Today, we continue reader Michael Tint's series on the history of the jet fighter, cataloging the changes that came with each generation of aircraft. He previously covered generations 1 and 2, the subsonic and early supersonic aircraft.

Gen 3

An F-4 Phantom, the definitive Gen 3 jet fighter

The 1960s saw the emergence of Gen3 fighters, marking the moment electronics ceased to be accessories and became the heart of the aircraft’s design. As radars became mandatory for tracking and radar guided missiles became the primary means of engagement, the fighter demanded more. More internal volume to house powerful radars and electronics, more hardpoints to carry more and bigger missiles, more thrust to keep up the speed, and more fuel to keep it all going. This is the era when the nimble dogfighter of old was replaced by the complex integrated weapons platform.

Abandoning Speed

While Gen3 would prove the first generation of fighters not to see a broad increase in speed, this was not for lack of trying. Faster and higher had been the goal of every generation of fighters before the jet age even began, and many programs for Mach 3+ fighters were launched. Unfortunately, while engines and understanding of aerodynamics had improved greatly, going faster still required geometrically more thrust and fuel. This meant enormous increases in size (to carry the fuel) and thus expense.

The sacrifices this speed required were demonstrated by the one Mach 3+ fighter that entered service in large numbers, the MiG-25. While the MiG-25 could (sort of)1 sustain Mach 3+ flight, it was an enormous aircraft that weighed over 80,000 lbs. It carried 35,000 lbs of fuel internally and 10,000 lbs externally. That is, it carried about as much weight in fuel as an entire, fully loaded F-4, itself one of the larger Gen3 fighters.

A MiG-25. Note how small the canopy is.

In addition to the size, the MiG-25 replicated many of the problems with Gen2 fighters: short engine life, long take off runs, and poor handling at low speeds. Despite its size, it carried a grand total of 4 missiles or 8,800 lbs of payload.

While the Soviets produced the MiG-25 in large numbers despite these flaws, other countries balked at the tradeoffs such speed demanded. Instead, they used improvements in aerodynamics and engine technology to increase range, payload, and maneuverability, eliminating some of the issues that came with Gen2 aircraft while maintaining Mach 2 speed.

This desire to improve handling characteristics led to one of the more unique features of Gen3 fighters, variable sweep (swing) wings. While highly swept wings are a requirement for transonic and supersonic flight, straight wings are much more efficient at low speeds. One solution to this problem was a plane that could change the shape of its wings. Aircraft like the MiG-23 and F-111 had wings that would sweep forward for take-off and low speed maneuvering, or backwards for high speed flight.

Swing-wing planes with wings swept forward and back

These swing wings dramatically improved the aerodynamic performance, but nothing in design is free. Swing wings imposed large costs in complexity and weight. Powerful motors were required to move wings holding up tens of thousands of pounds of fighter operating at multiple Gs, and the center of the aircraft had to be strengthened to deal with multiple wing angles. And movable wings meant that the wings couldn’t be used for stores without complicated swivels to keep them pointing forward as the wing moved. As a result, swing wings would be largely limited to Gen3 fighters.

