Five and a half years ago, I covered the announcement that the Italian FREMM class frigates would be adapted into the USN's new frigate, which was named the Constellation class after one of the original frigates a few months later. The idea was that by buying an existing design, it would reduce the risk of major cost overruns and help get the USN out of the shipbuilding doldrums it had been in ever since it was saddled with the LCS.

Unfortunately, none of this seems to have worked out. The program is currently 36 months behind schedule and well over budget, and the originally-planned 85% commonality has dropped to 15%, while the Navy and the shipbuilder, Fincantieri Marinette Marine (FMM), have pushed ahead with construction well before the design is even completed. Things have gotten so bad that Secretary of the Navy John Phelan that four of the six ships currently on order are being cancelled, and that the Navy will look elsewhere for a small surface combatant.

Now, this all leads to the question of what went wrong and why. Obviously, the adaptation process proved much more difficult than expected, to the point that several people affiliated with the program claimed it would have been easier to design a new ship. I actually wondered if they were basically planning to do that when it was first announced, making a new design that looked like a FREMM a la the Super Hornet, but it appears that they took the task seriously. But there were obviously going to be adaptation issues, and the design going from 85% the same to 85% different over 3-4 years implies that there was some very fundamental problem with how the program was conceived when the contract was signed, and several media reports hint that the big issue was survivability standards, most likely the design's shock resistance.

At this point, the obvious thing to do is to blame USN gold-plating, and say that things would have been fine if we'd just stuck to the Italian standards. This is a more complicated issue than it seems. The USN institutionally tends to demand a higher level of survivability than many others, lessons learned in blood, but on the other hand, it's not entirely clear that the tradeoff is worth the 3-year delay. Most likely the people involved kept telling themselves it wouldn't be that long, and I'm sure the decision to stick with traditional standards was influenced by one of the main criticisms of the LCS being its poor survivability.

But leaving aside the object-level question of what they should have done and if the Italian version was good enough, there's still the fact that everyone involved, both at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) and FMM, completely misunderstood what bringing the ship up to USN standards would entail. I don't have the visibility into the early contract period to know for sure who bears more of the blame, but suspect based on what we've seen that the problem here was mostly at FMM. If there had been major requirements changes after contract award, that would have been pretty notable (and is frequently called out as a bad thing that causes increased expenses on other programs) but there's been effectively no discussion of such changes anywhere. If FMM was unduly optimistic about its ability to meet the contract in the first place, then we would see more or less what we have seen.

USS St Louis at FMM before launch

In theory, this kind of thing should have been discouraged by the way the contract is set up. Constellation was bid using what is known as a fixed-price incentive contract. As you might expect from the name and a basic knowledge of government procurement, it's not actually for a fixed price. Instead, there are two main prices in this kind of contract, the target price and the ceiling price. The target price is what the contractor wants to hit if things go well, with diminished profit in case of cost overruns up to the ceiling price, which is the maximum the government will pay for delivery of the ship. At the moment, we're well above the ceiling price, so in theory, FMM is having to eat a bunch of losses on this. In practice, it looks like there has been a reasonable amount of money added to the contract to deal with the effects of inflation and workforce issues, but nothing much for requirements changes, which normally are negotiated separately. I tried to get a sense of how Fincantieri was doing financially on all of this, but their annual reports were unhelpful. In any case, the normal practice if the contractor screws up this badly is to throw them under the bus quite publicly, as has happened with, for instance, Boeing and the KC-46 program. Instead, the Navy has taken the bulk of the blame here, which suggests that FMM has powerful political interests on its side.

