The jet engine represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in the history of aviation, but the jet age did not spring fully formed from the brow of Frank Whittle. Over the last 80 years, the push and pull of technology and response has seen the emergence of 5 distinct generations of jet fighter, with a 6th currently in development. These generations are more than a simple catalog of models; each represents fundamental shifts in operational capability and design philosophy. Understanding what makes each generation unique and how it came about makes it easier to understand the evolution of air power, the process of technological change, and how the simple interceptor of the 1940s became the complex, networked weapons system of the 21st century.

Gen 1

An Me 262, a bad fighter jet

Gen 0: Meteor, Me 262, P-80, F2H

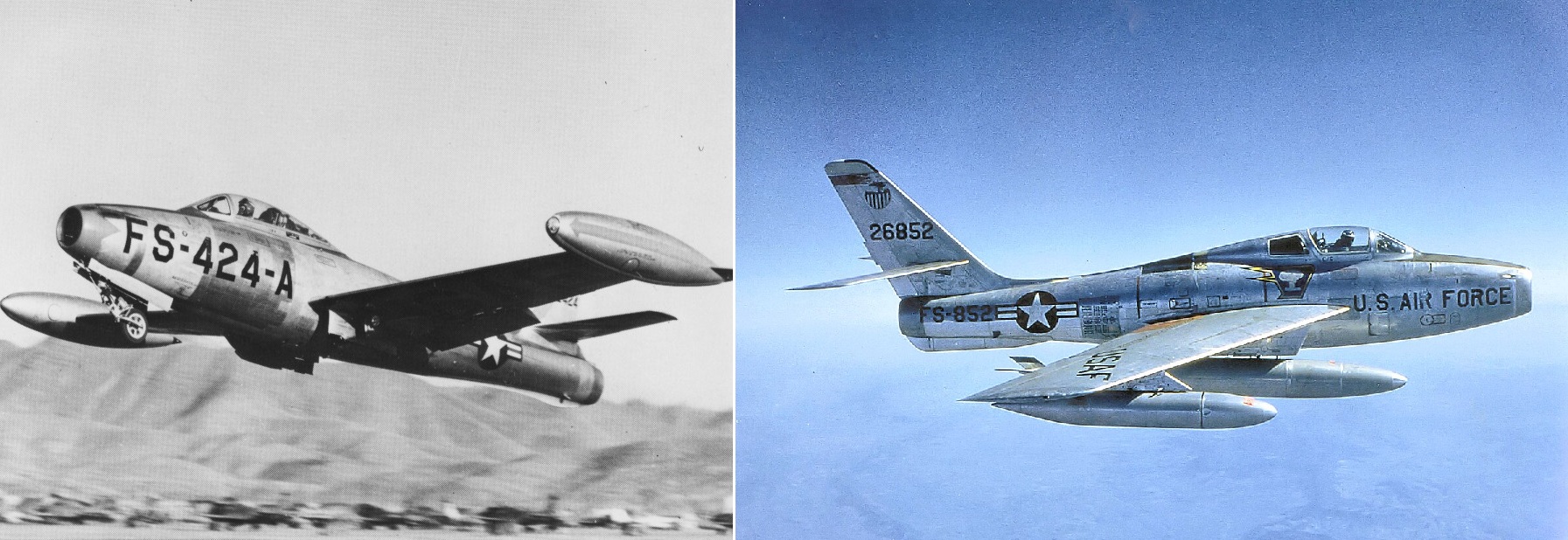

Gen 1: F-86, MiG-15, Tunnan

Our story begins with the jet fighters that emerged during the Second World War. Of these, the Messerschmitt Me 262 is by far the most famous, but the Gloster Meteor and Lockheed P-80 also saw limited service in the war. These early jets are sometimes referred to as 0th generation fighters to distinguish them from the proper jet designs that emerged a few years later, but they are grouped here because of the short period of time Gen0 would cover and because Gen0 and Gen1 have more in common than not.

Speed

Before anything else, the jet made fighters faster. During World War Two, the quest for more speed saw the development of truly colossal piston engines. A late war R-2800 Double Wasp engine had 18 cylinders and a displacement (i.e. total cylinder volume) of 46 liters. That meant each cylinder had about as much displacement as the entire engine of a modern car.

