In the Autumn of 1940, the British Mediterranean fleet faced a serious problem. They had been dealing with the Italians since the collapse of France in June, and while they had managed to get the better of their enemies at Calabria back in July, the Italians had since managed to keep the RN from interfering too much with the convoys supporting the fighting in Libya.

HMS Illustrious

Something needed to be done to resolve the stalemate, and the British decided to finally put into practice an idea they'd been kicking around for a quarter-century. During WWI, British frustration over the reluctance of the High Seas Fleet to come out and fight had prompted studies of attacking the fleet in port using ship-launched aircraft. That war had ended before the plan had been carried out, but the concept had been remembered, and the development of shipboard aviation in the interwar years had made it genuinely practical. The Italian battleships were based at Taranto, on the instep of the Italian boot, and a strike by torpedo bombers flying from the carriers Illustrious and Eagle should be enough to shift the balance of power decisively in favor of the British.

This attack posed several serious problems. First and foremost, the only available aircraft were the Fairey Swordfish biplanes, and while the "Stringbag" had an enviable reputation for toughness, it was only fast by the standards of 1918 and the defenses around Taranto would undoubtedly slaughter the attackers if they approached in daylight. The alternative was to attack at night, despite the lack of experience with night carrier operations. Moonlight would help make up for the lack of the sun, and flares would be dropped over Taranto to give the attacking pilots better visibility. A few dive bombers were also added to the attack plan to help confuse the defenses. Second, the ships were anchored in approximately 40' of water, which meant that there was a serious risk of the torpedoes going too deep and ending up stuck in the mud. Tests showed that this wasn't an impossible problem to solve, so long as the torpedoes were dropped carefully and in their low-speed setting, which minimized the depth they would plunge to.

A torpedo is loaded on a Swordfish aboard Illustrious

The original plan was to carry out the attack on October 21st, the first day with a suitable moon, but while mechanics aboard Illustrious were fitting one of the Swordfish with a long-range fuel tank, a fire broke out, destroying two planes and forcing the operation to be delayed. Instead, it would be carried out on November 11th as part of a broader series of operations throughout the Mediterranean. The delay allowed more reconnaissance flights, which discovered the presence of barrage balloons over the anchorage. Unfortunately, these pictures had been taken by the RAF, and they refused to make copies, forcing the fleet intelligence officer to steal the photos, get them copies by the photo lab on Illustrious and return them the next day, with the RAF none the wiser. The last change took place just before the fleet sailed on November 6th. Eagle's avgas system had begun to develop problems, purportedly due to the number of near-misses she had suffered from Italian bombs, and she was left behind, with some of her aircraft transferred to Illustrious.

This brought the total number of Swordfish aboard to 24, which would be split into two strikes because of the limited ability of Illustrious to launch aircraft. Essentially, all aircraft to be launched at a given time would need to be on deck at once, ranged on the aft end of the flight deck. The number that could be ranged at once was limited by the deck length required for the first aircraft to take off, and thanks to a very long rounded section aft, Illustrious could only range a dozen Swordfish at a time. Six in each launch would carry torpedoes, and two would be loaded with flares and a pair of 250 lb bombs, while the balance would have half a dozen bombs of that weight for the dive-bombing attacks. The dive-bombers absorbed the losses when three Swordfish were lost while flying anti-submarine patrols en route, although all three crews were recovered. An investigation turned up that all three had been refueled from the same fueling point, which was connected to a tank that was contaminated with water. The other aircraft that had used this point had the fuel systems carefully cleaned out, allowing them to participate in the strike.

