In the late 1930s, the US was beginning to prepare for war. New submarines were being built, the first of the long-range "fleet boats" that would eventually starve Japan. One of these was Squalus, laid down at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on the Maine-New Hampshire border in October 1937 and commissioned 17 months later. She began to work up, making 18 dives in the waters off New England. May 23rd would see her 19th, a crash-dive while making speed on the surface to check her readiness for a major inspection coming in June.

Squalus fitting out

Like all submarines of her era, Squalus was propelled on the surface by diesel engines, and they needed air to run. This entered the sub through the main induction valve, which would hydraulically slide closed just before the submarine dived. Obviously, an induction valve failure would be a very serious issue, and the crew took precautions. The so-called Christmas Tree, which showed the status of every valve on the boat, was watched closely, and as a backup, a blast of high-pressure air was released inside the boat, producing a spike on the ship's barometer. The dive was perfect, at least until they reached 50', only 62 seconds after starting the procedure. Then, crewmen began to feel their ears pop, and a report reached the control room that the engine rooms were flooding.

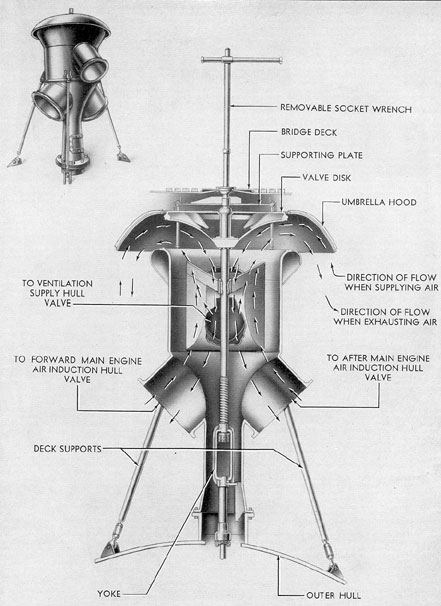

An air induction valve

The crew responded immediately, blowing the ballast tanks in an attempt to reach the surface. But it was too late, and the men aboard struggled to close watertight doors and seal ventilators. Those in the forward part of the boat barely won their race, sealing off everything aft of the control room. Some of the 26 men aft attempted to do the same in the aft torpedo room as the boat reached a crazy bow-up angle, but were overcome and drowned. Squalus sank, and the survivors wondered how deep the water below them was. If it was more than about 300', the hull would implode as water overcame steel.

The crew of Squalus wait for rescue

Immediate fears were laid to rest when Squalus found the bottom in 240' of water, and settled upright and on a more or less even keel. The captain, Oliver Naquin, ordered the marker buoy released. This was a float with a cable and a telephone inside, intended to mark the location of a sunken submarine. Squalus also had 40 smoke rockets, which would rise to the surface and then burst 80' in the air, giving rescuers some chance of locating the sunken sub. The 33 survivors set to work as best they could, despite the temperature dropping into the high 30s1 due to the cold seawater. Food and bedding was passed out, CO2 absorbents were spread on the deck and oxygen added from the emergency flasks and discussions were made of the possibility of rescue.

A submariner shows off a Momsen Lung

Submarine disasters were common in the interwar years, with 9 boats lost in the span from 1927 to 1935. Efforts had been made to produce rescue equipment, and Squalus herself carried Momsen lungs, primitive rebreathers that allowed a submariner to surface slowly, which would give time for the nitrogen bubbles in his blood to disperse. Submarine school involved using one in the 80' escape training tower at New London, but the increased depth and cold water made this extremely risky, and Naquin decided to wait for rescue. Lieutenant Commander Charles Momsen, the developer of the eponymous lung and the Navy's foremost expert on submarine rescue, had also developed a diving bell that could be lowered to a sunken submarine, mate with the hatch and take off survivors. It had been further improved by Allan McCann, to produce the McCann Rescue Chamber, one of which was on the submarine rescue ship Falcon in New London, Connecticut. If Squalus was located in time, and if the weather held, then there was a reasonable chance that the survivors could be saved.

