Southeast Asia has long been one of the world's maritime crossroads. The Strait of Malacca, connecting the Indian and Pacific Oceans, has been important to sailors carrying goods between East Asia, India and Europe since Antiquity, and continues to be vital to international trade today. Southeast Asia is also dotted with islands, which has long incentivized its inhabitants to participate in maritime commerce. Unfortunately, all too many of them decided the best way to participate was as pirates, a problem that troubles the region even today.

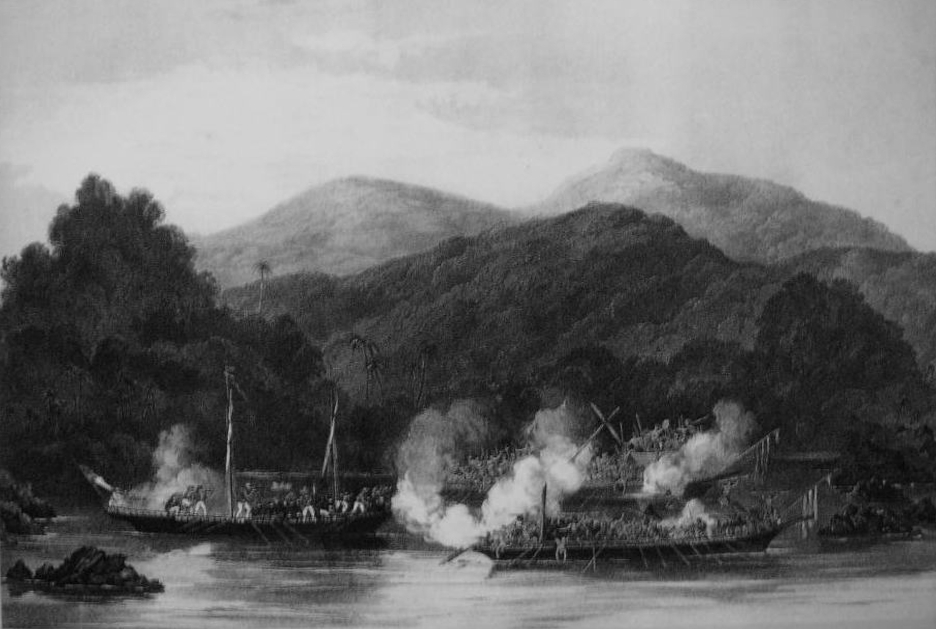

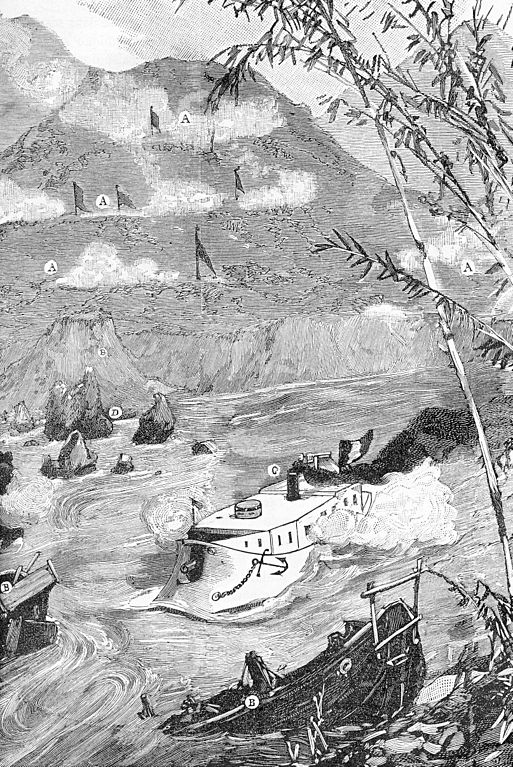

A battle with pirates off Borneo

Many of these pirates chose to base themselves up rivers, making it exceptionally difficult for official naval forces to track them down and destroy them. The novel Flashman's Lady contains a meticulously-researched account of one such expedition in Borneo, led by James Brooke, the White Rajah of Sarawak.1 But while fighting piracy on rivers continues to this day, Southeast Asia is far better known for the French and American riverine campaigns in Indochina, particularly the Mekong River and its delta.2