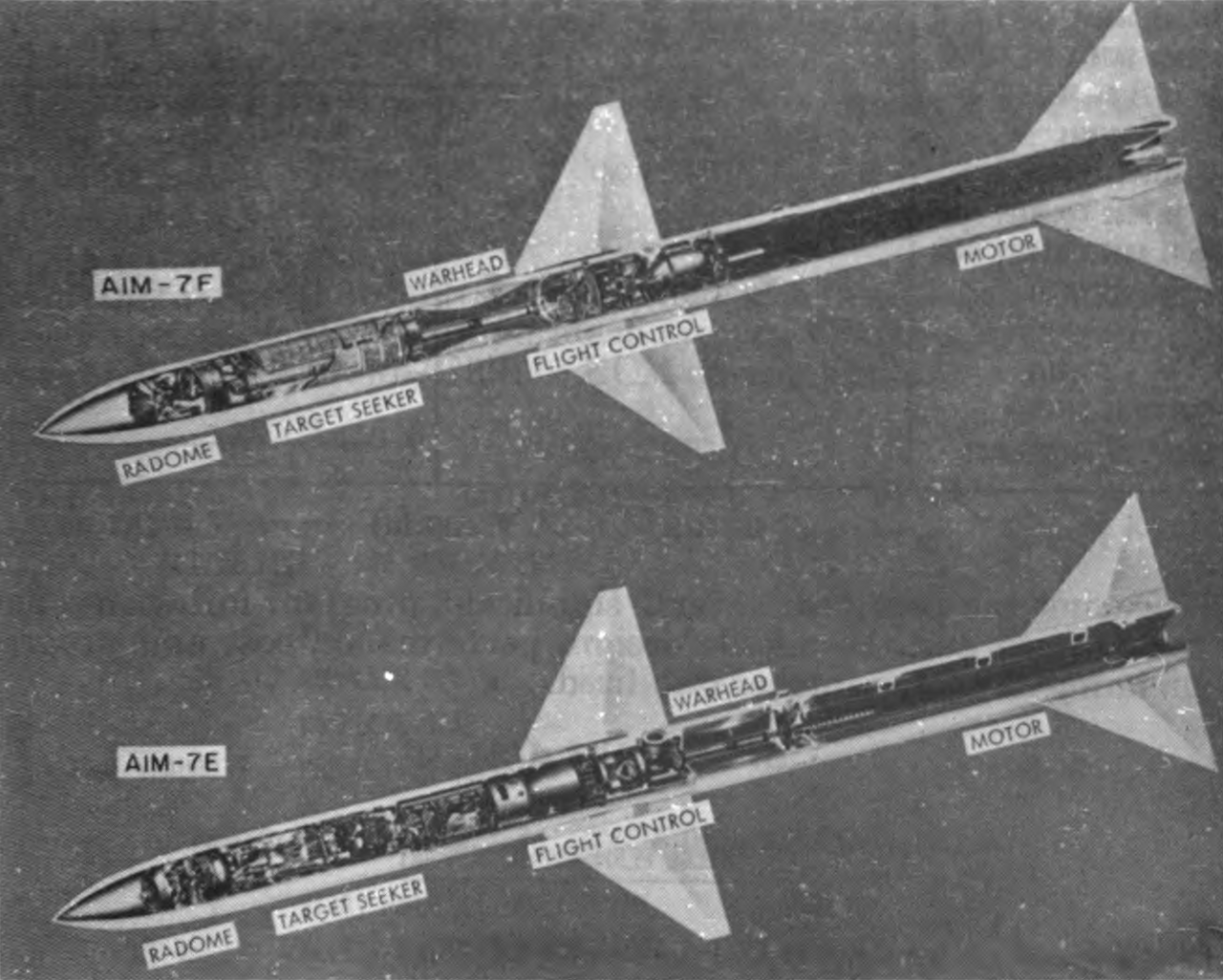

Radar Guided Missiles

While Gen2 fighters relied primarily on heat seeking missiles, Gen3 saw emergence of the radar guided missile as the primary air-to-air weapon. Radar could track targets at any angle, and from much farther away than heat seeking, but emitting and detecting radar waves required much more sophisticated electronics than heat seeking. But while radars were ubiquitous on Gen2 fighters, getting a radar onto a 500 pound missile was a challenge.

Early radar guided missiles “solved” this problem by using command guidance. That is, the missile did not really have a guidance system. Rather, the radar would track the target, and communicate instructions to the missile about what direction to fly in to intercept it. Unfortunately, the possible range of such a system was severely limited by the physics of radars.

Radar works by sending out pulses of microwave radiation that hit a target and bounce back to the receiver. The strength of these pulses drops off exponentially with distance traveled, and because the pulse has to travel to the target and back, they suffer this effect twice. For example, take a radar with a notional 10,000 units of strength. Leaving out constants to keep the math simple, once the signal it emits travels 10 miles to the target, it will be down to a strength of 100. By the time it gets back to emitting radar, the strength will be down to 1. At 15 miles, the return signal has a strength of only .2. That is, a 50% increase in range requires a 5x increase in power. As a result, the range of command guidance was intrinsically limited, and it was not much used for air-to-air weapons.

By the 1960s, two things had changed. First, aircraft were larger and could carry more powerful radars with better signal processing. Second, electronics miniaturization made it possible to fit radar receivers in missiles small enough to be carried by fighters. These could not emit radar waves, but they could detect them, and that made possible the Semi-Active Radar Homing missile (SARH).

SARH missiles function by having the attacker illuminate the target with a radar beam and fire the missile. The missile will initially be guided by instructions from the attacker, but as the missile gets closer to the target, the return its receiver sees will grow rapidly in strength, allowing the missile to guide itself to the target.

For example, go back to our notional 10,000 strength radar. At 15 miles, the attacker gets a return signal strength of .2. With a command guided missile, that would be as good as things get. If the target moves further away or tries any sort of jamming, the signal will only get weaker, possibly so weak that the target escapes. As the missile closes on the target, the signal will get stronger. At ten miles, it will have a strength of .44. At five miles a strength of 1.8, nearly ten times as strong as what the attacker sees. Even with the primitive signal processing possible on a small missile, the signal is vastly harder to jam, spoof, or evade.