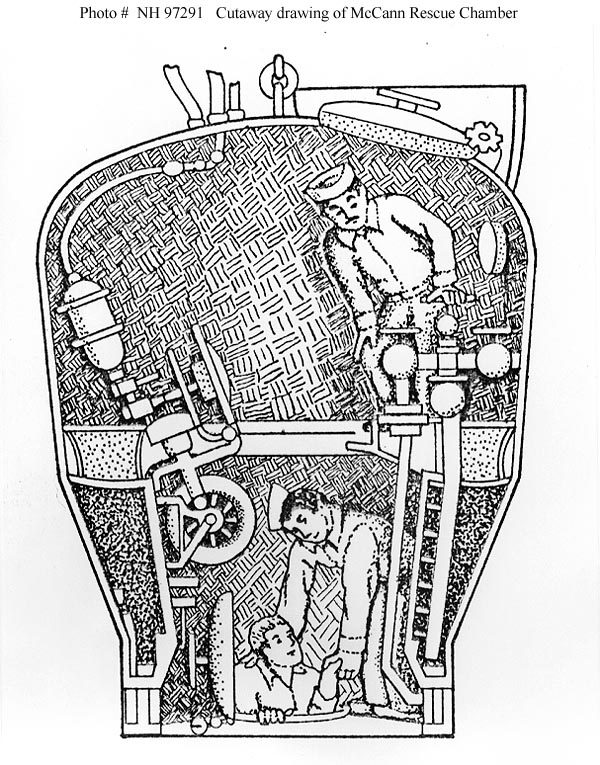

The McCann rescue chamber

When Squalus failed to report in at the conclusion of her dive, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard immediately sent her sister Sculpin out to look for her. Despite a mistake in the coordinates she was given, one of her crew spotted a distress rocket, and the men aboard Squalus quickly heard the sound of her propellers through the hull. The marker buoy was located, but after a brief exchange, an unfortunate wave snapped the telephone cable, and the line went dead. But it was enough, and Sculpin quickly radioed ashore, where the Navy's submarine rescue force swung into high gear. Falcon was ordered to the site immediately, while Momsen and the Navy's Experimental Diving Unit, probably the most experienced deep-sea organization on earth, were rounded up at the Washington Navy Yard and put on planes to Portsmouth. The weather was closing in, and one of the planes was forced to land in Newport, Rhode Island, 125 miles from Portsmouth. Police forces in three states blocked roads as the convoy rolled past, at speeds that led one diver to state that "the terrors of deepsea diving" were nothing compared to what he'd been through.2

