A great deal of ink has been spilled around nuclear strategy, and most of it has vastly overcomplicated the issue. The most basic principle is that nuclear weapons raise the cost of war to the point where it is completely obvious that there is no way that war could pay. Note that the importance of nuclear weapons here is more in perception than in reality, because while through most of human history, war was very profitable, by the start of the 20th century, the destructiveness of military force had reached the point where a war would cost more than you could gain unless you got very lucky. Both world wars showed this quite clearly,1 but millennia of cultural memory of war paying (because, among other things, the cultures that did war were the dominant ones) meant that this wasn't particularly clear.

Nuclear weapons short-circuited all of this. Their destructiveness is unquestioned, and if they are likely to be involved it's extremely hard to make the case that war will pay, even to yourself. This is the major reason we are currently experiencing the longest period of great-power peace in recorded history. So long as nuclear weapons remain in play, there's a very strong incentive for even the most reckless regime to not push things too far. This is deterrence, and Bret Deveraux has laid out a fair bit of the history here.

But there's still a gap between the theory of deterrence and putting it into practice. For starters, simple possession of a nuclear weapon isn't enough. You need to be able to deliver enough nuclear firepower that the other side gets the message that fighting a war with you would be a bad choice under their logic, even if they were to strike first in an attempt to take it out. Exactly what this means is going to vary widely depending on who you are deterring, best illustrated by a few examples.

