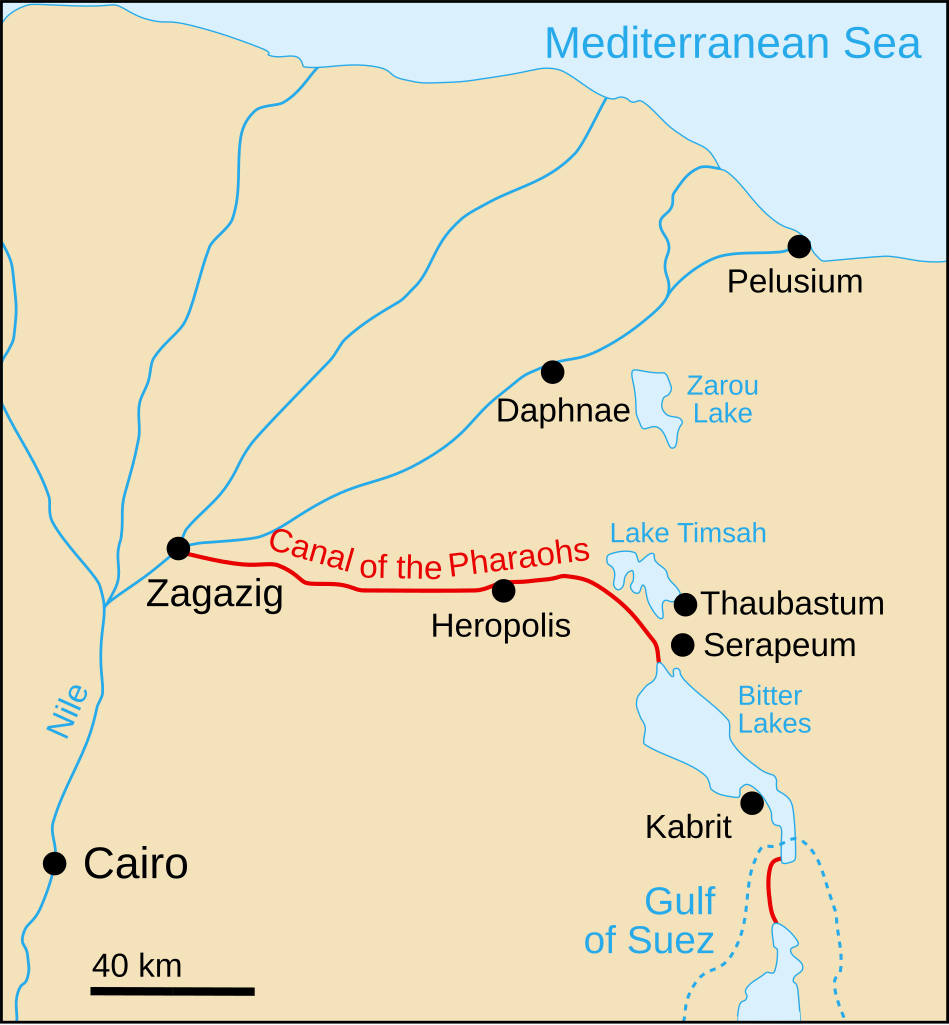

Man has traded across the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean for millennia, and with only a narrow stretch of land separating the two, the idea of completing a water connection between the two was equally ancient. In fact, the ancient Egyptians dug a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea, although the history of the so-called "Canal of the Pharaohs" is rather unclear. What is clear is that the canal was repaired and closed several times before finally being shut in 767 during a rebellion in Muslim-controlled Egypt.

The route of the Canal of the Pharaohs

For the next millennium, cargo traveling through the Red Sea crossed the isthmus of Suez by camel caravan, and the canal was largely forgotten until the French revolutionary government, in a Churchillian move, decided that the best way to attack the British was to have Napoleon invade Egypt. The expedition had a number of goals, including an offhand reference to cutting the isthmus of Suez, and it included a large contingent of academics, whose work laid the foundations of Egyptology. Their discoveries kicked off a mania for all things Egyptian that lasted through most of the 19th century, but those tasked with making a survey of a direct canal route made a mistake in their calculations, believing the Red Sea at high tide to be about 30' higher than the Mediterranean.

