In 1979, the Shah of Iran was overthrown, bringing a new government, headed by Ayatollah Khomeini, into power. Khomeini's vision of an Islamic state was very different than what had been there before, and the country was in chaos even before students seized the US embassy and kept its diplomats hostage for 444 days. Saddam Hussein, who had recently seized control of Iran's neighbor Iraq, was irritated by Khomeini's description of him as a "puppet of Satan", coupled with calls for the majority Shia population of Iraq to overthrow the Sunni-dominated government. There was also the question of who should control the Shatt al-Arab, the river formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates that serves as an important outlet from Iraq to the sea. In 1975, Saddam had signed a treaty drawing the boundary at the center of the river, but in September 1980, he tore that up, reasserting Iraq's traditional claim to the entire river and ordering his forces into an Iran that he expected would be unable to effectively resist due to the tumult of the revolution.

In this, he would be gravely disappointed. Although his forces made reasonable gains early on, Saddam was not a particularly good commander and the war unified the Iranian people behind the new government. By the end of 1980, the Iraqi offensive had ground to a halt, and after staying stalemated through 1981, the Iranian counteroffensive in 1982 drove Iraq back to its start lines, often making use of human wave attacks, massed charges driven by religious fervor that were sometimes used to clear minefields in the fastest and highest-casualty way possible. But there was also enough technical skill left in Iran to conduct operations against the Iraqi Navy and generally make the Iraqi coastline unsafe, slashing oil revenues. After a key pipeline through Syria was closed, the Iraqi war effort was sustained only by loans from Kuwait and Saudi Arabia,1 as well as material and technical support from both sides of the Cold War, neither of which was eager to see Khomeini's version of Islam spread.

Tankers load oil at Kharg Island

Iraq had been nearly exhausted by the initial offensive, and spent the next few years effectively on the defensive. The Iraqi Air Force, which had been comprehensively defeated at the start of the war, was finally becoming marginally competent, while its Iranian counterpart withered due to lack of spare parts and ongoing purges of personnel left over from the days of the Shah. In 1984, these factors combined to allow the Iraqis to attack Iranian oil exports, which made up the vast majority of Iranian foreign exchange. This included both bombing raids on the main Iranian oil complex at Kharg Island in the northern part of the Arabian Gulf and the use of French-provided Exocet missiles2 against tankers carrying Iranian crude. Unfortunately, the Exocet was designed to deal with small warships, which tend to be packed with important stuff, and so a typical hit on a supertanker would do little more than some damage to the plating.3 The Exocet's radar seeker was also quite primitive, which meant that it was easy to decoy, and the Iranians made extensive use of towed radar reflectors, but it also meant that the missile was likely to go for the superstructure on a loaded tanker, sparing the oil but greatly increasing the risk to the crew.

The initial Iranian response was to threaten the closure of the Strait of Hormuz, at the mouth of the Gulf, but the United States made it very clear that this would not be acceptable, so the Iranians settled for building new ports further south, where oil would be shuttled using dedicated tankers kept close inshore and protected by the Iranian military and shooting at the tankers of Iraq's backers, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Even that didn't last long, as Khomeini had decided that it would be better for Iran to stop antagonizing the entire rest of the world, and pumping missiles into neutral shipping was a bad way to go about that.

