In 1898, tensions between the US and Spain over the remains of Spain's Caribbean empire boiled over after the battleship Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. The US declared war and blockaded Cuba, while the Asiatic Fleet under George Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet in the Philippines at Manila Bay. The Spanish dispatched a fleet under Admiral Cervera to break the blockade, but it ended up trapped in Santiago on Cuba's south coast. The Americans landed troops and tightened their blockade, and on Sunday, July 3rd, Cervera finally sortied.

When Cervera's ships emerged from Santiago harbor, they found only five of the American heavy ships waiting for them. Massachusetts had been detached to coal at Guantanamo, while New York had recently departed to carry Sampson to a consultation with General Shafter, the commander of the troops ashore, leaving Commodore Schley in charge. Of the ships on station, only the Oregon had a clean bottom1 and steam up in all of her boilers, her engineering crew honed by her trip around South America. The other vessels had only enough power for 10 to 12 knots when the Spanish were sighted and Iowa ran up hoist number 250, "the enemy's ships are escaping" and fired the alarm gun. Two minutes later, her men were at their battle stations, many still wearing their white uniforms for Sunday inspection. New York, alerted by the alarm guns, turned back to join the action.

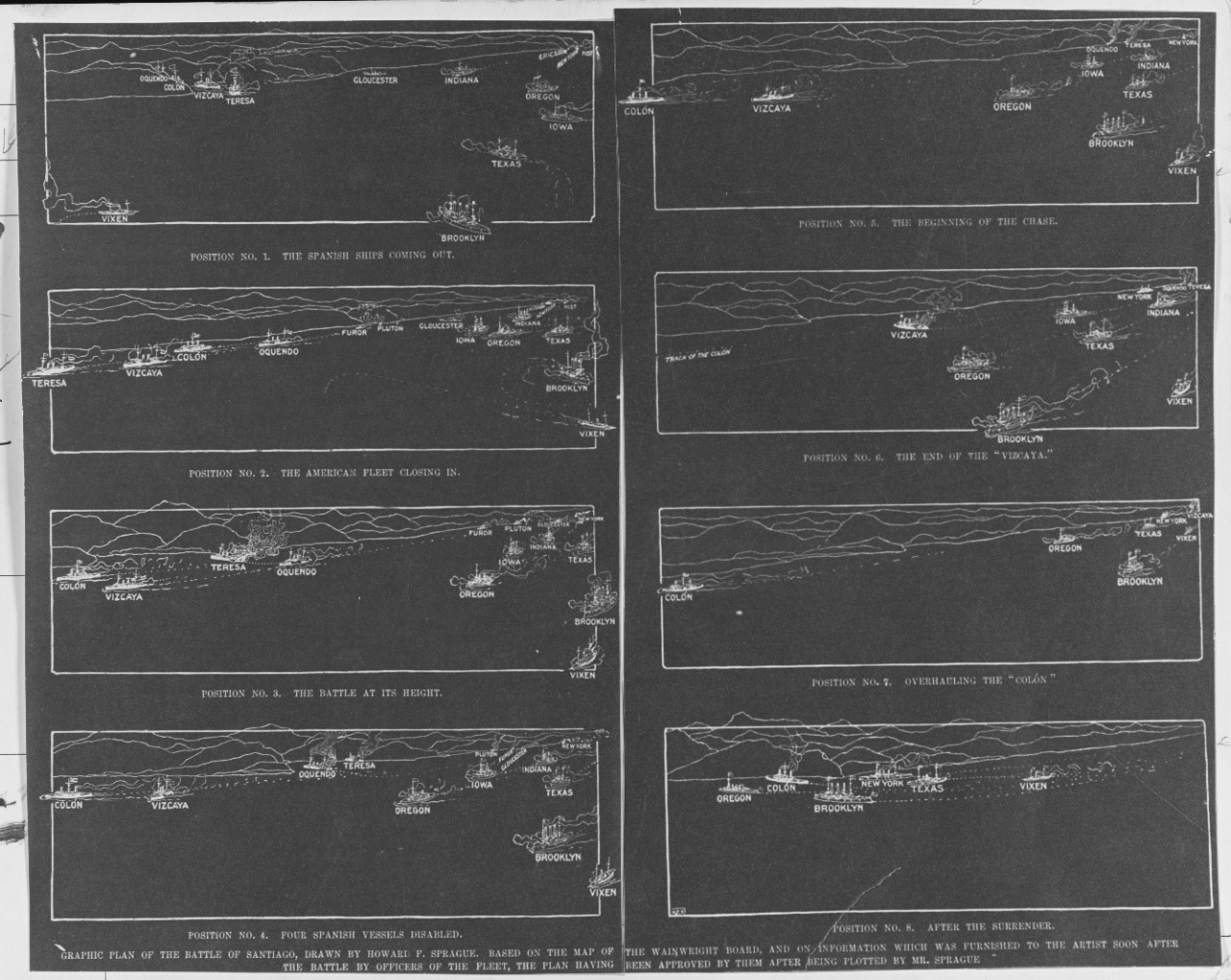

A set of maps showing the phases of the battle

The Spanish plan was to concentrate fire on Brooklyn, the westernmost ship of the blockade and the only one that, on paper, they couldn't outrun.2 Cervera's flagship, Infanta Maria Teresa, lead the way out past the Morro, followed by Vizcaya, Cristobal Colon and Almirante Oquendo at intervals of about 1000 yards. Behind them were the destroyers Pluton and Furor, who were supposed to hold off the battleships with their torpedoes. But this was thwarted by the quick reaction of the Americans, who opened fire at 0940, even before Teresa was able to turn west. The other three Spanish cruisers followed her, hugging the Cuban coast, with the American fleet in hot pursuit. Schley, aboard Brooklyn, ordered her to turn to port, taking her away from the Spanish and nearly colliding with Texas in the process. The Spanish destroyers were tardy in their appearance, and found the gunboat Gloucester waiting for them. Despite being heavily outgunned by the Spanish vessels, the rapidity and accuracy of Gloucester's fire soon gave her the upper hand. Both Spanish destroyers were shot up and ultimately sunk without doing any damage to the Americans.

Furor and Pluton burning after their engagement with Gloucester

Brooklyn, Oregon and Texas found themselves able to keep up with the fleeing Spanish cruisers, although it would take time to close the head start the Spanish had. The 11" guns on the fleeing ships fired more quickly than those of their pursuers, but the Spanish gunners always fired high, with many of their shells just missing Iowa. The American gunners were better, with an 8" shell hitting Teresa after only a dozen minutes, setting the flag cabin on fire and cutting the firemains. The Spanish had done a poor job of removing wood fittings and preparing the ship for combat, and the fire soon spread, driving men from the after guns and slowing the ship as smoke was drawn into the ventilation system. The American gunners soon found the range, and began to pound the cruiser mercilessly. Gunners topside were cut down by American 6" and 8" shells, and the torpedo flat3 was opened to the sea by heavy shells. When the fire aft began to threaten the magazine, Cervera ordered it flooded, but the smoke kept the crew from reaching the valves. Fearing an explosion, Teresa headed for shore, grounding only six and a half miles from the Morro castle at the entrance to Santiago Bay.

