The first USS Constellation was one of the original six frigates authorized in 1794 to deal with Algerian pirates. She was built in Baltimore and went on to serve as one of the nascent country's main warships during the trade conflicts of the early 19th century. Today, USS Constellation is a museum ship in Baltimore harbor, alongside submarine Torsk and Coast Guard cutter Rodger B. Taney.

Constellation in Baltimore

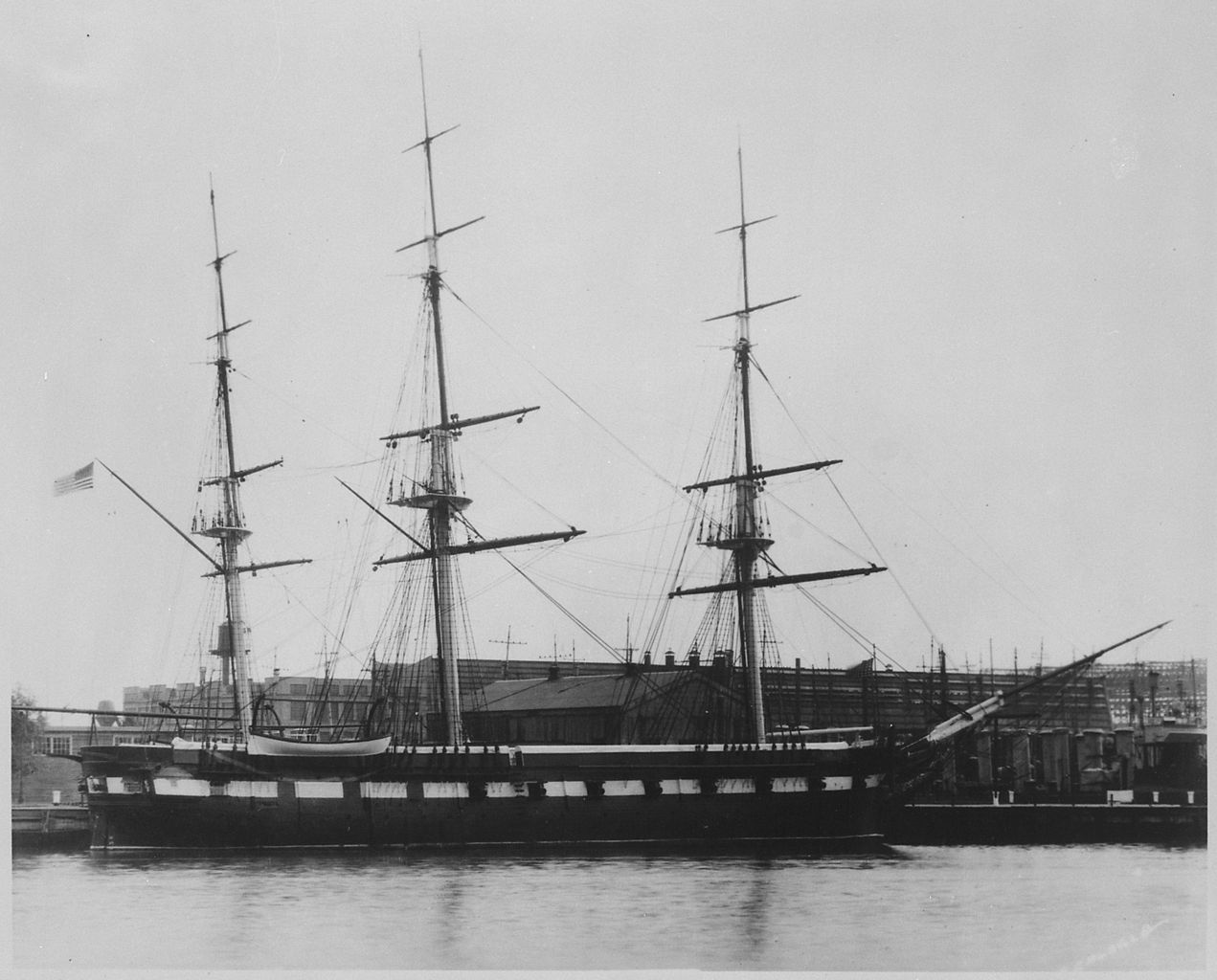

But the ship in Baltimore is obviously a very different ship from the one launched in 1797, the result of a major rebuild at Norfolk in 1853. After that, she served as part of the blockading force during the Civil War and spent two decades as a training ship, taking midshipmen around the world, before being hulked at Newport. She remained there for decades, serving as the official flagship of the Atlantic Fleet during WWII before the Navy finally decided to dispose of her in the fiscally strained years after WWII. The citizens of Baltimore began a campaign to bring her home that paid off in 1955, when she was donated and plans were made to restore her as far as possible to her 1797 configuration.