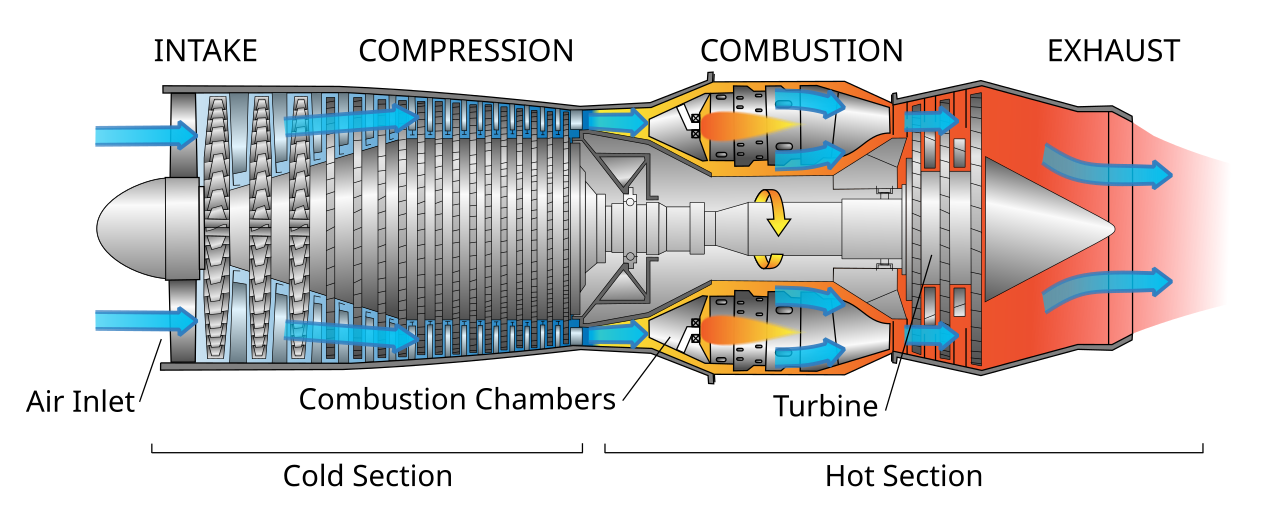

Both jets and pistons are heat engines that operate in four stages, often summarized as “suck, squeeze, bang, blow.” They suck in air, compress it, ignite it (which causes it to expand), then expel it, converting the fuel’s chemical energy into mechanical energy. In a piston engine, this reaction is confined to a piston, and the mechanical energy pushes a cylinder that turns a driveshaft to power a propeller. This process is mechanically complicated, with a great many parts moving in opposite directions. Keeping the whole engine running together and not overheating grew harder and harder as engines got bigger and bigger.

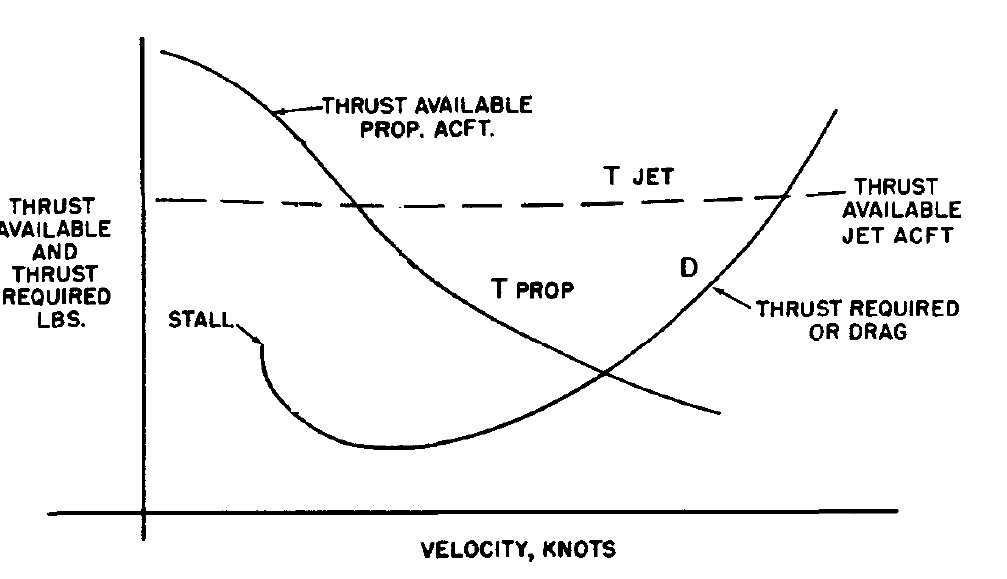

Worse, even if you could get more power, you couldn’t use it. The engine of a prop powered aircraft doesn’t move the plane directly, it spins a propeller that pushes air to generate thrust. To go faster you need to push more air, which means a bigger or faster propeller. Unfortunately, propeller efficiency drops off rapidly as both the plane and the propeller spin faster. These two factors conspired to limit the maximum speed of propeller driven aircraft.

