In the late 40s and early 50s, the USN and RN struggled to deal with a new underwater threat. Previous ASW techniques, worked out to deal with the slow, battery-limited submarines of WWII, were inadequate in the face of underwater-optimized vessels like the German Type XXI and its expected Soviet descendants. Initially, these were based around better versions of the systems developed during WWII, with longer-range sonars and Limbo and Weapon Alpha replacing Hedgehog and Squid.

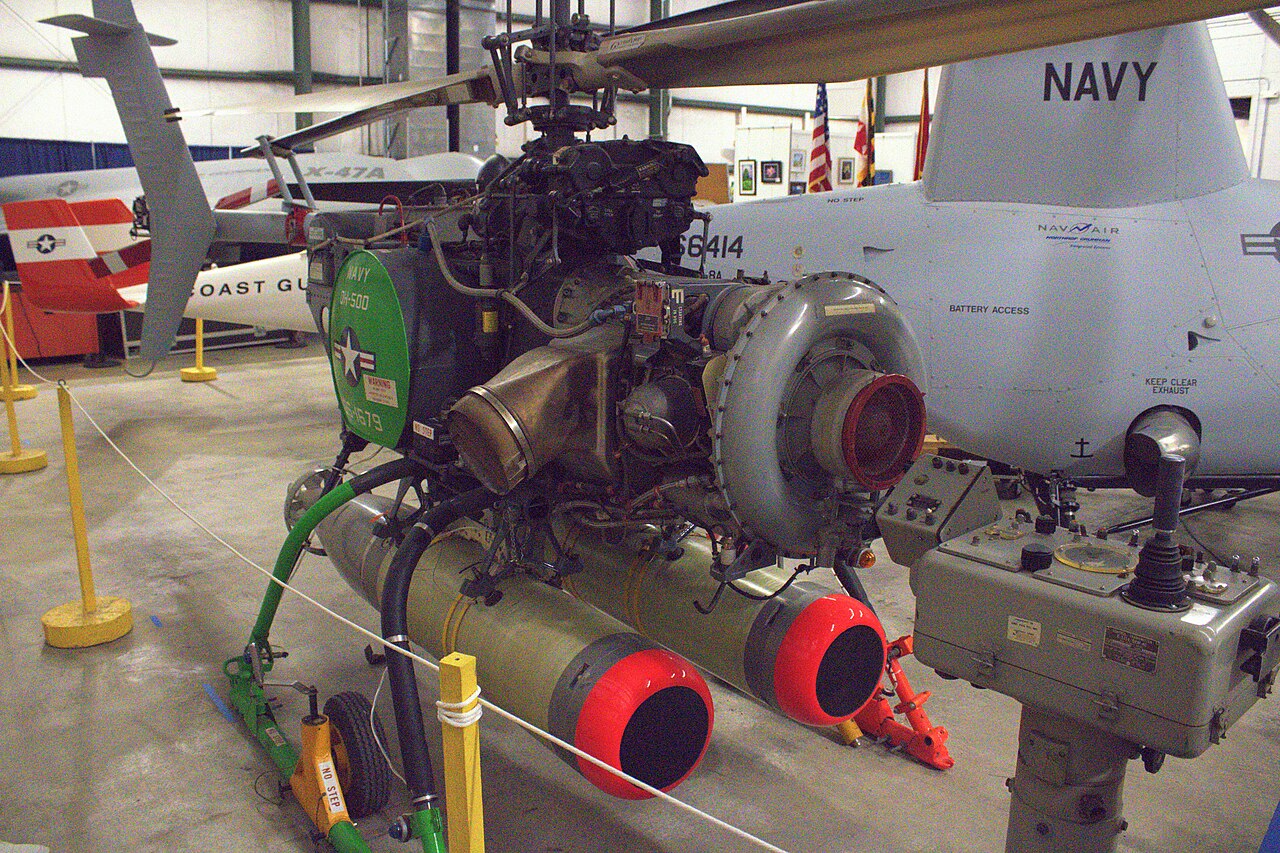

A DASH drone at Pima

But by the mid-50s, sonar ranges were getting close to 10,000 yards, way too far for those kind of depth-charge launchers to be effective. The submarine was moving, maybe unpredictably, and even if it was stationary, the sonar beams were wide and didn't give a precise enough location at range. Obviously, the homing torpedo was going to be at least part of the solution. First developed during WWII, it could handle quite a bit of uncertainty in the submarine's position by listening for the submarine and then homing in to blow it up. Initially, navies expected that the main long-range weapon would be heavyweight homing torpedoes, launched from the ship and wire-guided out to the point where their seekers could pick up the submarine. But it didn't work out that way. The big problem was simply that torpedoes were too slow for this to work well. A 40-kt torpedo, extremely fast for the time, would still take 7.5 minutes to reach a submarine 10,000 yards away, and the submarine could move significantly during that run. The obvious alternative was to deploy a smaller torpedo, probably one originally designed to be dropped by aircraft, through the air right on top of the submarine.