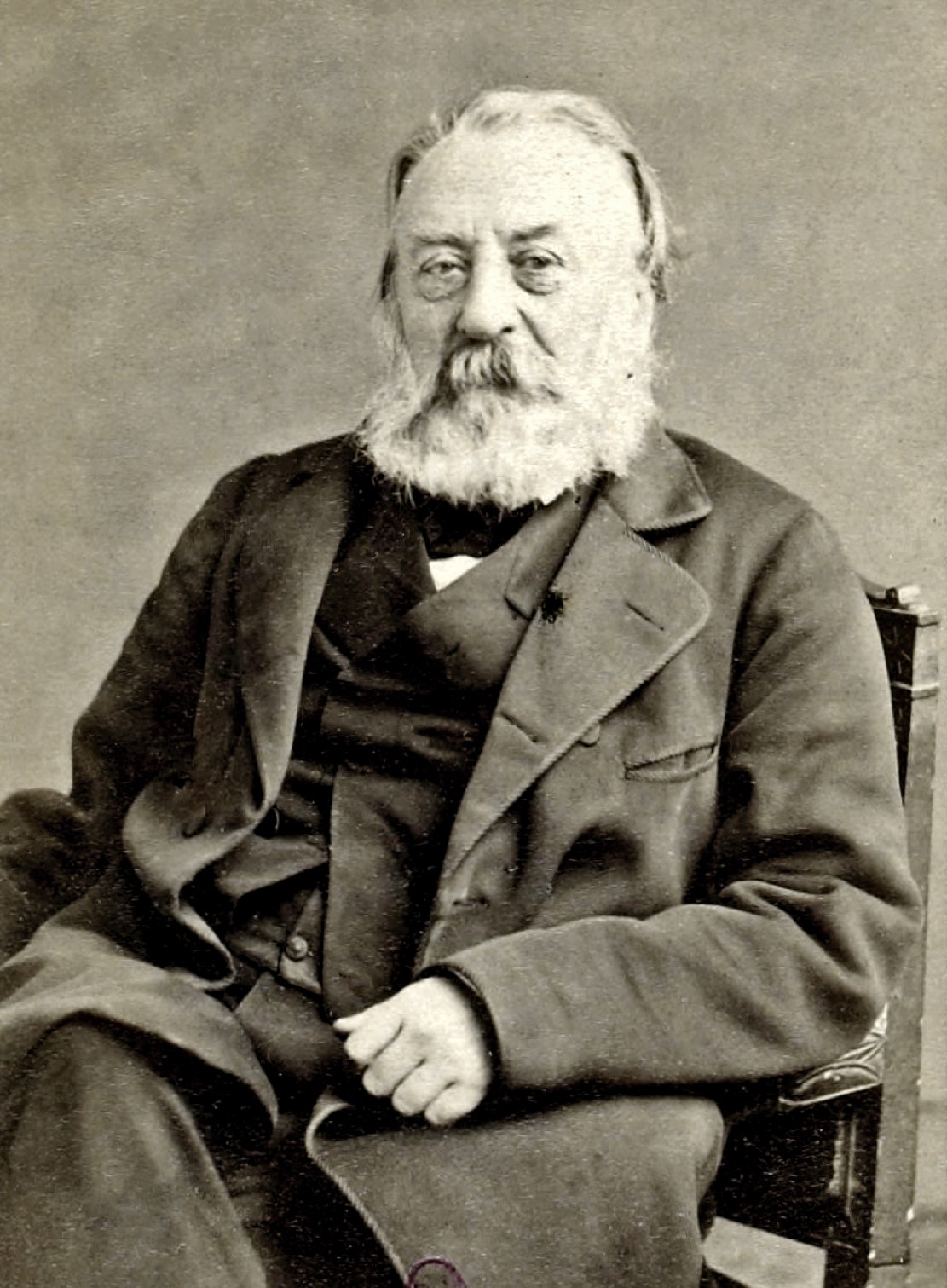

Muhammad Ali

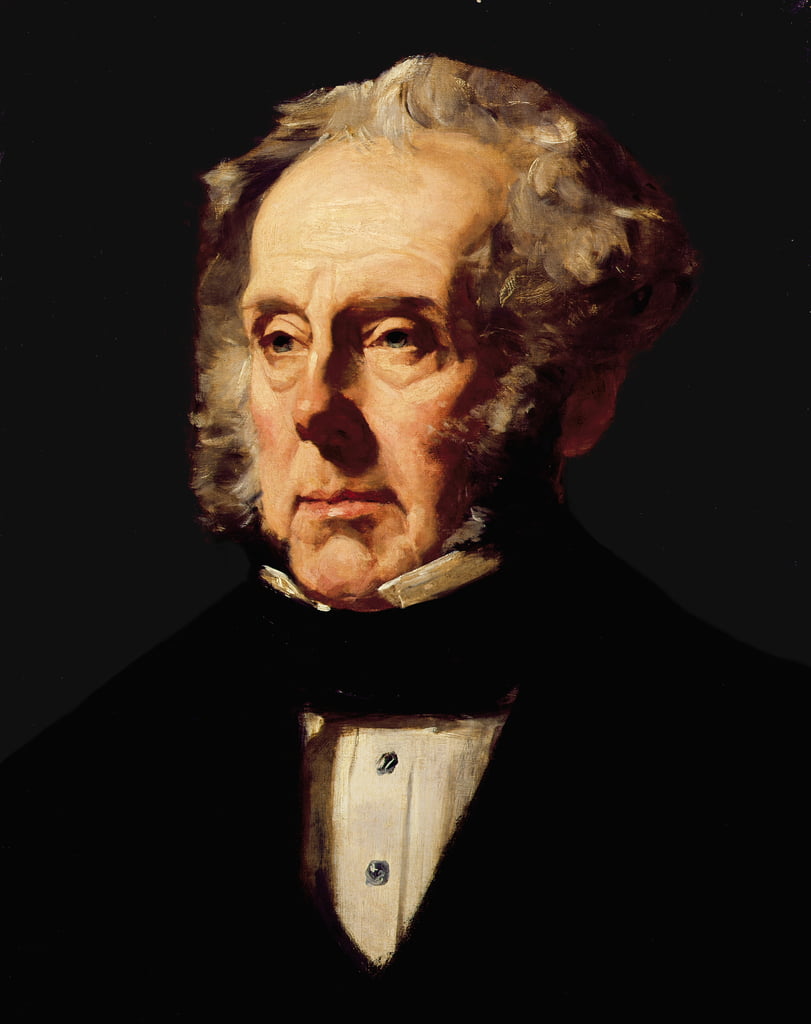

Napoleon soon left Egypt, returning to France to stage a coup and make himself Emperor. The vacuum left behind was filled by an Albanian mercenary, Muhammad Ali,1 who quickly set about modernizing the country and the army in an attempt to maintain its independence in the face of European powers poised to divvy up the globe. While he did that, a French thinker by the name of Henri de Saint-Simon, inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution, was planting seeds that would blossom in the Egyptian desert.

