By the end of 1942, Section T of the American National Defense Research Council had solved one of the great problems in anti-aircraft gunnery. They had created the proximity or VT fuze, which would go off when it sensed it was near a target instead of being set to go off at a specific time after it was fired. The formidable problems of building a mechanism that could survive being fired out of a gun had been solved, and reliability during tests was good enough that the first batch of 5,000 shells was ordered to the Pacific under the care of Deak Parsons, a naval ordnance officer who had been instrumental in the VT fuze project and would later become famous for arming Little Boy on the way to Hiroshima.1

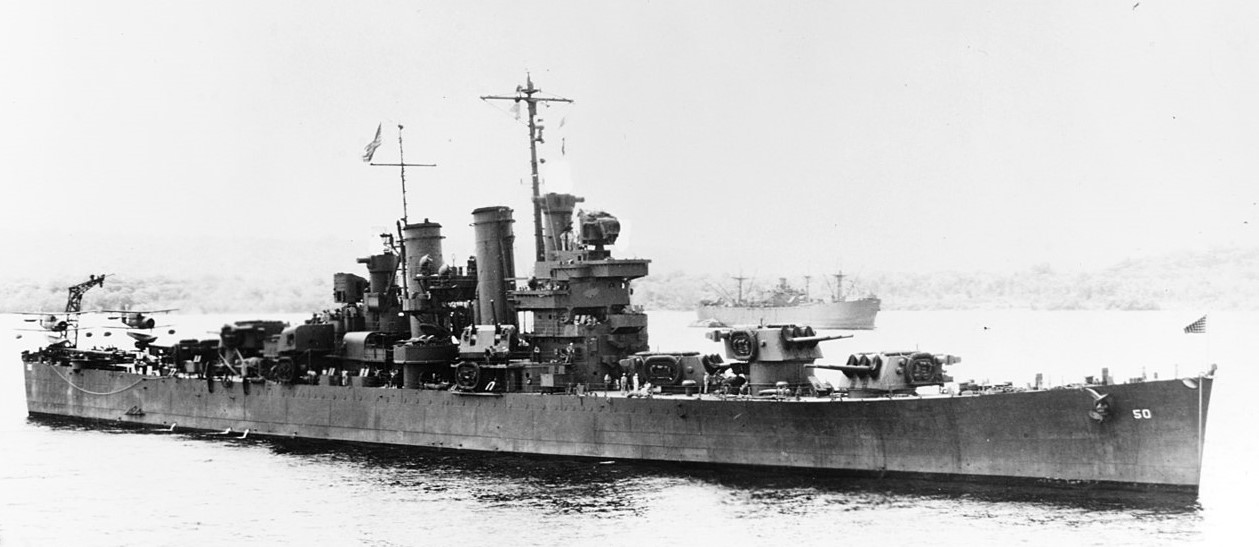

USS Helena in 1943

Parsons consulted Admiral Halsey, who informed him that the cruiser Helena and the carriers Enterprise and Saratoga were the most likely to come under air attack, and thus the fuzes were loaded aboard those vessels. Parsons himself joined Helena, and was present during the first combat use of VT fuzes on January 5th, 1943. Helena was part of a cruiser-destroyer group that came under air attack while returning from bombarding Munda on the island of New Georgia in the Solomons. The bombers arrived overhead before they could be spotted, but Helena's 5"/38 guns managed to down a retreating Val dive-bomber with their third salvo, an incredible performance. The surface ship had gained a major weapon against the aircraft.

