While the heavy AA guns and their dual-purpose successors could be potent weapons against aircraft in the right situation, there were also cases where their limits were sharply revealed. Even the fastest-firing of them was limited to no more than one round every three seconds or so, and when the target was a strafing fighter or a torpedo bomber closing in for the drop, they simply could not respond fast enough. Smaller weapons, of limited range but capable of filling the air with steel, were needed.

Octuple Pom-Pom on HMS Rodney

Initially, these were simply versions of the standard machine guns used ashore, fitted with ring sights and bolted to a convenient railing. These were adequate in World War I, but shortly after the end of the war, the British saw the need for something better. They had also made use of the 2-pdr Pom-Pom,1 a 40mm autocannon, for AA firepower and decided to base their future light AA weapon on it. Development began in 1920, but lack of funding slowed development, and the famous octuple 2-pdr Pom-Pom didn't enter service for another decade.2 It was a revolutionary weapon, introducing director control3 and power operation to automatic AA weapons. The 2-pound shell was powerful enough for aircraft of the era, with a 0.16 lb bursting charge. On the downside, rate of fire was only 90 rds/min/gun, and the choice to use existing ammunition limited muzzle velocity to only 1,900 ft/sec. By the late 30s, this was clearly insufficient, and an improved version capable of about 2,300 ft/sec was designed. It was not capable of firing the old ammo, and for some bizarre reason, both low and high-velocity weapons were kept in production throughout the war.

Unrotated Projectile launchers atop the turrets of HMS Nelson

Unfortunately, the 2-pdr was clearly on its last legs by the beginning of the war. Even the high-velocity version was obsolescent by the end of hostilities, and the small shell was also not very effective against the much more durable aircraft that were filling the skies. But they sprouted from British battleships in great numbers. The WWI-era battleships had 2-4 octuple mounts each, while the King George V class ships were commissioned with four mounts, and ended the war with as many as eight octuples and six quads. Many of these ships also carried what was known as the Unrotated Projectile, a cover name for a rocket that would deploy a cable with an explosive charge attached. The idea was to entangle the attacking aircraft and destroy it, but in practice these "aerial mines" proved easy to avoid and the mounts were replaced by late 1941 with more conventional AA weapons.

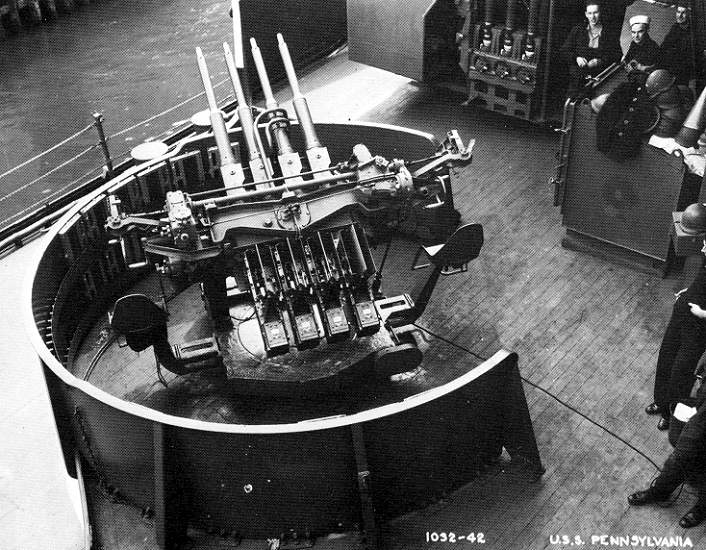

1.1" quad mount aboard Pennsylvania.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the USN was somewhat slower to respond to the threat. It relied solely on machine guns until the late 20s, when development began on a 1.1" weapon firing a shell of about 1 lb. These weapons, in quad mounts, were entering the fleet at the start of the war, with the treaty battleships designed to carry four of them. One unusual feature of this mount was that the barrels pivoted side-to-side to allow them to track dive bombers at high angles, when a small change in angle might require a large change in train. However, the mount was unreliable in service and the lightweight shell was grossly insufficient for the task at hand. Something better would be needed, and it came, oddly enough, from neutral Sweden.