Men aboard Iowa watch the battle. Note the dense gunsmoke shrouding the ship in the center.

Oquendo was next in line to be pounded into scrap. Her forward turret was disabled even before she cleared the Morro, while a 14" torpedo was set off by another shell, wrecking the aft section of the ship. Soon, she was practically defenseless, with only two 14cm QF guns, starved of ammo by hoist problems, to face the fire of Oregon, Texas, Iowa and Indiana. With American shells passing all the way through his command, Oquendo’s captain decided that the time was right to follow Teresa’s example and beach his ship, having made it two miles further and having lost a quarter of his crew in the process.

One of Vizcaya's torpedoes detonates

Vizcaya, like Teresa, was soon set alight by a shell bursting amid the wood furnishings in her officer's quarters, and her efforts to fight the fire were similarly ineffective. With the demise of her two sisters, most of the American ships turned their guns on her, and the hail of small-caliber shells drove the crew from their stations. Within six minutes, Vizcaya was a charnel house, and her captain turned her for shore, having made only fifteen miles from Santiago in the hour and a half since the battle began. Destroyer Ericsson, which had been about to torpedo her, instead came alongside and plucked twenty men from her decks despite ammunition cooking off all around her. At this point, Iowa and Indiana were ordered back to Santiago, in case the Spanish tried to break something else out with the Americans distracted.

Brooklyn and Oregon pursue Colon

This left only Colon of the Spanish cruisers. She was by far the most modern of the four, so modern, in fact, that she lacked heavy guns. She did, however, have an armor scheme much better suited to resisting QF gunfire, fewer wood furnishings and the best engineering plant. She had made it through the initial barrage almost unscathed, and by the time Vizcaya turned towards shore, she had drawn out of range of her pursuers. However, at around noon, she ran out of good-quality coal, and the inferior fuel remaining slowed her,4 allowing Oregon, Brooklyn and the late-arriving New York to close the gap. At 1250, Oregon opened fire, and twenty-five minutes later, Colon's captain hoisted the white flag, despite having lost only a single man killed and sixteen wounded from half a dozen hits.5 He ordered the seacocks opened, and the breachblocks thrown over the side, measures which succeeded in putting Colon on a reef despite the best efforts of the prize crew from Oregon. She had run 55 miles from Santiago at an average speed of 13.9 kts, a reasonably impressive performance for the day. New York was ordered to push Colon into shallower water, as it looked like she could be salvaged, but despite excellent shiphandling, the Spanish cruiser rolled onto her side.6

American boats rescue survivors from Oquendo

After the battle, the Americans immediately set about rescuing the Spanish survivors, both from the water and from hostile Cuban guerillas who waited for any who made it ashore. Cervera himself was picked up by a boat from Gloucester, whose crew also boarded several of the Spanish ships to rescue anyone left aboard. The captain of Vizcaya, badly wounded, offered his sword to Captain Robley Evans7 of Iowa in the traditional gesture of surrender, but Captain Evans refused to accept it to the cheers of his crew. Most of the American ships took a few hits, but only one man was killed, Yeoman George Ellis of Brooklyn, who was decapitated by a Spanish shell. His body was to be thrown over the side, but Schley himself intervened and Ellis was buried with full military honors. The Spanish, on the other hand, lost over 340 dead.