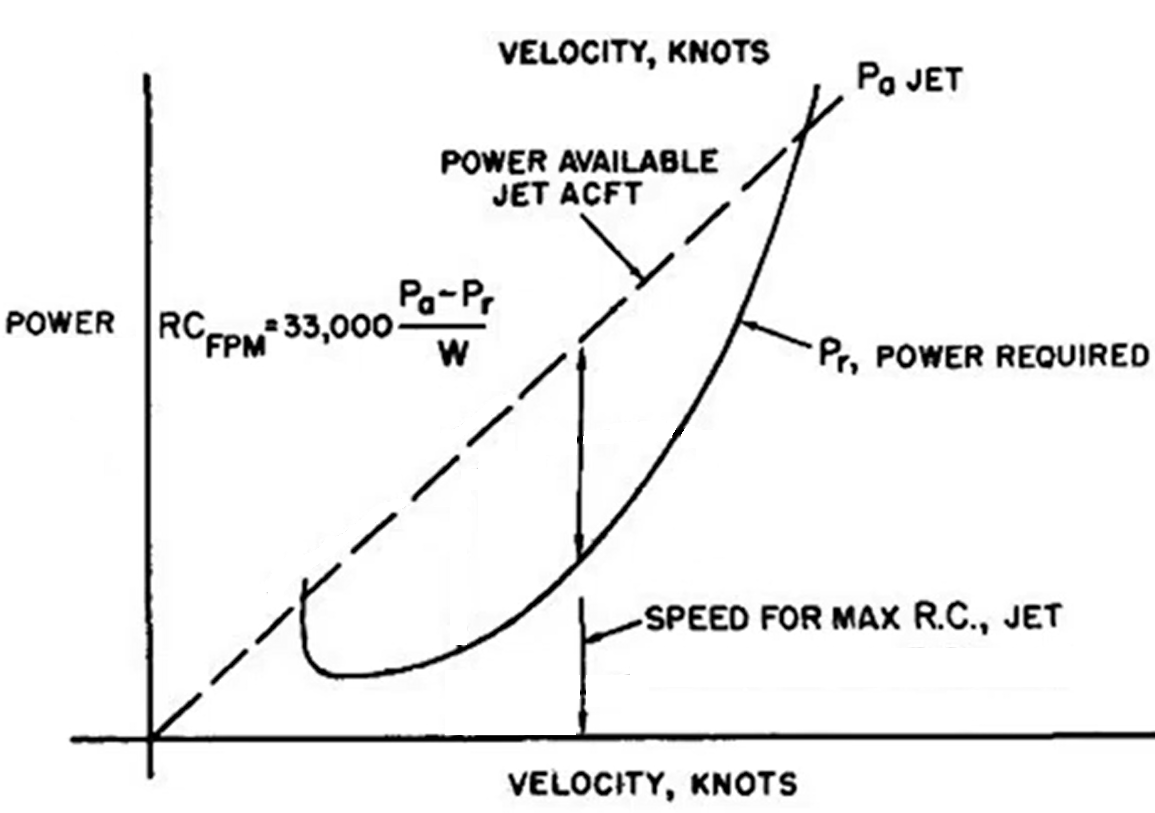

Jet engines solve both problems. Instead of compressors, pistons, valves, crankshafts, drive shafts, and transmissions all moving in a different directions, jet engines ingest air, compress it with a series of fans (all of which spin the same direction), ignite it, and blow it out the back of the plane, directly producing thrust. Not only is this mechanically simpler (and thus more reliable), the lack of reliance on a propeller means thrust does not drop off with speed.

As a result, jets are fast. The Me 262 was designed to reduce production cost and time above all other requirements. It was powered by engines made out of sheet metal assembled by slave labor. The build quality was abysmal and engine life was so low that pilots reported they could feel power declining over the course of a single flight. Despite this, while even the best late war piston fighters had top speeds in the 400-450mph range, the Me 262 was capable of well over 500mph, while the better Gen0 jets could exceed 600mph.