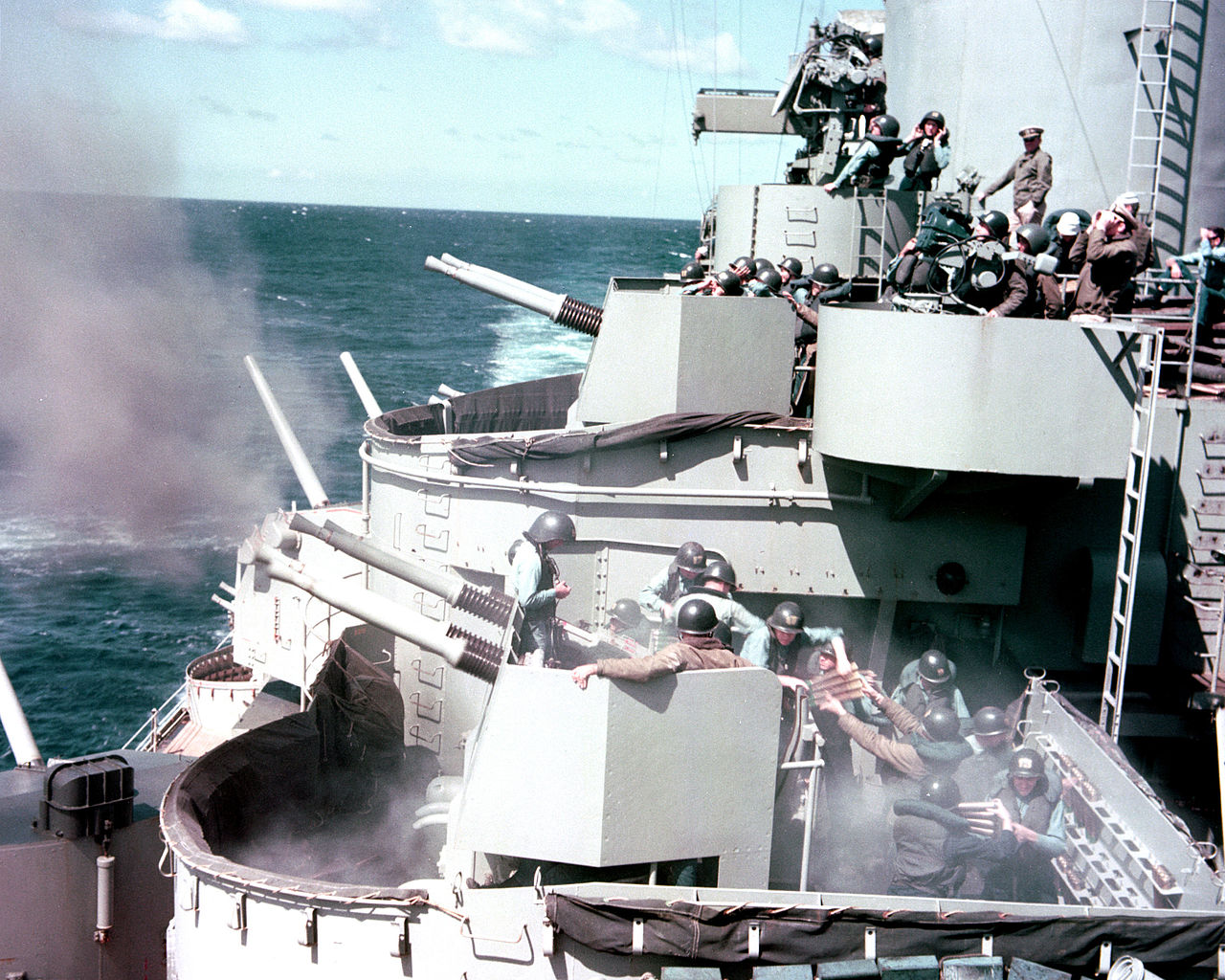

40mm guns in action aboard New Jersey. Note the 4-round clips being passed to the guns.

The 40mm Bofors was undoubtedly the most successful automatic AA gun of the war, used by every major naval power in one form or another. It fired a 2-lb shell at about 2,800 ft/sec, and could maintain a sustained rate of 90 rpm per barrel thanks to the use of four-round clips which were loaded as the gun fired.4 The original design was complex and difficult to build,5 but the US redesigned the weapon for proper mass production, and Chrysler and its subcontractors built 60,000 guns over the course of the war, at half the projected unit cost. Many of these weapons found their way aboard ships, in single, twin, and quad mounts. These, like the 2-pdr, were power-operated and driven by directors, and they took a ferocious toll on Axis aircraft. In the Pacific, the Bofors was responsible for a full third of Japanese aircraft shot down by American AA gunfire, more than any other weapon. The British also made use of the Bofors, although it served alongside the 2-pdr throughout the war. After the war, both navies kept it in service, and a few weapons remain in use to this day.