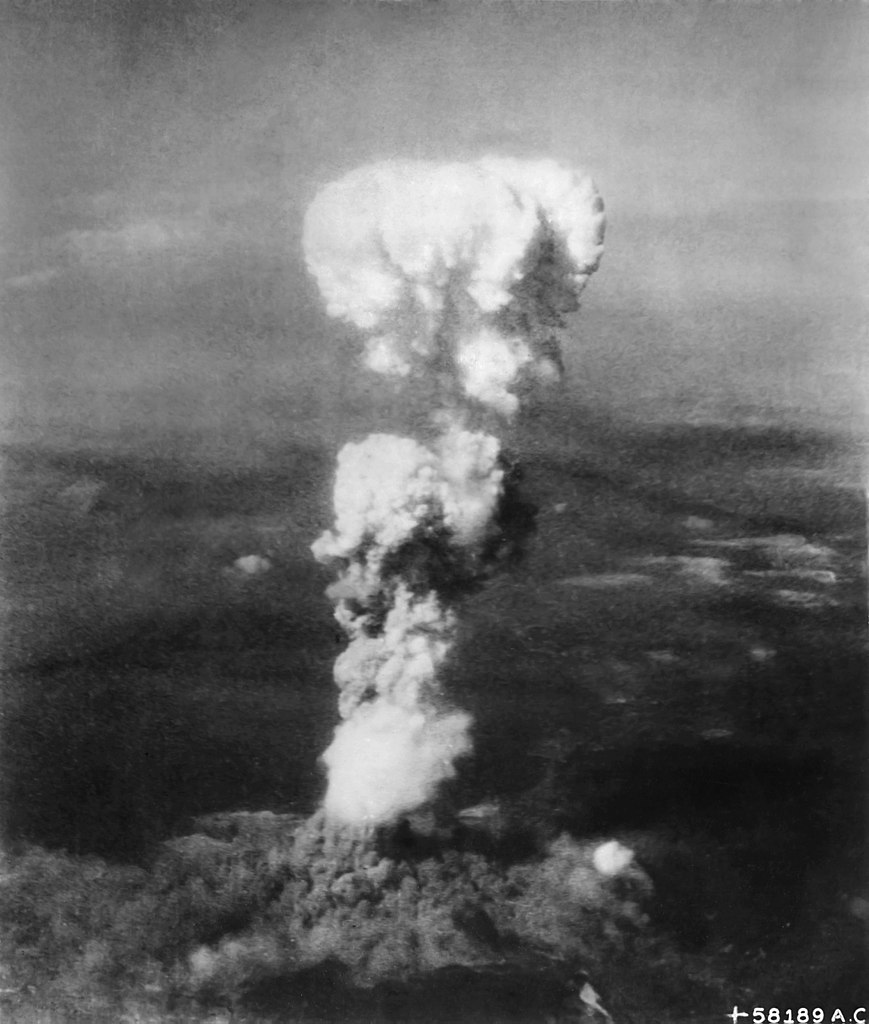

First, we'll take a look at the world's newest nuclear power, North Korea. They're a minor country directly facing down the world's leading military and economic power, which is historically a terrible place to be without a very strong patron, which they don't have. The alternative is nuclear deterrence. So long as the possible cost to the United States of doing something about North Korea is greater than the cost of not doing something, we'll leave them alone. And when the cost in question is a nuclear weapon over a major American city,2 then the US is going to be very reluctant to act. Nor does the downside have to be assured for the deterrence to work. The US Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system is primarily aimed at a North Korean attack, and intercept tests so far are successful about 50% of the time. But with only 44 interceptors and the possibility of a broader system failure, the President isn't likely to gamble on that keeping American cities safe unless he has to. The obvious move for the US is to try to take out the ICBMs before they launch, but North Korea has made this much more difficult by making its missiles road-mobile and hiding them in a large underground tunnel complex.

A North Korean nuclear missile

The end result of all of this is that the President is extremely unlikely to intervene in North Korea. Even if the probability of a warhead reaching an American city is in the single digits, that's still a massive downside risk, to say nothing of the far more certain risks brought on by a more conventional war. But note that in all of this, there is no way that North Korea comes out on top, and no real reciprocity in the level of destruction involved. The United States would survive without New York or Los Angeles. North Korea would survive primarily as a series of glowing craters.

But what about the opposite end of the spectrum? The US, at the height of the Cold War, built its nuclear arsenal around deterring a very different foe. First and foremost, Soviet leadership had to care far less about public opinion than did American leaders. When the American nuclear buildup began in the late 1940s, Stalin still ruled in Moscow, and he would have been perfectly capable of sacrificing a few cities to get what he wanted. So the American arsenal needed to be able to not only hurt the Soviet Union, but to cripple it economically and militarily. And while none of Stalin's successors were as ruthless, there was always the risk that a new Stalin would emerge. Beyond that, cutting the American arsenal would be seen, both internally and externally, as soft on Communism, so it declined slowly from its peak in the early 60s through the late 80s, when it then plunged thanks to the end of the Cold War.

The backbone of the American nuclear arsenal

But the details of the arsenal and how it would be employed varied wildly over the four decades between the invention of thermonuclear weapons3 and the end of the Cold War. Eisenhower, the first President to deal with this problem and an experienced General who knew virtually all of the key players on both sides of the Iron Curtain, was quick to recognize the basic logic of deterrence. He also saw that the Soviets would realize it as well, and that the most important thing he could do was to set up the United States for a long conflict, which meant keeping military spending as low as possible while still preventing the Soviets from expanding.

To accomplish this, he rolled out a "New Look", and a strategy where the US would respond to any attacks by the Soviets or their proxies with "massive retaliation" at a time and place of their choosing. This was against the background of the recently-concluded Korean War, which had been very costly, and where the use of nuclear weapons had been rejected. Eisenhower planned to prevent a repeat not through massive garrisons and conventional forces, but by promising that if the Soviets stepped too far over the line, we would attack them directly. The exact line was left ambiguous, giving the US the freedom to respond without actually destroying the world, and the policy worked to keep the Soviet bloc fairly quiet throughout the late 50s.