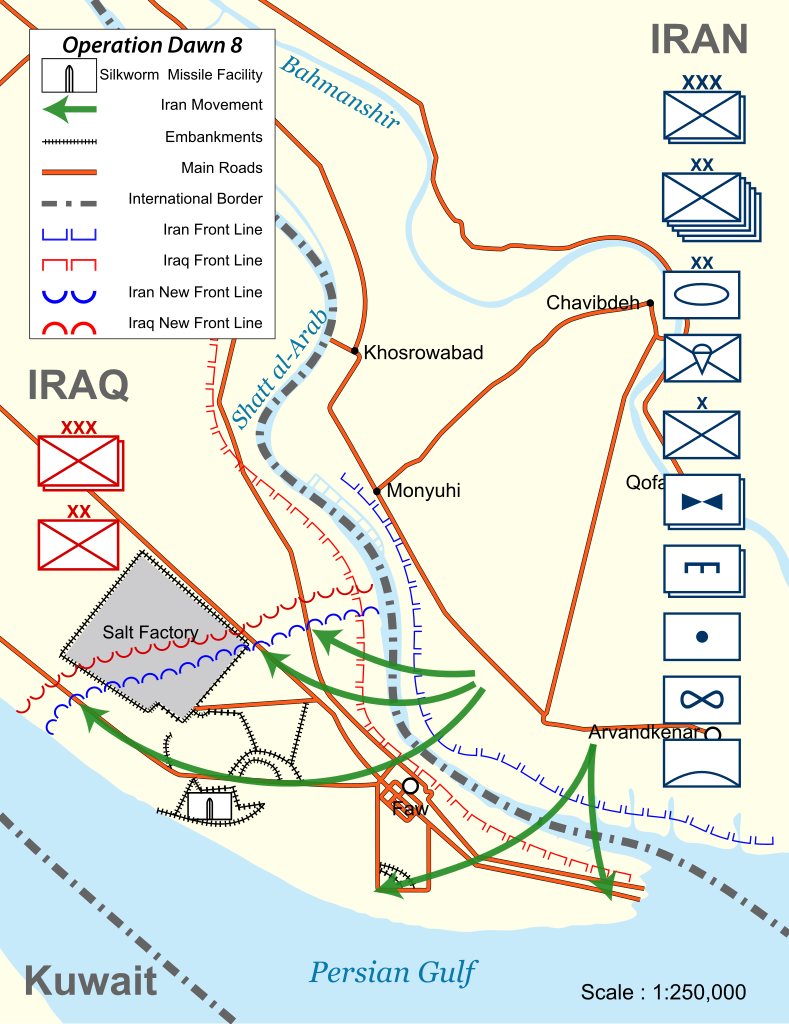

The Iranian attack across the Shatt al-Arab

Throughout 1985, Iran left the tankers pretty much alone, while Iraq restricted its strikes to tankers in Iranian waters carrying Iranian oil. Instead, the two sides spent much of the time sending bombs and Scuds to each other's cities. Despite this, Saddam continued to enjoy broad international support, at least to the extent required to make sure he didn't lose.4 That seemed closer in February 1986, when the Iranians launched an amphibious attack across the Shatt al-Arab, capturing the only bit of Iraq that actually touched the Gulf. This was particularly concerning to Kuwait, which now had Iranian troops practically on its border and Iran was not slow to remind them of that fact. Almost as worrying was Iran's purchase of Chinese Silkworm missiles, which not only had warheads six times the size of Iraq's Exocets but were also being emplaced in the newly-captured territory. And Iran had begun to intensify operations in the Gulf, regularly sending ships out to inspect merchant vessels passing through the Strait of Hormuz, and inspections and seizures of ships of the major powers occasionally saw the intervention of their warships in the area.

An Iranian Silkworm takes to the air

This finally prompted Kuwait to try to bring the superpowers into the conflict in hopes that they could end the war. Their chosen method was devious in its simplicity. Kuwait operated a fleet of oil tankers for its national oil company, and it put in requests to both the US and USSR that the vessels be reflagged under their national colors, which would allow the navies in question to protect them. Initially, the US was reluctant, but the Soviets, seeing an opportunity to gain a foothold in the Gulf, readily agreed, and Reagan felt he had no choice but to block them by taking all 11 of the tankers, signalling American commitment to a region where the nation's prestige had been badly hurt by the overthrow of the Shah, the 1983 Lebanon fiasco and the recently-revealed Iran-Contra scandal. The official reason given when the policy was announced in March 1987 was more high-minded, with the reflagging cast as an extension of the traditional US support for Freedom of Navigation. Worries about oil prices probably played very little part, as there was a glut of oil on the market, with prices falling almost two-thirds in 1986.