Saigon falls to the French and Spanish

This pattern was set by the first efforts of the French to claim territory in what is now Vietnam. In 1858, a joint Franco-Spanish force was dispatched in an attempt to end persecution of Catholic missionaries, an effort which later morphed into a war of conquest. To cut food supplies to the Vietnamese army, the French decided to take Saigon via an expedition up the Mekong. The forts guarding Saigon were destroyed by the expedition's warships, and Saigon itself soon fell. The Second Opium War distracted the French, and they left only a small force in Saigon, which held out for two years, supplied from the river. The Anglo-French victory over China in 1860 freed ships and men for Indochina, who quickly lifted the siege of Saigon, and then proceeded to seize Cochinchina,3 often using gunboats for both fire support and mobility.

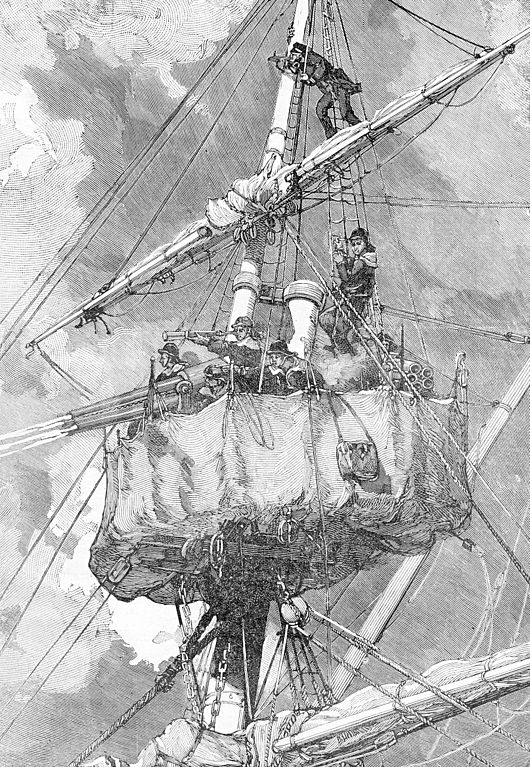

A Hotchkiss revolver cannon on the masthead of the gunboat Pluvier engages the enemy at Nam Dinh

By 1883, the French had grown dissatisfied with Cochinchina, and desired to expand north, into the rest of what is now Vietnam. The Red River offered a potential path into the Chinese interior, bypassing the Yangtze, but the Vietnamese continued to interfere with French trade in Tonkin, what is now northern Vietnam. A French naval officer, Henri Riviere, was sent to investigate, and he promptly acted to force the government's hand, securing a position near Hanoi and then capturing the city of Nam Dinh with a force outnumbered 11 to 1 while suffering minimal casualties thanks to the firepower of his gunboats. A gunboat also helped beat off a simultaneous attack on the garrison at Hanoi, whose defenders were outnumbered by an even greater margin. Unfortunately, Riviere was then drawn into an ambush and killed, leaving France furious and drawing in forces for a full-scale war.

