliably. Also, while an anchored carrier would generally be somewhere protected from the worst of the ocean's waves, this was definitely not the case for a seaplane carrier operating in support of the fleet. In particular, taking off from the open ocean in any sort of sea is extremely tricky, to the point that the wakes of nearby ships might disrupt the operation. These problems were dramatically illustrated by the first serious attempt to use airplanes in concert with the fleet during the Battle of Jutland.

A Sopwith Camel on a flying-off platform aboard HMS Tiger

In the long term, this was a problem that would need to be solved by the procurement of suitable carriers, but as an interim solution, the British began flying landplanes from platforms mounted atop the turrets of their battleships. The turret itself could be used as a turntable, aligning the platform with the wind and generally guaranteeing at least 25 kts wind over deck without the ship having to leave the fleet, which, combined with improvements in engines, was enough for a plane to get airborne in the 70' or so a turret-top platform allowed. Of course, there was no way to get the plane back aboard the ship, and it would either be flow to a land base (if one was in range) or simply ditched at the end of its flight. The planes of the day were quite cheap, and the ability to shoot down Zeppelins and spot enemy warships was worth the cost.

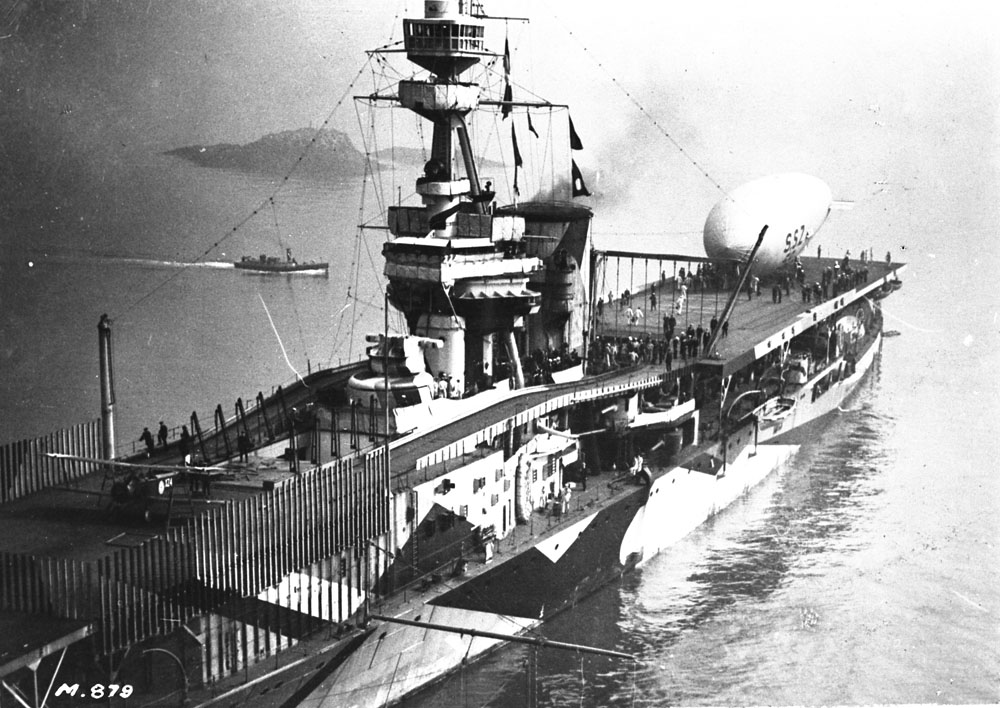

Dunning landing on Furious

But it was obviously a stopgap solution, as were plans to convert the large light cruiser Furious into a very fast semi-carrier by replacing her forward 18" gun with a flying-off deck and a hangar for 10 planes. Plans to add landing-on decks to various ships were discussed, although the first landing on a moving ship actually took place on Furious's flying-on deck when Edwin Dunning flew alongside the ship as she steamed at 26 kts into a 21 kt wind, resulting in a combined wind-over-deck slightly above the 45 kt landing speed of his Sopwith Pup. He was then able to sideslip in front of the superstructure and descend straight down onto the deck, where a party waited to secure his airplane. This procedure was dangerous for several reasons, most notably that the plane was essentially still flying on touchdown, making it extremely vulnerable to gusts. Five days after his first landing, Dunning was killed attempting to repeat the feat when a gust caught his aircraft on the verge of landing and blew it over the side.

Furious with a blimp on her landing-on deck

The obvious solution was to install a deck aft, and the aft 18" gun on Furious was quickly landed in favor of a way to recover airplanes, with tests beginning in March 1918. Unfortunately, while some wind tunnel tests had been run, the practical impact of the turbulence coming off the superstructure had been drastically underestimated, with one plane going into the safety barrier forward of the deck at 30 kts despite a 30-kt wind over deck measured forward. A few pilots did manage to land safely, but it was clear that this was not a practical option.