Quad 40mm Bofors mount onboard Massachusetts

But even these weapons had their drawbacks. They were large and heavy, the quad 40 weighing as much as a single 5"/38, and were not quite adequate at very close range. A particular problem was that they, like most naval guns, had separate pointers and trainers, which reduced their ability to respond to targets close in. Initially, the Americans and British both used .50 cal machine guns, but these were seen as inadequate for the task even before war broke out. Weirdly, the solution to this problem came from another neutral country, Switzerland.6

20mm Oerlikon aboard Iowa

The 20mm Oerlikon was usually mounted as a free-swinging weapon, controlled by a single gunner looking through a ring sight.7 While the bullets weighed only an eighth of what those of the Bofors did, it could empty its 60-round drum magazine in only 8 seconds, and needed only to be bolted to the deck to be used. The ability to keep fighting after damage that took out the ship's power was a major advantage, as shown most graphically when Repulse and Prince of Wales were sunk. The 20mm was very effective early in the war, getting almost half of AA kills on Japanese aircraft in the second half of 1942.8 Against the Kamikazes, however, it was reported that the main value of the 20mm battery was to warn the rest of the crew that a plane was about to hit.

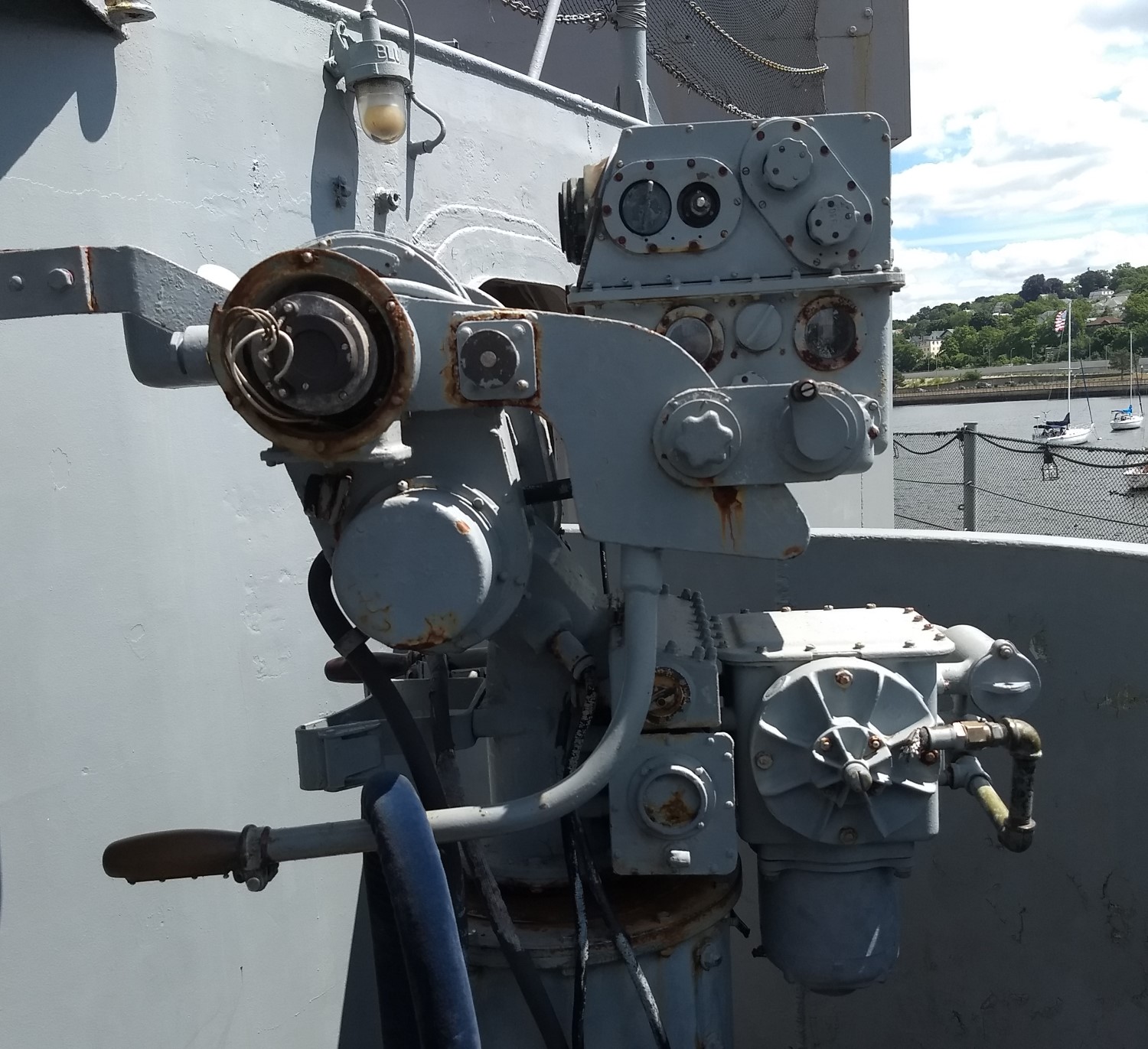

20mm Oerlikon aboard Cassin Young, with Mk 14 sight9

So did America contribute nothing to the field of light AA beyond mass production? Certainly not. At the beginning of the war, the typical light AA weapon was aimed by use of a ring sight, a simple device which gave the gunner some idea where to start with his aiming. Tracers would then hopefully let him walk his fire onto the target. A team at MIT under Charles Stark Draper was charged with developing something better.10 The result was the Mk 14 gunsight. This device used a pair of gyros to measure the rate of rotation of the sight as the gunner tracked the target. This rate was used to displace mirrors which gave the correct lead for the target, at least at close range.11 A second man was used to set the range on the sight. In addition to being mounted directly on the 20mm Oerlikon, the Mk 14 was fitted to a "dummy gun" and became the Mk 51 director, which was widely used for 1.1" and 40mm guns, and even linked to the 5" guns towards the end of the war, to attack surprise targets the Mk 37 couldn't track effectively.12

