Over the years, naval architects have come up with a variety of unusual hull types for specialized roles, and it's worth taking a look at some of them. There are benefits and drawbacks to any departure from the conventional monohull, and while for most roles, the tradeoffs aren't worth it, a few have seen reasonably wide use. We'll start with the oldest of these by far, the multihull. Typically, these can be divided into catamarans, with two fairly similar hulls and trimarans, with a single big hull in the middle and two smaller hulls out on the sides.

A replica Polynesian catamaran

The basic idea of making a ship with more than one fairly conventional hull dates back to the outrigger boats used by the Austronesians in their expansion across the Pacific. At first, these were simply two dugout canoes with a platform between them, a design probably adopted in search of the great advantage of the multihull, excellent stability. The reason for this is extremely straightforward. Stability is the resistance of a ship to rolling over, and it comes from hull on the downward side being pushed deeper and displacing more water while the hull on the upward side displaces less. On a catamaran, with the hulls split apart, this effect is significantly stronger, a useful feature if you are planning to carry a large sail on a small boat. But any case where there are two or more separate points of contact with the water can produce the same effect, and the Austronesian catamaran eventually evolved into the more typical outrigger designs used in the astonishing expansion across the Pacific Ocean.1

No, Dean, the word catamaran comes from Tamil and has nothing to do with cats.2

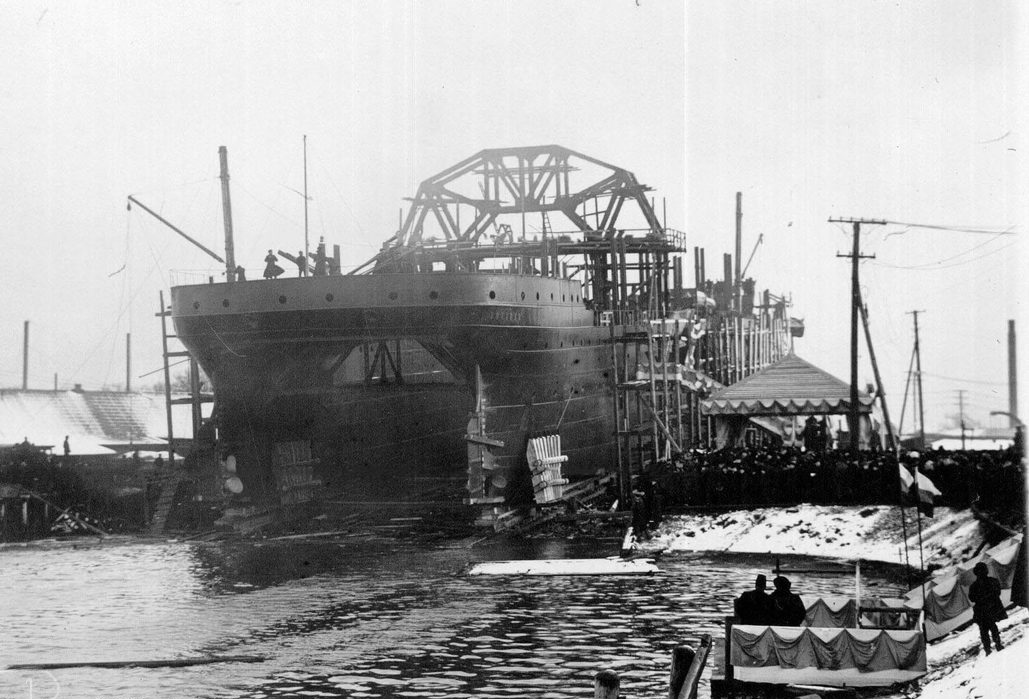

With a few minor exceptions,3 multihull designs saw little use outside the Austronesian world until the late 19th century, when sailing yacht designers looking for higher performance began adopting the type.4 The first broad adoption by people using modern propulsion came in the early 20th century, as several nations, concerned about the loss rate among their new submarine forces, built catamaran vessels intended to provide rescue support to sunken submarines. The catamaran design allowed the rescue equipment to be lowered between the hulls, greatly simplifying the working arrangements versus having to dangle stuff over the side using booms and allowing it to enter the water at the point of minimum motion. One of these, the Russian Kommuna, commissioned in 1915, is the oldest naval vessel still in active service.

