Communication between ships at sea has always been difficult. Unlike on land, sending a messenger is not usually very practical, so navies from the very earliest days have had to come up with other methods of passing messages.

The Battle of Salamis

The first recorded naval signal came during the Battle of Salamis, when an oar with a red flag attached was raised from the Greek flagship as a signal to stop luring the Persians deeper and instead launch the attack, which ultimately scattered the Persians and turned back Xerxes' invasion of Greece.1 And this set the pattern for operational signals for most of the next two millennia. The commander of a fleet would set up specific signals to support his plan, maybe declaring that a blue flag meant "attack the enemy" while a red flag meant "withdraw". Over time, some of these signals became traditional, and certain banners would be flown when a ship sighted the enemy, or when an admiral wanted his captains to come to the flagship for a conference. Sails were often used for signals, too, with the flagship letting fly the fore topsail being the traditional signal for the fleet to prepare to get underway.

A sailor fires a flare to signal at night

Of course, flags didn't work in all circumstances, particularly when the visibility was bad, at night or in fog. Guns, presumably firing blank charges, were commonly used for signalling in these conditions, although the vocabulary available was even more limited. Only simple signals, like "I have spotted the enemy" and "I am in trouble" could be sent. Lights could also be used at night, although they were only used in straightforward ways, like the ship nearest an enemy in pursuit showing a light in the stern to guide the rest of the fleet. Some of this was because the tactics of the day were very simple, and didn't require complicated signals to support them.2

Blake's flagship signalling in battle

In many ways, tactics and signalling evolved alongside each other, particularly as the line of battle developed under Robert Blake and his successors. Blake gave orders by hoisting five different flags from five different points on his ship, producing a total of 25 possible signals. Later, after the restoration of the monarchy, the future James II as Lord High Admiral took an interest in matters of signal, publishing the first signal book in 1673. However, over the next century, the number of required signals grew with the complexity of naval tactics, and by 1780, there were 50 flags in use for 330 signals. Worse, the flags were poorly designed, and it was often hard to tell the difference between them, particularly in poor lighting conditions.

Sir Home Riggs Popham

But help was at hand. Richard Howe, a British Admiral, had devised a new signal book in 1776, making use of only 21 flags, with each flag assigned a specific number. This meant that the flags could be carefully designed to make them easy to distinguish. Combinations of flags, known as hoists, were flown to indicate a page in the signal book and a specific signal on that page. However, there was still no real standardization, and each admiral provided his own signal code, which obviously caused great potential for confusion. This bizarre practice lasted until 1799, when the Admiralty finally intervened, adopting a standard signal code. This didn't stop private development of signals, and Captain Home Popham came up with an excellent elaboration on the previous codes, allowing about 30,000 words in 3 and 4-flag hoists, as well as assigning each flag a letter in case more words needed to be spelled. This was enough to give room for some rather unusual signals. Examples given in his code include "YOUR SISTER MARRIED TO A LORD OF THE ADMIRALTY" and "A CHANGE OF MINISTERS IS ABOUT TO TAKE PLACE". His system was the one in use at Trafalgar, when Nelson gave the famous signal ENGLAND EXPECTS THAT EVERY MAN WILL DO HIS DUTY.3

