This is the first half of a two-part effortpost on SCUBA1 diving originally posted at Data Secrets Lox by John Schilling. This part is devoted to the basic principles of scuba diving and the hobby of recreational diving, while the second half will cover more advanced technical diving, and professional or military diving activities.

Diving is not actually all that difficult, at the most basic recreational level. You’re not going to suffocate or run out of air – there’s plenty of that no more than twenty meters (65’) away, and you’re buoyant enough that if you drop your weight belt you’ll float to the surface in seconds. You shouldn’t be diving deep enough or long enough that even an emergency ascent will give you “the bends”. And the sharks aren’t going to eat you.

But it absolutely does require training, about two full weekends’ worth, because there are some ways to kill yourself very quickly if you do something stupid and the not-stupid things, while easy to describe, are neither obvious nor instinctual. Your first few dives need to be with an expert watching closely to make sure you don’t do anything stupid. At that point you scan safely spend an hour or so looking at already-known Neat Stuff down to about twenty meters, in calm open water in daylight. Highly recommended if you live or vacation anywhere with good diving, because there’s a lot of neat stuff to see. There are several agencies that certify recreational divers; PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) is probably the largest, but the others have their fans (and occasional holy wars). Without a certification card from one of them, nobody will rent you dive gear, nobody will fill your air tanks, and nobody will let you on board their dive boats.

Neat stuff: Fish in more sizes, shapes, and colors than you thought possible. Also rays, eels, and sharks large and small. The multitude of invertebrates crawling on the sea floor do nothing for me, but other people find them fascinating (and even I have to admit the occasional octopus is kind of cool). Coral reefs and kelp forests. An eerie landscape of sand and rock in exotic forms, often crusted in marine life. Shipwrecks if you know where to find them, and many of the better ones are mapped. Even a couple of battleships and aircraft carriers, though they’ll require more advanced training. Other underwater infrastructure; offshore oil rigs are interesting both for the engineering and the marine life that calls them home. And playful marine mammals, including but not limited to other divers.

Before we get to how to do that, let’s talk about the things that will kill you if you’re stupid.

First, barotrauma. You must never, ever try to hold your breath while scuba diving. Not even for a few seconds. Most of your body is made of incompressible substances that easily adapt to local pressure changes. Exposed to say 100 psi, body tissues compress infinitesimally to reach an equilibrium 100 psi everywhere – no pressure differential, no problem, not even any discomfort. If you feel anything squeezing or compressing you, that’s your wetsuit being too tight. Except for the one obvious thing, which is the air in your lungs. Compressing the air in your lungs isn’t actually a problem. Expanding the air in your lungs, is a big problem. If you don’t let escape, it will insist on filling your chest cavity – hundreds of pounds of force smearing your lungs into a thin layer on your chest wall. And yes, your epiglottis is strong enough to lock down your lungs against enough pressure to kill you. Ascending even five feet above the depth where you last inhaled, while trying to hold your breath, can be lethal.

The air in your inner ear won’t kill you, but it can rupture your eardrums almost as easily as your lungs, so you’ll need to learn how to equalize pressure there.

Decompression sickness2 might kill you; it takes extreme carelessness to pull that off with basic open-water recreational diving, but more advanced recreational and especially technical diving make it a more serious issue. If you’re breathing high-pressure air, the inert nitrogen dissolves into your blood. When you come back to a low-pressure environment, the nitrogen comes out of solution in roughly the way carbon dioxide comes out of solution when you open a can of soda. You really don’t want your blood to be as fizzy as a freshly-opened can of soda. There are four ways to avoid that: don’t go too deep, don’t stay down too long, don’t come up too quickly (and maybe stop for a while at an intermediate depth), and consider breathing something that isn’t 80% nitrogen.

The mathematics of this are rather complex, in part because nitrogen doesn’t just dissolve into your blood but then diffuses into other body tissues – at different rates, and then comes out at different rates as well. You can go deep, come up moderately slowly, feel just fine with your nitrogen-free blood flowing through your veins, and then have problems half an hour later as the nitrogen starts coming out of your body fat. Fortunately, smart people with computers have done this math so you don’t have to. Some general rules of thumb: At 10 meters, you won’t have to worry about this within the context of a typical recreational dive. 20 meters, you’ve got about an hour of safe diving. At 40 meters, your safe bottom time is down to maybe ten minutes – and a five-minute stop at 5 meters is highly recommended.

