When one thinks of oceangoing tankers, the obvious cargo is oil, and oil tankers do indeed make up the bulk of liquid-cargo tonnage. But crude oil is far from the only liquid cargo that is transported across the world's oceans, and a surprisingly diverse and interesting fleet of specialized tankers is used to do so.

LPG carrier Victoria Kosan

The most common of these are carriers for various petroleum gases, which are transported in liquid form because this reduces the volume required by factors ranging from 230 to over 600. These products are usually divided into Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), mostly butane and propane, and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). LPG can generally be kept liquid at ambient temperature by reasonable pressures, or at ambient pressure at fairly reasonable temperatures. The first LPG carrier, launched in 1931, used pressure, as did most LPG vessels until around 1960, when refrigeration plants began to be more widely used. Today, the system depends on the exact operating economics, with smaller vessels favoring pressure.

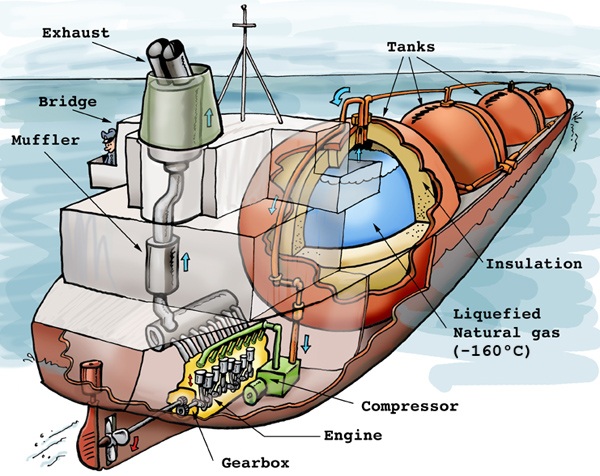

LNG carrier Galea

The advent of gas refrigeration also allowed LNG to be carried at sea, and it quickly grew to eclipse LPG on the world's oceans. Liquefying natural gas requires cooling it to the boiling point of its main component, methane, -162°C. Handling a cargo that is both cryogenic and highly flammable requires special care in design and operation, even though the work of liquefaction is done ashore. Special steels are required for the tanks, as normal steel is too brittle at the temperatures in question. Careful design work is needed to prevent damage from thermal contraction when the tanks are cooled before loading cargo. And loading is an involved process, with the tanks first filled with an inert gas to prevent an explosive atmosphere from developing, and then pre-cooled before the bulk of the LNG is brought aboard. When in operation, it is common to keep some LNG in the tanks after unloading to avoid having to repeat the procedure on every voyage.

A diagram of the spherical tank system

Two major solutions have been developed to the problems of integrating LNG tanks aboard ships. The more recognizable is the self-supporting system, composed of 4-5 insulated spherical tanks that generally protrude through the deck of the vessel, making LNG carriers of this type very recognizable. These are easy to design and build, but waste a great deal of space. The alternative is membrane tanks, which follow the vessel's hull, with specialized membranes to compensate for thermal contraction. These have gained popularity recently due to lower port fees, but require more insulation and greater care in design.

A membrane LNG tanker

Despite the efforts of engineers, some heat will leak into the tanks, boiling off a bit of the methane. For a long time, it was common to use this boiloff as fuel for the ship, either in a steam boiler or a gas turbine. This caused many headaches, including disputes over payment for the boiloff and tax questions. More recently, many ships have been fitted with plants to reliquefy the gas and return it to the tanks. On the whole, the LNG sector has seen rapid growth over the last few decades, as use of natural gas has spread.

CNG carrier Jayanti Baruna

Of course, all of the equipment to liquefy and handle natural gas is expensive, often taking a decade or more to pay for itself, and in recent years, shorter, lower-volume routes have seen a shift to Compressed Natural Gas (CNG). This is stored at over 250 times atmospheric pressure, although the density of the resulting product is still only about 40% of that of LNG. All gas carriers are inherently volume-limited rather than weight-limited,1 so a CNG carrier is able to carry less cargo, a factor offset in many cases by the relatively low infrastructure costs.

Piping on the chemical tanker Ginga Falcon

While tankers for petroleum fuels make up the bulk of the fluid-carrying fleet, they are joined by an array of ships carrying out more specialized tasks. The oldest and most prominent are the chemical tankers. Initially, this was merely a job handled by oil tankers when loads of chemicals like caustic soda and sulfuric acid had to be moved to and from refineries, but in the 1930s, specialized tankers began to be developed for the job. After WWII, the trade grew rapidly, with new cargoes, both liquid and gas, taking to the seas and bringing with them specialized handling requirements. Some were very flammable or even ignited on contact with air, and had to have their tanks filled with inert gases. Others needed to be kept under pressure or at specific temperatures. A few were highly toxic, and had to be kept at a distance from crew quarters and monitored for leaks, and others would react on contact with the steel of a ship's hull. Major cargoes today include ammonia, used to produce fertilizer, ethylene, a feedstock for plastics, and various industrial acids. A modern chemical tanker has numerous cargo tanks and a complicated piping system to allow it to safely handle dangerous cargoes without the risk of cross-contamination, as the standard assays for chemicals require purity levels in the parts per million. Most run standardized trades with the same chemical on each run, as the difficulty of cleaning tanks to the required standard makes switching cargoes very difficult.