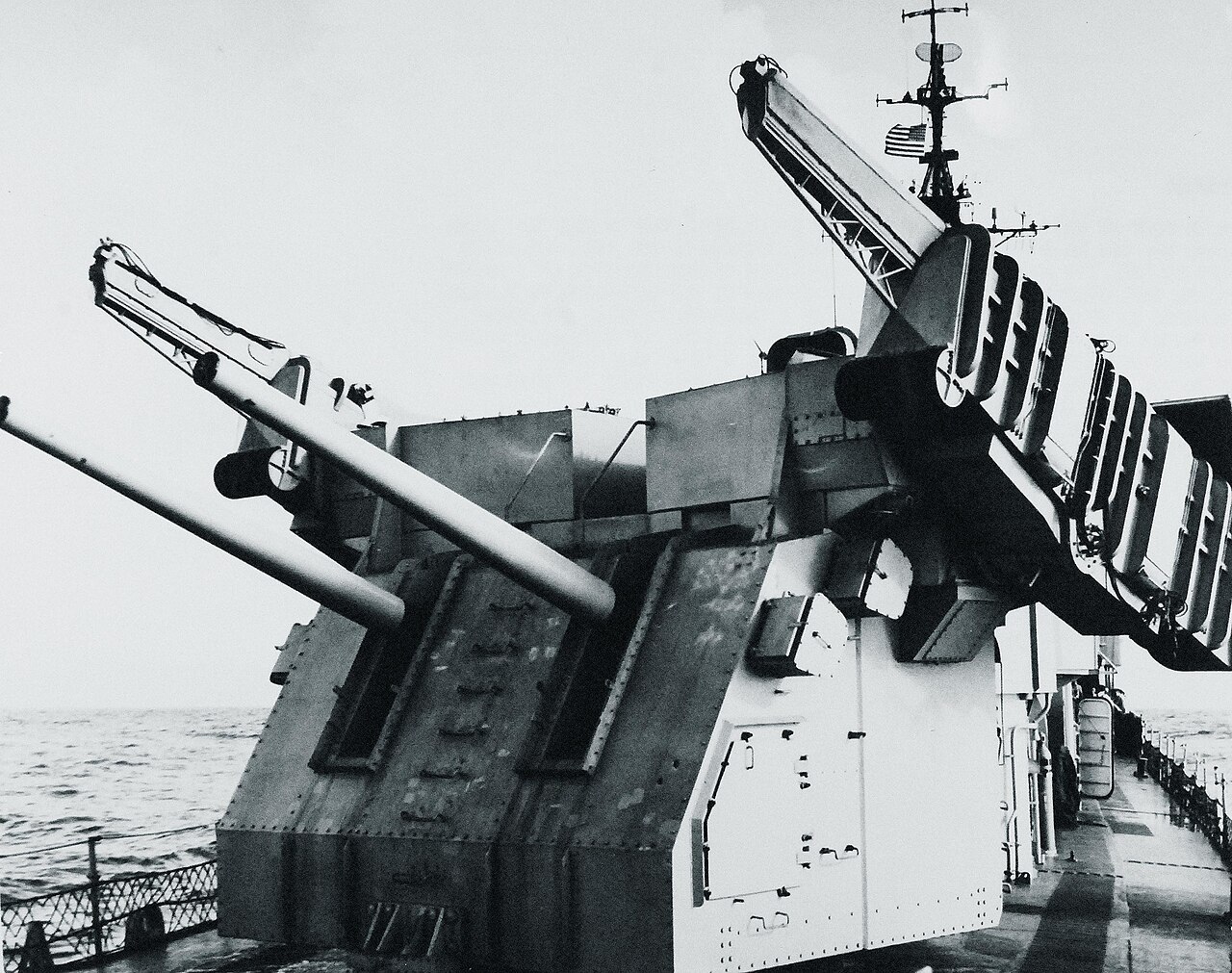

A RAT launcher on De Haven

And the obvious way to get it there was via some sort of rocket or something, which also raised the possibility of carrying a nuclear depth charge. The US did indeed go down this route, first with RAT (Rocket-Assisted Torpedo) and then with ASROC, but there were some problems. Both used unguided rockets, which meant that the torpedo might not land close enough to the submarine, and the ASROC installation itself was fairly big and expensive. That in turn raised questions about the ability to refit it to many of the older destroyers that were going to be the backbone of the ASW force well into the 70s. The solution they found to this problem would be in many ways years ahead of its time, but also an odd cul-de-sac in the development of military technology: the Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter, better known as DASH.

A Gyrodyne Rotocycle

DASH, more formally the QH-50, was based on the Gyrodyne Rotorcyle, about the smallest thing that can actually be called a helicopter instead of just an elaborate way to kill yourself. In particular, the coaxial rotors gave it a small footprint, making it easy to land on the sort of flight deck that could easily be fitted to the Sumner and