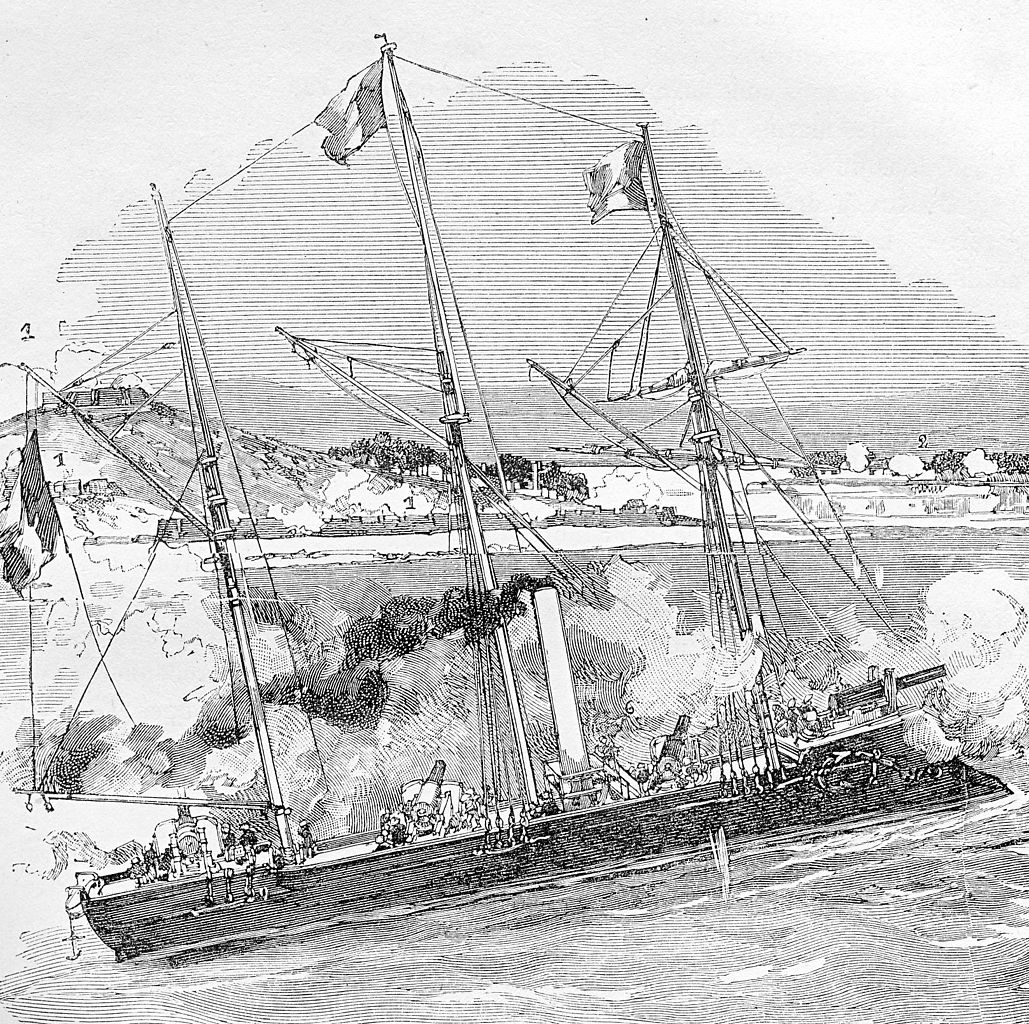

Gunboat Vipere attacking the forts near Hue

These forces first struck at the forts guarding the Perfume River, which flows through the Vietnamese capital of Hue. The French captured the forts with the aid of a pair of gunboats that forced their way up the river, and with Hue left exposed to attack, the Vietnamese quickly negotiated a treaty effectively making all of Vietnam a French colony. But the Chinese, who had long been the overlords of Vietnam, were not ready to give up so easily, and the fighting in Tonkin continued, with gunboats of the newly-formed Tonkin Flotilla playing key roles in many battles throughout the Red River Delta, providing both firepower and mobility and allowing the French to bypass enemy defenses by sea.