Volkhov, now Kommuna, launched in 1913

Eventually, submarines grew more reliable and the catamaran faded out of use for most of the 20th century. But the multihull has seen a resurgence in more recent years, alongside the trimaran, as designers have sought higher speeds. For various and complex hydrodynamic reasons, a catamaran or trimaran will have reduced wavemaking resistance relative to a monohull, although at lower speeds this is entirely offset by the increase in frictional resistance that comes from multiple hulls. But as speed requirements rise well above hull speed and wavemaking resistance comes to dominate, the advantages of the multihull become more pronounced. Starting in the 90s, the type rose to dominate the high-speed ferry market, which had previously been the domain of hydrofoils and hovercraft. Some were catamarans, usually with wave-piercing bows designed to minimize pitching as the ship passed through the sea, while others were trimarans, taking advantage of the fact that the outer hulls, smaller than the main hull, could be positioned to partially cancel out the waves from the central hull, increasing efficiency. In both cases, significant structural concerns had to be overcome, but these have been dealt with, and the multihull has a clear niche in the short-range high-speed low-weight market, primarily from Australian companies Incat (builder of catamarans) and Austal (trimarans).

Spearhead class City of Bismarck

Of course, that brings us to the military use of multihulls. A few slow multihulls exist, like the American Pigeon class submarine rescue ships of the 1960s, but the main use has come as navies have desired higher speeds. The first vessel of this type was HMAS Jervis Bay, a former catamaran ferry chartered by the Australian Navy in the late 90s which proved extremely useful during the Australian intervention in East Timor. The USN saw this and decided that it looked like a good idea, despite the lack of places within a few hundred miles of US bases where intervention might be necessary. They decided to test this out with the Joint High-Speed Vessel Program, which chartered a pair of ferries. For some reason, this wasn't enough to put them off the idea, and starting in 2010, 15 Spearhead class fast transports were procured, each intended to be able to carry a mechanized company or infantry battalion a thousand miles at 45 kts and unload it at a primitive pier. The only problem is that this requires calm seas, with the maximum speed being achievable only if the waves are less than 1.25 m, while rougher seas quickly reduce available performance below that of conventional vessels. It's not clear what problem this is supposed to solve, or why we keep buying them.5 And because they're made of aluminum, there are serious concerns about how they'll handle damage if someone shoots at them, as happened to HSV-2 Swift in Emirati service off the coast of Yemen.

Independence in drydock, clearly showing her three hulls

But there are also a few multihull combat warships, by far and away the most famous of which are the Independence class Littoral Combat Ships. Conceived as part of a dubious plan to develop 45-kt corvettes for fighting Iranian speedboats in the Arabian Gulf, they have shown a major advantage of multihull warships even if you don't want to go fast. Unlike warships through WWII, modern warships are generally constrained by volume and deck space, and a multihull offers far more of both for a given displacement. This is best shown by comparing the Independence to the monohull Freedom class, designed to the same specification. Independence has a flight deck that is approximately6 128' long and 80' wide, while Freedom's is only 92' long and 57' wide. This is by far the best flight deck available on any surface combatant, and I expect the trimaran configuration to see wider adoption for small helicopter carriers in the next few decades.

A Type 022 missile boat at speed

The other multihull warships are smaller and designed to operate in the world's most contested seas. The Chinese have built over 80 examples of the Type 022 missile boat, which serve as highly mobile missile batteries in defense of the South China Sea. On the other side of the Taiwan Strait, the larger Tuo Chiang class corvettes, equipped not only with anti-ship missiles but also sporting some air-defense capability and even a 76 mm gun. Both are capable of the same 45 kts or so that the Independence can manage, and are stealthy, at least in theory.