Nitrogen narcosis won’t kill you directly, but it will make you stupid and that makes it easier for everything else on this list to kill you. There are some neurobiologists with a vague notion of how this actually works, but the bottom line is that chemically inert gasses somehow act as narcotics in proportion to molecular weight and partial pressure. For nitrogen, this is roughly equivalent to one martini per ten meters after the first twenty meters.

Basically, at the limits of recreation you will always be DWI (diving while intoxicated), and that’s tolerable in something as slow-paced as recreational diving but you need to keep it in mind. Or you can get yourself killed by going deeper than you planned, because e.g. the very beautiful fish you were chasing pulled your attention away from your depth gauge.

Getting trapped or tangled at the bottom can be deadly for the obvious reason – that endless supply of fresh air close above becomes unreachable - and it’s why basic recreational diving is only done in open water. Things like kelp forests and abandoned fishing lines can be an entanglement hazard, and things like caves and shipwrecks are right out without advanced training.

And then there’s all the sharp, jagged, sometimes venomous things that look enticingly pretty and demand close inspection. Sharks mostly aren’t a problem here; they generally don’t see divers as food. Venomous invertebrates of a hundred different kinds, are too stupid to know the difference. Coral, is just plain sharp. Shipwrecks that haven’t been pre-safed for diving, can be even sharper.

Finally, it is possible to be simply lost at sea if fast currents or poor navigation took you too far from your recovery boat and the lookouts were careless. That’s rare, but not unheard of. But currents are a serious issue in any case; anything more than about two knots and you’re going to be overpowered – it’s just that dive boat captains can almost always figure out where you wound up so long as they don’t forget to look.

The recreational diving industry is mostly self-regulated, but this has to date worked quite well where the actual underwater parts are concerned. Equipment from a reputable manufacturer will pretty much always work, and instructors or dive masters certified by a reputable agency will generally know what they’re doing. But if you’re taking a boat to the dive site, the boating part is generally regulated by the local coast guard, and depending on what coast you are diving that can be hit-or-miss. If it looks sketchy, maybe skip that trip.

Next, let’s look at the gear you’ll need to do this safely and effectively.

The most important, at least in temperate climates, is a wetsuit. Off the California coast, water temperatures are typically around 15°C, and while you can survive as long as two hours at those temperatures, really you’re going to be back on the dive boat wrapped in towels and swearing off diving forever long before you’re worrying about things like air supply and decompression sickness. In tropical waters, you could go without a wetsuit, but see above regarding sharp, jagged, venomous things. You may from time to time see bikini-clad models posing for underwater shots in e.g. advertisements for dive gear, but on an actual dive pretty much everyone will be wearing some sort of full-body protection.

Traditionally, this is closed-cell neoprene foam rubber, anywhere from one to seven millimeters thick, maybe thicker over the torso. Almost certainly a separate hood and boots, possibly gloves. You’ll sometimes see these described as working by “trapping a layer of warm water against the body”, but really they work by being a closed-cell foam insulator. It’s just more trouble than it’s worth to make them watertight, so you happen to get wet when you’re wearing them. Getting the fit right is vital, and if you’ve got any sort of non-standard body shape, strongly consider having one custom-made. Also consider more modern materials than plain neoprene, offering better flexibility and comfort.

Next, you’re going to need a mask, because there’s not much point in going down to see all the neat stuff if you can’t see anything. Even the best dive masks distort underwater vision to some extent, because of the refractive index mismatch, but it’s far better than trying to see anything under water without a mask. Dive masks are not interchangeable with swimmers’ masks because they have to be able to handle significant pressure differences and because they have to enclose the nose. Having the nose inside the mask lets you equalize pressure inside the mask; if you find yourself at 40m with your mask still filled with sea-level air, that’s going to be exceedingly uncomfortable even if the mask survives. Also, water will leak into your mask, and a forceful exhalation through the nose will clear it out through the seal or port at the bottom.

