While the container ship is perhaps the public face of maritime trade today, they make up only about 13% of the world's shipping fleet.1 For all of the TVs, car parts and clothes that cross the oceans in containers, oceanic transport is dominated by bulk cargoes like coal, iron ore, oil and grain. These cargoes are measured by weight and handled entirely differently from containerized cargoes. While liquid cargoes definitely deserve their own discussion, today we'll focus on the solid bulk carrier, which makes up 43% of the world's shipping fleet.

Bulk carrier GH Fortune heads to sea

Until the end of the 19th century, oceanic bulk cargo was largely carried by sailing ships, which were cheaper than steamships until the development of the triple expansion engine. Coastal trades made more use of steam, with early examples like the John Bowes entering service from the middle of the century, particularly in the coal trade. But even then, bulk cargoes were often bagged and loaded and unloaded by hand, much as contemporary break-bulk cargo was. These were some of the staples of the tramp trade, which saw vessels chartered for specific loads of cargo, usually only one way, and their owners had to string together a series of contracts to make a profit. While ore and coal were quickly moved to specialized bulk carriers, other bulk cargoes remained aboard tramps well into the second half of the 20th century. Grain, the flow of which greatly depended on harvests worldwide, was a common tramp cargo, as were smaller-volume goods like sugar, forest products, and scrap metal.

Lake freighter Edmund Fitzgerald, lost in a storm in 1975 and immortalized in song

Even as late as 1937, only 25 million tons of ore was transported on oceanic routes, so the demand for specialized bulk carriers was small. Instead, the hotbed of bulk shipping was the North American Great Lakes, which had seen three times as much ore shipped to the great industrial cities like Detroit and Pittsburgh a decade earlier, not to mention other bulk goods like coal and limestone. Shippers were driven to experiment with specialized vessels much earlier, not only by the volume of the trade but also because of the lack of general-purpose vessels as competition. These had their bridge forward and engines aft, leaving the entire midsection of the vessel for the cargo, stored in holds under large hatches which could be loaded via chutes and unloaded by shoreside grabs.

Bulk Carrier Shinano unloads one of her holds with her onboard cranes

The next step was to make ships able to unload without the aid of shoreside equipment. The first versions simply had slopes in the bottom of the hold to concentrate the cargo in a specific spot, where it would be scooped out by an onboard crane. Later vessels had conveyors running under the holds which would carry the cargo to an onboard elevator, which would then discharge it into a chute. These both reduced the time required to discharge, but more importantly saved a great deal of manpower, which was becoming increasingly costly. A few seagoing bulk carriers of this type were built starting around 1900, primarily for shipping Swedish iron ore to the rest of Europe, but the bulk carrier as a general type didn't really take off until after WWII.