Francisco, the world's fastest passenger ship

But operating at high speed, as both of these vessels do, is often rather rough on the ship and its crew. Further hull tweaks, either to catamarans or to monohulls, can significantly mitigate this, and we'll take a look at these next time.

1 I don't have a good link to drop here, but if you're interested, check out the opening chapters of David Abulafia's The Boundless Sea. ⇑

2 Thanks to quanticle for his help taking this photo. No cats were harmed in the making of it. ⇑

3 Most relevantly, there was Robert Fulton's Demologos, the world's first steam-powered warship, which had two hulls with a paddle wheel between them, although the tessarakonteres, an enormous catamaran galley from Ptolomaic Egypt, also bears mentioning. Neither was a success. ⇑

4 At this point, I have to drop in a story about multihull sailing yachts. The America's Cup, the highest prize in international yacht racing, has a very strange legal setup, where the competition is controlled by the Deed of Gift which lays out the basic rules for running the competition, structured as a set of races between the "defender", who last won the cup, and the "challenger" yacht club. Normally, the two agree on rules, and these days there's even a qualifying series for the challengers. In 1988, just after the San Diego Yacht Club recovered the Cup for the US from the perfidious Australians, New Zealand banker Michael Fay issued a challenge and insisted that it be run to strict Deed of Gift rules instead of the 12-metre class that had been in use for several years. San Diego tried to ignore him, but he went to court to enforce his challenge, and the court agreed with him. San Diego was annoyed, particularly as Fay had already built his challenger, so they re-read the Deed of Gift and noticed that it didn't actually say their yacht had to be a monohull. Fay sued, arguing that using a catamaran was cheating, but the court effectively said "live by the Deed of Gift, die by the Deed of Gift", and San Diego's yacht went on to trounce him in the 1988 America's Cup. Multihulls went away until the 2010 America's Cup, which was a Deed of Gift match even more spectacularly petty than the 1988 version, with hydrofoils added for the next match in 2013. Multihulls stuck around for a few years, although the series is currently run in foiling monohulls. ⇑

5 OK, that last bit is a lie. It's entirely clear why we keep buying them. It's the main project at Austal's yard in Mobile, and the Alabama congressional delegation is being as irritating as ever. ⇑

6 Numbers are approximate because I had to generate them by measuring pictures, due to the lack of published values. ⇑

Comments

Australian catamaran and trimaran ferries really started to take off in the 1980s rather than the 1990s. I remember in the mid 80s that just about all the new ferries being used on the Great Barrier Reef were "cats" and that was seen as a good guide as to whether you were looking at a new boat or an old one. Relevant that the sea within the Great Barrier Reef is all very sheltered by the outer reef so for sea travel the waves are very small, typically 1 to 2m at most in normal weather.

It started in Australia and spread elsewhere, but it looks like they didn't take over the top end of the ferry market (from hydrofoils and hovercraft) until the 90s.

"Independence has a flight deck that is approximately 128′ long and 80′ wide ...omissis... . This is by far the best flight deck available on any surface combatant..."

All the aircraft carriers are grey with envy...

:-D

@Emilio: the phrase "surface combatant" usually implies "not a submarine or a carrier". And yes, that does mean this record is basically a matter of definition; more meaningful is that it's an unusually big deck compared to the ship's displacement.

Technically, it also excludes amphibious ships, because I didn't want to have to measure a San Antonio. An extremely rough estimate says that's bigger (~195'x100'), but it's not that much bigger, and the San Antonios displace 25,000 tons (vs 3100 for Independence) and are capable of about half the speed.

" Multihulls continued to be used up until 2017, with hydrofoils added in 2013"

Not to well, actually, but, between the two Deed of Gift matches mentioned, America's Cup was competed with International America's Cup Class monohulls. So other than the DOG matches, only two other years were raced with multihulls- 2013 and 2017.

Oops. I had completely misremembered that. Will fix.