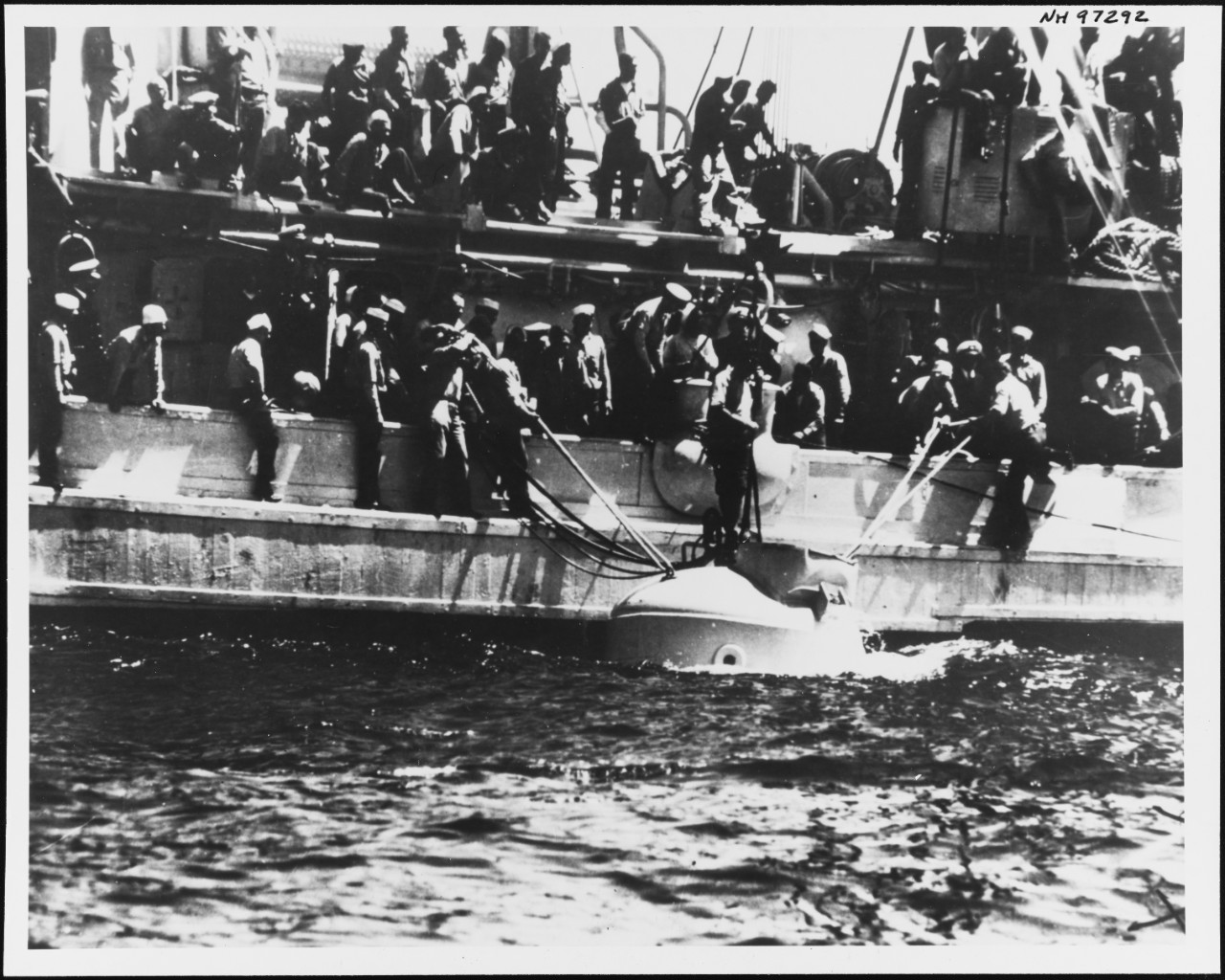

The rescue chamber aboard Falcon

Finally, at 0650 on May 24th, 21 hours after Squalus went down, Falcon arrived over the position of the submarine with the all-important rescue chamber. Momsen's group, aboard various vessels from Portsmouth, was already waiting for her, and they quickly set to work. Three and a half hours later, a diver was sent down to place the cable which would haul the rescue chamber to the forward escape hatch. With that in place, it was time for the chamber itself. Carrying two operators, John Mihalowski and Walter Harman, in the upper half of the bell, it would descend to the hatch, blow the water out of the lower half and form a seal. Despite the uncertainties inherent in carrying out such a procedure for the first time, the effort was successful, and shortly after noon, the bell touched down. The hatch was opened, and fresh air was blown in from the surface. Mihalowski passed down coffee, soup, and CO2 absorbent before taking the seven weakest survivors aboard for the return trip. The trip back up took 30 minutes, and the weakened survivors emerged into the sun on Falcon's deck to the jubilation of all.

The rescue chamber alongside Falcon

The second trip was made by William Badders, who decided to take aboard two extra survivors. Momsen, directing the salvage operation told him that he shouldn't have done it, but to go do it again. The third trip was also smooth, leaving only eight men aboard Squalus, including Naquin, who was the last to leave when the bell returned for the fourth run, now operated by Mihalowski and James McDonald. At 2014, the bell began to climb up the cable to the surface, but the winch for the cable from the Squalus became stuck at 160'. Falcon could pull the chamber to the surface, but first the cable would need to be freed, which required lowering the bell back to the seafloor. A diver was sent down to cut the cable, and despite the darkness, he was able to do so, although the chamber collided with Squalus moments later, startling the survivors. Unfortunately, the strain of lifting the bell was too much for the cable from Falcon, which began to give way. The risk of it parting entirely and taking the air line with it was too great, and the bell was lowered a third time.

A diver descends to work on the cable of the bell

The obvious solution was to attach a new cable, but two attempts by divers to do so failed when the diver's lines3 became tangled with those of the rescue chamber. The only option left was for the bell operators to bring it to the surface using its ballast tanks, with the cable pulled aboard Falcon manually. This worked, and at 0038 on May 25th, it surfaced. The survivors had been underwater for 39 hours.

The bell operators receive the Medal of Honor

On the remote chance that there were survivors in the aft torpedo room, the bell was sent down for a final time. Badders and Mihalowski made the descent, although when they opened the hatch, Badders was nearly overcome by a jet of water from the flooded interior. Mihalowski vented more air in, pushing back the water. They returned defeated to the surface, but both men, along with McDonald and bell operator Orson Crandall, were later awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the rescue.4 The rescue was widely reported, and was seen as a bright spot for the US Navy, particularly when contrasted against Japanese, French and British submarine disasters in the surrounding months. The worst of these was the loss of HMS Thetis, sunk when the inner door of a torpedo tube was opened without closing the outer door. 99 men died of the 103 aboard, despite the submarine being sunk in shallower water than Squalus.

