One thing I didn't bring up much in my discussions of the early battleships was their interaction with coastal defenses. This is largely because it is most prominent in John Beeler's Birth of the Battleship, which I hadn't read yet, and Friedman's British Battleships of the Victorian Era, which wasn't out yet when I wrote those. But as I've learned more about that, and coastal defenses in general, I think it plays an important part in the design history of the battleship in the period between 1860 and 1890.

The British bombard Sveaborg

Fundamentally, there are three ways to deal with an enemy battlefleet: defeat it on the open seas, blockade it into port, and destroy it in its base. During the age of sail, it was rare for the third option to be on the table, as coastal defenses were too strong for a fleet to have any real chance of defeating them.1 But this began to change in the 1850s. During the Crimean War, the British showed that the greater maneuverability of steam-powered vessels opened up new options for attacking coastal fortifications, while the American Civil War confirmed the ineffectiveness of masonry fortifications in the face of fire from rifled guns. In both wars, the ironclad raised the minimum standard required of coastal guns. All of these combined to make existing fortifications obsolete, which was essentially a new problem for coastal defenses. Previously, even decades-old guns in hasty or antique positions could provide quite effective coastal defense, particularly if paired with heated shot or shells. But facing down an ironclad would require expensive modern guns, which were only available in limited numbers, and which were rapidly rendered obsolete.

This left an opening which the RN thought it could exploit. Steam had rendered its traditional close blockades dubious. Coal endurance was woefully insufficient for the amount of time the ships would need to spend on station, and while their battleships still had sails, they would be at a serious disadvantage if the French came out to fight under steam. Waiting in harbor for the French to come out and trying to catch them at sea might well fail, and offered the French the opportunity to send out commerce raiders, a critical threat to the maritime trade that drove the British economy. But the changes in the balance between ships and coastal defenses offered the possibility of attacking the threat at its source.