@muddywaters, so we also have to discount the Vittorio Veneto (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/it/c/c1/Venetoimpetuosomargottini.jpg ) and the Moskva?

Those are weird edge cases. I think they would normally be counted as "not surface combatants" on the grounds that they are clearly much more for aviation operations than, say, a typical destroyer is.

bean,

Is SWATH not a kind of catamaran, or are they going to be the star of another article? I know those get used a fair amount in special mission ships.

It is a type of catamaran, and it is going to be the star of another article. This coming week's, in fact.

My sources are only from Wikipedia, but I would say that attack on the HSV-2 Swift shows that aluminium multihulls have pretty good damage sustainability. They hit them with anti-ship missile and without military crew they were still able to survive. Which would be huge achievement even for military ship of this size (1600 tones, so average corvette).

Is it possible that multihulls are just more resilient to damage because of their construction?

Why wasn't the torpedo boat / early destroyer a multihull?

They look like they could use the extra speed, but it seems likely that enough people knew of the sailing type that if that actually was a good idea, someone would have thought of it at the time.

Structural issues (either making it outright impossible, or adding enough weight that it ended up slower)? Worse low-speed efficiency = more fuel weight? Propeller limitations (the concept of a waterjet existed, but a practical implementation possibly didn't)? Something else?

I took Incat hull 25 across the English channel when the hovercraft were grounded for bad weather. They might be more stable, but it's an extremely unpleasant experience (plus I missed my only chance to ride a hovercraft short of joining the Russian Marines)

@BerndL: it's a known issue that being too stable can be uncomfortable because of the short roll period.

(It was also bad for shooting accuracy when that was roll-limited (pre ~1917), which might be part of why there weren't multihull destroyers.)

I don't think that the advantages of multihulls for speed were appreciated that early, even assuming they apply at torpedo boat scales. The speed advantage for sailing multihulls (at least before the last 50 years or so) is generally more from being much more stable and thus able to carry a lot more sail. Just to be sure, I checked the indexes of both the Bacon and Mackay biographies of Fisher, neither of which had an entry for catamaran, and if Jackie Fisher didn't advocate for it, then it was really outside the realm of the possible.

The Independence class is listed as 7300 sqft, which doesn't actually match the dimensions you quote (being some 75% of that value), but it's possible that the "flight deck" does not include all the area of the actual deck. It might only count the marked space on the deck.

Why wasn't the torpedo boat a multihull?

My book "Introduction to Naval Architecture" from 1982 (Gilmer & Johnson, USNI Press) just says that multihulls are for when you need exceptional stability and/or deck area. This seems to be why the Polynesians used them: small wooden boats sailing hundreds to thousands of kms on the Pacific don't need to be particularly fast.

My inexpert explanation would be that until very powerful marine diesels exist late WW2, and gas turbines post WW2, two or three small engines cannot add up to the power output of one big engine. Not a problem for sailing boats which have the "engine" above deck. Big problem for steam triple expansion or turbine engines which don't scale down very well. So any potential speed advantage from the catamaran / trimaran hull would be outweighed by the inefficiencies of the engines.

@CmdrKein

I did actually cross-check my value with Wiki (and a bunch of other places), which credit Independence with 11,000 ft2. That's close enough to my number that I'm reasonably confident in it, and I don't see how I could have gotten the measurement that wrong, either.

Hugh Fisher:

Yet they could go almost as fast as modern racing yachts.

@Anonymous, the Polynesians did not need speed, but they got it anyway because as bean points out they could carry more sail. Multihulls are a good design for some purposes, I didn't write that they're automatically bad or slow.

I am confident that the Polynesians weren't optimising for speed above all else like racing yacht designers, and in the context of the original question about early torpedo boats a catamaran / trimaran would not have been a good choice.

I see that the Navy has begun deactivating the Spearhead-class fast transports, with at least one headed for the scrap yard. All less than 15 years old. news.usni.org/2025/09/17/navy-decommissioning-last-ships-before-fiscal-years-end