Sulphur Genesis

A few cargoes deserve special mention for their unique requirements. A weird mirror of the problems of LNG carriers can be found in ships designed to carry molten sulfur. This has to be held between 138 and 155 °C to keep it in the proper state, achieved by the fitting of steam heating coils. Even piping systems are fitted with steam jackets to keep the sulfur from becoming viscous and plugging up the system. To make things worse, the cargo is corrosive, and could potentially explode if was exposed to air. Phosphoric acid also has to be kept heated, and it tends to form a sludge on the bottom of the tank, which has to be broken up before it is pumped off the ship. This is often done by using a jet of the acid itself. Asphalt/bitumen is another cargo that has to be heated for handling, with temperatures ranging from 180°C on up. Double tanks are used, and pre-heated for 12 hours or more before cargo loading to prevent structural problems, and the crew are issued wooden clogs to protect their shoes from the hot decks.

Matadi Palm, carrier of palm oil

Another trade closely related to that in chemicals is that in edible oils and fats. While the ships are usually different, the purity standards required for cargoes like palm oil and tallow are very similar to those for industrial chemicals, and they are handled in the same manner. Molasses is another major edible liquid cargo, although it is normally destined for animal feed, a use that requires lower standards in handling. Bulk carriage of molasses dates back as far as 1912, but it was often used as an alternate cargo for oil tankers until the 1960s, when growing tankers and changes in pump design made it the domain of specialized carriers. Heating systems are needed for discharge, although unlike other cargoes, molasses does not have to be shipped hot.

MV Miranda Guinness, the last of the Guinness tankers

The oldest trade of liquids at sea is probably wine, with many 3,000-year-old shipwrecks yielding amphorae containing wine residue. Obviously, they were handled as break-bulk cargo, and even today, a great deal of alcohol travels already packaged.2 But for cheaper products, it is vital to keep distribution costs to a minimum, and a handful of companies in Europe built tankers for the transport of wine and beer. These were generally very small, only a few hundred to a few thousand tons, and fitted with stainless steel tanks and equipment to keep the cargo cool. The wine tankers were usually owned by shipping companies, while the beer companies usually owned their own distribution vessels, most notably Guinness, who operated a fleet of beer tankers from 1913 to 1993. Not all beverages transported by sea are alcoholic, either. The growing appetite for fruit juices in the 1980s saw several tankers built to carry orange juice concentrate from Brazil to markets in the US and Europe. These were fitted to keep the concentrate at -7°C, and all of the tanks and piping was carefully designed to avoid contaminating the cargo.

Orange juice tanker Orange Blossom 2

The efficiency of dedicated tankers has seen dozens of cargoes carried by specialized ships across the world's oceans. Some types have dozens or hundreds of ships in service, while others have only a handful. And this diversity isn't limited to liquid cargoes, either. We'll take a look at the specialized cargo ships that populate the world's oceans next time.

1 LNG has a density around 426 kg/m3, while seawater is 1025 kg/m3, so the cargo/ship weight ratio is much smaller than for something like a bulk carrier. ⇑

2 Interestingly, the whiskey industry in particular was an early adopter of containerization because they had always had serious losses on the docks. ⇑

Comments

Bean,

Any idea by how much the U.S. is increasing LNG shipping capacity in light of trying to offset Germany's Nord Stream 2 plans? Was the capacity already existing or is it something that is being gradually built up?

I know this is a hot political topic and even this past week the U.S. has announced more sanctions on the project (as per Deutsche Welle https://m.dw.com/en/nord-stream-2-germany-unhappy-with-new-us-sanctions/a-53805296) so I would imagine this is a moving target.

I know one of the European ports (was it Rotterdam?) has made significant investiture in processing capacity with the goal of being able to accept, and then distribute, LNG shipments, but Nord Stream 2 is projected at 55 billion cubic meters per year so that seems a lot if we are pressing to be an alternate supplier for Germany and Europe.

Of course the U.S. fracking industry had been knocked back recently so that probably will effect shipping and demand figures.

I don't really know about any of that, unfortunately. I write these looking primarily at history and the general technical development of these ships. My best source is from 1992, and the exact details of what is going where has changes a bit since then.

No worries Bean. This issue with sanctions and the Nord Stream 2 has been occupying the striped pants set at the State Department for some time and I was curious if we actually had enough LNG capacity to ensure a high volume of uninterrupted supply to Northwest and Central Europe.

Your description of the care that needs to go into the design of these vessels and the handling of this type of cargo made we realize that one simply cannot convert existing ships in short order.

NS 2 only has another 160Km to go but it is going to be interesting to see when it if finished as the U.S. is leaning hard on what firms it can that are involved with the project.

It just blows my mind that people have built entire ships specifically for transporting orange juice in bulk. Soothly we live in mighty years*.

I've previously been amazed at the amount of orange juice transported by rail. I live in the DC area, and around a quarter of the cargo trains I see passing through are orange juice (or possibly just oranges?) headed north. I can only assume it's because as opposed to other beverages the production is so geographically localized.

I do see a lot of milk tanker trucks getting around. Never noticed orange juice though.

I used to live overlooking (at short range - we ran the windowbox AC 24x7x365 at least in fan mode for white noise to drown out the noise) a Conrail line into NYC. The vast majority of observed traffic was orange juice inbound and garbage outbound.

And one Barnum and Bailey train

Was it actually orange juice, or was it orange juice-branded reefer cars? Because even for NYC, that seems like a lot of juice.

They were Tropicana-branded reefer cars, no idea what was actually in them, but there are a lot.

Looking into it some more, apparently for some time there was whole separate train. The scale of commodities can be so bizarre at times.

@bean

whoops thought you were replying to me. Sorry @Ian