I've just announced the 2026 Naval Gazing meetup at the Air Force museum in Dayton, Ohio. As part of that, I am preparing an introduction to aviation tour, and figured I should give a sneak peak of that for anyone who is on the fence about going.

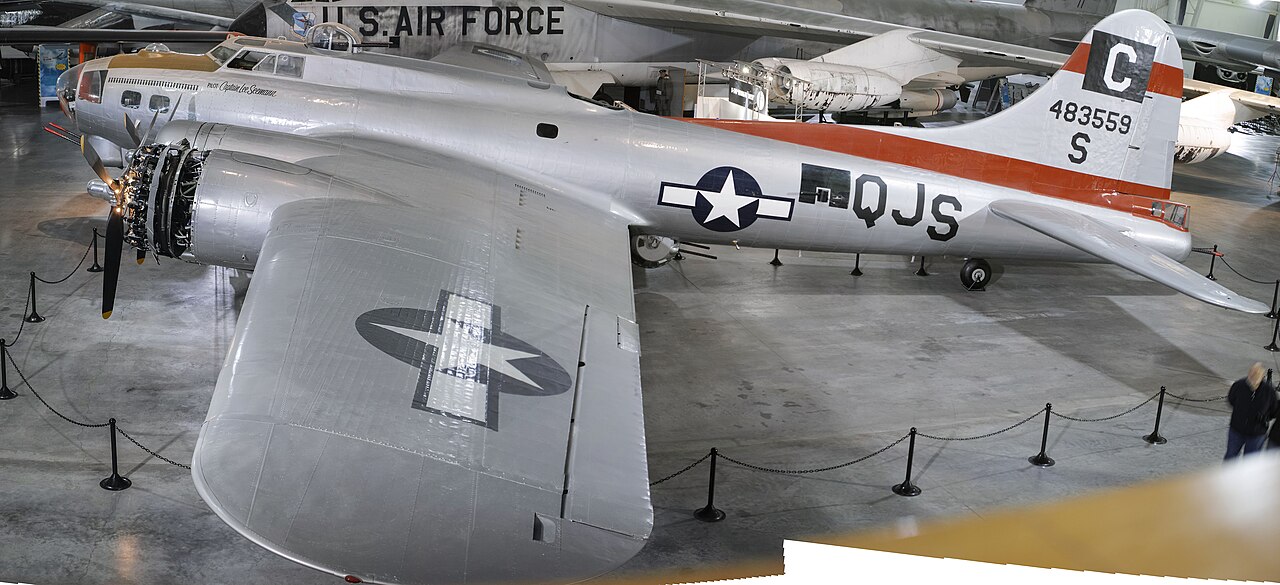

A fuselage

I should start this tour by explaining the basic parts of an airplane, so you understand what I'm talking about as we go along. We'll start with the fuselage. This is the tube in the center, and it's the most important part for two reasons. First, it serves as the backbone to hold all of the other pieces together, and if you take it away, you just have a pile of parts. Second, all planes exist for a reason, and that reason is usually found in the fuselage.1 Now, for military aircraft, there are four basic roles, and all operational military aircraft fulfill one or more of these. First, handling information, which covers everything from flying over to see what's going on down below to carrying a big radar to detect and direct other planes to trying to jam enemy radar. Second, attacking things on the ground, be it factories or ships or tanks or whatever. Third, moving people and stuff around, because you would really rather it be somewhere else quickly. And fourth, attacking planes that are doing something you don't like. I put this one last because it ultimately exists only to support the doing of the other three things, or to stop the other guy doing them to you. No matter how much the Air Force might try to deny it, aviation ultimately exists to produce effects on the surface. Now, note that this only applies to operational aircraft, and there are two types of planes that militaries do operate which don't fit into this schema: trainers, which you use to teach pilots how to fly, and experimental planes that push forward the science of aeronautics.

A wing with engines

But of course a fuselage by itself is just going to sit there, and that's not really all that useful, or if it is, it's not a plane. So we next need the thing that actually makes it a plane, wings. Wings are magical devices that generate a force called lift when air moves past them.2 Lift is one of the four fundamental forces of flight, and it opposes the second force, weight, which happens automatically. The amount of lift a wing produces varies with its size and shape and with what is called "angle of attack", basically the angle between the wing and the air flowing past. More angle of attack means more lift, at least up to a point, where the air stops sticking to the wing and lift drops a lot. This is called a "stall" and it's generally considered to be a bad thing, because lift dropping means the plane does, too. Nor is this the only example of air's treacherous nature. The pressure on the top of the wing is lower than on the bottom, and air would really like to flow from high pressure to low pressure around the tip of the wing, but this is bad for generating lift. This in turn means that a longer, thinner wing will generate a lot more lift per unit area than a short, stubby wing.

