Even as Roma and the invasion fleet off Salerno were attacked by the German guided bombs, the Allies began to desperately search for countermeasures. They had first learned of the project from the Oslo Report, sent in November 1939 by anti-Nazi physicist Hans Mayer, who passed the British a document containing information on a number of secret German military projects, including German radars, radio-navigation equipment, and the first hints of what ultimately became the V-2 rocket. The British, viewing the report as too good to be true, disregarded the contents.

An Hs 293

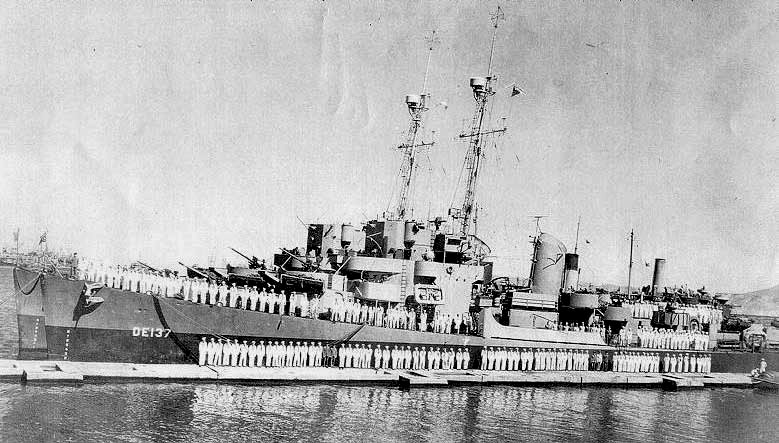

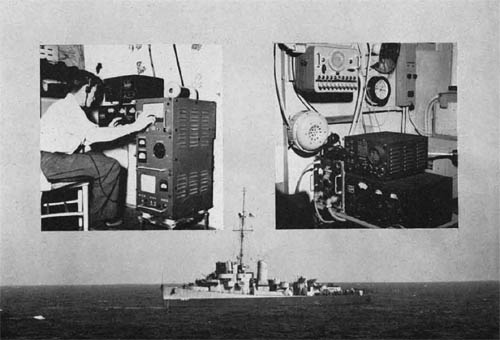

The next warnings came in mid-1943, courtesy of ULTRA, and were taken rather more seriously. Even better, some of the crew from the aircraft shot down over Salerno were captured, giving the Allies some insight into the operation of the system. Recording equipment intended to capture the control signals so countermeasures could be developed was fitted to a few escorts. Unfortunately, the Allies concluded that the Kehl-Strasbourg system worked on frequencies between 10 and 35 MHz, leaving the actual frequency of 48-50 MHz clear. Thus, the first jammers, developed by Howard Lorenzen at the Naval Research Laboratory were completely ineffective.1 However, Lorenzen's team also set to work creating a set of improved receivers to pick up the Kehl-Strasbourg signal. The whole package was installed on the new destroyer escorts Herbert C. Jones and Fredrick C. Davis, which were promptly dispatched to the Mediterranean.

Herbert C. Jones and Fredrick C. Davis at Oran

Even as the ships were steaming towards the combat zone, the Allies scored a major intelligence coup. During a German raid on the Corsican harbor of Ajaccio at the end of September, two Hs 293s failed to detonate, allowing vital components to be recovered from the shallow waters. Even worse, defending Spitfires shot down three bombers, one of which was the only aircraft equipped to monitor for Allied attempts to jam the Kehl-Strasbourg control signals. The losses on this mission, combined with those over Salerno, turned German attention to the hopefully lightly-defended convoys running the length of the Med. Several ships were damaged by Hs 293s on early missions, but kills proved elusive. The most notable victim was the British freighter Samite. Every one of her holds but No. 3 was full of explosives, but the bomb hit square on No. 3 hold, and she survived. Among the escorts of the third convoy attacked were Jones and Davis, and while Jones shot down an He 111 torpedo-bomber, neither had any success in the electronic war with the Hs 293s.