After that, a weight belt or integrated weight system. Human bodies are buoyant even before you encase them in closed-cell foam and put a big hollow air tank on their back. I don’t care how fancy the rest of your gear is, without a weight belt everybody just laughs at you kicking furiously on the surface and occasionally managing to get down ten feet or so. At the simplest, this is a simple nylon belt with a quick-release clasp, threaded into a bunch of standard lead or iron weights of 2-6 lbs. Anywhere from 10-40 lbs of weight may be required, depending on your build and gear.

Speaking of kicking furiously, you’d better be using swim fins of some sort. The human body isn’t made to maneuver under water, and most of the swimming strokes you learned growing up really only work on the surface. And without dragging a bunch of cumbersome gear through the water with you. If you want to do more than just sink to the bottom and sit there, you’re going to need flippers like a critter that was born for the water.

Five paragraphs, and I still haven’t mentioned breathing apparatus. With all the stuff I mentioned above, you can at least go snorkeling (well, OK, add a snorkel), which gives you a pretty good look at nifty stuff down to 5-10 meters. With the shiniest breathing apparatus and none of the stuff I mentioned above, it’s a waste of time to even get in the water.

Most recreational and even professional diving gear is open-cycle: you start with a tank of air or something like it, inhale each lungful once, and exhale it into the ocean. When the tank is empty, you’re done. Well, really, you’d better be done when the tank is down to about 500 psi (30 bar). But you’re starting with a tank, and the industry standard is the “Aluminum 80”. Eighty cubic feet of sea-level air, compressed down to 0.4 cubic feet of actual volume at 3000 psig (200 bar), contained by about thirty pounds of aluminum. Sometimes steel instead of aluminum; never fancy ultralight materials because every pound of weight you “save” on the tank is one more pound you have to add to your weight belt.

A standard 80-cubic foot tank will last about two hours (with safe reserves) for an average diver at the surface or in very shallow water. Air consumption scales roughly linearly with ambient pressure, because the need to clear CO2 from the lungs requires a constant volume of air no matter how dense or oxygen-rich it is. So at 10 meters, that tank will last only one hour, forty minutes at 20m, and twenty-four minutes at 40m. With substantial variation between divers. Tanks of 40 to 120 cubic feet are commonly available, and you’ll occasionally see double-tank rigs.

But you can’t breathe compressed air straight from the tank. So you’ll need a couple of pressure regulators. The first attaches directly to the tank, and supplies air at (usually) 150 psia (10 bar). That’s enough to push air through a narrow hose fast enough to keep up with demand, but not so high that the hose becomes excessively rigid. The primary regulator actually feeds a manifold with four hoses, which we call an “octopus” because there’s no such creature as a quadrapus. One of those hoses (I’ll talk about the other three later) goes to the secondary regulator in your mouthpiece. The secondary regulator is controlled by a diaphragm referenced to the ambient environment, with a slight and adjustable offset so that it delivers gas at a pressure slightly below ambient. In equilibrium, the regulator is closed and no gas flows. As soon as you start to inhale, the pressure in your mouth drops, and the regulator delivers gas at whatever rate is needed to maintain that pressure. When you stop inhaling the regulator closes, and when you exhale a set of check valves open to release the exhaled air into the water. If the regulator is properly set, you can breathe pretty much normally so long as you keep the mouthpiece between your teeth and don’t try to breathe through your nose. It gets difficult when you’re almost out of air and the first stage can’t deliver the full 150 psia, but that’s your indication that it’s well past time to go up.

Because this is a simple open-cycle system, everything you exhale goes straight into the ocean as a stream of bubbles. That’s wasteful, because you’ve probably used only a quarter of the oxygen in each lungful of air. And the bubbles can be a problem. They give away your location if you’re trying to be sneaky, they can disturb marine life, and if you’re in a cave or shipwreck they can accumulate in trapped spaces above you. On the other hand, they can also be a plus. They help you see where your fellow divers are, and they help the crew of your dive boat keep track of you all. They also are a strong signal to sharks that This Weird Thing Is Not Food. They’ll figure that out in one bite anyway, because sharks hate the taste of neoprene, but better they figure it out in zero bites. Marine mammals, on the other hand, see the bubbles as an indication that you are One Of Us, and may be up for some playful fun.