As required by law and custom, Forces on an aircraft

But getting a wing to generate lift requires it to be moving, which in turn requires our third force, thrust. This brings us to the engines, which are devices that convert liquified dinosaurs into backwards-moving air, either by means of a propeller, which is basically a giant fan, or a jet engine, which sucks in air, lights it on fire, and spits it out the back. Each has its pluses and minuses, but that's a topic for later. These are necessary because of air's ultimate treachery: the fourth and final force, drag. Drag tries to slow down anything moving through the air, and while streamlining the plane helps a lot, there are limits, particularly because generating lift also inherently produces drag.

Tail surfaces with controls

Now, a careful observer will notice that there are some other bits on a typical plane that are not fuselage, wings or engine. We'll start with the tail, which is also sometimes called the empennage due to the pernicious influence of the French on aviation vocabulary. There's the vertical stabilizer, which produces lift if the plane is flying to one side or the other, and the horizontal stabilizer, which produces lift if the plane is flying at the wrong angle of attack. Because this lift is at the tail, if the nose goes up, then there's more lift in the back and it pushes the nose down, and vice versa if the nose is too low.

The aileron on a plane's wing

But you'll also notice that the stabilizers aren't just in one piece. This is because sometimes you don't want to fly straight ahead. The smaller pieces are called control surfaces, and the pilot can move them to deflect more air, which then rotates the airplane. The one on the vertical stabilizer is called the rudder, and it turns the plane from side to side ("yaw"), while the ones on the horizontal stabilizer move the nose up and down ("pitch"). There's also a set called the ailerons out on the wingtips to control roll. Now, it's worth a brief digression into how these are used to maneuver the plane. The elevators are the most important of the three, as they control which way the nose is pointed, handy if you want to go up, go down, or change the amount of lift you're generating. That's important if you want to turn, a procedure that normally involves rolling the plane to the side and increasing generated lift, so that the extra lift pulls the plane's course to the side. If done right, this doesn't require using the rudder at all, and leaves everyone on the plane feeling like the outside world has tilted and things have gotten somewhat heavier. This is why when you fly and the plane banks, you don't feel like you're about to fall out of your seat. You basically never want the plane to be pointed very far from the direction it is flying in yaw, so the rudder is mostly there to keep that from happening if you have, say, an engine failure, or for the rare cases where it's necessary, like landing in a crosswind. The pilot also has a way to adjust the neutral position of these surfaces, known as "trim", because the appropriate position changes with every alteration in speed, power and altitude, and holding force on the controls gets tiring.

Flaps and slats deployed on landing, as shown in shadow

Now, for a lot of planes, there are other devices on the wing besides the ailerons. These are usually to help reconcile the two basic desires of a designer: when landing, you want a big wing producing lots of lift, but that produces a lot of drag, which is bad if you want to go high or fast or far. So you'll install flaps on the back of the wing and maybe slats on the front, which allow the pilot to change the size and shape of the wing during flight. They'll be extended for takeoff and landing, and retracted for minimum drag during cruise. These can range from quite simple to very elaborate, and most have multiple settings, allowing more lift with relatively little drag for takeoff, and a more sharply curved higher-drag setting for landing. There are also spoilers, which are there to reduce lift when that is desirable, such as when trying to descend quickly or just after landing, because brakes work better when there's weight on them. And some planes have air brakes, panels which deploy if you need more drag because you want to slow down fairly quickly.

Landing gear

The last thing worth noting is the landing gear. These are necessary because eventually the plane will run out of fuel, and it's better for everyone if there's a way to stop that doesn't require leaving bits all over the landscape. On most planes, these retract to reduce drag, but that's complex and can cause problems if the pilot forgets to put them down, so even today, simpler planes still have fixed landing gear. And occasionally you get a plane fitted with floats so it can land on water, or even skis for arctic operations, but these are rare and tend to hurt performance.

1 Yes, people who want to nitpick this statement, I am extremely well aware that this is not universally true, and I can also think of many counterexamples, but it suits my pedagogical purposes here. ⇑

2 The normal explanation for how a wing works is wrong. The shortest true version is that wings push down the air, which pushes the wing back up. Another version is that they are devices that produce high pressure on the bottom and low pressure on top, sucking the plane upward. How these things happen is too complicated to get into here. ⇑

Comments

OTOH if you neglect that you'll lose too many planes and pilots to be able to do any of the allegedly more important missions.

The interaction between the rudder and aileron seems underappreciated in most of the layman's understanding of what each does - skidding turns generally being frowned upon, the rudder is functionally a trim tab for forces primarily developed by the ailerons or engines, outside of the few circumstances when uncoordinated flight is desired. Kudos for bringing that distinction out!

Also, you missed out on the traditional jokes about how the four forces are not actually thrust, etc., but rather money, dreams, and regulations. ;)

What about the Coanda Effect? Isn't this the reason planes don't fall out of the sky?

The Fatherly One:

Does that matter for anything that isn't an An-72 or An-74?

No, the Coanda Effect has no relevance to a normal airplane. I didn't want to spend time on Kutta–Joukowski circulation and all the other stuff that you get into when you start looking closely at where lift comes from, because it's not relevant to the point of the post, and I don't remember that part of aerodynamics fondly.