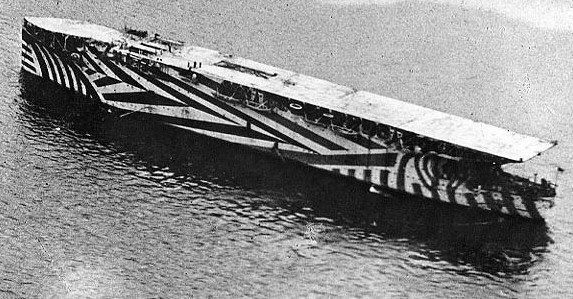

Argus

The turbulence problems on Furious forced a redesign of her successor, a hull laid down as a passenger liner that had been taken over by the Admiralty for conversion into the world's first true aircraft carrier, HMS Argus. Initially, she had been designed with a pair of islands joined by a bridge between the forward flying-off deck and aft landing deck, but these were removed and she was completed without any protrusions above the flight deck, the uptakes (exhaust) for the boilers being trunked aft. The flush deck, combined with careful detail design work,1 meant that putting a plane on deck was fairly straightforward, provided the ship was steaming into the wind. Stopping was also very straightforward, despite the lack of brakes on the planes of the day, as a 25-kt wind over deck would swiftly bring a draggy biplane to a halt without the need for any arresting gear. But then said biplane would be sitting in the middle of the deck, where a gust might easily flip it over the side. The result was what was known as "restraining gear", a series of ropes running fore and aft between two wooden ramps. The pilot would land aft of the restraining gear, then roll forward into it, allowing hooks on the undercarriage to snag the ropes and keep the plane stable until the handling party arrived.

A Sopwith Strutter about to go into the restraining gear aboard Argus

This system worked well enough in tests, but caused a number of headaches in operational use. First, planes couldn't be landed very fast, as getting one out of the gear required a fair bit of hassle, to say nothing of resetting the wooden boards that propped up the ropes between the ramps. And even discounting that, the plane needed to be struck down into the hangar before the next plane could land, resulting in a landing interval of about 5 minutes, and requiring planes to return with a fair bit of fuel, which in turn limited range. Second, it didn't give the pilot any indication that it had engaged, so if he mistakenly thought he'd missed and tried to go around, an accident was very likely. Third, even when it wasn't in use, it was still taking up that portion of the deck, which was effectively impassible to planes. And fourth, because the hooks were on a bar between the wheels, it couldn't be used by torpedo bombers, which planned to drop a torpedo through that space. This was considered acceptable, as torpedo bombers were big and heavy enough that they usually wouldn't be blown over the side before the handling party could reach them.

A Strutter taking off from Argus

This was a particular problem as the British began to investigate a mass torpedo bomber attack to damage the High Seas Fleet in port. Instead of needing to fly off an occasional plane to spot or shoot down a Zeppelin, they would need to get as many planes as possible in the air quickly. The method they used was fairly simple, and remained pretty much standard until the arrival of jets. Planes would be brought up from the hangar below the flight deck2 using an installed elevator, then taken aft by the handling party and readied for flight. Once several planes were "ranged" together, the engines would be warmed up and the first one would take off, followed by the others in sequence. The maximum size of a strike that could be flown off at once was set by the amount of deck available to park planes on aft of the first one to take off, which in turn had to be able to get airborne off the deck ahead of it. Because of the presence of the restraining gear, Argus was limited to only 5 torpedo bombers at a time, although this could have gone up for lighter aircraft which required less distance to take off.3

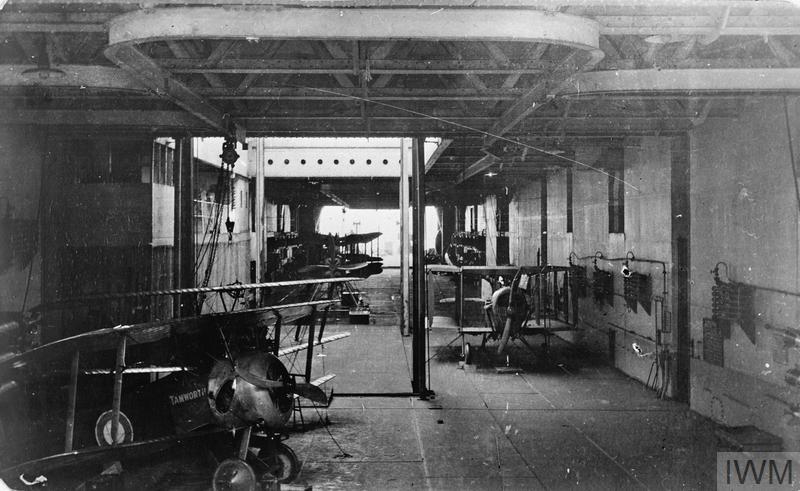

The hangar aboard Argus

Nor were all of the innovations aboard Argus on the deck. Underneath it was the biggest hangar ever fitted to a ship, 330' long and 48' wide, and serviced by two lifts. It was surrounded by workshops for all of the various specialties needed to keep the air group working, from carpenters and engine mechanics to tire fitters and instrument repair technicians. The danger of fire was very much in the mind of the designers, and the volatile aviation gasoline (avgas) was stored in 2-gallon cans in a special hold forward of the hangar with separate ventilation and water in the spaces around it. If the worst happened, three fireproof curtains would descend and subdivide the hangar, while extensive facilities were provided for putting the fire out.

In broad terms, Argus set the pattern for all carriers down to the present day, a testament to the work of her designers, but there was still a long way to go before carrier aircraft became the main striking arm of the fleet. We'll take a look at developments in the interwar years next time.

1 Wind tunnel tests showed that rounding down the aft end of the flight deck significantly improved airflow for landing. ⇑

2 The hangar was viewed as necessary because the planes of the day were exceptionally fragile and leaving them on deck would have exposed them to wind and wave. By WWII, planes had become much more durable, and a substantial portion of the air group has been kept on deck since then. ⇑

3 My sources are actually a bit unclear, and the size of the strike may have been set by the number of men available to handle the planes on deck. As they lacked brakes, each plane had to be held down and chocked until it was ready to fly. Also, there were issues with engines, which could take as much as 10 minutes to start, but would overheat if left running in still air for more than 2-3. Later carriers didn't have to deal with these problems. ⇑

Recent Comments