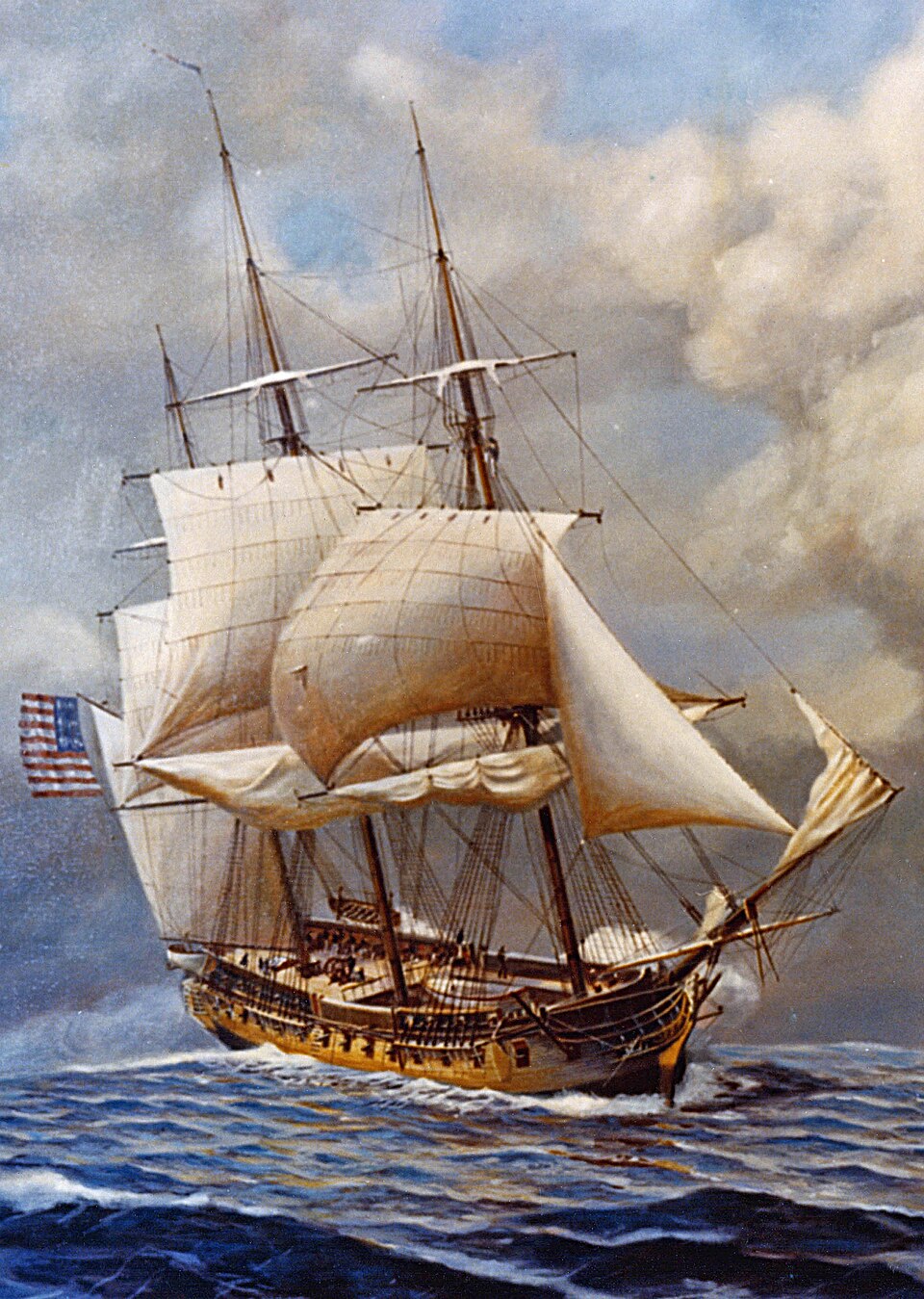

Controversy soon erupted over the actual identity of the ship, with some historians, most notably Howard Chapelle, claiming that the 1853 rebuild had in fact been nothing of the sort, and instead the Navy had spent money allocated for a repair on an entirely new ship, designed to the standards of 1853, to get around Congressional ignorance of the best way to maintain ships.1 But this was soon disproved thanks to the discovery of a number of documents in the archives, from letters dating back to the 1850s to several from FDR, who during his time as Assistant Secretary of the Navy for the Wilson Administration had written an article on the construction of the original six frigates. These definitively proved that the ship was still the original one, and while she had been almost entirely rebuilt from the waterline up, her underwater hull had been altered while under construction from the original design to the form visible in drydock, and the only change since then had been a 12' stretch amidships in 1853. This view was backed up by extensive research performed by both the Navy and the National Park Service. Even Chapelle knew the ship was original, but refused to admit it for some reason.

The original Constellation at sea

There's just one problem. Chapelle was right, and the ship currently in Baltimore was an entirely new design built in Norfolk in 1853, with only a tiny bit of timber transferred from the old ship to the new one.2 Under something called the "Gradual Increase Act", the Navy had stockpiled large amounts of timber, and was authorized under said act to use the timber as it saw fit, up to and including building new vessels and charging the labor to the Act.3 This power was rarely used because the Act didn't cover manning and maintaining new ships, but it does explain why the new Constellation was sail-only, even as steam was clearly the future. Boilers and machinery were not authorized under the Gradual Increase Act, so the new vessel would be the last American warship powered only by sail.

