Previously, we discussed the how the State Department’s shrewd overseas maneuvering successfully stymied Southern hopes for procuring a European ironclad fleet, while Confederate agents had more success building commerce raiders in England, shielded by paper-thin legal technicalities and tacit English consent. The first English-built commerce raider, the Florida, had failed to damage much on its initial cruise beyond Northern egos, but that was set to change.

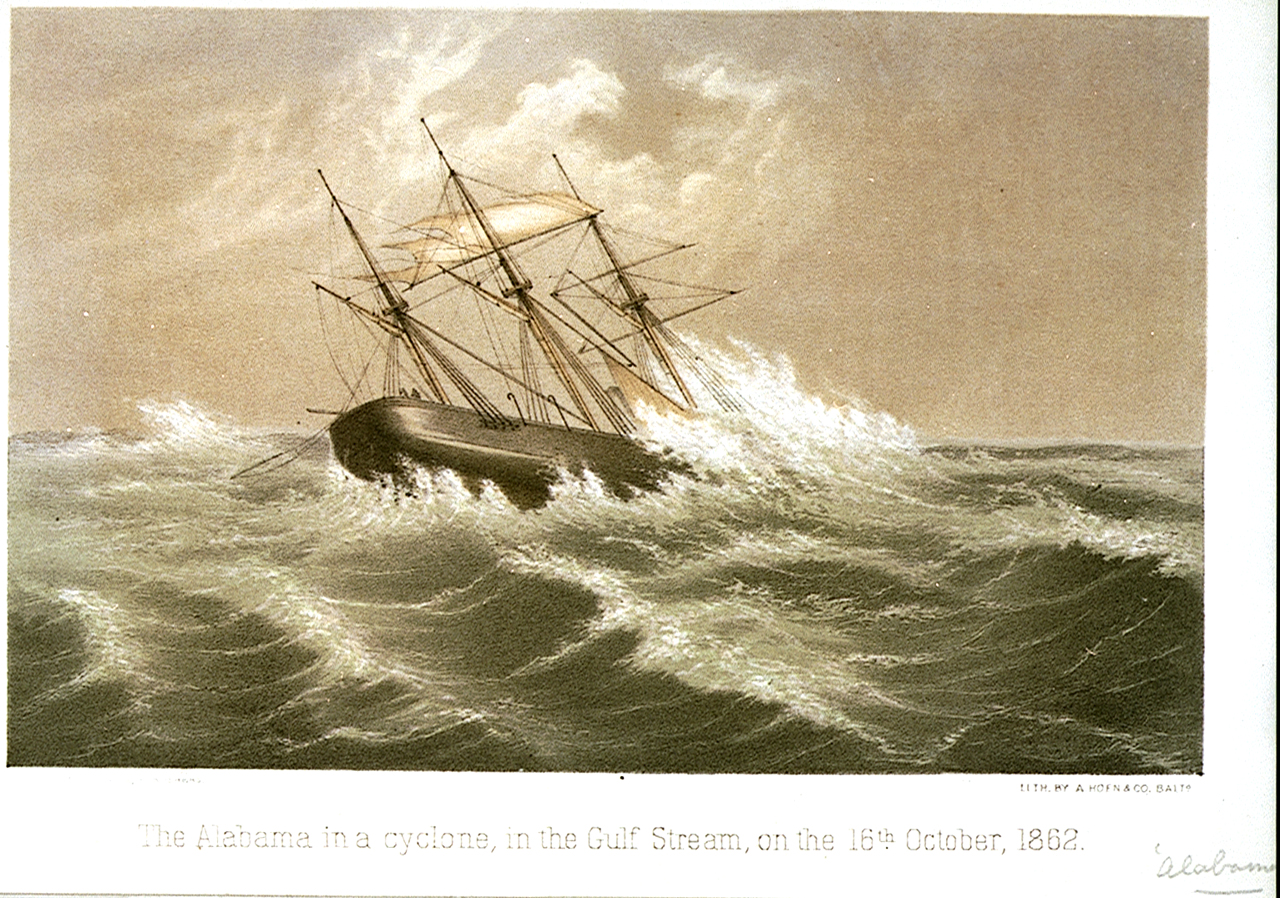

CSS Alabama at sea

In 1862, the most famous of the Confederate raiders, the Alabama, set sail. Like the Florida, she has been constructed in England. In this case, however, Charles Francis Adams was actually able to gather enough proof of the ship’s wartime purpose to compel English authorities to move to detain the vessel. Acting with admirable decisiveness, Bulloch took her out for a “trial run” and escaped detention, thus saving her for a remarkable career afloat.

The Alabama was commanded by Raphael Semmes, the former captain of the Sumter, who later expressed great satisfaction with his new command, calling her “a very perfect ship of her class.” She could operate both under steam and sail, and when not under steam, her propeller could be removed from the water so as not to create additional drag. Capable of speeds in excess of thirteen knots and armed with eight cannons, she possessed “the lightness and grace of a swan” and a commander well-suited to her strengths.

The Alabama started her career making a truly impressive haul of twenty whalers and cargo ships in the fall of 1862. From one of these ships Semmes captured “contraband” in the form of David White, a black slave whose master was from Delaware. According to Semmes, White was paid as a crewmember, and throughout the war refused several offers of freedom despite being “tampered with by sundry Yankee consuls” in ports the Alabama visited.1