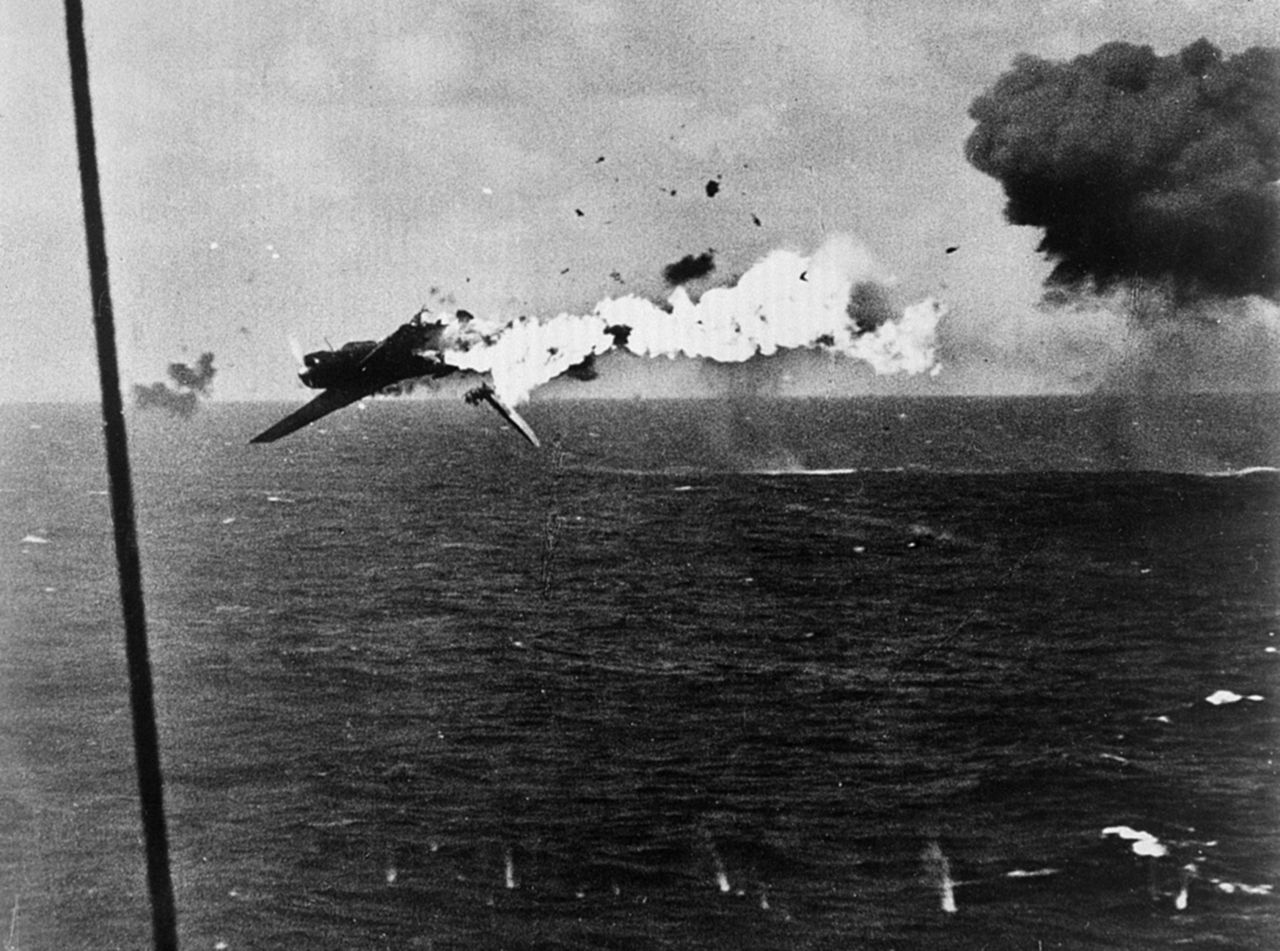

A B6N Jill shot down by a VT-fuzed 5" shell, 1943

The Pacific would remain the primary focus of VT fuze deployment for the rest of 1943, although they were also used by the USN and RN to defend the beachheads of Salerno and Anzio. Duds were still very common, and the possibility of a fuze falling into enemy hands and allowing either duplication or the development of countermeasures was seen as unacceptable. This risk would be greatly mitigated if the shells fell into the ocean, and Japan was also seen as the least likely of the three Axis powers to develop some form of countermeasures.2 Development of VT fuzes for the Army's artillery would continue, but they would not be released for service until it was judged too late in the war for any response to be made. During 1943, 9,128 rounds of 5" VT ammo were fired, knocking down 61 airplanes. The figure of 155 rounds per kill compared extremely favorably with the value of 508 for time-fuzed 5" shells during the same interval. During 1944, the number of VT fuzes used climbed to 32,826 as production spooled up. Despite improvements in the fuzes themselves, the number fired per kill also climbed to 421, primarily because of doctrine focusing on opening fire early, enabled by superior American logistics.

A Kamikaze attack off the Philippines in late 1944 is met with VT fuzed 5" shells

But the VT fuze really came into its own in 1945, when the kamikaze threat reached its peak, subjecting the Allied navies to some of the heaviest air attacks ever seen. Nearly two-thirds of the VT fuzes expended during the war were used in only seven and a half months, shooting down over 200 planes, and revealing another way in which the VT fuze had changed the AA picture. Previously, large guns had been restricted by their fire-control systems, which had to track the target in four dimensions. Such systems were large and expensive, which limited the number that could be carried, and also took time to settle in on the target. Short-range targets needed faster responses, and while simple angle-only directors like the Mk 51 worked quite well with light AA weapons, these often lacked lethality. VT fuzes could bridge the gap between the two, as they did not have to be set before launch, and the last year of the war saw many ships hooking up light directors like the Mk 51 to their 5" guns, multiplying the number of threats they could engage and slashing response time.

A V-1 dives into London

During 1944, most of the emphasis in fuze development moved to meeting the Army's requirements. Heavy AA guns also provided high-altitude air defense to ground troops, and could likewise benefit from the use of VT fuzes. Employment near the front line was limited by the danger of duds falling into enemy hands, but the second half of 1944 gave the VT fuze an opportunity to shine in Europe. A week after the Allied landings in Normandy, the Germans launched an assault on London with a new weapon, the V-1 cruise missile. Flying low and fast, they were extremely difficult targets for both fighters and conventional AA guns, but the arrival of the VT fuze, along with improved fire-control radars and computers, brought the percentage of V-1s killed by the coastal belt of AA guns from 17% in June to 74% in late August. Later, as the Germans were pushed out of range of southeastern England, they turned the V-1s on the port of Antwerp, critical to supplying the Allied armies now on Germany's frontiers. VT fuzes were again critical to blunting the V-1 threat, although their most famous role in the European Theater was yet to come.