A Swordfish in flight

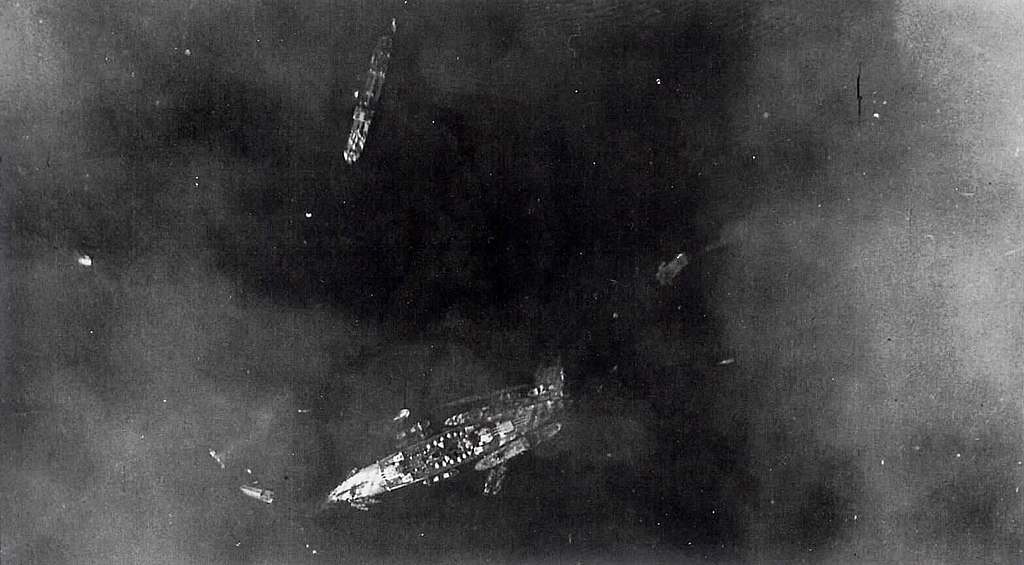

At 2035 on November 11th, Illustrious and her escorts began to fly off the first range of 12 Swordfish 170 nm southeast of Taranto. The Italians, lacking radar, relied instead on sound detectors1 and picked up the approaching torpedo bombers at 2250. Several batteries of guns began firing barrages, which served as a helpful guide for the British pilots. At 2302, the first flares were dropped, illuminating all six of Italy's battleships anchored below. The flares drifted over the harbor, and at 2315, the torpedo pilots judged the illumination suitable and began their runs. The lead aircraft chose Cavour as its target, dropping its torpedo 700 yds out and only 30' above the water. Unfortunately, it then flew between two destroyers and was shot down, although both crewmen survived and were treated as heroes by their captors. The next two planes also went after Cavour, but they approached from a different angle and both torpedoes missed. The following pair split up, closing in on Littorio from both north and south. Both hit, one on the port quarter, the other the starboard bow. The last Swordfish targeted Vittorio Veneto, but her torpedo seems to have hit the bottom short of the target.

While the torpedo bombers pumped their deadly fish into the Italian battleships, the dive bombers searched for targets overhead. The two flare-dropping aircraft struck the base's oil tanks, setting them on fire, while another attacked a nearby seaplane base and doing significant damage. The last three went after the cruisers moored by the town of Taranto, but made only one hit, and that a dud. By 2335, the 11 surviving aircraft were retreating to the south, although the noise of the second wave kept the Italian gunners firing their barrages.

This wave had begun to launch at 2120, but while the eighth aircraft was being moved into position, it collided with the ninth and last, cracking a pair of the latter's wing ribs. The damaged plane was quickly struck down into the hangar for repairs, getting airborne just after the rest of the group set off for Taranto at 2145. En route, the long-range fuel tank the torpedo-armed eighth aircraft carried developed a problem it was forced to turn back, the only failure of such a tank on any of the attack aircraft.