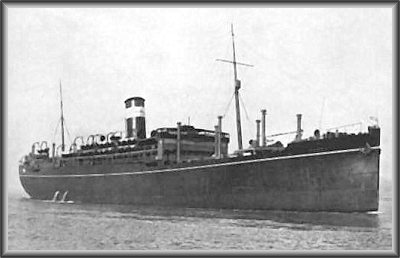

HMT Rohna

Success came in late November, when clean recordings of the Kehl-Strasbourg were made during another convoy attack, allowing the critical frequencies to be identified. This was the second use of the new He 177 in combat, after a previous convoy attack five days earlier, and six were shot down. However, these successes were overshadowed by the loss of the British transport Rohna, heavily loaded with American troops bound for Burma, to an Hs 293. 1,045 US servicemen and 134 men from other Allied nations were killed, approximately half the total number aboard the vessel.2 Ashore, several components of the system were captured as the Allies overran Italian airfields where the guided bomber units had been based, and by December, improved jammers were developed and fitted to a few escorts, including Jones and Davis. While the American XCJ jammer was in the right frequency band, the operator first had to isolate the proper frequency, then tune the transmitter to jam the system, while making sure to jam a different bomb than the other ship.

HMS Jervis

They were just in time to protect another fleet of amphibious shipping, that assembled by the Allies to try to bypass the German defenses in Italy by landing at Anzio. At least 3 ships with XCJs were on station with the fleet at all times, although they were perhaps more effective in giving warnings of raids than in actually stopping the bombs. On the second day of the invasion, the destroyers Janus and Jervis were attacked with Hs 293s. Janus was sunk with the loss of over 100 men, while Jervis, despite losing a good chunk of her bow, managed to escape without a single casualty. The next night, the American destroyer Plunkett avoided glide bombs but was badly damaged by a conventional bomb, and the hospital ship St David was sunk by another Hs 293 with the loss of almost 100 lives. Two days later, the Do 217s managed to damage a pair of cargo ships, but II/KG.40, the He 177 unit, took such a beating at the hands of Allied fighters that it was withdrawn from Anzio.

Spartan bombarding targets at Anzio

On January 29th, the Germans were back, sinking the light cruiser HMS Spartan with a single Hs 293. While this should not normally have been fatal, all power was lost throughout the ship, and she had to be abandoned. The Allies responded with a new tactic, a heavy bomber raid on the airfield at Bergamo, which had been used to stage attacks by the relatively short-range Do 217. It would be a week before the glide bombs would return to Anzio, and when they did, they were mostly ineffective. Only one transport and one destroyer were lost during the month of February, a result which earned Jones and Davis the Navy Unit Commendation.

Jamming equipment fitted to Jones and Davis

Even as the battle was being fought at Anzio, Allied laboratories labored to produce better countermeasures. The British attempted to work around the problem of finding the right frequency by jamming something that didn't change, the 3 MHz intermediate frequency.3 Signals would be transmitted at 47 MHz and 50 MHz, which, when mixed inside the radio, would produce a strong 3 MHz signal that would jam the 3 MHz signal produced by the system. The Americans distrusted this approach, as it relied on correct identification of the intermediate frequency,4 but continued to improve the XCJ and similar jammers to make them easier to tune and more powerful. They did, however, go to work on yet another concept. Off Anzio, the control scheme for the Kehl-Strasbourg had been deciphered, and a transmitter was devised that would automatically detect the control signal, then tune itself to spoof the receiver, steering the bomb harmlessly into the sea.

Ships and landing craft off Normandy

All of these countermeasures were in place by the time of the next great invasion, that of Normandy. Instead of the three jammers that had protected Anzio, over a hundred ships had been fitted with jamming equipment. To back it up, an incredible amount of fighter cover was stacked over the beach. Even more quickly than at Salerno or Anzio, prohibitive losses quickly forced the Germans to abandon the glide-bombing campaign, which met with few successes, even when they tried to use it against bridges. Some units had to be disbanded due to lack of airplanes, and the glide-bombing campaign petered out as the German war effort focused on defensive weapons.

