Even though the Armistice on November 11th, 1918 had signaled the end of the fighting, the Great War had left many loose ends for the diplomats to tie up. One of the biggest was the fleet of battleships and battlecruisers the now-deposed Kaiser had built. 10 days after the Armistice, they had sailed into Rosyth, and they were swiftly transferred to the Grand Fleet's former base at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys to the north of Scotland, to be held there by the British until their fate was decided at the negotiating table in Versailles.

Hindenberg interned in Scapa

It was not a pleasant experience for either the officers or the men aboard those ships. Discipline in the High Seas Fleet had frayed during the long years in port after Jutland, and collapsed completely when the fleet was ordered to sail to its doom in late October. The British, when they came aboard the interned ships, were astonished at the lack of respect for the officers, whose orders had to be countersigned by the crew's councils, and at the amount of dirt which had been allowed to build up. The lack of food and recreation did not help. Food came twice a month from Germany, and while the rations were more generous than during the Turnip Winter, it was monotonous and of low quality. The only luxury available in abundance was brandy, which was necessary to make life less boring.

German sailors fishing from a destroyer

Scapa was not a popular posting even for British sailors. While black-market German brandy, acquired in exchange for basics like cigarettes and soap, could relieve some of the hardships of a dry base, the situation for the men aboard the German ships was even worse. They were not allowed ashore at all, even on one of the minor islands that dotted the area, and only officers on official business were even allowed to move between ships. The only available recreations were booze and fishing, which also supplemented the monotonous diet. Communication with the outside world was even worse, as the postal service was unreliable. While 20,000 men had brought the ships into captivity, their numbers fell rapidly, and a month after the Armistice, only 5,000 remained, a number that dropped slowly but steadily over the next six months.

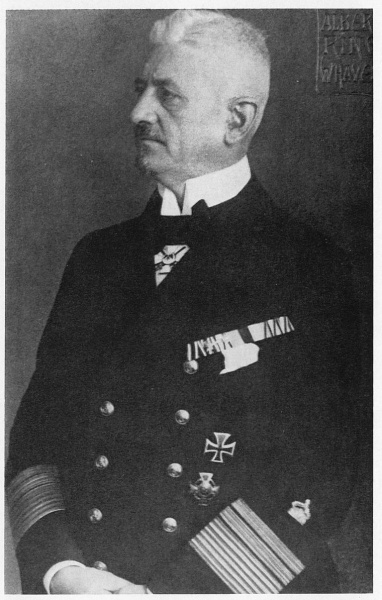

Ludwig von Reuter

All of this placed the commander of the interned ships, Ludwig von Reuter, in an unenviable position. Things were so bad that he had to temporarily transfer from the battleship Freidrich der Grosse to the light cruiser Emden because the crew had taken to stomping above his cabin throughout the night. The British found him very pleasant to deal with, and the Germans generally behaved themselves throughout the long months of captivity.

A panorama of the German fleet in Scapa Flow

But as his fleet's captivity approached the 7-month mark, von Reuter was faced with a dilemma. If the deadline for the signing of the treaty, set for June 21st, 1919, passed without the German delegation actually signing, the war would technically resume, and the British would undoubtedly act swiftly to seize the ships. In fact, the British had begun preparing boarding parties for just this eventuality, and even looked seriously at securing the ships on the evening of June 21st, but von Reuter, insulated from the radical changes taking place in Germany, became convinced that his government would never agree to the humiliating terms being proposed. As such, he quietly made arrangements to sink his own ships rather than letting them fall into British hands. Watertight doors were opened, and hatch covers removed. Ventilation ducts were opened up, and redundancies in the engineering plant were removed until only a single door stood between the interior of each ship and the waters of Scapa. The British failed to note any of this preparation because, as the ships were interned instead of being surrendered, they were still technically property of Germany and the British were not allowed to board them.