Gearing class destroyers, while getting rid of the pilot would give it the payload to carry a torpedo or two, or maybe a nuclear depth bomb. It wasn't the most sophisticated helicopter in the world, or the safest, but that was considered acceptable. As an alternative to ASROC, it could deliver its weapon more accurately, and if the mean time between crashes was even a couple dozen hours, then in wartime, it would also be cheaper per weapon delivered.

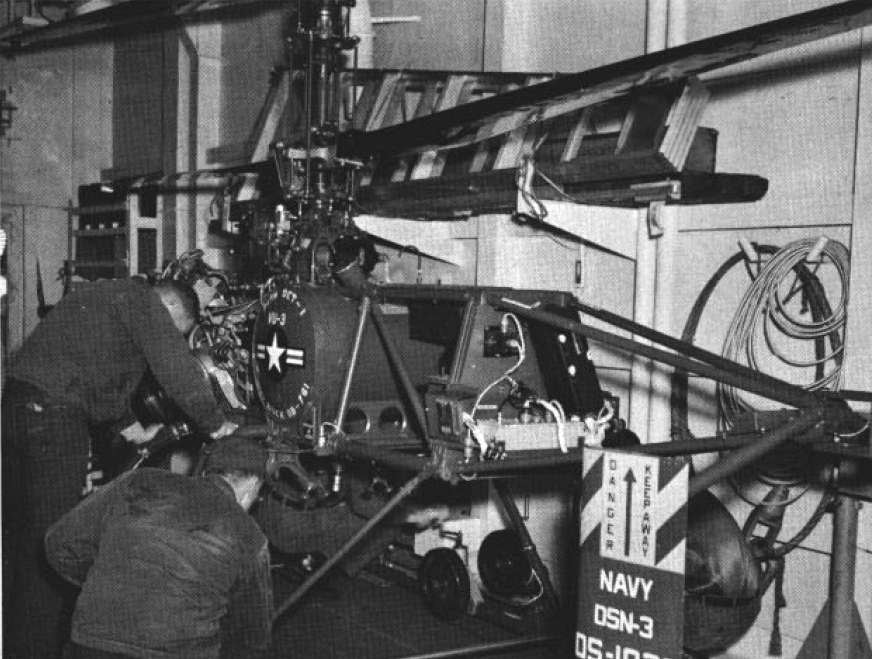

A DSN-1 landing on Hazelwood with a pilot aboard for safety

The initial contract was placed with Gyrodone in April 1958, and required that the drone be capable of being placed within 200 yards of a target at 10,000 yards, which would hopefully be close enough for the Mk 43 torpedo it carried to be able to pick it up. The first version, designated DSN-1,1 entered tests in 1960, but could barely lift a single Mk 43. To increase lifting capacity, the piston engine used on the DSN-1 was replaced by a Boeing T50 turboshaft engine. This also allowed the volatile and dangerous avgas to be ditched in favor of jet fuel, which was much more difficult to ignite. The initial operational version, the QH-50C, joined the fleet in 1963, the world's first armed unmanned aerial vehicle.