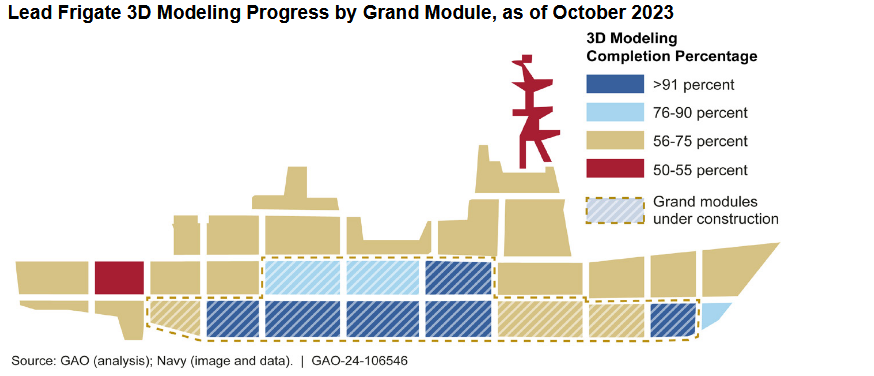

But there's other evidence that this program has been heavily beset by politics from the beginning. One decision that has attracted a lot of criticism was the choice to go ahead and start construction before the design was complete. Now, this sort of concurrency between design and build isn't necessarily a bad idea if you follow good engineering practices. There's no need to have the detailed design for the mast done when you lay the keel, and waiting around for it is just going to delay things. FFG(X) did not follow good engineering practices. Construction on FFG-62 began in August of 2022, and 14 months later, construction work was being done on modules that were still less than 75% design-complete. While bureaucracies often make stupid decisions, there are some decisions so bad that they can only be understood as the result of the bureaucracy optimizing for a different objective. In this case, that objective was undoubtedly keeping the program "on schedule" in the short term, presumably because someone didn't want them rocking the boat.

More evidence of this sort of political top cover comes from a recent GAO report, which describes the Navy as accepting incomplete or nonexistent design documents (p.18) and giving them 50% credit for completion, allowing the design to stay "on schedule" despite the fact that some of the documents were "without any design content from the frigate shipbuilder". I regularly work with similar document deliverables for the government, and if I proposed sending in something blank so that we met our deadlines, I'm not sure who would be more upset, my management or the government. Again, this is such bad practice that it can only come via serious political pressure to avoid rocking the boat. Eventually, things got so bad that the Navy's senior leadership had to acknowledge the reality of the problem, with a 12-month delay coming out in January 2024, followed by 3 more months in March and then a total of 36 months in April. At the time, it was blamed on workforce retention issues and supply chain hangups, but that's a pretty obvious lie when you're slipping a delivery from 2026 to 2029.

But what sort of political interests could drive this?1 Well, the first and most obvious answer is that Wisconsin is a swing state, so there was apparently political pressure even back in 2019/2020 to award the FFG(X) contract to FMM, and to avoid pulling this contract in ways that might cause serious job losses. Second, the yard is in a district that was represented by Mike Gallagher, who was a major player on the House Armed Services Committee until he resigned in 2024 to go into business. Third, there has been a lot of interest in bringing in foreign shipyards to fix America's broken shipbuilding base, particularly under SecNav Del Toro, who was in charge when the worst of this was happening. If we threw Fincantieri under the bus, no matter how deserved it was, other partners might be scared off.

But at least someone in Washington has finally woken up and cancelled the program, right? Unfortunately, the political forces that have shaped the program from the start continue to exercise their malign influence. Despite headlines about the program being cancelled, SecNav Phelan has chosen to keep building the first two units, effectively to preserve jobs at FMM, while saying that the Navy will examine other options for Small Surface Combatants. This makes absolutely no sense. Yes, the design phase of this program has been unusually bad even for defense projects, but it's mostly over, and we are going to have to complete it anyway if we are to build so much as one ship. And after we have built that one ship, we then can build others without having to do design again. Starting over means that we have to do design again, and even if everything goes absolutely as perfectly as it is possible to imagine, that's still several years of delay relative to just building follow-on Constellations. Also, we will be stuck with a two-ship force that requires a dedicated engineering support staff. As we've seen with the discourse around the F-35, many people are suggesting actions that might have made sense if executed a number of years ago, but will just drive up cost and delay the delivery of systems to the front lines today.

Bertholf, the lead National Security Cutter

Phelan has since announced that the replacement will be based on the HII National Security Cutter, which was probably the runner-up design in 2020. Besides the political aspects of the decision (FMM was running out of work with LCS going away, while Ingalls, which builds Burkes and most of the 'phibs, still had plenty) the major downside is that it is considerably smaller than the FREMM, thus limiting what systems we can put aboard. And while he's talking about getting something in the water by 2028, that seems like obvious nonsense. Ingalls generally has a reputation for competence, and they are unlikely to have messed up the way FMM did, but 3 years from order to launch is what you'd expect from a proven design in series construction, not the first of a class from a standing start. If they do actually try to make it happen, then the result will undoubtedly cost more and be later than if they'd just done it the right way. This mess will undoubtedly haunt the USN for decades, and is proof that we shouldn't appoint a Secretary of the Navy who doesn't even own a rowboat.2

Comments

They can always use plan B, also known as plan Burke, or they can go back to plan A, which is also known as plan Arleigh.

It’s not quite pharma, but the point about the first (pill/boat) costing an extra billion for the R&D still holds. If anything this is worse than canceling it on the ways.

Between this and the M-10 you sort of wonder if things are even worse than they seem in procurement land, though it seems like the B-21 (and F-47?) are counter points in general.

This is an apt example of the 3 legged stool: quality, features, the deadline. Pick any two. Picking the deadline early in a project is almost always a guaranteed loser.