As a result, semi-active missiles increased the range of air-to-air combat. For the first time, it was possible to detect and kill targets beyond the range of the Mk1 eyeball. While early missiles sometimes struggled with reliability and problems of identification, this transition marked a new era in air-to-air combat.

Electronics

Gen3 fighters saw large increases in the sophistication and number of their electronic systems. First and foremost of these was radar. As discussed earlier, radars were growing dramatically in power and sophistication. While far more powerful than their predecessors, they were still mostly analog devices with minimal automation. Getting the most out of them required constant tweaking and a human touch.

Visibility from the F-4's cockpit is famously bad

Of course, revolution begets counterrevolution, and the missile and radar revolutions were no different. As these systems became common, so did attempts to counteract them. As a result Gen3 saw the emergence of now familiar panoply of aircraft combat systems: radar warning receivers (RWR) to warn of being targeted, electronic countermeasures (ECM) to confuse enemy radar, chaff and flares to confuse missiles, and more. In addition, the era saw increasingly sophisticated navigation, communication, Identify Friend or Foe (IFF) and other systems, even targeting pods for the first precision guided weapons.

Managing all of these systems became difficult for pilots to handle on their own. The result was the traditionally lonely fighter pilot being joined by a comrade. Called WSO for Weapon System Operator, RIO for Radar Intercept Officer, or generically GIB for Guy In Back, these flight officers were necessary to manage the increasing complexity of these aircraft.

More crew wasn’t the only need, more aircraft types were also required. These systems took up weight and space. It simply wasn’t possible to build a single plane with a fully capable bomb computer, radar, or electronic warfare system and already crammed cockpits of Gen3 fighters often didn’t have room for yet another gadget, even with the addition of the GIB.

Thus, this era saw a flowering of specialized types that took the basic airframe of a fighter and adapted its equipment for specialized roles like ground attack, Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) reconnaissance, electronic attack (EA)

Gen 4

An F-16, probably the standard Gen 4 fighter

Gen4 fighters began to emerge in the mid-1970s, Observant readers will note that the time gap between generations has widened at each stage; as complexity increased, so did development time.

If Gen3 was defined by "more is more" then Gen4 was defined by digitalization. Not that fighters didn't get bigger, they did, but this era marked a fundamental pivot in design philosophy: the transition of the fighter from a collection of bolt-on components into a cohesive digital system.

The result was a generation of aircraft that were smarter and more efficient, doing what Gen3 did, but better. Chief changes were the turbofan engine, the embrace of relaxed stability and fly-by-wire, the birth of true multi-role capability, and a tremendous leap forward in electronic sophistication.

