The story of the ironclad in battle takes us next to the Pacific,1 and the monitor Huascar. Built by Laird Brothers of Birkenhead for Peru, she was commissioned in 1866, slightly too late for the war she'd been ordered to fight. 1,870 tons, 220 ft long, and mounting 2 10" guns in a single turret, she was a reasonably powerful vessel for the day, although she was essentially a coastal defense ship. The belt ranged from 2.5" to 4.5", and her maximum speed was 12 kts.

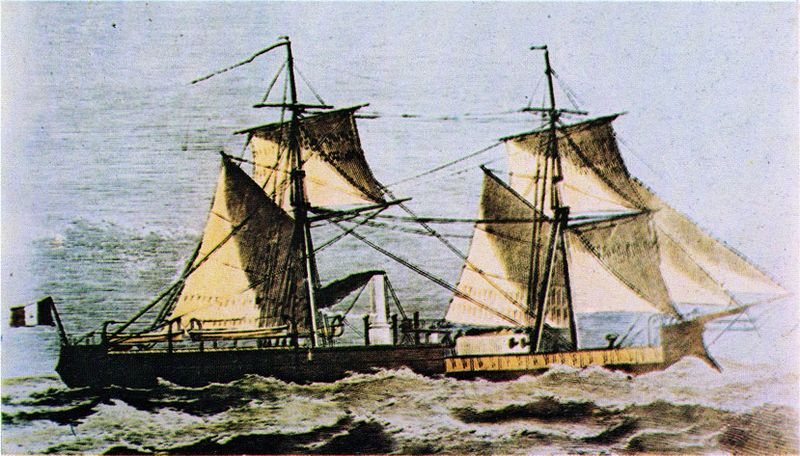

Huascar as completed

Her first decade was quiet, but in 1877, a civil war broke out, and Huascar was seized by rebels, who began to run her up and down the coast, extorting "contributions" from coastal cities. This irritated several of Peru's trading partners, most notably the British. In response, they dispatched two of their ships, the unarmored cruisers Shah and Amethyst, to put a stop to it. They encountered Huascar on May 29th, 1877. The resulting battle was indecisive. Peruvian gunnery was poor, while the 60 to 70 hits the British made on Huascar did little damage, although their effectiveness was limited by their inability to close the range against their armored opponent. The only effective hit was one shell that pierced the 3.5" plate near Huascar’s stern.

The Battle of Pacocha

This battle was also notable as the first ever use of the Whitehead torpedo2 in combat. Huascar had closed with Shah as if to ram, and Shah fired a torpedo. Unfortunately, torpedoes of the day were so short-ranged that it was ineffective.3

Shortly after the torpedo missed, Huascar’s colors were shot away, and there was a lull while the British thought she might have surrendered. The ship's crew hoisted a second flag, and the battle resumed. However, Huascar was close to shore, and fear of hitting the town of Ylo stayed the British fire until dark, when Huascar slipped away. She surrendered to government forces the next day, and the rebellion flickered out.

Huascar in 1879

Two years later, another war broke out, between Chile and an alliance of Peru and Bolivia, over control of an area rich in guano on the Pacific coast.4 The fate of a piece of the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on Earth, would be decided by what happened at sea. The Bolivians didn't have a navy, while the Peruvian navy was heavily outmatched by the Chilean. Theoretically, they had four ironclads, the seagoing Huascar and Independencia, and the coastal Manco Cápac and Atahualpa, while the Chileans only had Cochrane and Blanco Encalada. However, the Chilean ships were the better part of a decade newer, and significantly better armed and armored, while the Peruvian coastal monitors had been built for the US during the Civil War and were slow and unseaworthy. The only advantage the Peruvians had was that Chile lacked a drydock in which to clean the hulls of their ironclads, meaning that Huascar and Independencia had a speed advantage.