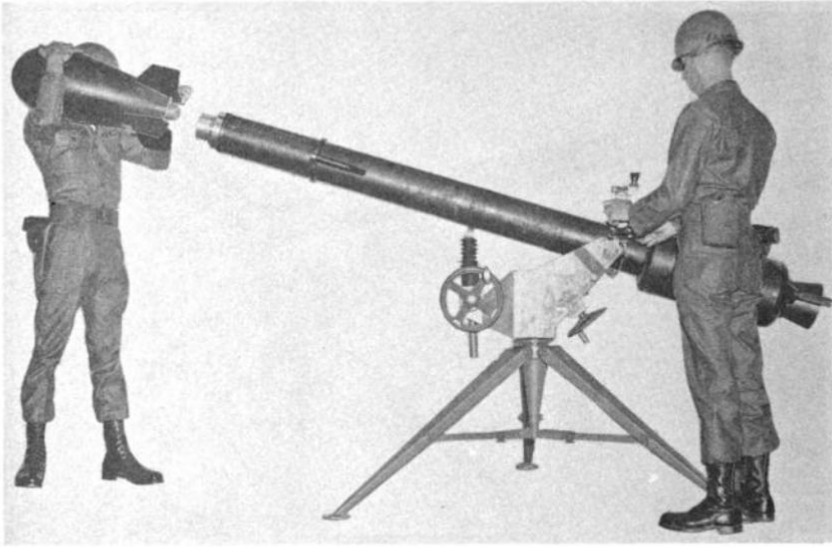

The Army under the New Look

The only real loser from the "New Look" was the US Army, which had seen deep cuts while funding flowed to the Navy and particularly the Air Force's Strategic Air Command, the primary organization tasked with carrying out the "massive retaliation". Even the forces that remained were restructured to optimize them for the atomic battlefield and equipped with large numbers of tactical nuclear weapons, intended to make it clear that attacking them would inevitably lead to nuclear war. Many within the Army were displeased with this, most notably General Maxwell Taylor. Taylor became a prominent critic of massive retaliation, which he believed would be unable to cope with Soviet incursions that didn't warrant an all-out nuclear war, and his ideas were welcomed by an up-and-coming politician by the name of John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy's defense policy was almost directly opposed to Eisenhower's. While Eisenhower had realized that the destructiveness of nuclear war would tend to cool heads, Kennedy and his administration believed that a nuclear exchange was almost inevitable without careful management from above. "Massive retaliation" was replaced with "flexible response", a strategy that cut nuclear forces and rebuilt the Army for limited conflicts in the Third World. To implement all of this, Kennedy relied on his Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, a man whose career had primarily been spent as a manager in the automotive industry and who thought he could run the DoD the same way. The results were immediate and disastrous.

Idiots at work

Kennedy, despite still having a massive advantage in strategic forces, repeatedly negotiated as if he had the weaker hand, and Khrushchev was quick to take advantage, attacking the West over the status of Berlin, which was becoming an increasing problem for East Germany as their population fled through the city. Kennedy more or less invited Khrushchev's preferred solution, built as the Berlin Wall, a major departure from his campaign rhetoric about "rolling back" communism. Khrushchev then tried another offensive, deploying ballistic missiles to Communist Cuba. Kennedy reacted far more violently than the situation warranted, bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war over a Soviet deployment that merely matched the US deployment of Jupiter missiles to Turkey before a solution was finally agreed. Both sides would withdraw their missiles, although in practice submarine-launched missiles quickly replaced them.

Kennedy's team then turned their eyes to the latest front, Vietnam, where for most of the next decade they would use the strategic theories developed to "manage" a nuclear war to manage a conventional war into a US defeat. So concerned were they with not escalating that they forgot to win, repeatedly restricting the target lists and backing off of anything that actually hurt the other side. It was only after American public opinion had firmly turned against the war that Richard Nixon, who had learned strategy from Eisenhower, took the handcuffs off American forces and twice forced North Vietnam to the negotiating table.

B-52s prepare to end the Vietnam War

But the debacle in Vietnam had given the Soviets the chance to gain the upper hand, both in their strategic arsenal and in conventional forces in Europe, the later exacerbated by serious morale and discipline issues in the US military during the late 70s. This was almost the problem that massive retaliation had been intended to solve, but there was little political will for it, thanks to wide acceptance of the logic of mutually assured destruction. Instead, it was hoped that tactical nuclear weapons could provide the edge NATO needed to stop the Soviet hordes, and that this could somehow be done without escalating into an all-out nuclear war. The Soviets, secure in their conventional superiority, adopted a so-called "no first use" policy in 1982, and pressured NATO to do the same. The Western nuclear powers wisely refused to take the bait, despite considerable Soviet propaganda efforts.

The late 80s saw the conventional balance in Europe swing in NATO's favor, thanks to the widespread adoption of new digital technologies that the Soviet Union's sclerotic economy simply couldn't match. Most notable among these were the new smart weapons, which gave the capability for a single airplane to take out a hardened target, a capability previously only available through the use of tactical nukes. Soviet attempts to rebuild their economy to respond to this, and to other economic attacks like Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, ultimately undermined the system and brought down the USSR.

"Tear down this wall!"