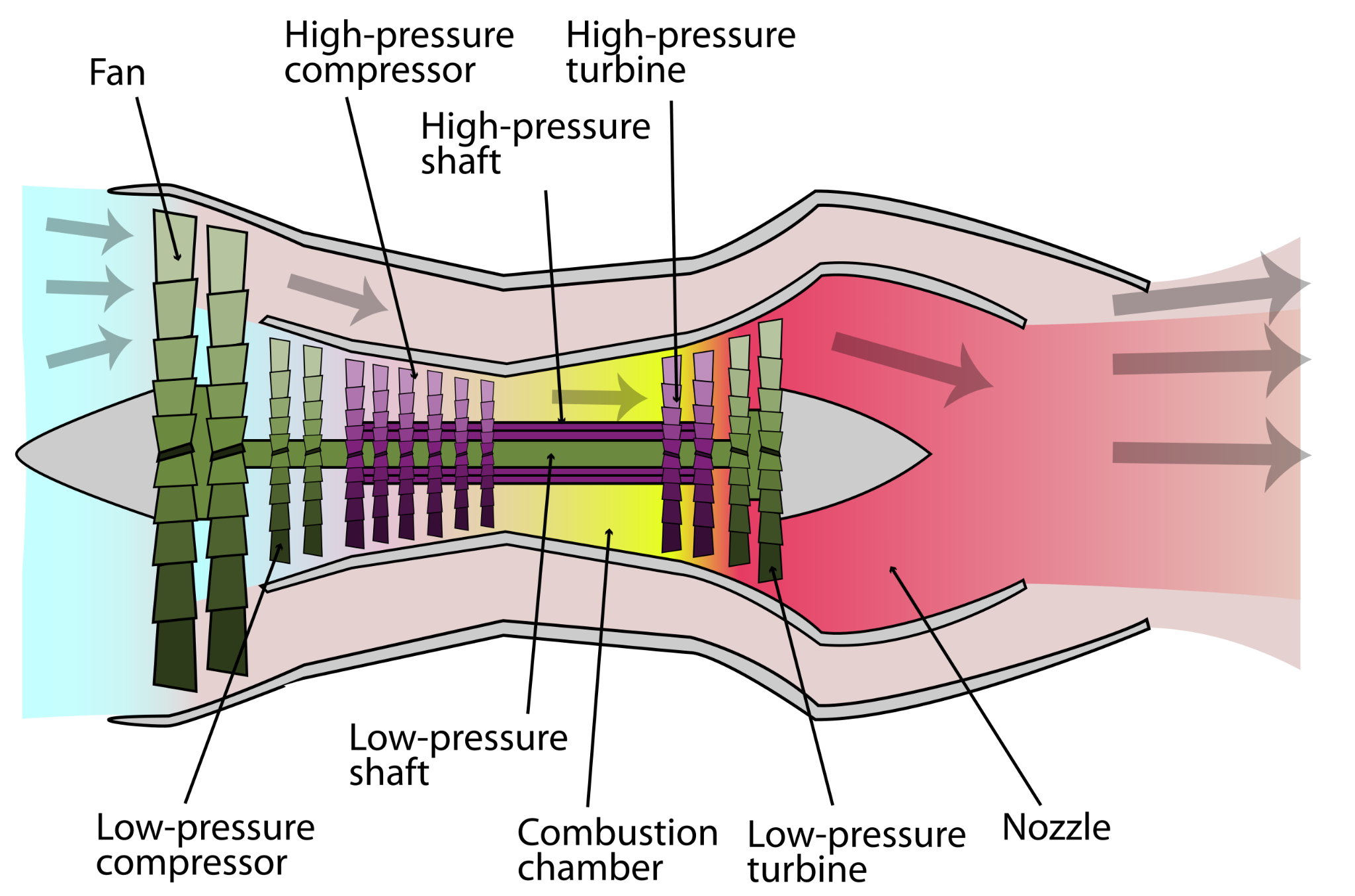

Turbofans

How much thrust an engine produces is determined primarily by two factors, the mass of air moved and how much acceleration is imparted to that air. While both options work, at any given speed, moving more air is more efficient than making the air go faster.

A turbofan engine

A turbofan engine takes a turbojet engine and adds a large fan and ducting to hold it. This fan moves a large amount of air, most of which does not flow into the turbojet, but around it, increasing the efficiency of the engine.

Unfortunately while the fan produced a great deal of thrust, it also produced a lot of drag, especially as speed increased. So while turbofan engines rapidly took over the commercial airline industry in the 60s, it took longer to work out effective supersonic turbofans. However, they gave much greater performance. Not when it came to top speed - Gen4 fighters would see little meaningful improvement there, but far more efficient operation. Gen4 fighters would have longer range, better power to weight ratios, and lower fuel fractions than their predecessors. And because they had FADEC (Full Authority Digital Engine Control), they had much better throttling and far more resistance to the compressor stalls that plagued their predecessors.