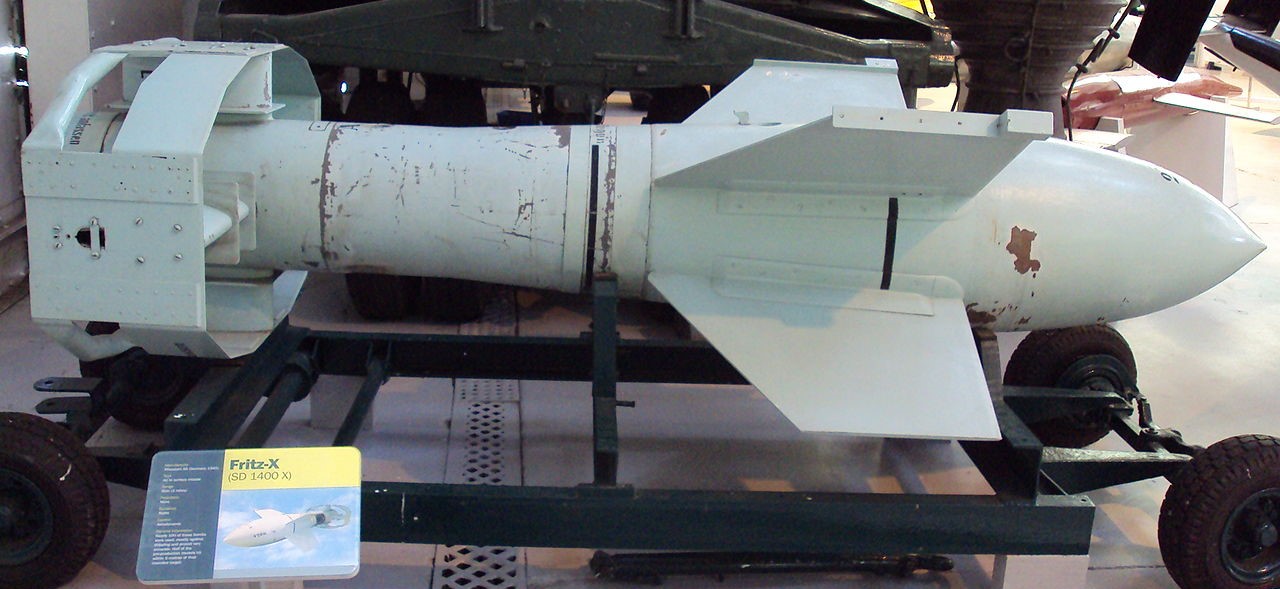

Fritz-X

Ultimately, the Fritz-X and Hs 293 were not particularly effective. Only 13 ships were definitely sunk with five more sinkings possibly attributable to the bombs.5 6 more ships were written off or scuttled, 9 badly damaged, and 12 lightly damaged.6 The cost to the Luftwaffe was high, as the bombers could not take evasive action and suffered serious losses in the face of Allied fighter cover. More than that, the bombs proved vulnerable to relatively simple countermeasures.