Many aspects of this have clear parallels to the situation we face in Ukraine today. NATO obviously has the upper hand in conventional forces, and is held back from intervening by the fear of nuclear retaliation, a problem the Biden administration has so far dealt with clearly in the mold of Kennedy, more focused on their fear of what the other side will do than on making them afraid of what we will do. This is best shown by their repeated statements of what they won't do, providing clear space for Putin to maneuver in, and things like cancelling previously-scheduled military exercises for fear that they would be seen as "escalatory". A better policy would be ambiguous but also assertive, making Putin wonder how far he can push us. For instance, a statement like "We stand ready to respond to any use of weapons of mass destruction against our friends with nuclear weapons" is both ambiguous and assertive. There's no clear commitment to nuclear war if Putin gasses Mariopol, but it also doesn't rule out responding to a nuclear attack on Ukraine the way that restricting the guarantee to our formal allies would. China would undoubtedly take notice of our assertiveness and be far less likely to take action against Taiwan, which has been the beneficiary of this kind of strategic ambiguity for decades. The ultimate destructiveness of nuclear war means that Putin should be as scared of us as we are of him, but that can only happen if we are willing to act more like Eisenhower and less like Kennedy.

1 The last great power war where the victor might have considered the war to have been a good idea in retrospect was the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), although even there Japan essentially bankrupted itself and had to settle for a lot less than what it wanted. The Sino-Japanese War is on firmer ground for this prize. The only potential exception involves seizing natural resources from a much weaker country, e.g. Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, but the world has decided not to tolerate that either. ⇑

2 North Korea accidentally-on-purpose showed a "nuclear targeting map" on a TV broadcast, with targets identified as Washington DC, San Diego, Honolulu, New York, San Francisco and Shreveport, LA. All but New York and San Francisco are the places where the people who would be planning a war against North Korea live, and perhaps more importantly where their families live. Shreveport is home to Barksdale AFB, home of Global Strike Command. And yes, North Korea has exactly six mobile ICBM launchers, and is unlikely to get more now that China has cut them off. ⇑

3 The hydrogen bomb was in many ways as revolutionary as the pure-fission atomic bomb, although the two were so close together that they tend to blend together in retrospect. As the reign of the atomic bomb was so short, I will ignore that era for the sake of compactness. ⇑

Comments

Don't most of these conclusions also apply to regular strategic bombing, which never really lived up to its hype?

Not necessarily within the scope of the article, but related:

In one interview which he did decades later, McNamara said that upon taking office as SecDef in 1961 he was horrified to learn that the US had a major strategic advantage over the USSR. And so, he was proud to say, he deliberately set out to eliminate said American advantage in order to (in his mind) reduce the likelihood of nuclear war - because he believed that a world in which the West was at constant risk of nuclear annihilation by the Soviets was a safer world than one where it was not.

@ike

The consensus around strategic bombing's effectiveness wasn't that strong to start with. Nukes are much more obviously destructive, particularly modern thermonuclear versions.

@Philistine

There's the reason I titled the picture of him "idiots at work". I have the semi-authorized biography of him, and need to sit down and go through it at some point.

I suppose most of this is because messaging to your opponents is as important as the actual strategy, but why not take the win of "agreeing" to a no first use policy while actually leaving that in the playbook? It's not like the warheads would somehow not launch if they changed their mind.

I suspect some of this is also that Eisenhower had (for most of his time in office) functional superiority over the Soviets in a way that allowed him to mostly dictate terms. As he left office, he had 10x the number of warheads as the USSR, and more credible ways to deliver them, and earlier in his term the disparity was even more marked. see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nucleararmsrace#/media/File:USandUSSRnuclearstockpiles.svg

That isn't really the case today, and I don't think the US really benefits from bluffing about it, because the Russians can count as well as we can, whatever their other failings.

Moreover, even if the US had 10x the number of weapons, we're "handicapped" by our very visible history of being extremely loss averse to both military and especially civilian losses since 1990 or so. The same logic that North Korea uses applies even more forcefully to Russia - even if they "lose" a nuclear war with the US, the US is so loss averse that they're not willing to risk it.

That's certainly not something we can rule out, but Russian nuclear doctrine isn't clear enough for me to be willing to state a position on how this impacted their doctrine in the field.

As for the nuclear stockpile under Eisenhower, yes, we had a big edge, although I don't think it was obvious how big an edge through most of his administration thanks to uncertainties about the Soviet nuclear force. A lot of it is just who is willing to be a bit more assertive. I'm not saying we should actively court a war with Russia. Just that we shouldn't appear paralyzed by the prospect, like we seem to be now.

I fail to see a meaningful difference between the nuclear strategy of today and a nuclear strategy that is like today but also makes Putin think twice about using chemical weapons in Mariupol.