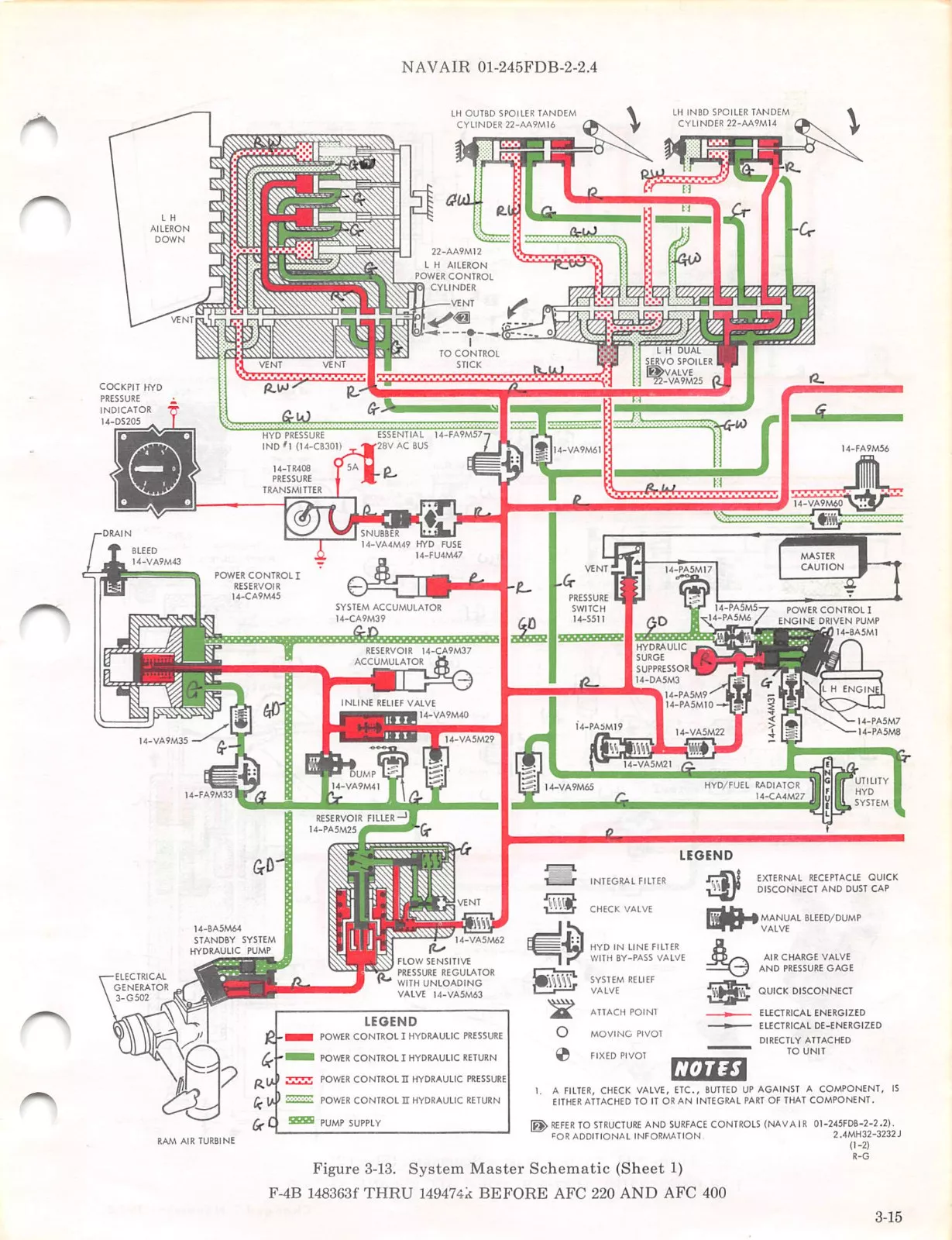

Fly-by-Wire

In early aircraft, control surfaces were controlled by rods or wires linked directly to cockpit controls. In small, slow aircraft, the strength of the human hand or foot was sufficient to control a plane. But as planes grew heavier and faster, the amount of physical force needed to move them around grew rapidly. This was compounded by the fact that a rapidly maneuvering fighter will experience multiple Gs, further multiplying the effort required.

Some of the hydraulics on an F-4

As a result, by World War Two fighters were being equipped with hydraulic and pneumatic systems that either augmented the mechanical force coming from the pilot or replaced it entirely. While highly highly reliable, these systems were heavy and complex, and they still depended on a physical connection between the cockpit and the control surfaces. As jet fighters grew these systems only got more elaborate, with commensurate increases in size, cost and weight.

By Gen4,modern computing had made it possible to replace this complex analog system with “fly-by-wire”, meaning that instead of physical linkages, control inputs were transmitted electronically to a flight computer which interpreted them and passed instructions along to the control surfaces, again, electronically.

The most obvious advantage of such a system was the savings in weight, complexity, and maintenance. A fighter could easily have a dozen or more control surfaces, each of which needed to be able to move on its own, along with backups. These took up considerable internal volume and weight and could be a nightmare to maintain.

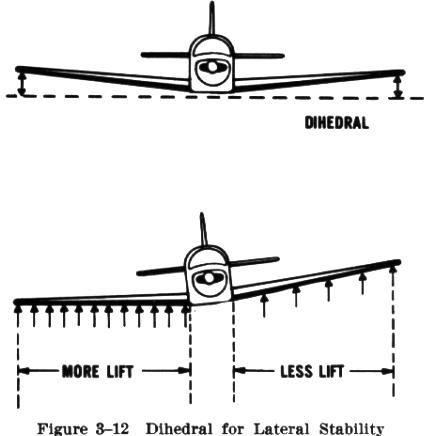

The more subtle advantage, though, was that a digital system could do more than just transmit the pilots instructions, it could interpret the pilot’s will and make it possible to reduce the amount of stability required in an airframe.