The second hose of the regulator goes to a handheld unit that includes a mechanical pressure gauge to tell you how much air you have left, a magnetic compass for navigation, and a depth gauge and/or dive computer. If all you’ve got is a depth gauge, you’ll also need a pressure-resistant diving watch and a laminated card with a simple set of tables for quick and conservative calculation of safe time at depth. Most divers now use electronic computers that perform a more sophisticated calculation and have a backlit LCD screen to display depth, safe dive time remaining at the current depth, and other useful information.

Third hose goes to the Buoyancy Control Device (BCD). This is basically the harness to which your other gear, especially the tank, is attached. The name comes from the fact that it includes inflatable bladders for adjusting buoyancy. These can be inflated by compressed air from your tanks or manually through a separate mouthpiece, and deflated through vent ports. We’ll talk more about buoyancy control in a bit, but the bottom line is that you don’t want to depend too much on your BCD for that. And it isn’t strictly necessary at all; in olden times divers didn’t have BCDs, and even now some divers just use a plain backplate harness to hold the tank. But a good BCD makes it easier.

Next, redundancy and safety. Your regulator might fail, so the last hose on the octopus goes to a spare. Not just for yourself, but to share air with your buddy who somehow ran out. You’ll sometimes see divers use a second, smaller air tank of 10 cubic feet or so for still more redundancy, but that’s uncommon in recreational diving. A snorkel is also useful for swimming at or near the surface without drawing on your stored air. If you’re diving anyplace you might get tangled, a knife is recommended. Anyplace dark – and deep water is dark-ish even at noon because water isn’t really transparent – you should have a waterproof dive light. Or two. Maybe an inflatable marker buoy you can deploy to tell your dive boat where you are.

All of this will be as simple as it can reasonably be; nobody wants to bet their life on e.g. fancy sophisticated electronics working in this environment. Even the pros we’ll be talking about next time, keep it simple.

And finally, the most important piece of safety equipment, a redundant diver. Seriously, don’t dive without a buddy unless you are very experienced and diving in very benign circumstances. You’ll also want a dive master who is familiar with the local waters, and if you’re diving from a boat you want a couple of people on the boat – one to make sure the boat doesn’t go away, and another to jump in and rescue you if you come to the surface too exhausted to reach the boat.

Obvious question: How much does all this cost? A good dive buddy is priceless, but the rest of it you can get for money. A full but basic set of dive gear will cost about $1500. Alternately, you can rent it for $50 a day or so. But there’s a core set of gear (mask, fins, gloves, etc) that tends to be very personalized and almost everyone buys for themselves early on, figure $200 for that unless you need a custom wet suit, in which case $500. The price goes up in a hurry as you get into more advanced capabilities, of course. Figure $400 or so for initial training.

Necessary skills, assuming you already know how to swim, start with the aforementioned Stupid Diver Tricks and how to avoid them instinctively. Then you need to learn how to set up, take down, and maintain your gear. How to plan a dive, including your estimated air and decompression limits even if you are going to use a computer. How to safely enter and exit the water, from a beach or a boat, while wearing flippers and up to a hundred pounds of clumsy gear. General familiarity with the underwater environment, which is freaky weird and unnatural until you get used to it. Assorted emergency procedures – “ditch your gear and float to the surface, blowing bubbles all the way to make sure you don’t accidentally hold your breath” will almost always work within the limits of basic recreational diving, but you really want a suite of less drastic options like “ask your buddy to share his spare regulator”. Which, incidentally, means learning a basic set of hand signals. A bit of underwater navigation, but you won’t be going very far at first. Some miscellaneous health and safety stuff.