Once freed from wartime restrictions on development, jet engine performance improved rapidly. Understanding of high speed aerodynamics improved as well, most visibly in the adoption of swept wings. A great example of the transition from Gen0 to Gen1 is the F-84. After a somewhat troubled development the first truly successful version of the aircraft (the F-84E) entered service in 1950 with a top speed of 620mph. Just 4 years later, the F-84F, redesigned with swept wings and a more powerful engine, could fly at 700mph.

F-84E and F-84F

While attempts were to build faster prop powered aircraft, the fundamental limits on the performance of props proved difficult to overcome. Few production aircraft powered by props can reliably exceed 500mph, with the 4 engined Tu-95 bomber and its derivatives perhaps the most notable exception. Within just a few years of the end of World War two, it was clear that the future of speed belonged to jets.

Armament

By the end of the First World War, the standard armament for fighter aircraft was a pair of forward firing machine guns firing rifle caliber ammunition (usually around .30). Planes of the day were built mostly out of wood, wrapped in fabric, and powered by engines that constantly leaked oil. They would burst into flames if you looked at them too hard, so no more firepower was needed.

All metal planes changed this. Metal aircraft were far more durable and their higher speeds meant pilots had less time on target. Shooting them down demanded an increase in firepower, and the late 30s and 40s saw tremendous experimentation in how to provide that. More machine guns were added, then larger machine guns, and eventually cannons firing explosive shells.

20 mm cannons in the wing of a Skyraider

Gen0 and Gen1 jets saw the culmination of this trend. While the US clung to the .50 cal machine gun longer than most, most of these fighters were armed with 2-4 cannons of 20-40mm caliber. These cannons differed from machine guns in firing explosive shells, greatly increasing the damage dealt by a single hit, while retaining a high enough rate of fire not to complicate hitting the target and allowing for sufficient ammunition storage. Like their predecessors, most were capable of carrying bombs and rockets on wing mounted pylons.

The primary sensor for aiming these weapons was the Mark 1 eyeball, though it was supplemented with increasingly sophisticated gunsights that sometimes incorporated simple radar systems. Proper search radars were limited to specialized night fighters.

Size

While the jets were powerful, they were also far less fuel efficient than the piston engines they replaced. This meant that more fuel was needed, so planes had to grow. Late Second World War fighters would have a maximum take-off weight (MTOW) in the range of 10,000 - 15,000lbs. The North American F-86 clocked in at over 18,000, McDonnell F2H over 25,000. This increase in size led to a commensurate increase in cost.

Early jet fighters came with a lot of struggle and challenges. They were harder to fly than their predecessors, particularly at low speeds and they had limited endurance despite their size. But the Korean War made it clear the performance advantage of fighter jets was too big to ignore. Piston-engined aircraft would continue to serve in support roles; they continue doing that even today, but not as fighters. The age of the fighter jet had begun and there would be no turning back.

Gen 2

F-100, Mig-21, F-104

The second generation of fighters emerged after the Korean war, and almost everything about them was shaped by the demands of supersonic flight. Getting beyond the sound barrier required new advances in engine technology, new understandings of aerodynamics, and new types of weapons and sensors. This is the first generation that starts to look and operate like modern fighters.

MiG-21, a better fighter jet

Supersonic Aerodynamics & Afterburners

While we often talk about planes flying through the air, the reality is that planes have to push air out of their way. The resistance this creates is called drag, and the amount created is determined largely by the shape and speed of the object creating it. As aircraft designers began trying to build supersonic aircraft, they quickly realized that many of the shapes efficient for subsonic flight were terrible for supersonic performance. Worse, not all the pushed air moves at the same speed. As a plane approaches the speed of sound, some of the air moves around it faster than the speed of sound and some slower. This creates enormous amounts of drag and is why the sound barrier is a barrier. The zone where this happens is called the transonic zone and while the size of the zone depends on the shape of the aircraft, it usually begins at about Mach .851 and persists to about Mach 1.2.

This posed a problem for designers. Previous generations of aircraft had increased speed gradually over time, dealing with new challenges as they showed up. But because planes can’t operate efficiently in the transonic zone, going a little bit faster wasn’t an option. They had to jump all the way from Mach ~.9 to 1.5 or more in a single generation, and this posed huge problems for aircraft design.