Stability is the tendency of an aircraft to keep doing what it’s currently doing. For example, most airliners are designed with wings that aren’t perfectly flat, but dihedral, tilted slightly up. This is because when an aircraft with a dihedral wing starts to roll, the descending wing will flatten, which makes it generate more lift, which counteracts the roll. The more you roll, the more the plane will resist rolling,so the plane is highly stable. Reverse the situation with an anhedral (tilted down) wing and you get the reverse, the more you roll the more the plane will want to roll

Dihedral wings

Stability is great for airliners, but for fighter jets that need to maneuver rapidly, too much is undesirable. An unstable aircraft is very maneuverable but also incredibly dangerous to fly, because the slightest mistake could send the plane spiraling out of control. With fly-by-wire, though, digital flight controls could take the measurements and make the hundreds of adjustments per second needed to keep less stable aircraft flying steadily, allowing for aircraft that were far more maneuverable than ever before.

Multi-Role Electronics

The F/A-18 fighter was originally imagined as two different aircraft, the F-18 and A-18. These shared an airframe, but would have different avionics suites. The former was to have the radars and displays for air-to-air missions, the latter those for ground attack. And, in Gen3, that made sense. While fighters have always had some ability to perform multiple roles, the demands of Gen3 electronics required specialization to achieve peak performance at any particular task, and the difference between them would have been large enough to warrant two designations.

Gen4, though, reversed the specialization trend dramatically. Before the end of their development, the F-18 and the A-18 were merged into a single aircraft - a change made possible by digital electronics. Massive improvements in processing power reduced the weight of electronics, allowing for general purpose digital computers in place of purpose built machines. They also dramatically improved the sophistication of radar signal processing, which allowed the replacement of multiple specialized radars with fewer, more powerful systems capable of multiple modes of operation. And as displays got better, they could, again, become general purpose, switching between views as needed instead of being specialized for a single purpose. And since they were computer controlled, being upgraded to handle additional weapons and modes was a question mostly of software and wiring, not hardware.

In practice, this opened up a world of capability. The F-15 design team used “Not a pound for air-to-ground” as a slogan. They focused on building the best possible air-to-air with no sacrifices for any other mission. Yet the aircraft they produced has proven excellent at air-to-ground roles, and this was not an isolated story. The F-14, F-16, Typhoon and more began life primarily as air-to-air platforms. All yet proved upgradeable for ground attack in ways that simply had not been possible in previous generations. Combined with precision guided munitions (see below) this made for a huge increase in effective air power. A force of 20 F/A-18s was worth at least as much as a mixed force of 30 F-18s and A-18s.

Visibility from the F-15's cockpit is famously good

There were also more subtle benefits. By Gen3, aircraft cockpits had grown incredibly complicated, with hundreds of dials, switches, and gauges. These were necessary due to the limited flexibility of Gen3 electronics, but imposed serious burdens on the pilots in terms of difficulty of operation and limited visibility. This could cause real problems in combat, perhaps most infamously with the terrible design of the F-4’s missile selection switches. These were hard to reach with your hands, easy to accidentally reach with your knees, relied on audio signals (in a roaring cockpit) to indicate status, and could easily disable missiles if handled improperly.

Frustrations with Gen3 saw Gen4 designers make serious efforts to reduce pilot load and increase visibility, much of which were made possible by better electronics. Heads up displays and multimode screens reduced the number of things the pilot needed to look at, while improved automation and interface design reduced how much work was needed to operate the plane.

Active Missile Guidance

Improved electronics also meant that Gen4 fighters could see farther than ever. They were increasingly designed around ever more powerful radars, with large antennas, and sophisticated signal processing that allowed them to distinguish targets from ground clutter and each other. While Gen3 fighters were theoretically capable of firing at targets beyond visual range (BVR), in practice they were often limited by the need to visually identify targets before firing. Gen4 radars could not just see targets much further away, their signal processing was sophisticated enough to positively identify these targets, and verify what they were looking at. Ability to see farther meant a desire to shoot farther, but the tyranny of the radar equation remained.

Phoenix, the first ARH missile, was very large

The solution was the Active Radar Homing (ARH) missile. Like SARH missiles, these would initially be guided in the direction of their target by the firing aircraft, but where SARH missiles only have a radar receiver, the ARH had a complete miniature radar system that both transmits and receives signals. This radar would be far smaller and less powerful than the one on the fighter, but because the radar beam did not have to travel all the way from the fighter to the target and then bounce back to the missile, it would see a much stronger return at long ranges.