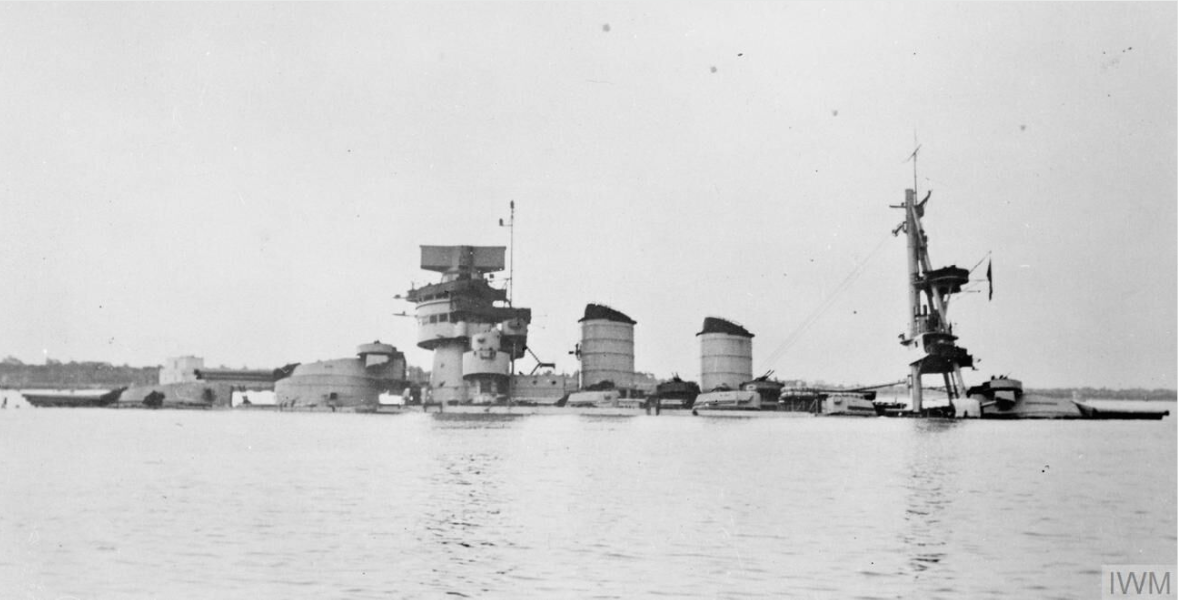

Cavour after the attack

Despite this, the other aircraft pressed on, and the flare-droppers began their work minutes before midnight, clearing the way for the first pair of torpedo bombers. These bored in on the damaged Littorio, with one torpedo hitting the starboard bow, the other burying itself in the mud under her keel to be retrieved by the Italians later on. The third, lining up on cruiser Gorizia, was shot down, killing both of the crew. Duilio was the target of the fourth Swordfish, and its torpedo ran true, hitting her to starboard abreast B turret. The last pilot planned to aim his fish at Vittorio Veneto, but a bullet hit on an aileron rod sent the Swordfish out of control. He regained control, but the situation probably contributed to the fact that he missed. Overhead, the two flare droppers added their bombs to the conflagration around the oil depot, while the dive bomber, the last plane off the deck, attacked cruiser Trento, but the bomb failed to detonate. Then it was time to turn for home, with the problems of navigation being greatly mitigated by the carrier's homing beacon, which would guide them in if they could get within 50 nm. All of the airplanes landed safely, and Illustrious turned south to rejoin the rest of the fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean. A second strike was planned for the next day, but worsening weather forced it to be called off, much to the relief of the crews.