By October of 1862, in Semmes’ account, the pickings in the Northern Atlantic were beginning to get rather scarce. “Such of the Federal ships as could not obtain employment from the Government as transports, or be sold under neutral flags, were beginning to rot at the wharves of the once thrifty seaports of the Great Republic.” Semmes turned south and near Cuba captured the Ariel, a steamship carrying more than $10,000 in silver coin and U.S. notes—prompting the Union navy to provide future steamers on the California – Panama – New York circuit with armed escorts. Semmes then cruised west, into the federal sea bombardment of Galveston and his first fight.

By his own account, Semmes departed from his usual habit of commerce-raiding intentionally, thanks to capturing a newspaper in which “[t]he Northern press, in accordance with its usual habit, of blabbering everything” had detailed the route of a Union naval flotilla destined to invade Texas. Somewhat audaciously, Semmes intended “to surprise this fleet by a night attack, and if possible destroy it, or at least greatly cripple it,” trusting to surprise – having “learned from the enemy’s own paper that the Alabama was well on her way to the coast of Brazil and the West Indies,” – and laziness on the part of his enemy to help the Alabama avoid Union gunboats.

Upon his arrival off of Galveston in the waning hours of January 11, 1863, however, Semmes was surprised to find that city (which had previously been occupied by Northern troops) under bombardment by Union gunboats. While Semmes was pondering his next action, the USS Hatteras steamed forth to investigate the Alabama, which allowed the Union vessel to close to about one hundred yards.