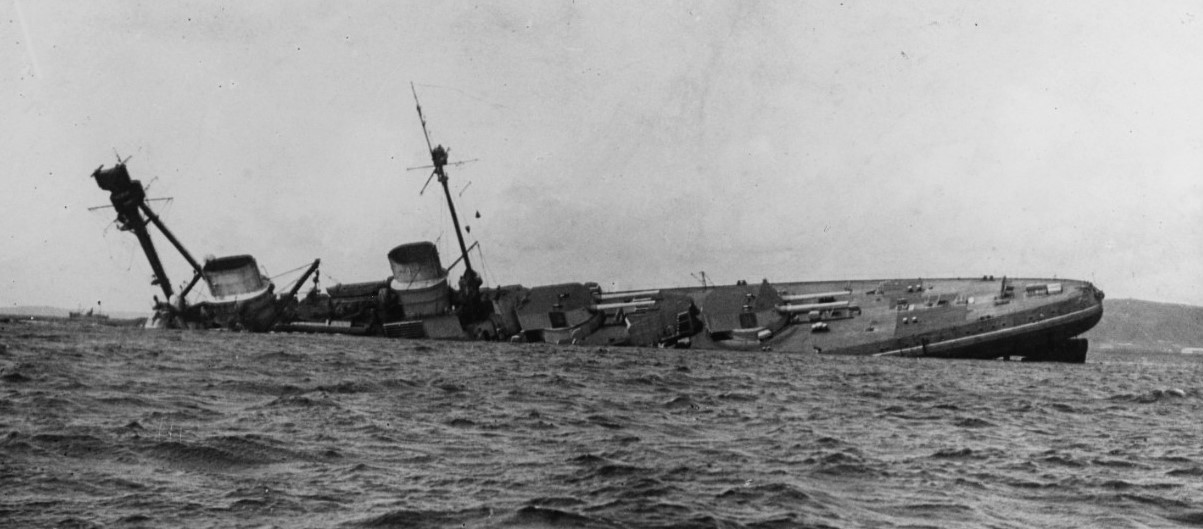

Bayern begins to list

Finally, June 21st, 1919 dawned. The original plan had been to sign the Treaty at noon, although the deadline had been extended by two days. Admiral Sydney Fremantle, commander of the Atlantic Fleet,1 had decided to take his force to sea for exercises. Von Reuter was apparently not informed of the delay,2 and at 1120, he signaled that all ships were to execute Paragraph 11 of the orders of today's date. The relevant paragraph discussed von Reuter's intention to scuttle the fleet, and the crews reacted swiftly, opening seacocks and readying for evacuation. At noon, it became obvious that something was wrong. Besides the settling of the ships, the German ensign was hoisted in violation of orders. Sixteen minutes later, Friedrich der Grosse rolled over and sank, the first of the German ships to go down.

Derfflinger minutes before she sank

A wireless signal was flashed to Fremantle almost immediately, and he suspended the exercise and turned for home. The remaining guardships at Scapa, mostly trawlers and other light ships backed by a few destroyers, tried to board the German ships and keep them afloat, or at least beach them somewhere shallow where they could be salvaged. Despite their efforts, by the time Fremantle returned at around 1430, most of the ships had gone down. Of the 16 capital ships, only Baden, Germany's newest battleship, had been beached, with the others lost to the deeps of Scapa. Four cruisers had gone down, with the other four beached. The only ships still properly afloat were four destroyers, while 32 were sunk and 14 had to be beached. By the time the last ship slipped beneath the surface, 400,000 tons of steel lay on the bottom of Scapa Flow, worth an estimated £70 million.3 10 of the Germans were killed and 16 wounded during the scuttling, all of them shot by the British to discourage them from abandoning ship, in the hopes that they would undo what they had done.4 They were the last casualties of the war. All of the Germans in boats were taken prisoner, and they were treated as POWs, although a good legal case could be made that they should be denied such protections. There was serious talk of prosecuting von Reuter, but he was eventually repatriated to Germany without any further trouble.

British Whaler Ramna, stranded on the hull of the German battlecruiser Moltke

In the aftermath of the scuttling, there was wide outrage that such a thing had been allowed to happen, compounded by the Atlantic Fleet's absence. The French and Italians were particularly incensed, as they had each asked for a quarter of the German ships. This would have seriously upset the balance of power in European waters, a major problem for the cash-strapped British. Some came to believe that the British had allowed the scuttling, or even encouraged it, but there is no evidence of this. It was still a tremendous relief to the British, although they were quick to condemn what they saw as treachery on the part of von Reuter and his crews. The Germans, on the other hand, saw the scuttling as having snatched back the honor that had been lost when the fleet sailed into captivity.

Baden and cruiser Frankfort aground

The remaining ships of the High Seas Fleet which had not been interned, including the first two German dreadnought classes, were divided up among the Allies. The British evaluated Baden, eventually expending her as a target, while the Americans received Ostfriesland as a prize, with Billy Mitchell famously sunk. During the 20s and 30s, most of the sunken ships were raised and scrapped, although the battleships König, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf, along with four cruisers, remain at Scapa to this day, where they are popular with scuba divers.