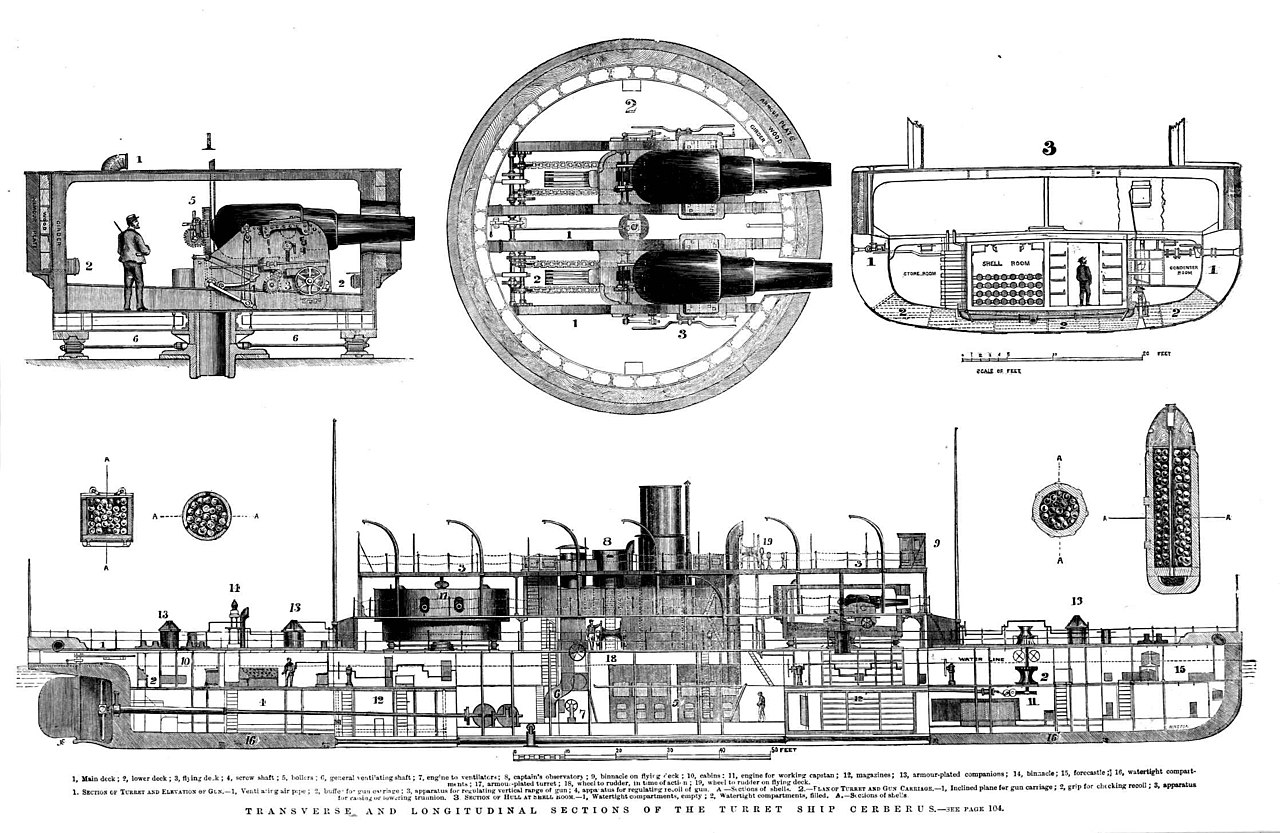

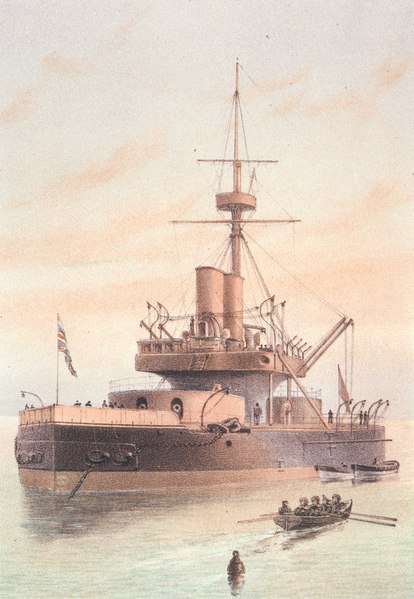

HMVS Cerberus

The result was a series of ships optimized for coastal attack, which unsurprisingly drew many elements from the American monitors, designed to meet a very similar role. Turrets were useful in ensuring that the ship could continue to fire whatever its orientation, while the lack of freeboard would reduce target area. Because the ships would operate inshore, they would not be hindered nearly as badly by seas on deck as they would on the open sea. To mitigate this slightly, Edward Reed put the turrets and superstructure on a projecting breastwork, which at least kept water from going down into the engines. Officially, the first vessels of this type were labeled coastal defense vessels, and several of them really were, most notably the first two, Cerberus, built for the Australian state of Victoria, and Magdala, built for Bombay. But they were followed by four very similar ships that served in home waters, and the basic design was scaled up into Devastation, Thunderer and Dreadnought, the first seagoing battleships without sails.

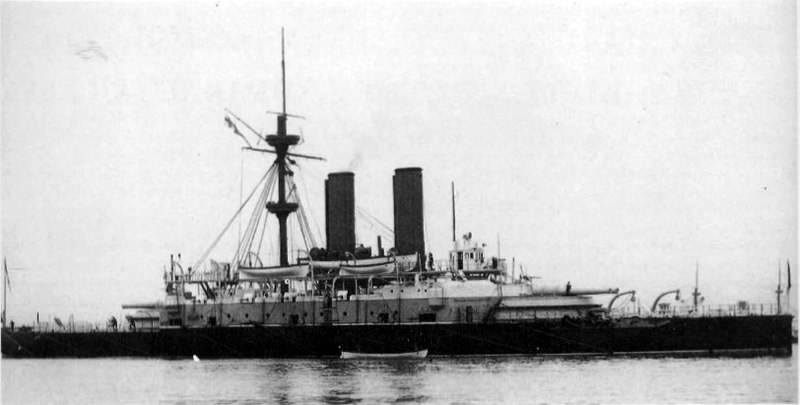

HMS Dreadnought

All of this seems like it goes some way to explain British interest in the low-freeboard turret ship, and their disdain for the barbette. The open-topped barbette would be extremely dangerous near the shore, where it would be easy for a defender to find an elevated firing position and slaughter the crew with lighter weapons. And given the conditions prevailing in the period 1865-1875, it made a lot of sense. The French probably wouldn't bring their fleet out to fight at sea, and there was little chance they would invest in coastal defenses capable of facing down the most modern coastal-attack ships, so optimizing ships for the role was a good plan. However, it fell apart in the second half of the 1870s, thanks primarily to the invention of the torpedo. At the beginning of the decade, the only threat to the battleship was the extremely expensive big gun.2 A torpedo could be deployed from a small boat or a shore battery, and it could threaten even the biggest battleship. Adding to this was the fact that it appeared that gun development had begun to plateau, making investment in gun-based coastal defenses at least somewhat more sensible. In the face of all this, attack at source was much less attractive, meaning that battleships should probably be optimized to meet their opposite numbers at sea.