And then there’s buoyancy control, which is a big deal and usually the skill by which divers judge one another. If you’re just a little bit too buoyant, you can waste a lot of energy kicking to maintain depth (and you can ascend dangerously fast). If you’re not quite buoyant enough, you can wind up hitting the bottom. That can mean kicking up enough mud and silt to wreck the visibility for everyone, or disturbing sensitive marine life, or tearing through wetsuit, skin, and flesh on sharp coral. Unless there is no bottom, in which case hey – why am I at 60 meters and my computer is telling me I need a ten-minute decompression stop but I’ve only got five minutes of air? The first step is getting your weight right, which you should have a good estimate for and you should check as soon as you get in the water. Then there’s your BCD, but you really shouldn’t depend on that. The air bladders are elastic, which means the amount of buoyancy you get depends on depth. And it’s unstable – go up five feet, and the air in the bladders expands, so you’re more buoyant and you tend to go up even faster. And vice versa. But most people use them at least a little bit. Really, what you want to use is breath control. Since you can’t hold your breath, you should be taking lots of shallow breaths. But that can mean cycling between 100% lung capacity and 75%, or 0% and 25%. Which gives you three-quarters of your lung capacity to use as dynamically adjustable ballast. Need more buoyancy? Take a deeper breath, and then exhale only a quarter of it.

You can learn enough for a basic open-water certification couple of weekends and some home study, but your buoyancy control will mark you as a noob until you get some experience.

What can you do with this? At this level, you can go down to 20 meters (65’) in calm open water in broad daylight and look at all the neat stuff for maybe an hour at a time. Fortunately, most of the neat stuff in the ocean is no deeper than that, because that’s where enough light reaches for plants to grow. You can play around in a freaky unnatural weightless environment. You can pick up things that are in reasonably plain view on the bottom, be that pretty seashells, tasty lobsters, or pirate treasure. Check your local laws on those. And you can do some basic utilitarian things like simple underwater inspection and maintenance on your boat.