Artillerymen prepare shells in the closing months of the War in Europe3

By late 1944, it was obvious that the war was drawing to a close, and the plan had been to release the VT fuze for general service on Christmas Day. The German offensive in the Ardennes began 9 days before the appointed date, and the AA fuzes were released for immediate use, followed two days later by the airburst artillery fuzes. The team from Section T had done excellent work in preparing the groundwork for the use of the fuzes, and American artillery immediately set to work with deadly effect, raining down the new shells upon the heads of the attacking Germans. The VT fuze, setting off the shells just above the ground, produced a spray of shrapnel from above that bypassed traditional cover. Traditionally, this had been done with time fuzes, although much as with AA fire, the VT fuze was much more reliable and precise. Contrary to many claims, most famously George Patton's statement that "The funny fuze won the Battle of the Bulge for us. I think that when all armies get this shell we will have to devise some new method of warfare" the Army's official history of the battle states that only limited use of the fuze was made before January, mostly in cases where limited visibility would have kept timed fire missions from working properly. The most likely reason for this was the logistical constraints of the battle, and while proximity-fuzed airbursts remain an effective weapon today, they have not revolutionized warfare as Patton predicted.

A kamikaze splashes near Enterprise off Okinawa

Postwar analysis indicated that a 5" VT shell was about three times as effective as a conventional time-fuzed shell in AA fire.4 And for all that some have overstated the benefits of the VT fuze, this might well have provided the margin required to defeat the intense kamikaze attacks the fleet faced off Okinawa. For that reason, and as a marvelous example of ingenuity and raw productive power, the "deadly fuze" deserves to be remembered.

1 Three scientists were given naval commissions and dispatched along with Parsons, most notably James Van Allen. ⇑

2 Ultimately, no countermeasures were developed, primarily because the Axis couldn't figure out which of several possible techniques the VT fuze actually used. ⇑

3 The difficulty of finding pictures of Army artillery in Europe has eclipsed my traditional difficulty with illustrating Falklands posts. I cannot find a single image on any government site of American towed artillery in action during the last ~6 months of the war in Europe. ⇑

Comments

Very interesting series, but I'm confused by the timed fuzes. How exactly were they set? 15-20 rounds per minute (and a moving target) means there must be some fast way, but I have no idea what it would be.

The fuze was usually set by turning a ring on the nose of the shell. In WWII, this was done by a machine that got information from the fire-control system and set the ring as appropriate. The US integrated the fuze-setter into the hoists on the 5"/38, but most British guns had it as a separate step, which cost about 25% in rate of fire. I go into more detail here.

I see my comment on the previous post was overcome by events : )

The use of "fixed time" fuzes dates back to at least the invention of the Shrapnel Shell. (1780s, named after its inventor, Henry Shrapnel. Really.) The "timed" fuze probably predates that, but I'm too lazy to dig up more info right now. Early timed fuzes used adjustable-length powder trains, which were rather unreliable. They were replaced by clockwork in the early 20th century.

The paucity of images of US towed artillery in the late-war is rather odd, given how much of it we deployed. Was there perhaps a directive to avoid photographing artillery for OPSEC reasons?

I wasn't finding a whole lot of photos in general of the later part of the European war. I'd guess that most of what exists just isn't available on the web, and artillery has never been the glamour arm.

Anyone who thinks artillery is unglamorous needs to look up the term "Yoke Target".

...I'm almost wondering if - given the time period we're talking about - everybody was too busy shooting and moving to get any decent pics.

@Mike That doesn't sound right. There should have been plenty of civilian reporters around as correspondents, even if all the Army's own photographers had been handed rifles and pressed into the front line.

The RN apparently shot down ~11 V-1s. I don't know whether this number includes any shore forts, but at least some seem to have been by ships at sea.

(Posted here because the article covers V-1 defence; I don't know whether the 1944 RN actually had VT ammunition. I also don't know whether these were ships specifically assigned to V-1 defence (which did exist), or ships that randomly encountered a V-1 while doing something else.)

That (plus one) possibly means the RN has shot down more missiles in actual combat than any other navy (I know of ~5 by the USN) but none of the ones actually aimed at it (this was after V-1s stopped being aimed at Portsmouth/Southampton, and they probably didn't hit any of the 7 Falklands Exocets).

@Alsadius Anyone who thinks artillery is unglamorous needs to look up the term “Yoke Target”.

Today I found out there is a brand of women's underwear called "Yoke" that is sold at Target department stores.

Don't worry, I worked it out. Turned out to be the same as the WWI concept of a "zone call" that I encountered as an 8-year-old reading Biggles.