The gain or loss is minuscle and there is no way of credible signaling that you will retaliate with nuclear weapons in such cases.

Taiwan ambiguity can do work because China has good reason to believe that Taiwan isn´t minuscle in the eyes of America, not because assertive ambiguity is a general solution for getting what you want.

Communication must lie reasonably close to the truth (as percieved by the national leaders) about national interest and behaviour, otherwise it will mostly be ignored and that carries a hefty price tag of possible misunderstandings about true red lines.

The point of a more assertive nuclear strategy isn't to make Putin think twice about CW use in Mariupol. That would be tragic, but there's not much we can do about it, nor do I propose there is. The point is to make him think twice about actually breaking out his own nukes, which would be a much bigger violation of traditional norms, and vastly more likely to lead to escalation.

As I understand it having the opposition think you're less likely to use nukes than you actually are is pretty much always a bad thing. If they think you'd be willing when really you wouldn't, they back down and you gain the benefits of a successful bluff. If they think you wouldn't be willing when you actually would, the nukes start flying and everyone loses.

Not always.

Scenario #1: something random happens. The opposition talk with you, you all figure out it was just an accident, and everyone stays peaceful.

Scenario #2: something random happens. The opposition think you're likely to respond by nuking them, so they decide to nuke you first.

I'm having trouble understanding how a country, any country, can change the perceived willingness it has to use nukes by, essentially, talking. There doesn't seem to be anything to talk about. It's the ultimate weapon, used when great powers are dead serious and/or afraid for their survival. Or against non-nuclear powers, but countries able to have nukes probably outmatch lesser powers conventionally too, so they don't even need them.

So nukes = great power total war, the kind that hasn't happened since '45. Either it hits the fan, and nukes get used, or it doesn't, and they don't.

It follows that the US won't go to nuclear war with Russia over Ukraine, and likely not over the Baltics either (or Berlin, for that matter). This has been the case since the Soviets had enough nukes to actually threaten the US, which is why conventional forces became fashionable again in the later part of the Cold War.

And if Russia nukes Ukraine (unlikely, but suppose) the US still won't get into that fight. Because it's still not an existential crisis for the US, so they won't risk New York to avenge Kiev. It's just the way it is, how can statements change the basics? What am I not getting? What should I read? Thanks

I think the question (that public messaging / "talking") addresses is exactly where they see the line of "dead serious / afraid for survival", versus something that they just address in a more normal manner. At the extremes it doesn't really matter, because nobody is going to use a nuke for a one off terror attack, and everybody will use a nuke if tanks are rolling into their capital, but there is a decent amount of gray space in between where the answer is "maybe". Like, would Pearl Harbor 2 justify nukes? Attacks on the US Minor Outlying Islands?

The other part of it is that back when battlefield / tactical nukes were more of a thing, there was more gradation in response and use cases, and thus more gray, whereas ICBMs/SLBMs are basically all or nothing. e.g. using nuclear SAMs/AAMs over your own territory, or nuclear artillery isn't necessarily supposed to be escalatory

That certainly makes sense. But I find most public messaging attempts to claim nuclear/existential status for obviously non-existential problems. Supplying missiles to Ukraine won't topple Russia. Nor will Russia nuking Kiev or China invading Taiwan topple the US. Even if troops end up shooting at each other, nobody wants to have their capital leveled over it, especially if it's happening relatively far away.

As Bean puts it, "A great deal of ink has been spilled around nuclear strategy, and most of it has vastly overcomplicated the issue" indeed.

It's less "doing this is worth immediately pressing the button" and more "this is important enough for us to raise instead of folding", with the accompanying risk down the road of someone pressing the button. And yes, countries can absolutely draw those lines and change where people think they are by talking.

Ok, how? How does a country state credibly that a situation is worth waging total war, risking annihilation and almost assured massive destruction, when that situation is not in any way conducive to total war? Existential threats are an objective thing, not a psychological case study about what one individual claims he finds annoying or not.

Nuclear line-drawing is a game where both sides are probably bluffing, but the incentive is to not call a credible bluff because if it isn't a bluff, the downside can be extremely high. The more credible the "bluff" is, the less likely it is to be called. And if you're not willing to set those lines pretty far forward, you're vulnerable to salami tactics. Also, note ambiguity. It's not "we will immediately nuke you if you invade West Berlin". It's "at a time and place of our choosing". That time and place may be "never" if you decide. Or it may not.