Colon's secondary guns point at the sky after her capsize

The Battle of Santiago sealed the fate of Spain's empire in the New World. Not only did it destroy any chance of Spain breaking the blockade, it also freed the American fleet for operations elsewhere. Two weeks after the battle, the defenders of Santiago surrendered. But before we look at the last few naval operations of the war, we must turn our attention to the technical implications of the one-sided American victory, and to the hardest-fought phase of the battle, between Sampson and Schley for credit.

1 Before modern anti-fouling paints, marine fouling was a serious problem for ships. Cleaning off fouling was a very difficult task requiring drydocking, so ships often had to fight with dirty bottoms. ⇑

2 In practice, Brooklyn's speed advantage was minimal. Unusually, she was fitted with two engines per shaft for maximum speed, but would uncouple one of them for economy. While on blockade duty, she had only one coupled, limiting her to 16 kts, and coupling the other would require coming to a stop. New York had the same problem during the battle. ⇑

3 This is the term for the area where the underwater torpedo tubes are located. It was usually the largest underwater space besides the machinery spaces. ⇑

4 This was probably compounded by problems with her stokers. They had been on short rations, and while the brandy they were given may have allowed an initial burst of energy, it probably didn't help their long-term performance. Apparently, some even tried to mutiny and escape, and were shot by their officers. ⇑

5 The best justification I can see for this is probably the rapid deaths of the other cruisers, as Colon was seriously outgunned by the three ships closing in on her and I suspect the morale of her crew was not particularly high. Sometimes, the line between cowardice and moral courage is thin indeed. ⇑

6 An interesting footnote to the battle is the fate of the unarmored cruiser Reina Mercedes. Engine troubles forced her to be left behind at Santiago during the sortie, and she was scuttled in the channel on July 4th to prevent the Americans from entering. After the city fell, the Navy decided to salvage her, and was towed to Maine for repairs. She was ultimately commissioned as USS Reina Mercedes, and after plans to turn her into a training ship fell through, she served as a station ship at the Naval Academy until 1957, when she was scrapped. Until 1940, midshipmen being punished were required to live in hammocks aboard her, and she was the only ship where dependents were allowed to live, as the Captain's family had quarters aboard her. ⇑

7 Yes, this is the same Robley Evans who commanded the first leg of the Great White Fleet's cruise, but he was in good health at the time, and his reputation from the war probably helped him retain command for as long as he did. ⇑

Comments

The Spanish had done a poor job of removing wood fittings and preparing the ship for combat,

Why would you have naval ships that need their fittings removed to prepare for combat? Shouldn't they be prepared for combat, at least at the level of hardware and fittings, all the time?

The rest of the story: Ships running out of coal a couple of hours into a chase that they've prepared for over months. Stokers having no food except for brandy... This all sounds like the actual war was already won by the USA via logistical strategy and the actual fighting was just getting the Spanish to accept it.

I'm reminded of the Japanese actions at the end of WW2, when the story keeps being punctuated by "And then the Japanese ship ran out of fuel... the Japanese men had been living on 1/3 rations for 4 months at this point... the starving Japanese factory workers kept eating the glue they were supposed to be using to make the aircraft..."

A lot of it was habitability stuff. Things like furniture and excess clothing, which you need in peacetime, but which are hazards in wartime. Dewey stripped his ships rigorously before Manila Bay. I think some stripping was done off Santiago by the Americans. The Spanish should have accepted that their ships would be uncomfortable, but also less vulnerable to fire.

And yes, it was a logistical victory by the USN, although it's not as bad as late-war Japan was. They ran out of their best coal, not all coal, for instance.

...FWIW, one of Vizcaya's cannon survives as a memorial in - of all places - Public Square in my hometown of Cleveland, OH:

http://oosi.sculpturecenter.org/items/show/1497

What is the significance of refusing the sword of a surrendering officer?

It's essentially a means of honoring him. Traditionally, his sword would be taken as a trophy by the victorious commander, and handing it back is a way of saying "you fought very well and deserve to keep this."

"A lot of it was habitability stuff. Things like furniture and excess clothing, which you need in peacetime, but which are hazards in wartime"

Bad as this is in an ironclad, it was worse in the days of sail - the gun deck also served as the berthing deck for the crew, and you absolutely had to clear out their hammocks, etc, before you could ready the guns. And IIRC, standard procedure was to repurpose much of that as improvised barriers along the edges of the weather deck, to impede enemy musketry and boarding parties.

Strangely, none of the artwork of or depicting that era shows e.g. Long John Silver getting himself tangled up in someone's dirty long johns as he heroically buckles his swash aboard an enemy vessel.

I'm reminded of all the details Bean has regaled us with about how modern US warships have all the captain's cabin filled with finely crafted sheet metal furniture, carefully painted to look like wood, but safely fireproof.

p.s. You swash your buckler. Or rather swash someone else's buckler.