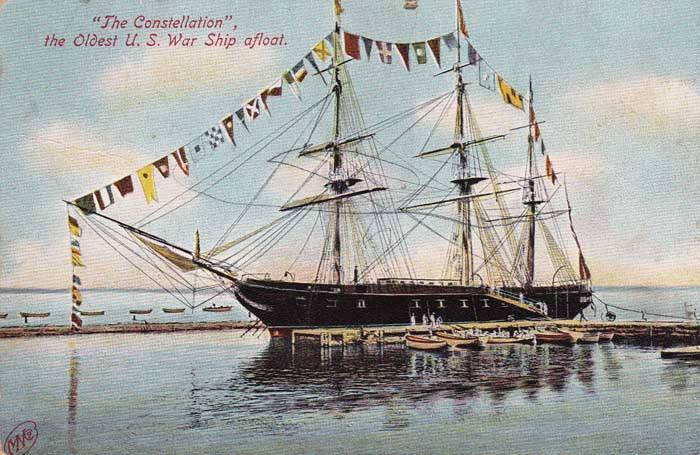

A 1910 Postcard of Constellation, right around the time people got confused

For the next 50 years, this was widely accepted, but in 1909 the Navy declared the existing Constellation to be the 1797 original for reasons that are still not clear. By the time plans were made to donate the ship, the issue had been fully obscured, and when the Navy went to investigate, they were unable to find records of the 1797 ship being broken up and thus confirmed that the ship was original. The 1853 "rebuild" was regularly invoked to explain all of the differences, which made the vessel 12' longer and 14" wider than the 1797 plans said. And it was important that the ship be original to those who worked to save Constellation, most notably a Baltimore railroad clerk by the name of Donald Stewart, who personally visited every Senator to lobby for the donation.

Chapelle, probably the leading expert on early American sailing ships, had started to question the ship's identity in the late 40s, and while the Navy's early responses were quite reasonable, by the time the donation question was being seriously debated in the early 50s, they had begun to greatly overstate the amount of work they had done. One researcher, when asking to look through the archives, was told that a comprehensive search had been done a year previously, although when he finally got his hands on the report from it, it was a mere 3 pages, and on the balance probably supported the 1853 date more than 1797. This report, and various statements by Navy officials over the past few years, were used to buttress the authenticity claims in the debate leading up to the passage of a law donating the ship in 1954.