Going back to the example, if our notional 10,000 strength radar paints a target 15 miles away, a SARH missile 5 miles from it sees a return of 1.8. Double the distance of the aircraft to 30 miles and that return drops to .44, a quarter as strong. By contrast, at 5 miles from the target, an ARH with a radar of only 500 strength will see a return of .8, no matter how far away the shooter is.

Active homing was not possible with Gen3 electronics. It took digital electronics to miniaturize radars enough to make active homing feasible. Once they arrived, though, they revolutionized fighter combat. Missile ranges rose dramatically, from 20-30 miles to well over 50, with some especially large missiles capable of hitting targets at over 100 miles. Combined with the improved signal processing BVR combat became the norm, not the exception.

Second, ARH missiles were fire-and-forget weapons. SARH required that the firing fighter lock on to the target and hold that lock until the missile hit. This meant that if the target could maneuver out of the vision of the attacker’s radar, the lock would break and the missile would miss. Keeping the lock would also limit the attacker’s evasive options if counterattacked. And as RWR devices increased in sophistication, it could even reveal the shooter’s location to the target. By contrast, once an ARH was near its target, the lock shooter’s lock was no longer necessary, leaving the shooter to maneuver freely.

Precision Guided Munitions

It can be argued that the Precision Guided Munition (PGM) has done more to transform air power than any technology since heavier than air flight itself. While bombing targets from the air is a very obvious idea, it’s never been easy. The first recorded bombing of a target from the air took place in 1911 when an Italian aviator named Giulio Gavotti threw three or four grenades on a Turkish camp. His results set the tone for the next several decades of air-to-ground warfare: he destroyed nothing, killed no one, and yet still managed to cause an international incident.

The accuracy of air-to-ground weapons can be measured by the circular error probable (CEP). This is defined as a circle such that if you drop the munition, it will land in the circle half of the time. Gavotti failed to hit a target the size of a camp while flying at a few hundred feet in the air at less than 80 miles an hour, and the problem would only get harder as planes flew higher and faster. During World War Two, the CEP of bombers could be measured in miles, sometimes struggling to hit entire cities. Bombing computers, improved navigation techniques, and inertial guidance improved this somewhat over time, but the CEP of bombs from Gen3 fighters was still measured in tens to hundreds of meters in what amounted to dive bombing attacks, meaning targets needed to be attacked by multiple aircraft to ensure their destruction and some targets could not reliably be attacked at all.

The Thanh Hoa Bridge

Precision Guided Munitions (PGMs) were first used during the Vietnam War, most famously to destroy the Thanh Hoa Bridge, a target which had resisted several hundred previous sorties. Laser guided bombs were soon joined by bombs guided by GPS signals, television, and infrared, all of which only got cheaper and more accurate with time.

Being able to drop bombs from far greater ranges and altitudes utterly transformed air-to-ground warfare, because it doesn’t just mean the need for fewer bombs to ensure a hit. Being able to count on direct hits meant that smaller weapons could be carried, allowing more targets to be struck. Attack from altitude and distance meant bombing was far safer, with fewer aircraft losses and much less need to use additional aircraft for escort and SEAD missions, freeing up those aircraft to perform strikes of their own. Each of these benefits multiplied the other, making a Gen4 fighter force orders of magnitude more lethal to ground targets than Gen3. As PGMs proliferated, strike planners moved from asking “How many sorties do I need to destroy this target?” to “How many targets can this sortie destroy?”

1 The MiG-25 could fly faster than Mach 3, but doing so would effectively destroy the engines. In practice it was limited to around Mach 2.8. ⇑

Comments

Calling the Italo-Turkish War an international incident is like calling the Sun a large lightbulb...

@Emilio

The war was already ongoing, so I presume "international incident" refers to the Ottoman accusation that the attack was a war crime.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GiulioGavotti#citenote-Flight100_59-1

Re: the Thanh Hoa Bridge (and indeed other bridges in Vietnam), I have read that a major reason for air attack being so ineffective against them was that political authority decreed that they could only be attacked from the perpendicular, along the river(s); this made the bridge(s) almost impossible to hit. Hits would have been much easier to achieve had the aircraft been allowed to attack from along the road(s), but the overwhelming concern was that Soviet advisors might be manning GBAD positions near the feet of the bridge(s) and the inevitable "overs" and "unders" (which made it so much more difficult to bomb the bridge(s) from the perpendicular) would have endangered said advisors.