German 3.7cm SK C/30 in twin stabilized mount

Both Axis powers made at least some use of the Bofors, but in neither was it the mainstay of their air defenses. The Japanese used a triple 25mm that was inferior to the 40mm in range, lethality, and rate of fire. For some reason, they considered it an excellent weapon.13 The Germans had a 37mm gun with reasonable performance, apart from one major flaw. It predated the end of the Treaty of Versailles, when Germany was not allowed heavy automatic weapons, and was thus semi-automatic and could only fire about 30 rpm. The Germans thus relied more on their own 20mm design, but it suffered the same drawbacks as the Oerlikon.

Mk 51 director aboard Massachusetts

The war saw dramatic increases not only in the capability of light AA weapons, but also in their number. Iowa, originally designed with only four quad 1.1" and a few .50 cal machine guns, was completed with 15 quad 40s, a count which grew to 19 before she sailed for the Pacific,14 and 52 single and 8 twin Oerlikons. In this, American ships, larger and with greater reserves of stability, had a major advantage over their British counterparts. That said, it was not uncommon for destroyers to lose main guns and torpedo tubes to provide space and weight for light weapons. Even aboard the battleships, the addition of the guns was not without problems. Their crews crowded the ships with almost 50% more men than they were originally designed for, and weapons had to be placed in locations that complicated ammunition supply, suffered damage in rough seas, or were completely untenable due to muzzle blast if the main guns were in action. More guns were placed amidships, replacing the boats that had formerly occupied the space. But by 1945, the American battleships were some of the most formidable anti-air platforms afloat, although the extra mounts disappeared quickly after the war, to save on manpower and the cost of keeping them operational.

While light AA weapons were always something of an afterthought to the designers of battleships, they were vital to their performance during WWII. Ultimately, the entire category was rendered obsolete by better aircraft and the first guided weapons, but for a few years, they achieved a prominence equivalent to the other batteries.