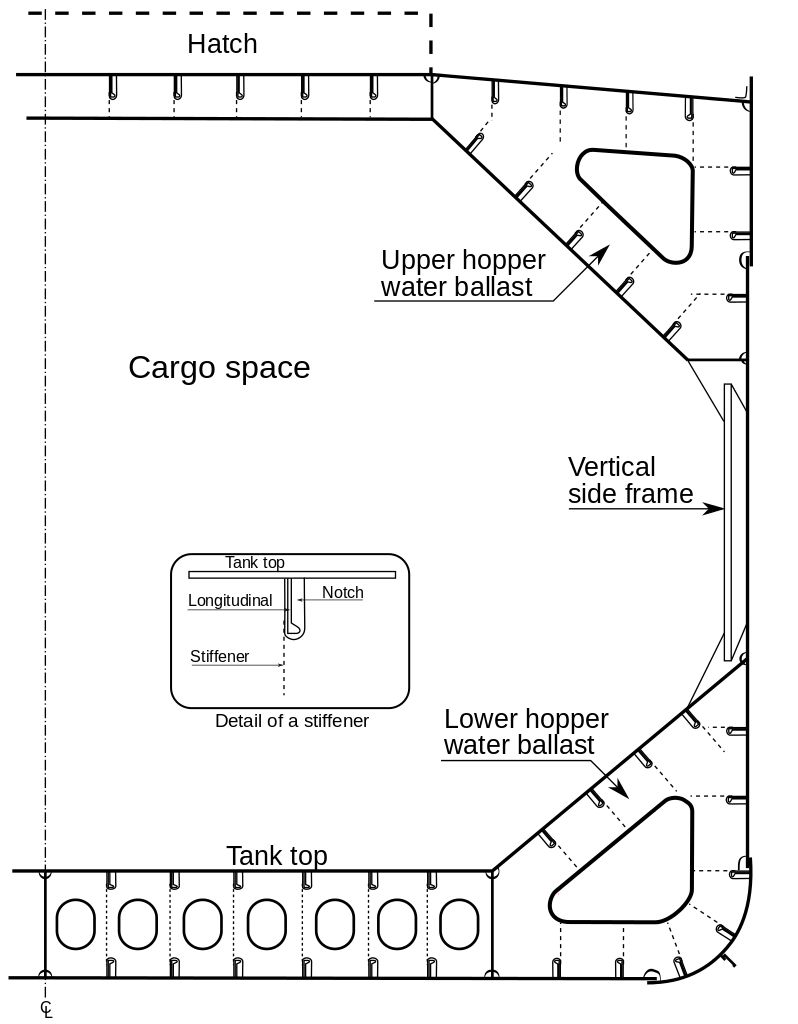

A midship section of a typical bulk carrier

The modern bulk carrier has a single deck over the cargo holds, shaped so that the cargo doesn't end up in mounds no matter how it's poured in. Holds are often fitted with baffles to keep the cargo from shifting, which can greatly reduce the stability of the ship, even to the point of causing it to capsize. Under and beside the holds are ballast tanks, filled with water to maintain stability and good roll characteristics when the ship is making voyages "in ballast", without a paying cargo onboard. These voyages are common for the largest bulk carriers, which are usually operated on long-term contracts for a specific route, such as carrying coal and iron ore from producing countries like Australia to industrial nations like Japan and China.

Sister ships Vale Sohar and Vale Rio de Janeiro provide a graphic demonstration of the change in draft between unloaded and loaded bulk carriers

Modern bulk carriers come in a wide range of sizes. Numerically, the most common categories are the handysize and handymax ships, which can carry up to 60,000 tons of cargo. These vessels are almost always fitted with cranes to allow them to offload themselves in smaller ports, and carry everything from coal and iron ore to grain, cement, phosphate rock, logs, sugar, scrap metal, bauxite, salt, gravel, tapioca, potash, gypsum and various non-ferrous ores. The largest bulk carriers are capable of carrying three times as much, but tend to be specialized in a specific trade, and their size is determined by the ports they have to enter in that trade. The largest bulk carriers, known as capesize, are too big for the Suez and Panama Canals, and have to navigate around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn respectively, paying for their longer voyages with the lowest costs per ton-mile of any transportation method known to man. In 2011, the 65-strong Valemax class became the first bulkers to break the 400,000 ton mark, a record they still hold today.

OBO carrier Maya with her holds loaded with soybeans, showing the piping for her second role as an oil carrier

One of the major problems with bulk carriers running predictable routes is that their cargoes flow only in one direction, forcing them to return in ballast to pick up another load. One potential solution was the ore/bulk/oil (OBO) carrier, developed during the 1950s. Early versions were simply bulk carriers with oversized ballast tanks, filled with oil when that was to be carried and left empty when dense ores were onboard. The problem was that these ships were not suited to less dense cargoes like grain, and in the 1960s, shippers began to build ships that could carry oil and bulk cargoes in the same holds, with specialized cleaning systems and oil-tight hatch covers. Unfortunately, it was difficult to make the ships profitable when dealing with the differing demands of the oil and dry bulk markets, and the OBO faded from the world's oceans.

Capesize2 bulk carrier Geneco Titus passes the Suez Canal Bridge

The bulk carrier forms a vital link in the world's industrial economy, carrying a significant fraction of the world's raw materials more cheaply than any other method. But one form of bulk cargo, the most important numerically, has been ignored so far. Next time, I'll take a look at the vital oil tanker.

1 Measured by deadweight tonnage, numbers taken from here. ⇑

2 Capesize is a rather inconsistent term. In some cases, it means "too big for either major canal", while in others, it just means "too big for Panama". Recent deepenings of the Suez Canal have confused the matter further. ⇑

Comments

Do you have some sense of what fraction of cape-size vessels use the capes and which just stay in their home ocean?

Not really. Most of this post was based on Conway's The Shipping Revolution, which is a great book, but is as old as I am. Market patterns have changed significantly since then. I don't know of much traffic around Cape Horn, but the Cape of Good Hope sees quite a bit, as does the Suez route. (Suez, of course, can take some Capesize vessels, depending on what definition you use.)

In fact, bulk cargo- nitrates from Chile, then grain from Australia- was what the last commercial sailing cargo ships carried. The ships from Australia continued sailing until WW2. Apparently part of what kept them competitive was the fact that a sailing ship costs much less to have sitting in harbour than a steamship does, so they could afford to wait for months as grain was brought from different farms. Another important factor was that various countries required merchant marine cadets to get a certain amount of experience on a sailing ship to get their licence, so some of the crew were cadets who would work for low or no pay or even pay to be there!

The Last Grain Race, by Eric Newby, is a superbly written account of his voyage to Australia and back as an apprentice on Moshulu in 1938.

No, not respectively. Suez and Cape of Good Hope are in Africa, while Panama and Cape Horn are in South America.

@AlphaGamma

Interesting. That wasn't an aspect I looked into because this was intended to be high-level, but that makes sense. I'm amazed countries kept sail requirements that long.

@Aula

I'm usually capable of telling those apart, but apparently failed this time. Fixed.

Whenever there is discussion of 20th century sailing ships, I am contractually obligated to mention one of my favorite ships, SMS Seeadler, the sail powered merchant raider used by the germans in ww1 that sank 30,000 tons of shipping.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMSSeeadler(1888)