The first requirement was for more thrust, a lot more. Higher speed requires exponentially more power. Engines had substantially improved since Gen1, but not enough to meet the needs of supersonic flight. The solution was the afterburner. These devices dumped fuel directly into the engine after the turbine. This dramatically increased their thrust at the cost of a huge increase in fuel consumption, allowing super sonic flight, at least for limited periods of time.

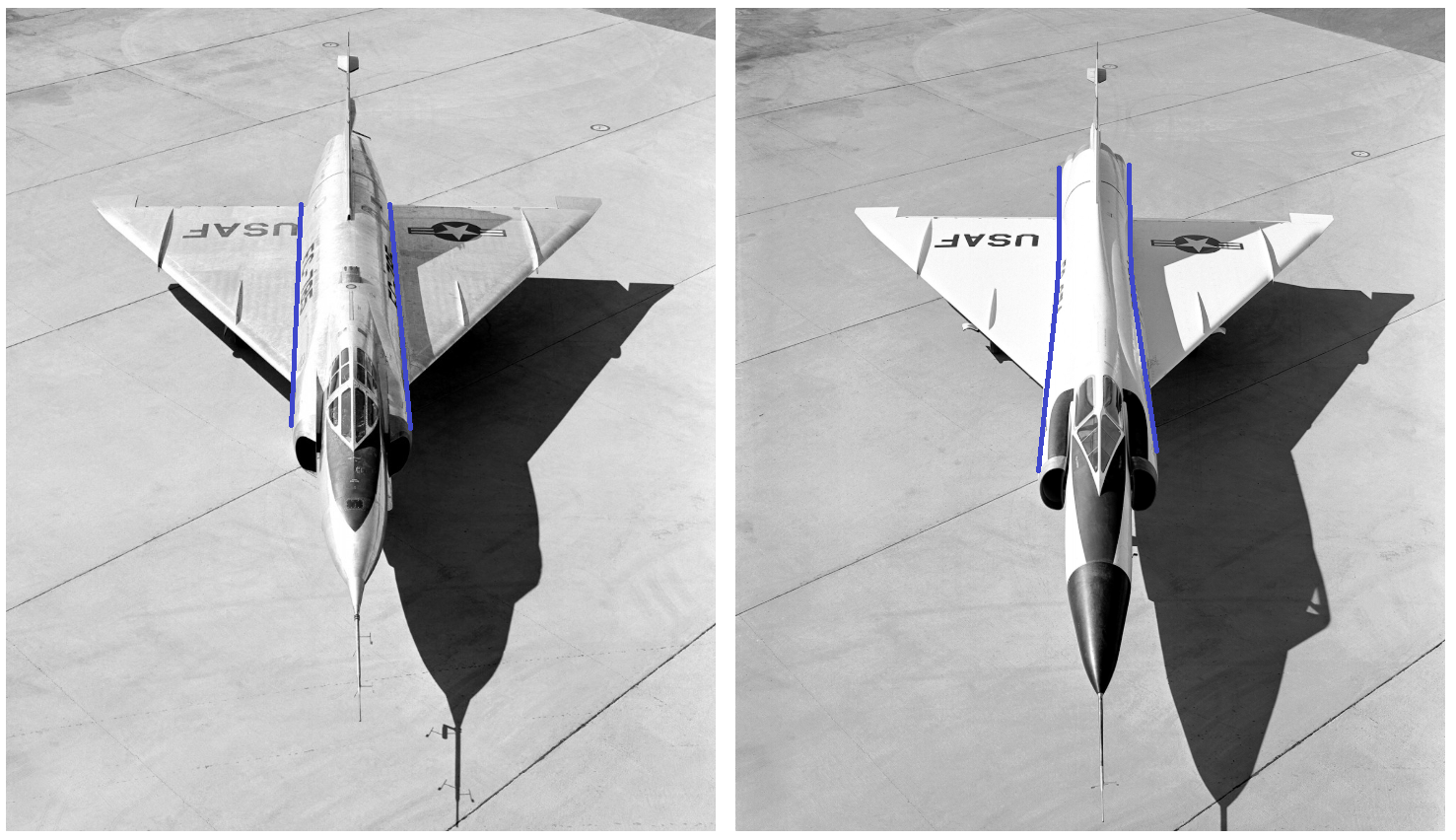

Fuel consumption was not the only cost. Any supersonic aircraft has to be able to do three things: generate enough lift and maneuverability at subsonic speeds where takeoff, landing, and much combat took place, accelerate through the transonic zone as quickly as possible, and operate efficiently at supersonic speeds. Each of these has very different requirements, and Gen2 fighters were being designed in a world without sophisticated modeling of airflows. As a result, the Gen2 fighters tend to share a particular look. They are long and spindly, with small or delta wings. They usually have a pronounced narrowing around the middle of the fuselage, slightly reminiscent of a coke bottle. This narrowing was called area ruling, and came about after it was realized one of the main generators of drag was sharp changes in the cross sectional area of your aircraft. An excellent example of this is the F-102 fighter. Early prototypes unexpectedly failed to achieve supersonic flight. Redesigned, it was able to exceed Mach 1.2.