But the stakes would be dramatically raised in May, even before the first of the tankers was reflagged, when a mistake by an Iraqi pilot would kill 37 Americans and bring the USN fully into the fight against... Iran? We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 Later, an attempt to aggressively renegotiate the loans from Kuwait would bring Saddam into more direct conflict with the US. ⇑

2 To tide the Iraqis over until the Mirage F1s they had ordered were delivered, the French leased the Iraqis Super Etendards, which you might remember from elsewhere. ⇑

3 In some cases, the repair cost was less than the cost of the Exocet. ⇑

4 Henry Kissinger probably summed up international opinion best when he quipped "It's a pity they can't both lose", but an Iranian victory was both more possible and seen as a worse outcome. ⇑

Comments

Concerning recent discussion, I think the first few years of this war demonstrate that the Iranian air force was competent, then. They managed to keep a useful number of modern combat aircraft in action, despite 1. a self-imposed decapitation of the senior leadership by the revolution and 2. no access to US technical support, having to solve all problems themselves. Not possible without enough competent people and a general attitude "What does this bit do? I don't know, let's figure it out" rather than "The plane will fly if Allah wills it so".

(Yes I know about Iran-Contra. Getting spare parts that fell off the back of truck is not the same as, for example the RAAF here in Australia, having direct access to Northrop Grumman / Lockheed if things get tricky.)

Why is the Gulf Perisian in parts of the article and Arabian in others?

Because I'm trying to standardize on Arabian (mostly because this annoys Iran) and failing.

Ok, this might be a really really stupid question, but I know next to nothing about the professional application of violence to ocean vessels

If I wanted a destroyer's worth of armaments, electronic warfare things, whatever, and instead of putting it on a destroyer, I put it in the middle of a giant supertanker (somehow), would that make it basically invulnerable to damage? Obviously this would be ridiculous, extremely expensive, and maybe physically impossible (eg how do you fire cannons that are inside of the ship, without blowing holes in the ship). But, my question is more like, does ship armor work that way?

@techanon: one way to think about this is that being so big, supertankers have lots of space, which means there's lots of places that can take damage with no impact to the mission of carrying bulk fuel, at least for the weapons the Iraqis and Iranians had available. Additionally, if they are carrying crude oil, they have basically unlimited reserve buoyancy (because oil floats, of course). So it's hard for pure warheads using explosive power to destroy tankers, and even mines were of limited value (as we presumably will see). But (I assume bean will get here, but spoiller anyway), but think it was Zatarain in his book who noted that the Iranians figured out the Standard SM-1 launched in surface mode works great against tankers because it hits at a flat angle and usually still with a mostly full load of fuel aboard, setting them on fire. Crude doesn't burn easily, but if you get it going, doesn't stop. Modern heavyweight torpedoes probably work pretty well, too. I assume there's modeling on this somewhere.

The big issue with the armed merchantmen idea is that it's going to be very slow and easy to find, and also modern electronics don't handle shock well anyway, so one or two hits is going to mean the ship might be fine but the gear won't work anyway.

Hi @techanon, ship armour did in the past work in a similar way.

Two basic ways to inflict violence on a ship: you can ""mission kill" it, by damaging the Things That Do Stuff so it can't do whatever mission it was supposed to. Knock out the radar, can't see targets far away. Knock out the missiles and guns, can see the target but not shoot it. And so on.

Other way is just to sink it, by letting the water in until it no longer floats. This also mission kills them.

For battleships this led to the "citadel" or "all or nothing" design. If you put armour plate on everything, you have a humungous battleship that has, say, 16" armour plate protecting the ship supply of soap. So instead you pick out the bits you really want to keep working for the mission; engines, guns, ammo; and put heavy armour around those.