Victory flying ENGLAND EXPECTS THAT EVERY MAN WILL DO HIS DUTY

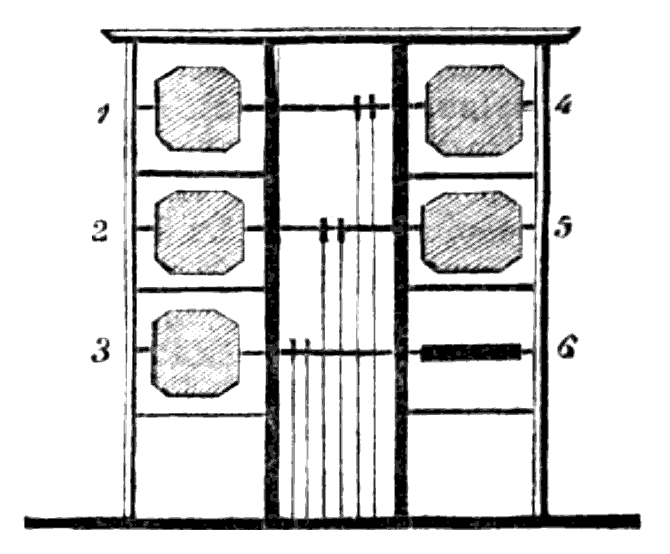

Flag signalling was not the only form of communications that Home Popham worked on, either. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French invented the semaphore telegraph, a system for very quickly relaying messages between stations on land. The Admiralty adopted a similar system, developed by Bishop George Murray, to transmit messages between the Admiralty and the major fleet bases. Each station consisted of six shutters that could be rotated to the horizontal or vertical position, allowing 64 different combinations. This system passed a message over the 69 miles from London to Deal in Kent in just 60 seconds. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Admiralty sought a better system, and selected the one devised by Popham, which consisted of a tall pole with two rotating arms, one at the top and one in the middle. His system remained in service until 1847, when the electric telegraph replaced it.

One of Murray's semaphore stations

While it was obviously impossible to construct long chains of semaphore stations at sea, the basic idea behind it was soon adapted into what most people think of when they hear the word semaphore, flag semaphore. This involved the use of two flags, with each letter and number assigned a certain position, allowing complicated messages to be passed much faster than was possible using flag hoists. This largely replaced the previous practice of passing detailed messages by coming close alongside another ship and shouting through speaking trumpets, except at night or when dealing with merchant ships, and was important enough that many warships of the late 19th century were fitted with mechanical semaphores in addition to hand-held semaphore flags, although even these still had a limited range. The end of that century saw the signal lamp become common, allowing the signalmen to pass information over even longer distances using Morse Code. These were bright enough to work reasonably well even in the daytime, and remain in limited use today because they allow communication even when ships are operating under radio silence. However, these systems still had limited range and generally were directed to a specific recipient, so flags remained in use to pass orders to the fleet as a whole.

A signalman aboard New Jersey uses semaphore to pass a message

So how did that process actually work? Let's say that an Admiral wanted to order his fleet onto a new course. He would give that order to his Flag Lieutenant, a junior officer who was in charge of his signal section.4 The flag lieutenant would find the appropriate signal in the book, and give orders to the signalmen5 to prepare the appropriate flags. They would get the flags out of the locker and attach them to the signal halyard, often set up so they could be hoisted folded and then broken to full visibility. The signalmen on the receiving ships would decipher the order from the flagship, then run up the same flags to signal receipt and give the flagship the chance to confirm that it had been received correctly. Finally, when the Admiral gave the order to execute, the flagship's hoist would be hauled down, synchronizing the maneuver throughout the fleet.6

An Iowa signalman passes a message using the signal lamp

Today, flag signalling has been largely superseded by radio in various forms, but it has remained in a few niches, when messages need to be longer-lasting that the instant transmission of radio. Flags are often flown with ship's radio callsigns, and for short messages, like Bravo Zulu, which means "Well Done". They are also used to indicate a vessel's status. For instance, the Bravo flag is flown by ships loading or unloading ammunition, while the Q (Quebec) flag is a request to the local authorities to certify the vessel as disease-free and allow it to dock. A Delta Flag indicates that the ship is having difficulty maneuvering, and that other vessels should stay away.

Flags are run up aboard Iowa in the 1980s

Despite the development of flags, and the skill of the crews in their use, something better was coming. Starting from the mid-1890s, radio went to sea, and would revolutionize everything.