USS Radford with a DASH on her flight deck

It arrived into a fleet that had spent the last several years refitting destroyers, mostly WWII-era Sumners and Gearings, to carry it. To push off the cost of replacing the massive fleet of wartime destroyers, the USN had instituted the Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization Program, or FRAM. One part of FRAM was the addition of a small flight deck and hangar for DASH aft, where the ships had originally carried torpedoes and 40 mm AA guns, along with a torpedo workshop, maintenance facilities for the drone itself, firefighting equipment in case of a crash and 2,500 gallons of aviation fuel storage.

DASH and its operator aboard USS Nicholas

Operation was, at least in theory, relatively simple. The drone would be moved out of the hangar and made ready on the deck, where a local controller would order the takeoff. Controls were relatively simple, two knobs to set heading and altitude, and a stick to control the direction of movement. Once the drone was safely airborne, control would be passed to an operator in the CIC, whose scope combined the picture from the ship's sonar and local air-search radar. Once the submarine was over the target, the payload (two Mk 44s or one Mk 46 for the QH-50C, two Mk 46s for the more powerful QH-50D, or a W44 nuclear depth bomb for either type) would be dropped, and the operator in the CIC would bring the drone back. Once it was close enough to the ship, the deck operator would take control back and steer it in for a landing. In calm seas, this involved simply placing it over the deck and reducing altitude until the skids reached the deck, at which point a switch in the skid would automatically change the rotor pitch to keep the drone there. For rougher weather, the drone was equipped to lower a line to the deck, which could be secured and used to guide it in.

DASH undergoing maintenance in a hangar

The problem was that while this describes an ideal mission, DASH performance was often far from ideal. In an attempt to reduce cost, most of the control system was entirely non-redundant, so any failure of the electronics, either on the drone or on the ship, meant that a $100,000 DASH2 was going for a swim. Over half of the DASHs ever built were lost in service,3 about 80% to electronic failures, 10% to pilot error, and 10% to other causes. The electrical failures were exacerbated by sensitivity to electromagnetic interference and insufficient maintenance personnel, while a rather clumsy interface contributed to piloting issues.4 And it turned out that the math behind DASH as the cheap alternative to ASROC had a fundamental flaw. An ASROC booster ran about $5000, so in wartime, the drone would pay for itself in just 20 attacks. But DASH required a lot more peacetime training than did ASROC, and in those circumstances, the loss rate, one per 80 flight hours in 1968, was simply unacceptable. That year, production was terminated, and the system was quickly removed from any ship that had another long-range ASW weapon. Critics would later contend that it was accepted for service primarily because it would have been far too embarrassing to not buy it after refitting all of the FRAM destroyers with helipads.