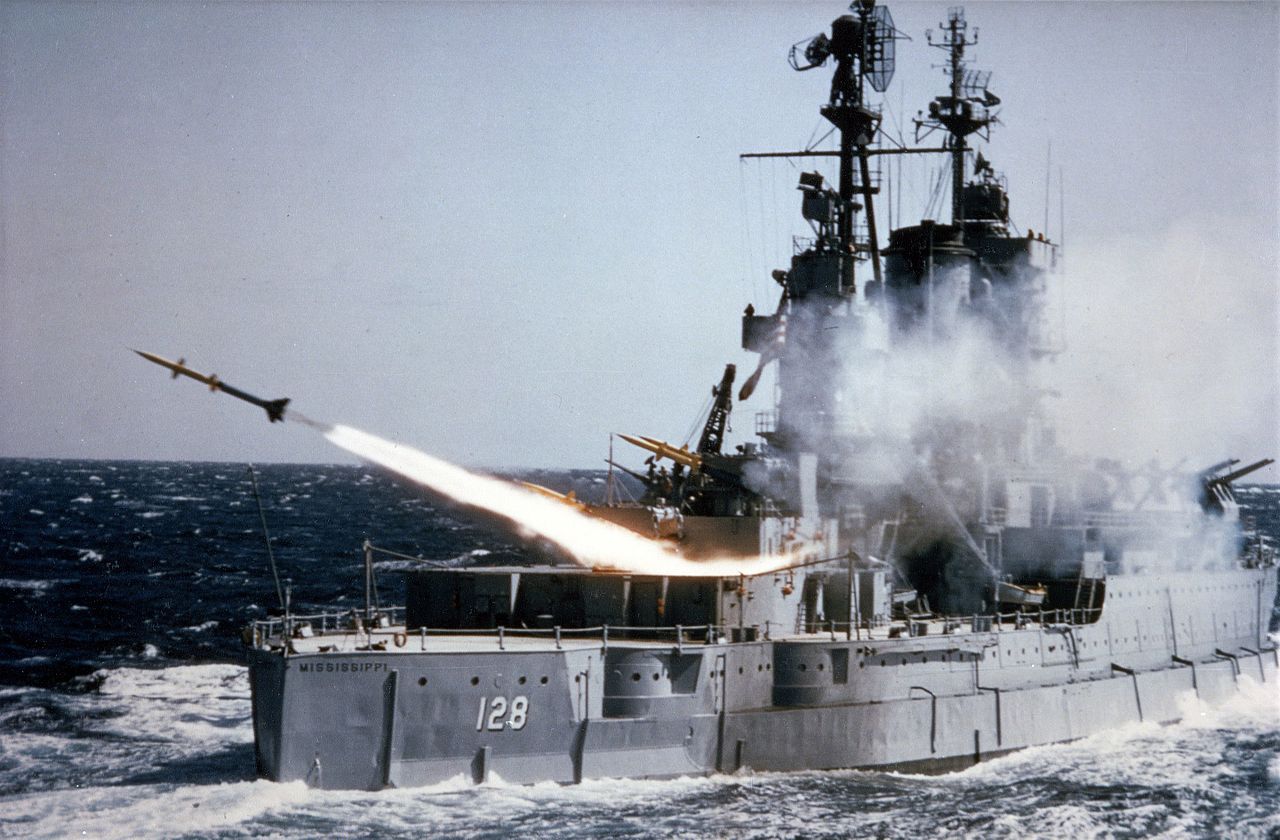

A Terrier SAM being fired from the former battleship Mississippi

In the long run, the biggest impact of the bombs was probably to kick-start the development of long-range air defenses for surface ships operating without fighter cover. Both the USN and RN can trace their naval SAM programs back to the actions off Salerno, although credit must be shared with the Kamikazes for underlining the need for greater anti-air range than could be provided by guns. The Hs 293 and Fritz-X are also notable as being the first successful aerial guided weapons, proceeding the Allied attempts at such munitions into service and ultimately paving the way for the smart bombs and cruise missiles which have revolutionized warfare over the past three decades.

1 There was a rumor that electric razors emitted a signal that jammed the bombs. Nobody is quite sure where or how this came about, and it was almost certainly completely ineffective. But a lot of sailors bought electric razors because of it. ⇑

2 This is the single greatest loss of life in US military history aboard a ship at sea, and the single-ship total is eclipsed only by Arizona. Despite this, the incident is almost unknown. ⇑

3 Radio receivers of the day used superheterodyne receivers which use complicated electrical witchcraft to move the incoming signal to a lower-frequency signal which is easier to deal with. ⇑

4 The intelligence the IF jammer was based on turned out to be correct, but it was a serious risk, probably taken by the British in the knowledge that the Americans were more than capable of handling the brute-force jammer on their own. ⇑

5 It's not always clear what sunk a ship in the chaos of an air attack, particularly as Allied security policies often concealed the cause if it was a guided bomb. My primary source for this series, the book Warriors and Wizards, went into some detail on most cases but couldn't always reach a definitive conclusion. ⇑

6 These numbers include both definite and possible hits. ⇑

Comments

Speaking of the Talos/Terrier missiles, I found https://www.okieboat.com/Talos%20history.html to be fantastic. Does it seem to be an accurate representation of things?

As far as I know, yes. I'm not an expert in US SAM development, but things with that many footnotes are rarely far off. (Actually, when I get around to looking at Talos, that site is going to be one of my sources.)

Germany didn't have the capabilities to do much with them, but these guided bombs strike me as unusually useful wunderwaffen. Based on Fritz X's performance, I have to think that if the US had developed it its record in the Pacific would have been quite impressive.

Given the rather poor state of Japanese air defenses, you might well be right. On the other hand, the US had a very active guided bomb program of its own, most notably producing the autonomous Bat, and by the time any such program would have yielded fruit, there weren't that many Japanese battleships left. Add in that it wasn't suited for carriage by carrier aircraft (you needed a pretty big plane to carry the bomb and all the radar gear) and I can understand why they didn't make extensive use of those weapons.