HMS Collingwood of the Admiral class

But the British continued to be fond of the turret until the late 1880s. With the exception of the Admiral class, all of the vessels built during this period were in the mold of the coastal-attack vessels of the early 1870s. This appears to have been primarily the result of technological conservatism and the lack of the sort of analytical capability we take for granted today. The RN didn't get any sort of staff until the late 1870s, and it was focused mostly on gathering intelligence on foreign navies. Warship design was the preserve of the DNC, and while that office was occupied by a succession of exceptionally able men, they had to contend with the whims of politicians and service officers who in many cases were not particularly interested in innovation. In such cases, the next class of ships is likely to be a straightforward development of the previous class, even if the decisions that drove that class don't make much sense any more.

Another aspect of the problem is a general lack of sea experience with alternative designs. While Warrior was in commission 2 years after she was laid down in 1859, Devastation took 3.5 years to reach service from when she was laid down a decade later. By the middle of the 1870s, things were much worse, with Inflexible, laid down in 1874, taking a full seven years to be commissioned. The first mastless ship with high-mounted guns, Collingwood, didn't commission until 1887, a mere two years before the revolutionary Royal Sovereigns were ordered, and her experience had a direct impact on the decision to fit those ships with barbettes.

All of this is somewhat speculative, as I'm working out the argument here for a project I have going on, and these are usually improved by getting other eyes on it. I've checked all of the details it seems reasonable to look over, but there's a lot going on, and I might have missed something.

1 There were occasional cases where this might not hold, or where conditions might be right for a fireship attack, but these were pretty rare, and definitely couldn't be counted on as strategy. ⇑

2 Ramming might have also figured into the picture, but a ram capable of attacking a battleship wasn't exactly cheap. ⇑

Comments

The only example I remember is Copenhagen, and even that required a sneak attack on a peace-time navy and very nearly ended in disaster for the British.

Off the top of my head, another example is the Raid on the Medway. Another sneak attack, but that's standard for attacking a fleet at anchor, even after the age of sail: see, for example, Taranto and Pearl Harbor.

@DampOctpus

I mean that all of the above were cases in which the attacker had the element of surprise, rather than a fleet action on the open seas in which (I think?) both sides were usually aware beforehand that a battle was about to occur.

In fact, looking more closely, I don't think the Battle of Copenhagen meets that criterion: the British fleet arrived on 15 August 1807, but the attack didn't actually start until 2 September, after several weeks of (unsuccessful) negotiations.

Copenhagen is a good call. I was thinking of the fireship attack on the Armada, and the Medway does also count, but the battles in question are notable by their rarity.

I think 1801 Copenhagen does. 1807 probably doesn't. Among other things, it was largely a land attack, which is a rather different thing.

Oops - I missed that there were two Battles of Copenhagen.

Another case of an attack on a fleet at anchor: Navarino (1827).

Bean, were these early British monitors ever used as intended? Non-existent is rarer than rare - though I'll grant that the window is narrow compared to the entire age of sail. And non-use might actually be an indication that they were effective as a deterrent.

@DampOctopus

Navarino was indeed an attack on a fleet at anchor, as was Aboukir, but in neither case was the fleet being attacked in a fortified home base.

...CERBERUS technically still exists - her hulk rests in about 10 feet of water off the Australian coast. There's been efforts to raise/preserve her, but they never seem to get very far. She's the last 'surviving' vessel with Coles turrets, and as such deserves some kind of preservation.

I suspect being the first ironclad owned by an Australian colony is more historically significant (at least to those nearby) than the turrets it was fitted with.

I'm still shocked ironclads like Cerberus could survive a trip down to Australia, or spend five minutes in the north sea without getting swamped or rolling over.

For delivery to Australia, Cerberus was fitted with wooden bulwarks at the deck edge and a set of masts. I wouldn't have wanted to try to deliver her in operational configuration, either.

I'm starting to question the basic logic here a bit. Digging into other stuff, I ran across something from 1883 which is drawing a very strong distinction between European battleships and worldwide battleships, with Devastation/Dreadnought being the European side. In that case, it's basically as soon as steam engines got good enough to make them practical, they arrived, without any coastal contribution.

I am getting sick of rewriting that section.