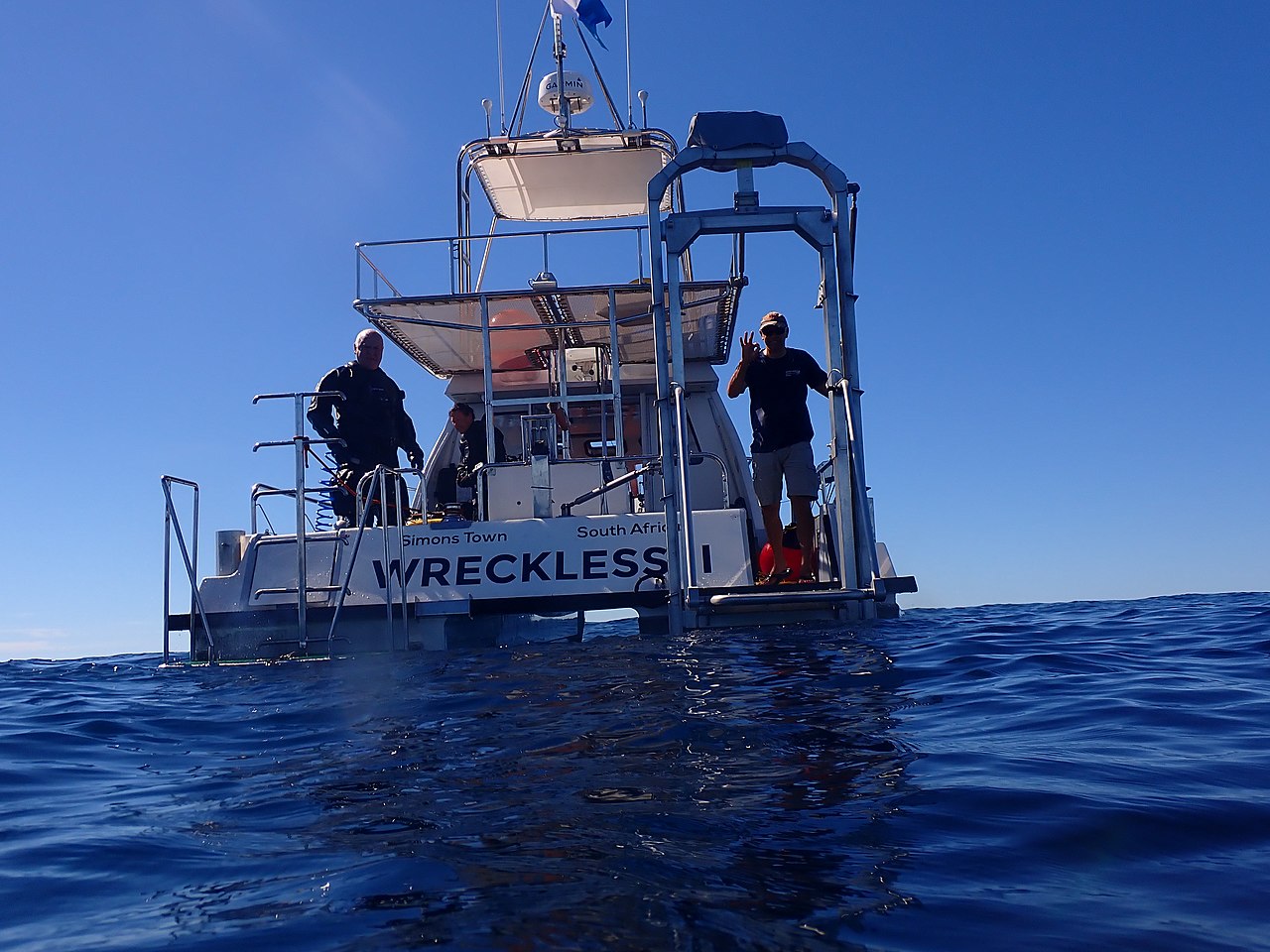

But note that most of the ocean is not full of neat stuff. Mostly, it’s either rock, or sand, or mud, and a very occasional school of fish because that’s all the local biosphere will support. And with the very best underwater visibility being 100 meters or so, and often only a tenth of that, you’re not going to see neat stuff unless you dive pretty much on top of it. Basically, a clear day under water is like an incredibly foggy day on land – which adds to the freaky unnatural ambiance and can be fun in its own way, but makes randomly exploring the ocean a losing proposition. You’ll want a map or a guide. Some of the neat stuff is within easy swimming distance of the beach, though note that wading through surf in dive gear can be tricky. There are places like the Catalina dive park where a kelp forest with lots of natural and artificial neat stuff is close offshore, with concrete steps running down to just below the low-tide line. But at some point you’re going to want a boat. Most common is a 40-80’ purpose-built dive boat with e.g. air compressor, swim platform, and racks for dive gear. These will take a couple of dozen divers to 2-3 local dive sites over the course of a day. Spartan accommodations, but often a bunk room so divers can sleep while the boat departs at zero-dark-thirty to arrive at the first dive site at dawn.

For more distant dive sites, you will of course need a bigger boat; these are the “liveaboard” dive boats which go out for a week or so in prime diving areas. Think in terms of a small yacht optimized for capacity rather than luxury, small double cabins, and of course the specialized dive support facilities. Eat, sleep, dive, repeat several times per day (and maybe a night dive). If you’ve brought the right companions and the boat has a good cook, this makes for a wonderful vacation.

With more advanced training, but still within the realm of recreational diving, there are more opportunities. Most obviously, depths of up to 40 meters (130’) are accessible. Most of the neat stuff is within 20 m, but not all of it and sometimes it is worth it to go deeper. You can also go farther afield, with a bit of navigational skill. But not very far – you probably won’t make more than a knot or so sustained swimming speed, and see above re how long your air will last. Two knots for short periods, but with proportionate increase in air consumption. Note that this also limits the currents you can deal with. Maybe a bit more than two knots if you stay in the boundary layer near the ocean floor, but not much more. Or you can drift-dive, letting the current carry you past an assortment of neat stuff (e.g. along a reef) while your boat hopefully drifts at the same rate above you. But in all cases, you’ll be limited by navigation. GPS doesn’t work under water, there are rarely useful landmarks, so you’re limited to dead reckoning with a magnetic compass in low visibility. If you can keep your position error to ten percent of your travel distance, you’re doing pretty good.

At this level, limited underwater exploration become feasible – you can dive into an area where you have only a reasonable suspicion that there will be neat stuff to see, and go looking for it. But even here, you’re talking about maybe a square kilometer’s worth of cursory exploration in a full day of diving.

Night diving lets you see all the nocturnal sea life, and even the inanimate objects take on an eerie appearance that’s worth the experience. But easy to get disoriented without training and experience.