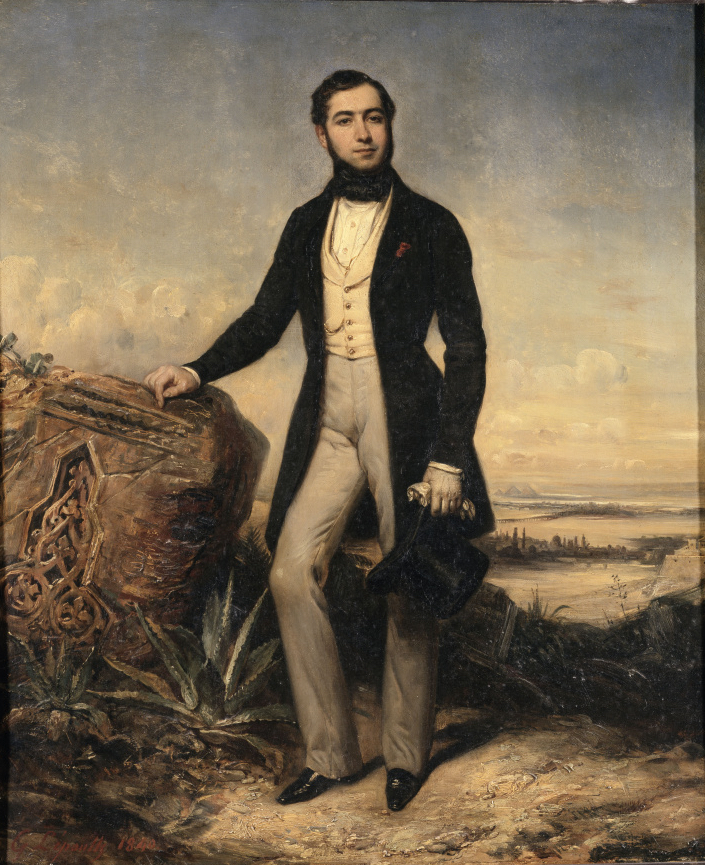

Barthlemy Prosper Enfantin

Saint-Simon was a relentless advocate for progress, calling for the reorganization of society under the control of scientists and engineers, as well as a number of mystical ideas, culminating in a proposal for a "New Christianity", which would be focused on making the present world better. One element of all of this was a passion for canals, the easiest way to transport goods in a world where railroads hadn't been invented. After his death in 1825, one of his disciples, Barthelemy-Prosper Enfantin, took over most of the movement, proclaiming a type of meritocratic, utilitarian socialism. He also ran with Saint-Simon's mysticism, proclaiming that the problems with the world were the result of dualistic tensions, between Man and Woman, Material and Spiritual, West and East. Only his ideas could marry the two sides of this dichotomy, and a marriage that would be physically consummated by the completion of a canal at Suez.

Despite his rather unusual ideas, Enfantin attracted a number of followers, some of them skilled engineers, and in 1833, he set off for Egypt to offer his aid to Muhammad Ali in his quest to modernize Egypt. It took months to gain access to the pasha, who turned down plans for a canal, fearing it would cut into the customs revenue generated by transshipment of goods between Alexandria and Suez, but agreed to let the Saint-Simonians set up irrigation works in the Nile Delta. But a more consequential meeting had already taken place in the months that Enfantin waited, when he had shared his ideas with a young French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps.

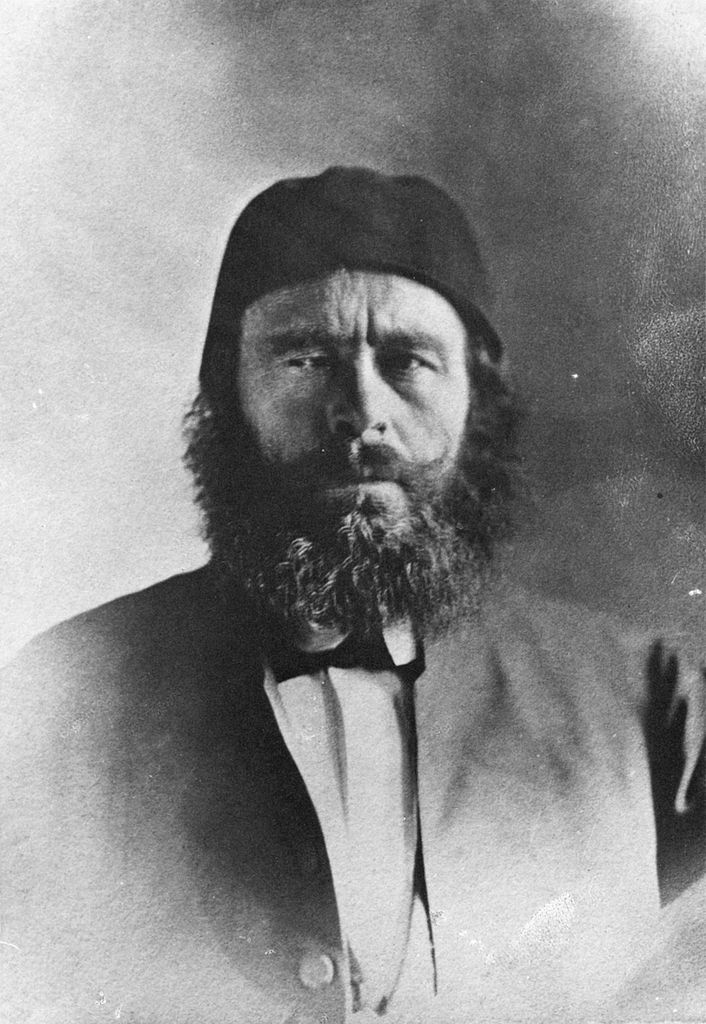

A young Ferdinand de Lesseps

De Lesseps was a driven and ambitious man, and in 1835, he became French consul to Egypt, growing close to Muhammad Ali's son Said. This was an important post, as the French backed Egypt in opposition to British support for the Ottoman Sultan, Ali's nominal overlord. Egyptian modernization was starting to pay off, leading to several wars where the Ottomans were defeated, only to be saved by British intervention. In 1849, Muhammad Ali died, and de Lesseps, now posted to Italy, found himself scapegoated for changing French policy in the region, bringing his diplomatic career to an end.