Admiral Eller

After the ship was in Baltimore, things really went off the rails. The committee responsible for the ship began to view Chapelle as an out-and-out villain, who refused to admit that he was wrong for fear of embarrassment, and began a campaign against him. In this, they had two powerful allies. One was Admiral Ernest M. Eller, who had been appointed head of the Naval History Division in 1956 and joined the Committee shortly thereafter. The second was Donald Stewart, who in 1958 began to turn up an incredible collection of documentary evidence supporting the original origin. The first was a 1913 letter from FDR claiming to have evidence that the ship was not rebuilt, which Eller and the Committee trumpeted as proving their case.

But problems turned up with the ship was drydocked in 1960. The 1797 ship had been built with a 26" frame spacing, while the 1853 plans and the vessel in the drydock both had 32" frames. The ship's naval architect, Leon Polland, was confused by this, but soon concluded that the ship had been lengthened amidships, as was standard practice on the steel vessels he was familiar with.4 He believed he could see differences in the woodworking between the two sections, and his case was bolstered when a worker found a fastener stamped "1797" while restoring the ship. And the problem of the frame spacing was solved soon after thanks to another Roosevelt document found by Stewart. FDR had found a letter from David Stodder, who had supervised the ship's construction in Baltimore, discussing his modifications to the design, including the frame spacing. Other documents found by Stewart showed that the Navy was surprised by this in 1853, and tried to explain away a number of technical details during the "rebuild", which Chapelle claimed were only consistent with a new ship. All of this was revealed in a 1961 article titled "Yankee Race Horse", which the Committee hoped would put the question to bed.

Constellation in Newport, 1926

The extensively-footnoted article was enough to convince many bystanders, although Chapelle voiced his suspicion about some of the sources relied on, but the Committee was able to bring another authority into its corner two years later when the National Park Service designed the ship a National Historic Landmark dating from 1797. Of course, the NPS wasn't really competent to speak on the identity question, and had requested the Navy investigate the matter. Eller had simply replied with a letter restating the Navy's traditional position, and declaring that further investigation was pointless. Within a few years, the Committee was trumpeting that their version had been validated not only by several extensive Navy investigations, but also by a careful study by the NPS.

Dana Wegner's retirement in 2025, in the atrium of the David Taylor Model Basin

Chapelle and Polland continued arguing through the 1960s, although Polland was forced to back down from many of his stronger claims during the latter years of the decade. In 1970, Eller retired, followed by Chapelle the next year, while Polland was forced out of the Committee in 1975. Things were quiet until 1989, when Dana Wegner, curator of ship models at NSWC Carderock discovered the existence of a builder's model of the 1853 Constellation in the collection of the Naval Academy. This is something that would only have existed for an entirely new design, as a rebuild would have had most of the engineering work done in full scale because of the impossibility of accurately scaling measurements down and then back up. After verifying that the model was indeed a builder's model, Wegner embarked on a deep dive into the identity issue. The result was Fouled Anchors, a 200-page work that demonstrated quite conclusively the origins of the ship in Baltimore, and showed that the bulk of the documents relied on to make the 1797 case were clumsy forgeries provided by Donald Stewart.5 Very little of the material was found in archives where it would have been expected, and it seemed weirdly concerned with proving the 1797 origins of the ship, even if typos and very strange wording was overlooked. And it would later come out that the logs verifying the destruction of the original ship had been found, but were unavailable because Admiral Eller had them locked away in his classified safe.6 Occasionally, advocates of continuity with the frigate still pop up, but so far, none seem to have made much of a case.

Wegner's work was a deathblow to the attempt to portray the ship as a relic of the early Republic, and an entertaining read in its own right. It might have also saved Constellation. She had been neglected for years and was in serious danger of being too far gone to save, but the renewed attention, coupled with a new board that embraced her identity as the last survivor of the Civil War still afloat, managed to bring her back from the brink. I look forward to paying her a visit some day.