The enemy can then shoot as many holes as they like in the rest of the ship provided you have enough reserve buoyancy. The ship designer needs to make sure that no matter how much water comes in outside the heavily armoured citadel, it's not enough water to sink the ship anyway. (It would be really embarrassing to have your battleship sink after some destroyer poked holes in it with a 4" gun, despite all the big guns and engines being untouched and fully operational.) So the armoured citadel may have to be larger than strictly necessary.

The British navy in WW1 and WW2 used monitors, which are closer to the "tanker" approach in relying more on volume to protect a single battleship gun. Very hard to sink, but it would still take just one hit to mission kill them. And because of their size and shape they were very very very slow.

@techanon

It's a reasonable question, and one the USN has actually looked at a little bit. And yes, it would make it much less likely to be damaged, although there are some weapons (heavy torpedoes most prominently) that it wouldn't really protect against. Not to mention shock, although I suspect that could be mitigated if you had that much displacement to play with. The other issues are that it would be slow, and that things like docking facilities would be a problem when you tried to replace a 10,000 ton ship with a 100,000 ton ship.

I would say no, but that's mostly a question of how general we want to get. The basic point of armor is (mostly) that it keeps things out entirely, while the tanker is invulnerable because it isn't full of important stuff and crude oil is pretty good at dampening most impacts. One source said "like firing a rifle bullet into mud". If you want more details on armor and other things that can kill ships, look at the "Protection" tag on the sidebar here. I covered this stuff in some detail quite a few years ago now.

@Hugh

That's not a particularly good description of monitors. They were armored, and volume was really only used for underwater protection, which is basically the only way of doing that.

Supertankers are actually much cheaper than major warships: ~$200M to build, ~$5M/year to run.

Hence, such a warship-systems-in-supertanker-hull would probably cost about the same as the equivalent normal warship. However, as already noted, it would be easier to find and slow, and not all the systems could be deep inside the hull because some need access to the outside to work.

Radar antennas might be a particular problem: the battleship era mostly relied on small things being unlikely to get hit, which doesn't work when they can be homed on.

Both Iran and the US operate forward base ships (i.e. low-end helicopter carriers) converted from oil tankers, but it seems likely that cheapness and fuel/cargo space rather than survivability was the motivation for choosing this design over a smaller purpose-built one. (Sort-of-related previous discussion.)

I am reasonably certain this would not be true at least for the first few units. I'd guess you'd build such a thing by having a naval builder do modules for all of the combat systems and shipping those off to the merchant builder who has the facilities to do a tanker-sized ship, but that's going to require both sides to do a lot of stuff they aren't used to, which drives up cost. Oh, and you'd have to keep the Navy from insisting that it be built in the way they're used to, because the tanker yard is definitely not used to that. It could be done, but the benefits definitely aren't worth the construction headache.

A worthy goal! But, wouldn't that mean the strait of Ormuz connected the Arabian Sea to Arabian Gulf? That doesn't seem kosher.

Yes, it does, and that is the one serious downside. And while that may not be kosher, I am assured that it is halal.

bean:

Problem is that along with annoying the 'government' it also annoys most of the victims of said 'government'.

Do any of you have any recommendations for a decent overview history of the Iran-Iraq war? It's been practically forgotten in the US (not that it was especially well-covered even when it was ongoing), and I'd like to know more about it.

For the Iran-Iraq war, I have "Iran at War 1500 - 1988" by Farrokh, Dr Kaveh which covers the conflict in the last few chapters. It's a sizable book, so that section is about a hundred pages. Author speaks Farsi, so has good access to Iranian sources. I haven't cross-checked, but as more of a medieval / renaissance guy nothing in the earlier chapters seemed dubious.

There's an article "The Tanker War" by O'Rourke in the May 1988 USNI Proceedings looking specifically at naval aspects, especially the use of anti shipping missiles.

@Quanticle: I haven't read it yet but I have a copy of The Iran-Iraq War by Pierre Razoux at home