Wait. No. Need more!

Given where the US was on around August 1st 2025, what would you have done?

If I was in Phelan's place, I would have made FMM bleed, and bought more Constellations.

How can he make FMM bleed? Push too hard and they just go under anyway. Besides, I'm pretty sure that even a 2029 delivery of the first hull is WILDLY optimistic.

The obvious thing to do is publicly drag them over the coals, and get really serious about that second yard. We'll keep them alive, but I'd really like it if the problems made it into their annual report with "this is why we didn't make as much money as we wanted last year".

In broader news, they've announced that their going for a minimum-change version of the NSC, which is not an adequate replacement for Constellation in any way. It will probably have RAM, and maybe a modularized VLS, but it will lack any serious anti-air or anti-surface capabilities. The ship that results is more like a slower, cheaper LCS than a proper frigate, and I suspect the attempts to get a hull in the water by 2028 will be aided by the recent cancellation of the USCGC Friedman, although it's unclear how much work was done before that happened. In any case, this is shockingly bad news if we expect our small surface combatant to do anything more than blow up small boats.

@Bean

I would be really interested if there is something about the tactic they want to use it for. Do high-end ASW with noisy CODAG ship with probably no noise cancelling is crazy. Flying ASW helicopter at bad weather from 4500 tons ship will be hard. Escort without AEGIS and good ASW is worthless. And using basically a Coast Guard cutter in front line combat is a complete suicide.

Is it really like "We just want frigates for number of Principal surface combatants to go up" on paper or there is some tactical reason they want to use them for?

@stupidbro

The rest is true but the USCG generally build ships able to operate helicopters in quite severe seastates due to their SAR missions. a National Security Cutter can operate helicopters in up to seastate 5 from what i've heard

@Pootis

I do not know how Pacific works but in North Atlantic Sea State 5 is not enough. Type-23 (which hull was designed specifically for stability) was capable of operating ASW helicopters only for 60% of time during winter months in North Atlantic and it was capale of launching at Sea state 5 and sometimes even Sea state 6. It was a tactical nightmare so FREMM and Type-26 were designed to be capable over 90%.

This whole thing makes less and less sense the more I look at it.

The only way they get a hull in the water by 2028 is to basically buy and off the shelf Legend class which is what it looks like they are planning. That means no ASW or AAW capability which means you can’t use the ship for convoy escort. If you’re just looking for something that can replace LCS in low threat environments that’s fine. But it’s not what the FFGX brief was when the program started.

They are talking about mission modules again like with the LCS. We all know how that ended. The only path that makes any sense is that you buy a limited number of Legends to get some hulls in the water and then once Constellation is in service you buy a bunch more as the bugs should be out by that time.

@StupidBro

You're assuming that the current Pentagon has thought that far ahead. Yeah, it's obviously a terrible replacement for Constellation. I think it may have a little bit better AAW capability than you give it credit for with the availability of ESSM Blk II, but the whole thing definitely doesn't sound great.

@Ski206

If they'd added this as a second supplier, that would make sense. They didn't.

Why would mission modules be less successful than StanFlex?

(Or is StanFlex less successful than I had previously understood?)

Like, if you have the money you'd rather have a completely equipped fully capable ship, but for smaller combatants (below the current DDG baseline), it seems like a decent compromise, at least on the weapons front. Sensors are obviously harder to fudge, particularly the ones that are generally built into the structure of the ship (radar and sonar domes, vs. towed arrays)

There's some indication from the Danish Red Sea deployment that StanFlex may not have done as well as we'd hoped. But more broadly, the issue is that even if we ignore the integration issues (which are solvable, but easy to overlook) then you still have pretty serious sensor limitations on the NSC design. I tried this in CMO, and against NSM, the ship got one shot off against a salvo that Constellation handled no problem.

@bean

Danish in all their future ships are now switching from StanFlex to the "Cube" system. Development of StanFlex is now officially dead.

Long time reader, first time comment.

As a replacement for the now cancelled Constellation Class, the USN plan to take the HII National Security Cutter, and use this as the basis for their new 'Frigate'.

As you have pointed out, the National Security Cutter is considerably smaller than the FREMM, which limits what systems we can put aboard, and hence, it value to the USN.

As the FREMM design is proven, is reliable, and, is in service with several navies around the World, why is the USN not, as an interim measure at the very least, looking to simply take that design (which they must put some stock in, given it was the chosen design for the foundation for the FFG(X)) and build that as their new frigate.

Wouldn't it be easier, and more expedient, for the USN to just take the FREMM design and build that, rather than modify National Security Cutter as the basis of a new Frigate?