It's a bit off-topic, but I realised after rewatching this episode how much backstory they implied for that character with a handful of facts: Austrian accent, received the DSO at Arnhem, name is "Rosenblum", ended up staying in Britain.

"Existential threats are an objective thing, not a psychological case study about what one individual claims he finds annoying or not."

Except that "existential threats" can and do mean different things to different people, which is the literal definition of "subjective." For example look at the claimed justifications for war given by Imperial Japan in 1941, or the rhetoric from Russia in support of their current invasion of Ukraine.

Philistine:

At this point it is existential for the current Tsar who is unlikely to survive losing the 'special military operation'.

@Anonymous:

Now, yes. Was that true before the invasion, though? Most observers outside Russia would probably say no. Even now, most outsiders just want Russia to roll back to status quo ante (maybe status quo circa 2014) and ideally help pay to rebuild Ukraine. Not the destruction of Russia as a nation. Not regime change in Russia. And yet right from the first days of the invasion there was some very disturbing messaging from Russian politicians and media figures along the lines of, "What's the point of a world without Russia?" That's some pretty apocalyptic talk for something the rest of the world sees as an optional war on Russia's part, and it started well before it became clear that the invasion was going very, very badly indeed for the Russians.

Similarly, WW2 became an existential threat to Imperial Japan - or at least to the people and organizations in power when they decided to go to war. But did such a threat exist prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor? Again, an outside observer would almost certainly say no - but the Japanese government seemed to think that Western diplomatic and economic pressure to roll back their bloodthirsty campaign in China posed an existential threat to the Japanese nation.

So to my earlier point - people can and do see "existential threats" in all kinds of places, whether anyone else sees them or not. It's not objective, not really, because we're dealing with people; and people as a rule are really, really bad at being objective when it comes to themselves and things they care strongly about.

Thanks for all the replies, at least now I'm better aware where we're diverging. Basically, I still think the metaphor of the "game where both sides are bluffing" (and may I say, as a games maker, I take exception to the use of the word game, this is not a game, it's dead serious) breaks because everyone also sees everyone else's cards.

But limited wars were fought conventionally all during the Cold War even when that resulted in great powers losing. Nobody reached for the nukes, and my point is that everyone else knew they wouldn't.

I disagree with these examples.

Russia's invasion in Ukraine isn't existential, and it's not treated as such by either Russia or the west. It is for the Ukraine, of course, but they don't have nukes.

As for Japan in '41, my view is that they, as well as and everyone else, were aware that their fuel supply was utterly vulnerable to a hostile power that disagreed with their long term goals. They could either submit to US hegemony or fight it out. We know what they picked and how it turned out, but I can't see what's subjective about that situation.

Anyway, I'm going to stop harping on this. Thanks again for a chance to spell my thoughts out.

AlexT:

Yet the mathematics of nuclear war is called game theory.

AlexT:

Because those were peripheral conflicts in the third world, the loss of which did not actually threaten to allow the winner world domination.

The conflicts that might have resulted in nukes being used were never started.

AlexT:

It's not for Russia, but it is for the Tsar who will probably die if Russia loses.

Indeed, we could consider:

and so forth. Just because it's a "game" doesn't mean it isn't---or can't become---deadly serious.

@anonymous

I'd say at most that the mathematical discipline "games theory" is indeed used to study real-life situations (via extreme simplification, but usefully for limited domains), including conflict (of many kinds), including nuclear war. Calling it the mathematics of nuclear war is as inaccurate as calling thermodynamics the physics of nuclear war.

Indeed, and my point is that the categories are distinct. Total war vs limited war, as Clausewitz called it, right?

@Evil4Zerggin

Yes, games exist which are turned serious. At that point, they stop being games, just like a rock stops being a rock when it becomes a missile warhead. Philosophically, I think gaminess (as commonly used) refers to the degree to which the participants can stop or undo an action at any time, as well as decide the totality of its consequences. Courtyard basketball - yes, mostly; NBA - not so much. The litmus test - tell someone involved that what he does is "just a game".

Sorry for this late comment, but I've only just found this piece. I'm struggling a bit to understand the logic here. Your views here are quite far outside the US defense mainstream, as I'm sure you're aware, which makes me skeptical on the one hand but also makes me wonder whether there are real insights here.