The F-102 before and after area ruling

This look was imposed by the demands of supersonic flight, and it meant sacrifices in other areas of performance. The small wings meant high take off and landing speeds, which lead to high accident rates. Small control surfaces and high wingloading limited maneuverability. And the desire to limit drag often meant limited weapon carriage, even as we saw the birth of air-to-air missiles.

Missiles & Radar

In the age of the gun, most aircraft gun kills occurred at less than a mile, and the maximum distance a pilot can even see an enemy aircraft is only about 20 miles. At that distance, two planes travelling at 600mph will have one minute to spot each other, and will be in gun range for less than 3 seconds. At supersonic speeds, that time is reduced to almost nothing.

The solutions were missiles and radar. The use of radar to track aircraft began in the 1930s, but early radar sets were far too large to put on planes. By the end of the war, specialized, radar equipped “night fighters” had been developed by all participants, but these were large aircraft, often using light bomber airframes that were no match for fighters during the day. By the 50s fighters had grown and electronics had shrunk, making it possible to equip them on aircraft competitive with day fighters. These radars were still relatively primitive analog devices, but they allowed detection at tens of miles, in far more weather and light conditions than the human eye.

Making use of greater detection ranges required greater effective weapon ranges. Air to air rockets had been used as far back as World War two, and while they could have greater effective ranges than guns, they proved most useful against targets that couldn’t maneuver, like bombers in formation. But while little could be done to improve the range and accuracy of guns, the potential of guided rockets was obvious, and the concept had been experimented with for decades.

When it comes to air-to-air weapons, these experiments first bore reliable fruit in the heat seeking missile. This is perhaps not surprising, given how much heat jet engines produce. These missiles used IR cameras and simple electronics to steer themselves towards the brightest source of heat they could see. LIke the radars, they were primitive. Early models had ranges of a few miles at best, would not work if not fired at the rear of a target, and could often be confused if their target flew by flying towards the sun. Even so, they represented a large increase in range and accuracy over guns. As a result, Gen2 is when missiles became the primary armament of fighter aircraft, with some fighters abandoning guns entirely. Where they were retained, they were a secondary weapon, usually a single, higher rate of fire weapons like the 20mm Vulcan gatling gun replacing the array of cannons found in Gen1

Size

The result of all of this was planes that were much larger. The F-86 had an MTOW below 20,000lbs. Redesigned for supersonic speeds as the F-100, it weighed 35,000lbs. Even the spindly F-104 clocked in at 30,000lbs. This was as large as light bombers during WW2, the B-25 weighed in at 35,000lbs, the Ju-88 was 30,000. The increase in size, again, came with an increase in cost.

Despite the cost, Gen2 saw a decline in flexibility. While fighters had traditionally been well suited to a variety of roles, this is perhaps less true of Gen2 than any other generation of fighter. They were designed to fly high, fast, and in a straight line. When it came to attacking ground targets, reconnaissance, patrol, and other roles, their performance suffered. The god of speed demanded large sacrifices.

1 That’s why modern airliners fly at this speed ⇑

Comments

I feel there should be a word about early jets being unsuitable for naval aviation

"Unsuitable" or not, the McDonnell FH Phantom first flew in January 1945 and entered service in August of 1947; the follow-on F2H Banshee first flew in January 1947 and was in squadron service by March 1949.

A couple of J85s can fix that.

So much so that the only resemblance is the name, it certainly didn't handle similarly.

Weren't those Medium Bombers.

In a piston engine, this reaction is confined to a piston, and the mechanical energy pushes a cylinder that turns a driveshaft to power a propeller.

The confining space is the cylinder, the energy from the ignited fuel pushes the piston which turns the crankshaft.....

Yes, spinning a plane faster and faster tends to greatly harm the efficiency ;-P

(I know what you meant... just found it funny!)

@ike - There was also the British Sea Vampire..

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DeHavillandVampire