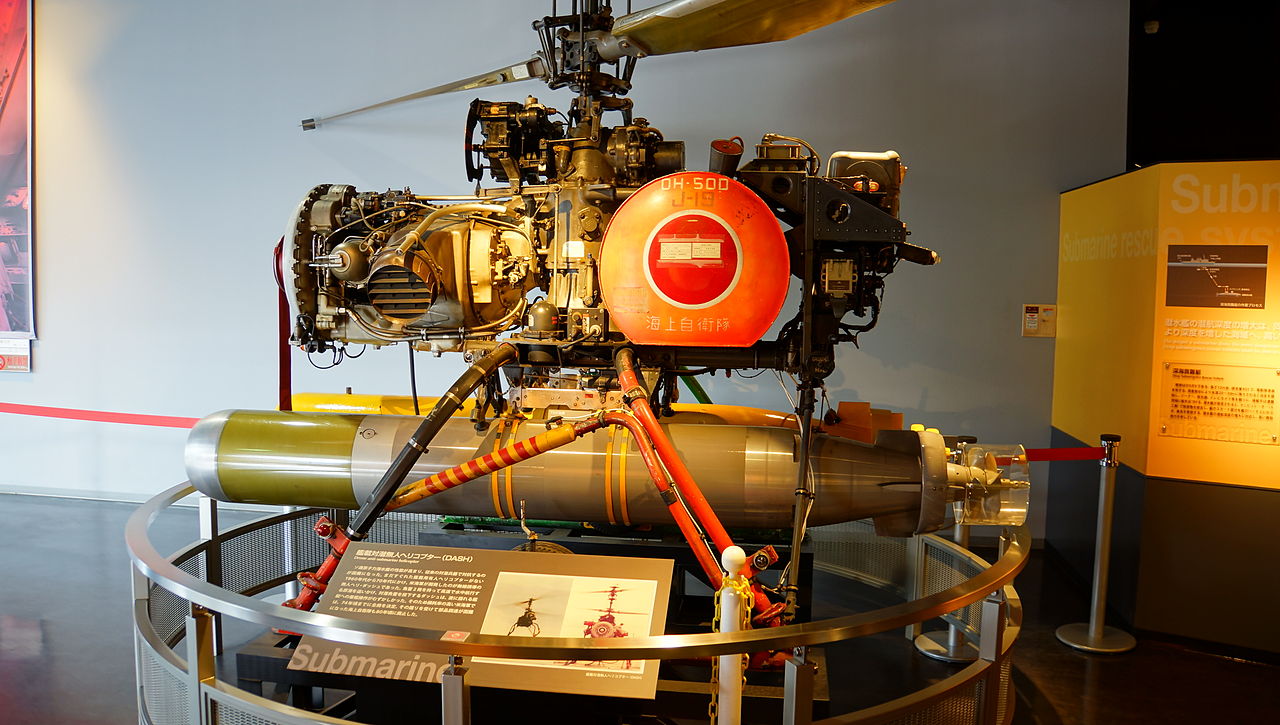

A Japanese DASH

But that wasn't quite the entire story of DASH. A few drones were modified with TV cameras and used to spot gunfire off Vietnam under the codename "SNOOPY". They were reasonably successful in this role, probably because of improved electronics, and pioneered what has since become the defining role for drones. 17 were sold to Japan, which continued to operate them until 1977, with only three reported lost during that time.5 A few ended up in other roles, like calibration targets at White Sands Missile Range, which used them until the mid-2000s.

A DASH with a Fire Scout at Pax River

Even if the reliability issues had been solved, DASH probably wouldn't have lasted all that much longer. Sonar ranges had continued to increase, and any attack on targets out in the convergence zone would require the aircraft to be able to pinpoint a target before dropping the torpedo. While there was an investigation of a DASH variant that also carried sonobuoys, the role instead went to the SH-2 Seaspirte, a small manned helicopter that also carried a surface-search radar, an important feature in a world increasingly concerned with anti-ship missiles. But ultimately, DASH would prove to be ahead of its time. UAVs returned to the fleet with systems like Pioneer in the late 80s, although the focus has remained on surveillance systems. The only real competitor DASH has had in a payload delivery role was Fire Scout, which proved even shorter-lived, but systems like ScanEagle and V-BAT remain a vital part of the USN's surveillance arsenal today.

1 This was before the 1962 merger of Air Force and Navy designations. ⇑

2 About a million dollars in 2026 money. ⇑

3 411 out of 746 by June of 1970, about six months before the program was shut down. ⇑

4 There are reports in credible sources that drones occasionally returned to the ship upside down. I am exceedingly skeptical of this, because even specially-modified acrobatic helicopters don't fly inverted for more than a few seconds. There's no world record on the subject, and we're talking about minutes of flight happening by accident to a drone that was absolutely not designed for it in the first place. ⇑

5 Many sources say no losses, but this is somewhat implausible, even if the Japanese replaced all the electronics, so I will defer to the magnificent Gyrodyne helicopter website for this. ⇑

Recent Comments