For one thing, you ascribe the mistakes of Kennedy (Berlin wall, CMC, and Vietnam mismanagement--although the idea that Vietnam was winnable and/or worth winning is also fairly non-mainstream) to flexible response as a nuclear posture. But I don't see how this follows.

The logic of flexible response doesn't say anything one way or another about when to back down vs take a tough stand, which is the mistake you ascribe to JFK. FR simply says that if you decide not to back down, and things get to the point of nuclear use, you will use your nuclear weapons in a tit-for-tat manner in a ladder of escalation, with intermediate pauses for negotiation or cease-fire, rather than all-at-once as Eisenhower planned.

Zooming out, compared with more mainstream deterrence theorists you come across as not at all concerned about the credibility of threats and the way credibility factors into the strength of deterrence. Take the present-day example. The simple reality in Ukraine is that the American people would not be at all interested in burning to death for the sake of Ukraine, whereas the Russian people (1) have much less political agency and (2) have been pretty effectively propagandized to believe that Ukraine is of existential importance to their nation's existence. Escalation to the brink of nuclear war would likely cause debilitating panic in the US and not in Russia.

This means that the closer to the brink we come, the more this is to Russia's advantage, and if norms of keeping nuclear weapons out of the war can be enforced with diplomacy, that is only to the advantage of the US. This is exactly parallel to the reasons with the USSR declared no-first-use and pressured the US to do so--and as you point out yourself, this was a smart move on the Soviets' part. Now (as of winter 2022) we see that the US has gotten China onboard into pressuring Russia--diplomatically, not with nuclear threats--into backing down from their threats of nuclear use. It seems to me you were probably wrong about the right strategy to pursue in Ukraine. But again, I'm not sure I'm understanding the framework you're bringing to these issues, since it's so different from how most of the thinkers I'm familiar with have approached the nuclear question.

I will admit that this isn't an academic work, and I wasn't always great at keeping related concepts straight. You're correct that Flexible Response wasn't exactly responsible for Kennedy's missteps in those areas, but I do think it came out of the same root as those did. He was trying to manage what he saw as an extremely volatile situation, while Eisenhower (and I) see the situation as generally pretty stable. Nobody really wants to blow up the world, and so long as we stake out a reasonable position, we can use that to our advantage to stop the other side from escalating.

This also plays into thoughts about credibility. Basically, if nuclear war is negative enough in people's calculations, then even a vaguely credible threat is enough to keep things from going in that direction. And threats of the sort "don't cross traditional bright-line norm" are inherently more credible than ones that would involve crossing said norms.

Dave Baker:

Or maybe it is your views that are outside the mainstream.

Dave Baker:

Not really, all they needed to do was to stay for decades until eventually South Vietnam got a decent government and a military willing to fight against North Vietnam. Staying for decades is however incompatible with the military slavery system the US had in place at that time.

As for whether it would have be worth winning, had it been won it would probably be viewed that way though admittedly North Vietnam was never as bad as North Korea.

Interesting, thanks for replying to a comment on such an old post.

It sounds as if your view is pretty close to what I thought. I suppose I would add one point in defense of the more orthodox view (not just Kennedy's view, by the way... it isn't as if Nixon returned to massive retaliation, if anything he was even more of a "limited nuclear war" guy).

Anyway, the further point I'd make is that one doesn't need to be confident that the system is unstable in order to worry about credibility and move away from massive retaliation. One just has to be uncertain about whether the system is stable. And it seems to me that a high degree of certainty either way is unwarranted. The system hasn't been stress tested that many times, and some events (Arkhipov, Petrov, Able Archer) speak at least a bit in favor of instability.

@Anonymous

No, my view is definitely the heterodox one on this subject.

Re Vietnam, the South was in reasonable shape by the time the US withdrew in 72/73. The problem was that to continue to fight, they were reliant on American supplies and air support. In 75, neither was available. If the political will to keep them coming was available (say, Watergate never happens) then I think that we might well have a divided Vietnam today.

@Dave

That's what the "Recent Comments" section in the sidebar is for. More broadly, necros are encouraged, because I try to write stuff that will be worth reading beyond the moment.

Reasonable point about uncertainty and stability. My response is basically that I think the Cold War had a lot of close calls, enough that it's reasonable to favor stability over us having gotten lucky all of those times. Petrov in particular is often misunderstood. His superiors weren't blind or stupid, and almost certainly would have made the same calculation he did and not launched.