Ps For the purposes of my question, given that the cancelled Constellation Class was an evolving design, that at the end shared approximately only 15 percent commonality with the FREMM, i consider them to be essentially two entirely different vessels.

I would love your thoughts on this.

@AC, the FREMM design has a non-US radar, non-US VLS cells, non-US EW gear, etc. I think about the only components that the USN currently could do logistics support for are the 76mm gun and the GE LM2500 gas turbine.

So the design was always going to have to be changed to some extent. It would kind of defeat the purpose of a low cost frigate if the things required a massive new parallel support structure to be built up as well.

Would it be possible to go back to the drawing board, start again with the basic FREMM and this time keep the changes to a minimum? Only way I could see this working would be to first exile everyone involved in the original Constellation design and procurement proces somewhere like Antarctica, and make sure they were kept there with no communications until the first Constellation take #2 was commissioned.

@Hugh Fisher

I argue that it would end up the same way. It is a design problem, not an engineering problem. I would guess there is not enough growth margin at the front of the FREMM to more than quadruple the weight of its radars and double the weight of VLS at the same time. The US Navy would need to adapt something like AN/SPY-7(V)3. I would be really interested in the reason why the USN is so resistant to adapting this radar to its lighter ships.

@AC If you think that Constellation development was problematic, you can not even imagine what it would be like trying to teach ESSM to communicate with EMPAR or Herakles radars.

@AC

I talk about this a bit more in the "No it's not" post, most of the way down. The size is a bit of an issue. A much bigger issue is that it's just nowhere near as capable as Constellation and we really should want the capability. But they can do what they appear to be planning to do plenty fast, certainly faster than they can build something like a straight FREMM. We already build NSCs, and it uses our systems, not a bunch of stuff we don't use and would have to either replace or support. Although at this point, we'd be able to build Constellation just as fast as FREMM.

@Hugh

My problem with this is that it assumes that the current team was wrong in some objective sense and/or incompetent, and I don't think that's a good assumption. We can have a debate over whether or not it was a good idea to impose USN shock requirements on the FREMM design. There's a good case for "yes" (those requirements didn't come out of nowhere, and we really would prefer our ships to be able to survive near-miss bombs and such) and there's a good case for "no" (a ship that isn't in the water isn't useful). The delays basically boil down to them picking "yes". You can disagree with that decision, but it doesn't strike me as obviously wrong or incompetent.

@StupidBro

Probably because we're standardizing on SPY-6 for just about everything. I'm also not sure it's as capable as SPY-6, but I can't fire up CMO to see what they think right now.

Thank You for all the responses.

Ps I don't know how I found this website about a year ago, but I am so glad that i did. The articles posted are fantastic, and the comments against them are so informative.

@bean I think there's even more of a case for exiling, or at least removing, the current team if they are competent! If the same people repeat the same process with the new Coast Guard cutter design, and nobody tells them they were wrong last time, the outcome will almost certainly be the same.

@bean

What I have heard. Italy is one of the European countries that uses the US standards, and if they somehow made a compromise with the French on something, changing it to the US standards should not be very hard.

If you are interested in Italian FREMM shock-resistance capabilities, this is probably the best source in English:

https://scresources.rina.org/resources/Documents/RINAMIL-2006.zip

The usual hypothesis, that I have heard, is that they needed to change the internal layout to balance the ship that became front-heavy because of the heavy US sensors and VLS. And this, together with meeting the US standards cause the disaster. I find it much more probable that everyone in the Navy, NAVSEA and Fincantieri just forgot about the US military standards when they chose FREMM.

And if you look at the currently constructed FREMM-EVO, where the Italians actually decided to put a very heavy flat panel AESA radars on the FREMM, they made a second mast on the back of the ship where they put half of the arrays. Here is how it looks:

https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2026/01/italian-fremm-evo-program-achieves-critical-design-review-milestone/

@Hugh

My entire point is that this disaster shows all the signs of being caused by political meddling, not engineering incompetence. Exiling those people would be shooting the messenger. Seriously, some of the stuff around submitting blank documents is wild if you've worked in that world. A coworker who I told about that was going "I think we'd go to jail if we tried that". I'm not sure he's right, but it's that level of insane.

@StupidBro

The CEO of FMM went on a podcast and, reading between the lines, basically admitted it was them screwing up survivability requirements. Note that the US book has multiple levels in it, and the FFG(X) required Level II (standard for destroyers and such) and it's possible FREMM is Level I (which LCS used, along with stuff like minesweepers).

@bean, I did write (somewhat hyperbolically) everyone involved in the original Constellation design and procurement. I'm not ignoring the political meddling.

Still, I don't think the design team can be completely absolved. A "designer" who never says NO isn't a designer, just a remotely operated mouse cursor.