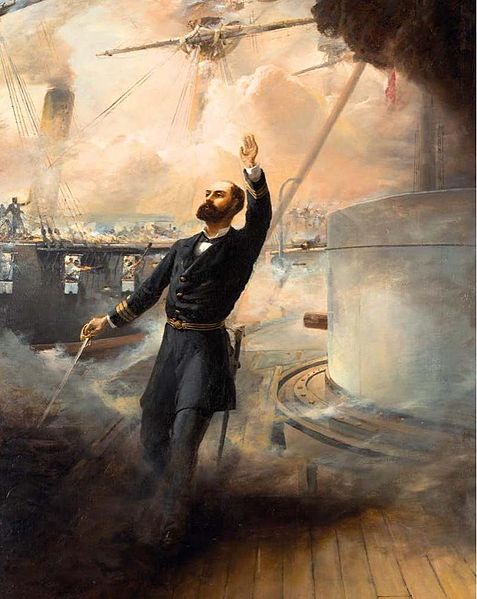

Miguel Grau

Huascar was under the command of Admiral Miguel Grau, who had previously been her commander between 1868 and 1876. He had returned to command her and the Peruvian Navy as a whole, with a plan for Huascar and the rest of the fast Peruvian ships to raid the Chilean coast, denying them control of the sea.

Arturo Prat

The first major naval battle of the war was fought off the Peruvian port of Iquique, which the Chileans had been blockading. Huascar and Independencia fell on the blockading Chilean ships, the wooden Esmeralda and Covadonga. Despite being heavily outmatched, Esmeralda's captain, Arturo Prat, chose to fight. Huascar attacked Esmeralda, while Independencia engaged Covadonga. Prat took Esmeralda in close to Iquique, where shallow water prevented Huascar from closing in. Eventually, the Peruvian forces ashore assembled artillery and drove Esmeralda back into deeper water. A boiler then burst,5 limiting the Chilean ship to only 3 knots.

Huascar and Esmeralda in action off Iquique

The battle was an interesting contrast. Chilean gunnery was excellent, but their guns, the heaviest a 40-pounder, were ineffective. The Peruvians only fired 40 rounds from the 10" guns during the four-hour engagement, and only got one hit, which destroyed Esmeralda’s engines and killed her engineers6. Grau then ordered Huascar to ram, although the attack was executed poorly, and little damage was done. Prat attempted to board the ironclad, but only one man followed him. Grau called on them to surrender, but Prat refused, and was shot down.

Prat's death aboard Huascar

Grau rammed again, and the only difference from the previous attack was that this time a dozen Chileans managed to get aboard Huascar. They were no more successful than Prat had been in taking the ironclad. However, the combined rammings, as well as the few hits, had disabled Esmeralda, flooding her magazine and leaving no ammunition for her guns. Huascar’s third ramming was successful, sending Esmeralda to the bottom. Only 63 of her crew of 200 survived.

Esmeralda beginning to sink

Prat became a national hero in Chile. Four warships and the Chilean Naval Academy were named after him. Grau became known as "The Gentleman of the Seas" for his conduct. Immediately after the battle, he made sure that all of the survivors of Esmeralda were rescued. Later, he returned Prat's body, and his personal effects, to Prat's widow, along with a letter of condolences. During a later raid, he made sure to give the crew of a merchant ship a chance to evacuate before destroying it, despite the proximity of Chilean pursuit. He was celebrated in Chile for this, as much as in Peru.

This was not the end of Huascar’s career, a tale I'll tell next time.

2 The Whitehead torpedo was the first practical self-propelled torpedo, and the ancestor of the modern torpedo. ⇑

3 I'm not sure of the exact model of torpedo used in the battle, but the most advanced Whitehead at the time had a range of 800 yards. ⇑

4 This is sort of South American military history in a nutshell. A major war, fought over bird poop. It wasn't the first one, either. ⇑

5 This was a fairly common problem with powerplants of the era ⇑

6 Probably. There may have been more hits, or hits from Huascar’s unarmored guns. My source is unclear. ⇑

Recent Comments