2 Specifically, about 186 cubic feet out of 19,000 in the entire ship. ⇑

3 Chapelle didn't fully understand this, and his belief that the "rebuild" was a way to put one over on Congress was the only major point he was wrong about. ⇑

4 Nobody seems to have pointed out that adding 12' by putting in extra 32" frames isn't physically possible. In fact, lengthening of wooden ships is typically done at the ends, not the midsection, but Polland was an amateur and didn't know this. ⇑

5 Stewart was not named as the forger in "Fouled Anchors", presumably due to fear of a libel suit, but Wegner later confirmed that he was indeed the forger. ⇑

6 Again, let me emphasize that the Director of Naval History was hiding documents to support the 1797 origin. I cannot describe how much this offends me as a historian, and wish he was alive so I could campaign for revocation of rank and veterans benefits. As he's long dead, I am instead considering lobbying for the naval history version of the Cadaver Synod. ⇑

Comments

...First, I have been hoping for years to see this subject pop up here - well done, and my sincere thanks!

When I wrote 'To Barbary's Far Shore', I ended up doing something of a dive into CONSTELLATION's history, which ended with a fortuitous opportunity to go aboard her in 2010. The best thing about that was admission let you stay as long as you'd like and go anywhere that wasn't specifically forbidden, plus the docents were absolutely amazing.

Needless to say, the Question popped up during my conversations, and their take was that the 1797 frigate - badly deteriorated and near derelict - was dismantled at Norfolk during the early 1850s, and some material (no one is sure what, how many, or where) ended up in the new frigate.

BUT....The docent said that in recent years, the Question had popped up again, and it was quietly simmering beneath the surface. I've not heard anything since, so I assume that it's been more-or-less settled.

Until the next time. ;)

And for what it's worth, I come down on the side of 1853 with at least some material from the 1797 ship in there. That material was almost completely removed and replaced during CONSTELLATION's rebuild and advanced preservation in the late 90s. She is absolutely worth the time, effort, and controversy spent on her - the last all-sail warship of the US Navy, defending free passage of the seas, stopping the slave trade, blockading an enemy, and serving as a flagship in two world wars.

That, gentlemen, is a record of pride and deserving of preservation.

Mike

I actually remembered you making a comment about that many years ago and went looking, but couldn’t find anything making the case for more than minimal continuity recently. There was a book in 2003 that Dana Wegner was not impressed by, and his response had some details on material transfer.

But I am glad you enjoyed it.

Cadaver Synods are so 9th century. In this enlightened era, we just edit the subject's Wikipedia page. For which purpose, this post and its references would I suspect be adequate evidence if someone were so inclined.

Making this prominent in his wiki article would be a good start. I also think NHHC should investigate and if it's true, should make a very prominent statement apologizing for this behavior.

I feel terrible for Chapelle having to fight alone against institutional dirty tactics like that, and dying before being vindicated.

And it certainly doesn't improve my opinion of our institutions that they're willing to go to these lengths over something so petty. If the culture of these people tolerates hiding and forging documents over this, how can they be trusted at all?

This might be one of the few incidents of naval historical matters that would make for a good Netflix show

BerndL:

See Iowa Turret Explosion.

@BerndL

It's the nature of the work I do that a lot of nuance gets cut. I try to be careful, but if that's your takeaway, then I may have gone slightly too far. Chapelle wasn't entirely alone, although he was by far the most prominent advocate on his side, and I didn't want to spend a bunch of words on the deep minutiae of the case. Read Fouled Anchors if you want all that.

As for institutions, I think the only real villains are Stewart and Eller, and so far as there was institutional failure, it was only at Naval History under Eller. I do think the failure there was serious, but less as a broad institutional matter and more as an offense against Clio. Every other institution was basically too busy to care much, and yes, that does leave them vulnerable to being hijacked by interested parties, but that's largely because this wasn't that important of a question to, say, the Park Service.

Is claiming to have added 14" of beam to a wooden ship not an even bigger red flag than claiming to have added 12' of length? It's not like a steel-hulled ship, where you can weld bulges to the sides - if you want to add beam to a wooden-hulled ship, it seems to me that you'd have to tear the whole thing down and start from scratch.

I'm not sure, but I don't think so. There was talk of a waterline-up rebuild, and that could easily change the outer mold line of the above-water portions by 14". You might be sliding the old nameplate onto a new ship, but it's not the same sort of mathematically insane that changing the frame spacing or adding 4.5 frames is.