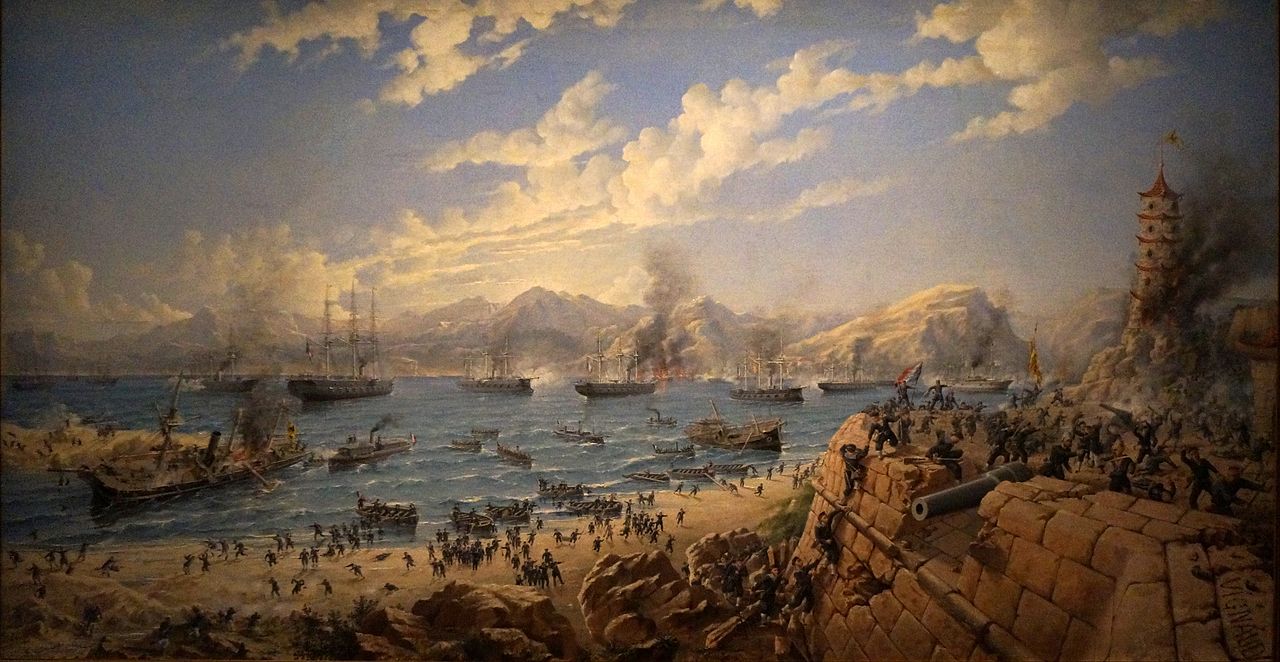

The French attack on Foochow

By 1884, tensions between France and China had reached the breaking point thanks to the undeclared war in Tonkin, and more forces were dispatched to the Far East under Admiral Amedee Courbet. He was sent to threaten Foochow Arsenal on the Min River near Fuzhou,4 the main base for the Chinese Fujian Fleet.5 Finally, on August 22nd, the order came through, and Courbet gave appropriate notification of his intent to attack the next day.6 The Chinese took no action, and at 2 PM, when the tide had swung the sterns of the anchored Chinese vessels towards his force, he launched the attack.

The successful spar torpedo attack on Yangwu

The first act was remarkable for being one of the few successful uses of the spar torpedo, a weapon consisting of an explosive charge attached to a boom on the front of a boat. Courbet's two torpedo boats attacked the Chinese corvette Yangwu and gunboat Fuxing, successfully sinking Yangwu. Most of the other Chinese ships were destroyed by fire from Courbet's heavier ships, joined by the ironclad Triomphante, who arrived just as the fighting started. Only two Chinese ships survived, both having fled in the opening moments of the battle. The next day, Courbet's ships bombarded Foochow Arsenal, although his heaviest ships drew too much water to participate, limiting his effectiveness. He then turned down the Min River, destroying the Chinese forts guarding it with ease as they were placed to stop ships heading upriver. Later, Courbet attempted to starve China by blockading rice transport at the mouth of the Yangtze, but overland and canal transport made it relatively ineffective.