Littorio surrounded by salvage tugs

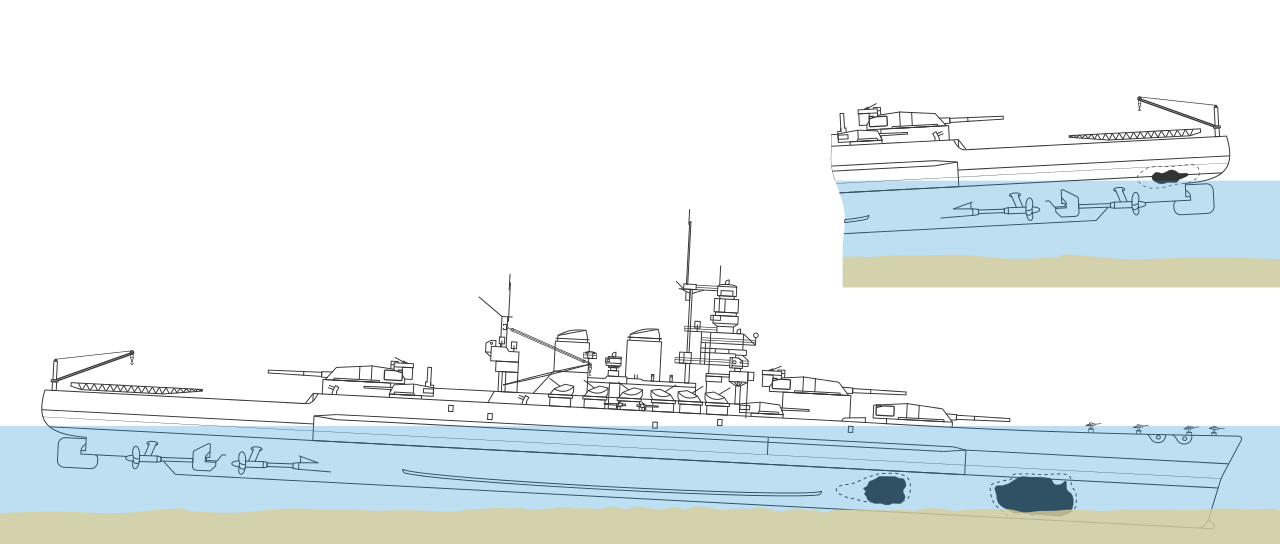

The results of the operation were dramatic. Although Cavour and Duilio had taken only one torpedo each, they had been equipped with magnetic pistols and had run under the battleships, completely bypassing their torpedo defenses and opening their hulls. Littorio had taken direct hits, and while the first explosion had been largely contained by her TDS, the other two had struck outside the protected area, causing extensive flooding. All three were clearly in danger of sinking, and they were swiftly towed into shallow water to help contain the damage. Littorio and Duilio came to rest with their bows on the bottom of the harbor, but most of their length stayed afloat, and they were raised and sent for repairs within a few days, returning to service in March and July 1941 respectively. Cavour was more badly damaged, and despite the best efforts of the Italians, she sank completely, with her main deck entirely submerged. It took until July 1941 to refloat her, and repairs continued through June 1943, with an estimated six months left to go when work was suspended. Instead, she would be taken over by the Germans after Italy surrendered, and eventually scrapped postwar.

The damage to Littorio

Strategically, the raid was a complete success. At the cost of two Swordfish, the Royal Navy had managed to cut the Italian battlefleet in half, and forced the surviving ships to move to more northerly ports, further away from the seas under contention. More than that, Littorio, Duilio and Cavour were the first battleships sunk by air attack, and the strike itself was by far the most efficient use of aircraft against battleships in the war, sinking one vessel for every four attacking aircraft, a measure only ever approached by the attack on Roma. The effectiveness of the raid is often credited with inspiring the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, although plans for such a raid had been proposed months earlier, and it more likely simply served to help sell the plan.

1 I don't have any details on these, but assume they were probably similar to the British acoustic mirrors. ⇑

Comments

Wait. Working magnetic pistols? WTF…

Where is the footnote?

@Tony

That's what my sources said. I was surprised, too.

And footnote should be fixed now.

I'm glad the Italians were such good sports about the whole thing.

The round downs are just... so frustrating. Granted that many things about the RN's armored flight deck carriers are frustrating, but the round downs seem almost spiteful. Like the naval architects were saying, "Fine! Look at this! See, we wouldn't want to operate a reasonably-sized air group anyway, even if we could somehow get our hands on a useful number of aircraft! So nyah!"

I'm pretty sure it was an aerodynamics thing. The British used a much shallower approach than the USN did, which placed a greater premium on operating in smooth air. This wasn't a minor problem, either. Through the 30s, you had slow airplanes that were relatively light by later standards, which meant they were very vulnerable to turbulence. I'm pretty sure this is why the angled deck didn't show up earlier, either, because that has you flying through the wake coming off the island.

@Tony The Royal Navy wasn't saddled with the Bureau of Ordnance. Additionally, this strike took place relatively close to the place where the Royal Navy developed and tested its magnetic pistols, so the Earth's magnetic field in the field was not too different from where they were prototyped.

@bean,

Of course. But you'd think somebody in the RN would have asked whether that was really needed anymore as the 30s drew to a close and aircraft were clearly only getting heavier. Certainly the fact that the round-downs went away almost immediately once the RN started trying to fix the Illustrious class and their successors suggests that by mid-war whatever desirable attributes they might previously have conveyed were no longer considered a worthwhile exchange for so drastically reducing both the number of aircraft carried and the number it was practical to operate.

Thus frustrating.

I have sat in a WW1 acoustic mirror on the east coast of England. Was advised by locals that they work well enough that you don't want to be in one when jets go supersonic over the North Sea

I'm thinking more about the magnetic torpedo pistols, and notice that I am confused. It seems really odd that both of the older battleships had the magnetic pistols work properly, while Littorio took three contact hits and didn't have a single torpedo go under her. I checked, and it's not that she drew any more water than the other ships. The information that there were magnetic pistols and they worked comes from Bagnasco & de Toro, while my other main source, the David Hobbs book on Taranto, left me with the impression that all of the torpedoes detonated on contact. Also, if the harbor is only 40' deep and the ships draw 33', why would you set the torpedo that deep? I am genuinely unsure what was going on.

Like Supermarina... :-|