1 Or so says my primary source, the book Make Another Signal. The wiki article mentions nothing of the sort, and other research casts doubt on it, but it's too good of an example to pass up. ⇑

2 Night signalling did become more complicated later on. By Nelson's day, it was a combination of guns, flares, and lights in specific arrangements on frames. In fog, only sound signals were used, including bells and horns as well as guns. ⇑

3 Nelson originally asked for ENGLAND CONFIDES..., meaning that England was confident, but his flag lieutenant pointed out that "confides" was not in the signal book, and would have to be spelled out by the use of letter flags, so "expects" was substituted. "Duty" was also missing from the book, but it was short enough to spell out. ⇑

4 The flag lieutenant is an interesting phenomenon. He was the Admiral's closest aide, and spent a lot of time with him and his family. There was a long tradition of Flag Lieutenants marrying the daughters of their admirals, which meant that they were often chosen (by the Admiral's wife) for their charisma and social graces more than their signal skills. This worked about as well as you'd expect when war broke out. ⇑

5 These were seen as the elite among the enlisted men, and subjected to rigorous testing. They also worked under the eyes of the officers, which increased their status. ⇑

6 This process had an interesting effect on the development of tactics, particularly in the RN, discussed in the excellent book Rules of the Game. ⇑

Comments

Seeing Popham's name brings to mind the "Popham Panel", a system of ground-to-air communication used from late WWI until the 'thirties. IIRC it consisted of canvas strips laid out upon a square. I can't find a really good Web cite for it, but I first came across it in Never Stop the Engine When it's Hot, David Lee's entertaining memoir of RAF duty on the North West Frontier.

I don't know whether the name came from using the Popham telegraphic encoding, or a metonymic reference to semaphore, or whether there was another Popham (a descendant?) with a similar aptitude for telecommunications.

Herodotus (8.84.1-2) mentions two different accounts: one where a single Athenian warship reversed and attacked first and the rest of the fleet took their cues from it, and one where a "phantom of a woman" shouted commands to the fleet loudly enough for all to hear.

The only other classical source I know of for the battle not derived from Herodotus was Diodorus Siculus, who is believed to have based his account closely on Ephorus of Cyme (writing a generation or two after Herodotus, who in turn wrote about a generation after the battle). Diodorus (11.18.6) doesn't mention a specific signal, just that "The Athenians, observing the disorder among the barbarians, now advanced upon the enemy".

I did come across a few variations of the Red Oar signal on google (most commonly a red cloak tied to an oar), but only from modern sources and never with a citation I can trace earlier than ~1970. It does make a better story than the classical accounts, and it makes more sense than either no signal at all or a signal shouted from an observer on shore, but I suspect it originated as speculation based on accounts of Cleopatra's fleet using red banners tied to the masts as signals.

The signal being shouted from shore seems plausible as well (not the phantom/ghosty-apparition part, but the signal itself). The straits are only about a mile across, and the Greek fleet had been retreating towards the beach of the Athenian-held island, so the could plausibly have heard a loud enough shout (although a horn or drum signal would seem more reliable). And both sources describe Xerxes observing the battle from the opposite shore, with Diodorus specifically crediting him with giving the order for the Persian fleet to attack (no mention of how the order was given, sadly).

Thanks for looking into that. It's rather interesting that such a tale could originate as late as 1970. But the basic concept is simple enough that it certainly dates back a very long way. I didn't want to spend huge amounts of time trying to run down the origins, because I'm not writing a book. (Yet. Nobody else has really done so.)

No worries. I looked into it mainly because I grew up with Larry Gonick's Cartoon History series, and he went with a variation of Herodotus's "Shouting from shore" account for his account of the battle. I'd never heard the red banner account before, and I was curious where it had come from originally.

If you've got the commanding King within site of the battle, I imagine they would automatically start using the same command methods they use for commanding their troops on land.

Of course I have no idea what methods the ancient Persians used for commanding troops, but banners and things being waved around seems to be a very early development. The Old Testament clearly mentions Moses holding his arms in the air to direct Israelite armies during battles. That was pre-Persian-wars.

A brief Wikipedia check shows a photograph of a Persian "flag", made from bronze, from the 3rd millennium BC. So LONG before Salamis.

(I volunteer NOT to be the guy who has to carry and wave a bronze flag.)

I've now remembered who the Popham of Popham Panel (probably) was: ACM Sir Robert Brooke-Popham.

I can't find out from a quick Wiki whether he was related to Capt Home Popham, but it's not impossible ;)