Squalus in drydock

The decision was made to salvage Squalus, although the work was complicated by the great depth, which caused nitrogen narcosis in the salvage divers. This was overcome by the pioneering use of heliox diving mixes, replacing the nitrogen with helium. The salvage was ultimately successful after several attempts, first lifting Squalus and moving her into shallower water, and then raising her and refitting her. The exact cause of the failure was never determined, but she was recommissioned under the name Sailfish. Sailfish went on to make twelve patrols against the Japanese and sank 40,000 tons of shipping, most notably the carrier Chuyo. Postwar, her sail was preserved as a memorial at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.

1 Farenheit, not Celsius. ⇑

2 On the subject of diving, reader John Schilling has written an excellent pair of effortposts that will make it clearer what's going on with the deep-sea work here, including a bit on submarine escape in the second. ⇑

3 Note that this was before the invention of SCUBA, so all air was coming from the surface, along with a safety line. Even today, a lot of industrial diving is done using surface supply instead of SCUBA. ⇑

4 Prior to 1963, the Medal of Honor could be awarded for non-combat actions. 204 men earned the Medal this way, the vast majority of them naval personnel responding to catastrophes at sea. Only one man would earn the Medal in this way after the bell operators. Francis Hammerberg was killed in 1945 while freeing two other divers who had become trapped during the salvage effort resulting from the West Loch disaster. ⇑

Comments

I read a pop-history book about this vessel (both the sinking and the later career) relatively early in my life; and it possibly sparked a life-long interest in submarines.

And John Schilling's posts on diving made me regret not having kept up my certification; though at most I'd have an opportunity to dive maybe once a year, and usually I have higher-priority things to do on those vacations.

I've been diving twice (outside of the swimming pool I trained in) - once in a quarry for my "Final exam" for certification (which I underweighted on and consequently used up my air faster than everyone else on the dive) and once in Bermuda on a "no certification necessary" excursion where the orientation was longer than the dive.

(Cruise ship excursions for most dives not only want to see your card, but also your logbook to ensure you have done a dive in the past year or two)

Another great article Bean.

As if Momsen's work in submarine rescue weren't enough for one career, he played a role in determining the problems with the Mark 14 torpedoes in the tests on Kahoolawe, worked in Wolfpack tactics and, to round out the war, commanded the battleship South Dakota. That's a pretty impressive resume.

It sounds like only the UK has an escape training tower these days. Does everyone just use theirs, or do we not bother any more?

The USN has a new facility with a 37' pool. It's shorter than most of the old towers, but they consider it adequate.

Commander Naquin certainly seems to have led an interesting life, in the Chinese-curse sense of "interesting". Survived having two and a half ships sunk underneath him, played a supporting role in the sinking of the Indianapolis, and still managed to retire as a Rear Admiral.

The German Navy has a 32.5 m deep training facility. There is a TV documentary about it.

@John

Interesting indeed about Naquin. I am not sure how accurate this excerpt is from Wikipedia, but it certainly raises the blood pressure just reading it. Squalus, California, and New Orleans. I imagine he wasn't invited to go sailing with anyone during his retirement as Fate seemed to enjoy toying with him.

From Wikipedia: Naquin played two roles in the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. His first role as Port Director at Guam was to not inform Capt. Charles Butler McVay III of enemy submarine activity along the route from Guam to Leyte and to refuse a request for escort, making this the first time a cruiser had traveled the Philippine Sea unescorted. The trip was approximately 1,500 miles; when the USS Indianapolis sunk it was 300 miles from land. The second role Naquin played was to not follow through on being notified of a distress call from a ship in the approximate area where the USS Indianapolis would be, even once he was made aware that the USS Indianapolis was seriously overdue. His justification was that it was Navy policy to confirm a distress call and his Office sent out a reply message but did not get a return message. The reason for this policy was that the Navy wanted to be sure that the call was not an enemy trap. There were many high-ranking officers who had knowledge of the route and schedule of the USS Indianapolis voyage from Tinian to Guam to Leyte and were anticipating word of the ship's arrival in Leyte. There are many scenarios where, under proper Navy procedure the survivors could have been found at least approximately 24 hours before they were, and as soon as twenty-four hours after the sinking of the ship, which would have been forty-eight hours earlier. They were not found until a pilot on routine patrol spotted them by accident approximately seventy-one hours after the incident. It took another two days for everybody to be rescued. The crew consisted of 1,196 young men in their late teens and early twenties. Approximately 300 went down with the ship and 317 survived, with approximately 550–600 lost at sea. The twenty-four- or forty-eight-hour difference would have saved hundreds of lives, and, of course, if there had been an escort with submarine detection capability, perhaps, all could have been saved.