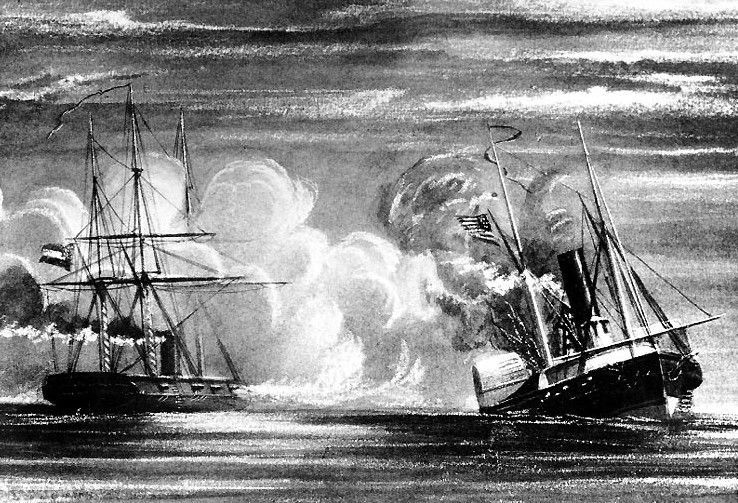

USS Hatteras sinking

The Alabama identified herself as an English vessel, and then, as the Hatteras let down its boat to investigate, declared itself to be “the Confederate States steamer Alabama!” and gave the Hatteras a broadside. The Hatteras returned in kind, and (according to her captain – Semmes said he “saw no evidence” of this) attempted to close with the Alabama in order to board her, but the nimbler Alabama evaded the attempt.

At this close range, both ships exchanged small-arms fire as well as cannon fire before a pair of Confederate shells set the Hatteras aflame and another disabled her engine. Unable to maneuver, the Hatteras continued to fire until the Alabama’s fire punched several holes below her waterline, at which point the ship surrendered. The Alabama suffered only one man wounded and minor damage; the Hatteras, five wounded and two killed. Evading pursuing Union gunboats, Semmes slipped into the night and charted a course towards Central America.

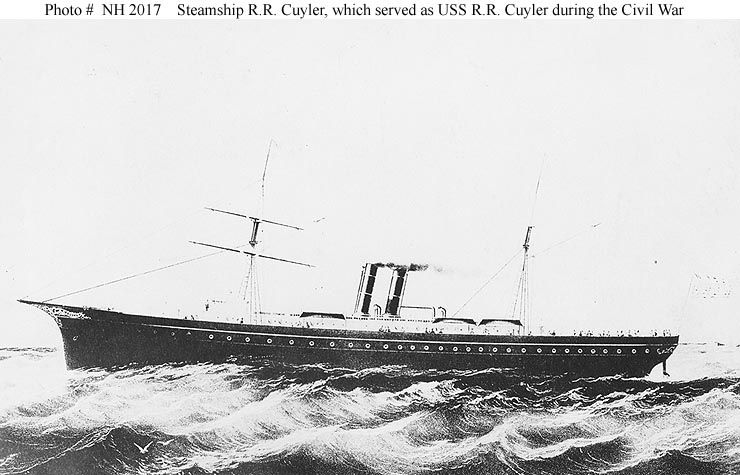

R.R. Cuyler

As if the Alabama was not causing enough trouble for the Union blockade, the Florida slipped out of Mobile in the early weeks of 1863, thanks in part to the cooperative crew of the USS R.R. Cuyler, who waited to pursue her until they could awaken their captain and receive his orders. We’ll discuss the Florida’s career, the deployment of further Confederate raiders, and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles’ response in our next installment.

1 Tragically, White did not survive the war, and to the best of my knowledge, we do not have any independent insight into his perspective of his time on the ship. ⇑

Comments

Why is this now titled 'Confederate Raiding' instead of 'Southern Raiding'?

It isn't. I certainly didn't forget what the series was called when putting this post up.

So the Hatteras sank after striking, according to the caption?

Non-ironclad early steamship battles are criminally underappreciated. These designs are amazing.

prompting the Union navy to provide future steamers on the California – Panama – New York circuit with armed escorts

So the steamers were going around the Horn? The panama canal wasn't built yet according to what I can find.

There were two major pre-canal shipping routes between the East and West coasts of the US. The obvious one went on sea the whole way, using the Straits of Magellan or the Drake Passage. The other involved three legs: a sea voyage to Panama, an overland trip across the isthmus, and then onto another ship to go the rest of the way. From 1855 onward, there was a railroad across the isthmus (closely paralleling the eventual canal route) to facilitate the overland leg of the itinerary.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PacificMailSteamship_Company specifically mentions the Confederate attempts to disrupt the commerce on the western side of a route that portaged across Panama. Probably not practical for bulky goods, but for high-value cargo?