Wreck penetration diving, and cave diving, are particularly dangerous without the right training and gear. This is where you get disoriented, entangled, cut, impaled, and/or trapped if you do it wrong. Also, an interesting shipwreck in less than 20 meters of water is often one that was worth refloating and repairing, so you’re frequently mixing this with deep diving. But it is within reach of trained amateurs. I’ve had the training, but my field experience has all been at the “easy” setting; ships deliberately scuttled after having their entrapment hazards cut away for the benefit of future divers. My regular dive buddy has visited the Imperial Japanese Navy in its natural habitat at the bottom of the Truk lagoon, but that’s a bit out of my league.

Limited search, recovery, and salvage diving is possible at the recreational level. Yes, that could include pirate treasure in the Spanish Main, if you somehow have privileged knowledge of the wreck site. More realistically, if e.g. your friend loses her engagement ring overboard on a boat trip, if you’ve brought dive gear there’s a fair chance you can get it back. But it won’t be easy, because see above re visibility and the sea floor will not be a neat, featureless plain.

I generally let other people do the photography and then just copy their best stuff off Facebook, but with the right training and equipment underwater photography (and videography) can produce spectacular results. The right equipment can range from a pocket camera in a waterproof housing, to ridiculously cumbersome and expensive camera-and-light rigs.

And finally, many recreational divers train in underwater naturalism so they can do more than look at the neat fish but e.g. participate in conservation efforts. Or at least understand the neat fish they are looking at.

So that’s about it for this round. Scuba diving is always cumbersome, but at the basic recreational level that means a couple weekends of training, a few hundred dollars for equipment, and a couple of hours of “this can’t possibly be worth the hassle” as you gear up and get to the dive site. That’s where you hopefully find out that, yeah, it’s worth it. But as you go deeper, stay longer, and do more than just look at things, the complexities increase enormously. And if you think of some clever way to make a fortune and/or win a war using this newfangled breathing-under-water trick, now maybe you have an appreciation for why four generations of very clever people haven’t made all that many fortunes or won all that many wars this way. More on that next time.

Comments

I took two things away from the dive course I took: a reflexive inability to hold my breath underwater, and the trivia that most dive incidents happen on shallow dives, because the pressure at 10m is double the pressure at sea level.

And an annoyingly funny story about the check dive. I underweighted myself, which meant I spent the entire underwater time having to "swim down" just a bit, which meant I ran my tank down just a little bit faster, which meant I (and my buddy) ended our dive just a little earlier than the rest of my class. Also, this was in a quarry in the Poconos in March, so the water is cold, probably a little too cold for the wetsuits we were wearing. The instructor showed up in a drysuit, and then had the nerve to visibly complain in front of the class that he'd gotten a bit of leakage at the neck seal...

I too have visited the Imperial Japanese Navy in its natural habitat at the bottom of Rabaul Harbour (at depths of down to 51m) and absolutely it was worth it.

My sister was dive master on a dive boat where things didn't go so well. Things went so not-well that a hollywood movie was made based on the events, which is never a good sign.

Open Water is the movie.

@Doctorpat: Yeah, that was a Really Bad Day. Fortunately I didn't get around to diving in Australian waters until a decade or so later, and everybody was being very diligent about the post-dive headcounts. Hope your sister came through it OK.

@John Schilling,

99% of the time, she'd have ended up in some sort of terrible trouble, but for once in her life she saw that things were NOT GOOD(TM) and proceeded to actually do the sensible thing:

Front up to the boat owners and tell them that safety procedures were not sufficient and something needed to be done. They promised that a new safety system would be implemented next week.

Front up next week, point out that nothing was improved. Point out that SHE would be also responsible if bad things happened. They promise things will be fixed within a week.

2 weeks later, still nothing was fixed. She quit and got a job on a boat where she was far less stressed.

2 weeks after that, their luck ran out.

I have a personal question about this.

I've never done SCUBA diving before, but it looks very fun. I have a chance to try it soon, but it would probably require learning from a non-licenced teacher in Vietnam. He probably knows his stuff but... there's just no proof either way, and I'm guessing he will push us into diving as fast as possibe, with limited English.