1 Two squadrons of battleships and one of battlecruisers, along with escorts. ⇑

2 Fremantle claimed that he did inform van Reuter, but von Reuter said that he didn't know about the extension until the evening. ⇑

3 This would be equivalent to £3.5 billion/$4.5 billion in 2019. ⇑

4 One of these was the captain of Markgraf, the second holder of that position to die in an odd way. One of his predecessors had been pushed over the side after a night of drinking while the ship was in Kiel. ⇑

Comments

Do the British retain ownership of the wrecks?

Low-background steel is important stuff, if you want to make certain precise instruments.

Actually, they're owned by a private individual who just put them up on ebay. They're scheduled monuments, so they can't be removed from the seabed, and AIUI ownership just means getting to give permission to go inside. It might be possible to get an exception if low-background steel was needed, but I think that the gradual decay of fallout from atmospheric nuclear testing, and improved instruments, have made it a lot less important.

Why did the Brits expend Baden when their inspection team concluded that Baden "considered as a fighting machine, anyhow on balance the Baden was markedly in advance of any comparable ship of the Royal Navy"?

Seems like if they kept it in service, Baden might have been useful in WW2. Imagine the Royal Navy sending it out to help Hood and Prince of Wales to fight Bismarck!

There are two problems with that. First, there's a well-known tendency for a large fraction of people to find the other side's equipment superior, even if sober engineering analysis shows otherwise. This appears to be the case with Baden. I'm sure there were a few details that the British adopted, but the overall design was probably inferior to British ships for British missions, particularly when you consider the rather different design standards of the two sides. Baden's quarters were so cramped that the British assumed that her crew normally lived ashore. They didn't, which may have had something to do with the mutinies. But such quarters would have been totally unacceptable in a British ship protecting a worldwide empire.

Second, there's the issue of keeping it in service. It's a German ship designed around German components, and keeping it around would have meant either finding a way to source those components, or refitting the ship with British equivalents. For instance, the guns on Baden were 38 cm/14.96", which means they probably couldn't have fired British 15" shells. They're also designed for German propellant, which means the chambers are about half the size of those of the British 15" gun. And they're 20% lighter, so you can't just replace them. Apply the same logic to every system onboard, and you see why using captured ships mostly went out with the age of sail. It's possible, and might be a good idea if you're way behind, but it certainly didn't make sense for Britain there.

Ah, that Slade article explains it pretty well. I've certainly fell victim to that temptation to think that the other guy has better kit before. Since the Soviets used HMS Royal Sovereign as Arkhangelsk and were planning to use the Giulio Cesare if it didn't hit a mine, I kind of assumed it wasn't that difficult. Perhaps the Brits would have made more of an effort if they weren't already decommissioning so many dreadnoughts after the Great War.

I've actually added this issue to my list of post topics. I don't know the details on Arkhangelsk, but in that case, the Soviets were probably getting support from the British. (Also, they didn't really use the ship. She was apparently returned in horrible condition, with live rounds rusted into the guns.)

Novorossiysk was used exclusively as a training vessel, and from what I recall, there were serious issues with keeping her operational. Neither of these (nor the few other cases of captured vessels being used, usually destroyers and the like being used as escorts) is going to need to be kept to the sort of standards you'd want in a front-line vessel like an operational battleship. And yeah, it's a matter of Britain being cash-strapped and keeping an Iron Duke under the Washington Treaty being a lot cheaper.

Why didn't the British demand immediate surrender of the ships? It's not like Germany could realistically have refused.

Diplomatic reasons. The norms of international diplomacy were taken rather more seriously in that era than they are today. The Armistice was just that, not formally a surrender. They did demand that the U-boats be handed over, basically on the grounds that unrestricted submarine warfare made them little better than pirates, but technically the fleet was still Germany's until the treaty was signed. The original plan was to intern them in a neutral country, but they couldn't find a host, so the British had to do it. Also, there was the tricky issue of who would get the ships after the treaty, and France and Italy were both suspicious of the British on that count, because of the potential for changes in the balance of power in European waters.

I had to look up low-background steel, and wiki says this (above the cut, even):

So it would seem they've already been picked over somewhat.

Actually, no. The last ship salvaged from Scapa was in 1939. Nicholas Jellicoe has a new book out on the scuttling, but I don’t have a copy yet. (USNI’s sloth in getting stuff up on its website is a rant that’s been building for the last couple of weeks.) The main source of low-background steel has traditionally been WWII-era ships that are being scrapped, although those have been rather thin on the ground since the 80s. There may have been some recovery of low-background steel from the wrecks in recent decades, but I’m not even sure of that. Another common claim is that the stuff in Scapa is particularly high-quality. This is true by WWI standards, but not by WWII.

What is the case to be made for German sailors being denied POW status?