Revolver in action

To avenge their defeat at Foochow, the Chinese sent an army into Tonkin, planning to eject the French from that territory. Unfortunately, it gave away its presence by ambushing a pair of gunboats, and the French quickly responded. The Chinese had divided their force into three separate detachments, and the French made use of the mobility provided by their gunboats to defeat each of them in detail. Gunboats also proved vital to the defense of Tuyen Quang. Even after supply runs were stopped, the gunboat Mitrailleuse remained on station during the three-month siege, threatening the Chinese flanks along the Clear River. Gunboats also carried the relief force partway to its destination, but low water prevented them from participating in the fiercely-fought battle at Hoa Moc, despite the best efforts of the gunboat crews to haul their ships along the riverbed.

Gunboat Eclair

The last few months of the war saw the fighting move inland, away from the navigable rivers, but in April 1885, a peace treaty was signed. All of modern Vietnam was now under French control, although it took a number of years for that to be fully realized. Gunboats also participated in the pacification campaign, and served in Indochina throughout its life as a French colony. After WWII, France reasserted control over the region, and riverine forces would again play an important part in their efforts to maintain their rule. We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 I know it looks weird to cite a novel for something like this, but the author, George MacDonald Fraser, conducted a staggering amount of research for each of the Flashman books, and the incidents are usually drawn directly from history except for the actions of the titular character. ⇑

2 As usual, I have essentially no sources for riverine warfare in the area before the 19th century, so I'm not going to cover it.c ⇑

3 Now the very southernmost part of Vietnam. ⇑

4 Technically, this probably should have been part of the posts focusing on China rather than Southeast Asia, but it's tied into the history of Vietnam, so I placed it here. ⇑

5 As I've mentioned before, Qing China had a rather odd system with 4 separate regional fleets, each mostly independent of the others. ⇑

6 Yes, this really happened, weird as is sounds to modern ears. A number of neutral warships had observed the action, and their captains sent congratulations to Courbet on his professionalism throughout. The 1800s were a different time. ⇑

Comments

One could teach a perfectly serviceable, and very entertaining, class on 19th-century history using the Flashman Papers as the primary text. The great objective would be to do this during a wanderjahr, reading each book on location.

What's weird to me is that the Chinese took no move to fortify their position or launch a preemptive strike upon receiving Courbet's message. Passages about late Qing military (especially naval) decisions always seem kind of stupid when taken out of context, but there's got to be some sort of thought process, even if their mental model doesn't make much sense anymore.

One of the factors in late Qing military decision-making was the extreme reluctance of many commanders to ask for reinforcements, because of the loss-of-reputation that this would entail. As a result, we see time and again that Qing military commanders would repeatedly assure the central government that matters were well in hand, victory was inevitable, the barbarians will soon feel the might of the Chinese empire, etc etc. And then, after the battle was fought, oops! There was some totally "unforeseeable" circumstance that allowed the barbarians to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Those darned barbarians! We'll get 'em next time!

Sure, the desire to save face is strong in Confucian cultures, but c'mon. Losing a battle has got to destroy a career and reputation far faster than just asking for backup. Plus, there ought to have been some pushback from the central government stressing the importance of actually winning once in a while.

My knowledge of the late Qing culture comes pretty much exclusively from Flashman and the Dragon, but they were insanely, outrageously self-centered. It took an Anglo-French army pretty much laying siege to Peking to get their attention in the Second Opium War, and despite military defeats, they tortured a bunch of captives, leading to the destruction of the Summer Palace. They really did think they were from the most important country, and that nobody else mattered.

Like most, I too only know about 19th century Chinese military what I read in the Flashman books.

But cultural and political inability to admit anything other than glowing fantasies about how the war would be won any day now is hardly unknown across a range of different times and nations.

From WWII Japanese to Napoleon's march on Moscow, there is a common failure mode of anything other than an amazing victory against all odds will result in me losing my career, and maybe my head, so I might as well just roll the dice.

I'm Doing Reaserch On French Riverine Monitors (Built From U.S.-Made LCM Mk.6 Type Landing Craft,) From The Vietnam War For A Model Building Project. I Could REALLY Use Measurements And Dimensions For At Least A Few Basic Types Of These Craft Since Very Few Were Constructed To A Standardized Design.Could You Help?

---------------Matthew J. Rosa (mattrosa1961@gmail.com)