Should I go for it? I have a high risk tolerance and really want to try SCUBA diving. But also I obviously don't want to die. I think I'm pretty good at staying calm and regulating my breathing (no problem with underwater swimming, etc). If I don't do this, it will be a long time before I get the chance to try again, if I ever do. I realize there's a chance this could go wrong but... I dunno. Less than 1%?

Non-licenced isn't ideal, but it's the limited English that I'd be most concerned about.

I recently tried snowboarding with a limited English instructor and it was fairly useless. Even native English speakers can struggle when it comes to teaching someone something new.

That's a tough call. It's certainly plausible that a capable SCUBA instructor in someplace like Vietnam might find it impractical to secure and maintain certification by PADI or one of the other big Western agencies, and I don't know of any Vietnamese equivalent. But only plausible, not even close to certain, and you do want someone competent with you on your first dive - the things that can kill you are unfortunately the things instinct and reflex will be telling you to do, and it's easy to panic and forget if you've never done this before.

As a veteran diver, I wouldn't be too concerned as long as I could inspect the equipment, but for a novice I'd really want a personal recommendation by someone I trust.

The language barrier probably won't be an issue with the actual dive, because you won't be speaking to each other anyway and the necessary communication is physical, not verbal. But if you're trying to learn the mechanics of diving from him on the spot, or just trying to establish confidence in his skills and professionalism, a language barrier can be a real problem.

Also, if you're going to be going beyond swimming distance from shore, you also need to assess the safety of the boat and its crew.

I think this is the wrong way to look at it - everything carries some risk, but you should try to minimize it to the extent possible, rather than needlessly going "risk on". Accepting the risk is one thing if you know what you're doing, particularly at the frontiers of what is possible, but adding risk well within the safety zone seems shortsighted. (On the other hand, a lot of places have trial dives, where you don't need a complete certification but are basically hand held by an instructor while you're underwater)

Moralizing aside, a lot of the dive places in the Far East do have PADI or NAUI licensed instructors with reasonable English proficiency, as well as a decent number of ex-pat dive instructors who are basically catering to "backpackers*" and the like. You may have to pay a bit more, but it's worthwhile. When I was over there (admittedly more than a decade ago...) both Vietnam and Thailand had good PADI certified dive masters.

The other option to look into is doing the "school and pool" part of certification at home, and then doing the open water dives in Vietnam or elsewhere - I know that's fairly popular for people who do the pool work in New York or Chicago in the winter and then go to the Caribbean for the actual fun part.

*Actually people on a gap year living in hostels, not really "backpacking" in the Yosemite/Appalachian Trail sense of the term.

Every time I read a little about diving, my conclusion is that "The human body isn’t made to... under water." I'll stick with going as deep as I can hold my breath for!

Having done both Actual SCUBA and snorkeling; snorkeling gets me something like 90% of the SCUBA experience, and I have had more fun since I don't worry about all the ways SCUBA can go sideways, I'm usually soloing (in supervised waters! not alone in the ocean) and therefore don't have to track my dive buddy, &c

Great summary. I was surprised to find out in training that you can hold your breath under a pressure difference big enough to damage your lungs. I would hate to have been the first person to find that out.

A few random points from my experience of around 60 recreational dives (none-recent):

In my experience British, German, Israeli and American instructors are suitably safety conscious. French and Italians, not so much. Obviously I am extrapolating from a limited dataset here. But I think there are cultural differences. Anyway, tried to avoid diving with anyone with a 'macho' attitude.

A not insignificant number of dive boats have sunk in the Red Sea in recent years. Audits of Egyptian boats have shown big failures of safety standards. Again a cultural difference I think. Anyway, try to check out the bona fides of the company that owns the boat.

Nitrogen narcosis is real. I turned into a kleptomaniac diving on a trawler wreck in the med. I had no idea that I was behaving oddly at the time. Trying to detach a manky old curtain and stick it in my BCD seemed quite logical!

I have been diving with people that shouldn't have been in the water. If you aren't a good swimmer and don't feel confident in the water - don't scuba dive. If the thought of taking your mask off underwater makes you panicky - don't scuba dive. You won't enjoy it, and you might put yourself and other people in danger. If in doubt, try some snorkelling first.

Scuba and snorkelling are both brilliant, but quite different experiences.