Abbas

The previous few years had seen significant progress on the Canal plans. Enfantin had returned to France in 1836, where he had made a fortune off the construction of the French railroad network. Some of this money was allocated to a committee to study the possibility of a canal at Suez, and in 1847, their survey had revealed that the sea level was the same at both ends. Despite this, Enfantin backed a canal that broadly followed the route of the Canal of the Pharaohs, essentially for political reasons. Before they could persuade Muhammad Ali, he passed away, leaving Egypt in the hands of his grandson, Abbas.2 Abbas feared European influence, and closed Egypt to foreign business until his assassination in July 1854. This opened the door for de Lesseps, whose troubles had been compounded by the death of his wife a year earlier. He wanted a grand project, and the Canal was an obvious choice with Egypt now ruled by Said, a Francophile who he knew reasonably well. De Lesseps quickly sent off a letter, promising Said both glory and a financial windfall. Said was intrigued by the proposal, and invited him to Egypt to discuss the plan in more detail. Despite his status as a private citizen, he was received as an important dignitary, a result not only of his former diplomatic rank and friendship with the pasha, but also because his cousin Eugenie de Montijo had recently married Napoleon III, Emperor of France since 1852. De Lesseps was at his most charming, and during a trip into the desert, convinced Said to back his canal plan, one of many risky schemes he would authorize while in control of Egypt, a tendency that would ultimately deliver Egypt into the hands of the European powers.

Said

De Lesseps immediately faced several challenges. First, there was the question of the route. De Lesseps favored a plan that would first involve building a small canal from the Nile, to irrigate land that would be turned over the Canal Company under the deal he had made with Said and to provide water for the work of digging a direct canal. Others, Enfantin among them, favored the indirect route, and the battle between the two was as much over who would get credit for the canal as it was on the technical merits. De Lesseps was primarily motivated by the glory to be found in uniting the seas, and he fought bitterly with Enfantin over who would lead the project, eventually winning out and sidelining the Sanit-Simonians.

Second, there were diplomatic questions. Said was still technically a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, and while the Ottomans didn't have strong feelings either way, their British patrons certainly did. The Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, was focused entirely on the good of the British Empire, which he saw in sharply zero-sum terms. The benefits of the Canal to Egypt and France were obvious, which meant that the British must lose somehow, resulting in his vocal opposition to the project. Official British opposition was more constrained due to the alliance with France in the ongoing Crimean War, while de Lesseps took the position that Said didn't really need the Sultan's approval for the Canal, although it would be nice to have. He also took his case directly to the British people, arguing that the Canal would benefit the rulers of India more than anyone else, and that he desired an international canal, not just a French canal.

Lord Palmerston

The political problems occupied de Lesseps for almost four years as he shuttled among the capitals of Europe, reassuring Said, shoring up French support and wearing down the British and Ottomans. An engineering report issued in 1856 affirmed the viability of the direct route and quickly became a vital weapon for de Lesseps. And his campaign in Britain was bearing fruit, with public support undermining Palmerston's opposition even before the 1857 rebellion in India emphasized the utility of a shorter sea route to the subcontinent. Elsewhere, he insinuated that he was an unofficial envoy of Napoleon III, which wasn't entirely true. The French Emperor personally favored the canal but was unwilling to lend de Lesseps official sanction. However, he also didn't disavow him. Finally, Palmerston was temporarily neutralized in early 1858 when his government fell in the aftermath of an assassination attempt against Napoleon III, leaving the way open for de Lesseps to issue stock and actually start digging.

The normal procedure would have been to arrange financing through the great banking houses of Europe, but these, like the Rothschilds and Barings, would have wanted the usual 5% fee, which de Lesseps refused to pay. He would instead issue stock to the middle class of many nations as befitted a "Universal Company". Unfortunately, when the stock issue closed in November 1858, only the French had invested more than a token amount, and Said, who had agreed to buy any unsold shares, ended up taking three times the amount he had originally intended. But de Lesseps now had his money, and work could begin. In April 1859, he made the ceremonial first blow of the project with a pickaxe. This wasn't quite enough to deal with all of the diplomatic obstacles, which were finally resolved when de Lesseps managed to convince Napoleon III to officially back his enterprise and the Ottomans decided not to test their ability to issue Said orders. But while De Lesseps was finally free to start building, he had no idea what obstacles would pop up during the actual construction. We'll take a look at those next time.

Comments

Oh, well done! Looking forward to the next part.

Also - while we're in that part of the world, any thought about doing the naval aspects of the Derna Expedition?

Mike

Probably not. I did a brief overview of the Barbary Wars early in the year, and didn't see anything which really grabbed me to go deeper.