1 So called from the noise of its firing ⇑

2 There were also quad mounts, used mostly on smaller ships. ⇑

3 The major advantage of early director control was that it moved the aimer away from the smoke and noise of the gun's firing. Most of them were barely more sophisticated than the ring sights used previously. ⇑

4 The Pom-Pom couldn't sustain its full rate of fire for long periods due to the difficulty of reloading. It used 140-round belts stored in boxes next to each gun, and once these belts were exhausted, the gun had to cease firing to reload. ⇑

5 One US engineer is reported to have said that it was designed to single-handedly solve the unemployment problems of the Great Depression. ⇑

6 To make this even more amusing, both weapons had roots in the period after WWI, when German arms firms moved most of their operations to other countries to evade the Treaty of Versailles. ⇑

7 As a follow-on to the previous footnote: At one point, Oerlikon was nearly bankrupt after the USN rejected an early 20mm gun. Only a Japanese purchase of the design allowed them to continue development, and ultimately led to the weapon used so successfully against Japan. ⇑

8 For the war as a whole, they made about 28% of kills. ⇑

9 Photo courtesy of The Fatherly One. All other non-archive photos in this section from my collection. ⇑

10 Draper would later develop the guidance system for Polaris. ⇑

11 I intend to give this amazing piece of technology a careful examination at some point. ⇑

12 This worked mostly because of proximity-fuzed ammunition, as the Mk 51 obviously had no way to set time fuzes. ⇑

13 The Japanese did light AA very strangely. Instead of fitting directors, they had the officer in charge point at the target with his sword. ⇑

14 The other three ships of the class carried 20, but putting one atop Turret 2 would have blocked vision from the flag level of the conning tower, so three Oerlikons were placed there instead. ⇑

Comments

What is "director control"? I get the impression from the text that it is some sort of complicated gunsight.

It's essentially the same as the directors used for the main and secondary batteries. Information about target position is transmitted from a remote location to the weapon, and used to provide orders on where to point the gun, either directly or via following the pointers.

Filling the air with what now?

On that subject, the 20mm Oerlikon did fire HE/HEI shells with a whole eleven grams of explosive fill; these were common in US and UK service by 1943 at the latest. Substantially more effective than solid shot against aircraft, particularly lightly-built Japanese aircraft.

Also somewhat more dangerous to the user, as a 20mm fuze couldn't incorporate all the safety interlocks of a larger shell. If you fired 20mm HE with the muzzle cover still on the gun, you wound up with a snubnose Oerlikon and probably some very annoyed shipmates in the adjacent mounts.

That statement was meant to be idiomatic, not literal.

How did I get that wrong? I'm looking now, and there doesn't seem to have been much non-HE ammo in use.

I did not know that. Thanks.

"90 rpm per barrel thanks to the use of four-round clips which were loaded as the gun fired"

Does this mean that the men were loading 22 clips per minute by hand? Per barrel.

Yes. The rounds essentially came in stripper clips, and would be pushed into the curved feed section at the top of the gun. See this picture for a fairly clear view of them.

Potentially relevant meme

Sorry for the necro, but I finally happen to have a meaningful comment to add and it's too good of an occasion to pass on.

To expand on what John was saying on the accidental 20mm snubnose field modification, the Navy actually tought this through. The first 2 rounds in a drum were actually solid shots, so that if you had no time to (due to the odd surprise kamikaze) or simply couldn't (due to it being frozen to the barrel) remove the muzzle cover, these two rounds would shoot through it and clear the barrel mouth enough for the following shells to go and do their business without explode-in-your-own-face secondary effects.

That's very interesting, and makes a lot of sense. Thanks.

And I have no problem with necros. I'm trying to create a reference, and new information is always welcome, no matter how long ago I wrote the original.

Do you know how shells from AA guns were fused? Were they simple impact fuses or did they have a way of having the shells go off at a particular altitude, so they could potentially hit planes with shrapnel, even if they didn't score a direct hit?

They were simply impact-fuzed, although the 40mm also had a self-destruct time fuze to reduce the risk of it coming down on the heads of friendly units. This was also thought to make it significantly more effective at dissuading attacking aircraft, which was a major part of the job of light AA guns. This was pre-set at the factory, but there simply wasn't room for anything more sophisticated. It's only very recently that there was room in a small shell to fit sophisticated fuzes.

How was light-AA ammunition stored and moved to the guns? In that 40mm New Jersey shot it looks almost like they just have a chain of men passing ammo from inside!

That was pretty much it. A mechanism for taking stuff from a fixed position and moving it to a rotating, elevating gun is annoying now, and would have been much worse back then. A couple of guys to pass clips is a lot easier, and manpower was cheap back then. (This was true for basically anything that people could carry, which caused some trouble in the 80s.)