I've heard that one of the major factors in the decline of variable-sweep wings is that, in addition to the complexity and weight penalties, fly-by-wire made them obsolete. That is, with a computer helping to keep the aircraft stable, aircraft could be designed with smaller wings optimized for high speed flight, and the resultant stability and controllability penalty at low speed could be canceled out with software (the flight control system) rather than hardware (actually moving the wings).

Is this true to any extent or is it more of a just-so story?

@quanticle

I think that makes sense, at least for fighters - swept wings also have lower aerodynamic efficiency in terms of lift (lower aspect ratio and more losses over the wingtips), but fighters/fighter-bombers have enough thrust that it’s a secondary consideration, at least for short periods. For longer missions the aerodynamic losses are still problematic.

I'm not sure that's true. For one thing, the F-15 is neither swing-wing nor fly-by-wire, and for another, while FBW can help with control and stability, it doesn't really solve the problem of "I need to generate X lift at fairly low speed to avoid falling out of the sky when landing", and I suspect that dominates.

In that case, was it that improvements in engines allowed planes to reach high speeds while having large enough wings that landing speeds weren't excessively high? I'm thinking about the F-104, and I'm wondering why, for example, the F-16 didn't turn out the same way. The F-104 (and its Soviet counterpart, the MiG-21) have reputations for being difficult to land because their relatively small wings require a relatively high landing speed, which gives the pilot less time to make adjustments if anything should go wrong. The F-16, on the other hand, has a reputation for being a fairly forgiving plane to fly (well, forgiving by the standards of fighters, at any rate). And yet they both have top speeds of around Mach 2. So I guess I'm wondering how the F-16 managed to reach close to the same top speed while not sacrificing everything else in service of that goal, as the F-104 pretty much did.

Per wiki (so add salt to taste) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LockheedF-104Starfighter#Specifications_(F-104G)

Length: 54 ft 8 in (16.66 m) Wingspan: 21 ft 9 in (6.63 m) Height: 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) Wing area: 196.1 sq ft (18.22 m2)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GeneralDynamicsF-16FightingFalcon#Specifications(F-16CBlock50and_52)

Length: 49 ft 5 in (15.06 m) Wingspan: 32 ft 8 in (9.96 m) Height: 16 ft (4.9 m) Wing area: 300 sq ft (28 m2)

That seems like a lot more wing on the -16 than on the -104

Less than you might think. The parameter we should care about here is wing loading and the F-104 has a wing loading of 148 lb/sqft at MTOW, while the F-16's is 141 per those numbers. That said, the F-104 is aerodynamically very simple, while the F-16 isn't, and I suspect that there's a lot of area generating lift on the F-16 that doesn't show up in a single wing area number.

Wing loading is definitely a less useful metric than it used to be. All the gen4 plus aircraft I know about have lifting bodies to a degree.

My understanding is that if you put f104 level avionics in an f16, it would basically be unflyable, but the phrase F104 level avionics covers a lot. The f16 has a better cockpit layout (I've not heard that the 104 is especially bad in this regard but a lot of effort went into making f16 good), it has a way more reliable engine with a FADEC that keeps you from doing something stupid, way more thrust to weight so you can recover if you do do something stupid, better instruments, and more in addition to fly by wire.

They were able to get by without swing wings because of all the gen4 stuff. turbofan engines gave more thrust, particularly at low speeds, which helped with takeoff performance. They were also much more fuel efficient, which was important since a lot of the push for swing wings was to improve loiter times.

Better computers were able to do aerodynamic modeling on more complex shapes to get aircraft shapes to get lifting bodies or other benefits, and fly by wire kept it all straight and level.

Of course, you could apply all that to aircraft with swing wings and get even more. Grumman pitched various evolutions of the f14, and they all had insane performance. what killed of the swing was cost. Not just the initial cost, but they were all maintenence nightmares. That was true even of the f14, which was designed very much in the spirit of "let's try the f111 again, but good this time." You needed swing wings to do certain things in gen3, but the juice wasn't worth the squeeze by gen4.

The problem was not with the F-111 per se, but with the navel version.

Both USAF and RAAF were quite fond of it.

The only problem USAF ever had with the F-111 was that they were not sure what its top speed was...

Emilio:

Even then that only came about because the Navy changed their minds about what they wanted.

But they did have other issues:

Basically everything I know about Gen4+ fighters comes from: The Falcon 3 ("The Definitive Fighting Falcon Simulator") manual Playing Falcon 3 Reading Naval Gazing (blog, comments, discord)

with a small appendix from having played the Microprose F-15 Strike Eagle game (obtained while wearing an eyepatch, so I couldn't read the manual)