I'm skeptical about the part where assigning a destroyer (or really anything else) would have prevented the sinking. US and Japanese submariners have consistently testified that zig-zagging would not have mattered in that engagement, and in a 20-knot transit a destroyer's sonar would have been useless. But a destroyer would certainly have been able to mount an immediate rescue. And for that matter, dispatching a PBY to investigate even an unconfirmed distress call would seem to have been reasonable; no "trap" the IJN could plausibly have implemented in 1945 would have caught a reasonably cautious patrol aircraft.

Mostly, Naquin seems to have had a talent for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Aside from the Indianapolis incident, he seems to have done the right thing every time. And there's plenty of people (and fish) to share the blame for that one.

Indianapolis is a complicated issue, and one I'm not planning to cover because there are already too many books on it. The short version is that a 20-kt transit shouldn't really have been that vulnerable to the submarines of the day, and Indy just got unlucky on that front, and on the front where she went down very fast. Northampton took 3 hours to sink after being hit by 2 torpedoes, while Chicago survived the first two and only went down after 4 more hits. Houston also took 4, and I believe took longer to sink. I don't think Astoria took any torpedo hits, and Quincy and Vincennes both were hit by shells in addition to the torpedoes (which were Long Lances, and not sub torpedoes). Helena took 3 hits, too.

In fairness, I believe most or all of those ships were at GQ and thus presumably more buttoned up than Indianapolis. In fact, the only other American cruiser I can think of which was lost in a similar way was the Belgrano, and she was being run by an organization much less competent than the 1945 USN. But I still think that Indianapolis must have gotten hit in really bad spots to go down as quickly as she did from two torpedoes.

@John Schilling: somewhat related, but Indianapolis is basically the start of the Navy's attitude of "Something bad happened, so let's fire some people, regardless of whether it's deserved or not"

I think the roots go further back than that. Husband Kimmel springs to mind.

And I think that attitude has done great harm to the Navy's ability to learn from trouble, since the immediate impulses are "find someone to punish" and "try really hard not to be the guy who gets punished".

I completely agree. I remember hearing about an RN Admiral who'd had a collision as a junior officer. He'd gotten a letter about it that started "today, you became a better seaman". But I also think Naquin is an even earlier example than Kimmel. He was basically kicked out of the submarine service after the Squalus sank, despite it being not his fault in any way.

There's a book I can highly recommend on the subject of the firing culture of the USN, Crimes of Command, by Michael Junge. He talks some about how the Indy case set a precedent for how the Navy would think about firing people. Biggest differences between Kimmel and McVay were Kimmel had a lot more authority to do something (it's hard to tell if McVay doing things differently would have made much of a difference), and there was no precedent for losing a single ship due to enemy action in war time, especially when a lot of more senior people should also have been at least somewhat culpable (instead of sitting on the Court of Inquiry-coughcough, VADM Murray, COMNAVREGMARIANAS).

And it still might have been an aberration except for the cultural changes wrought by a certain flag officer who will not be named (but to narrow it down, he held flag rank for almost 30 years).

Disclaimer: I consider the author a friend and mentor, so I am biased towards the book. But it is a great look at the culture of "Accountability" and How We Got Here.

There's a reason that every time the Navy nuke people came by my school (which had a nuclear engineering program and nothing else of interest to the USN) instead of talking to them, I would just go by to point and laugh.

Thank you for that recommendation Blackshoe.

How did Nimitz move up after his incident in the Decatur? Was it a more enlightened time of "learn from it and don't let that happen again?"

@Neal: short answer is it was a more enlightened time that understood the concept of forgiveness for errors, a culture that Rickover (and especially some of his disciples) got rid of. Long answer is more complicated, as it always is.

Thanks Blackshoe. I ordered the book and look forward to tucking into it.

I watched an episode of the series 'Voyages of Discovery' about the Squalus (the final episode, Hanging by a Thread). If you have access to the BBC iPlayer, I think it's worth watching.