While gravity bombs of various types are powerful and effective weapons, all of them suffer from one major drawback. They require the launch platform to close with the target, which can take it straight into the envelope of whatever defense systems are protecting it. Guided bombs raise the altitude ceiling, keeping the strike aircraft out of the envelope of short-range SAMs and AAA guns, but these are usually integrated with long-range high-altitude SAMs, which aren’t so easily avoided. The answer is standoff weapons, which hopefully allow the aircraft to stay out of range of the target’s defenses. Generally, these weapons would be used to degrade or destroy the target’s air defenses, opening the way for cheaper, shorter-range weapons. Normally, “standoff” means “missile”, but this isn’t always true, and we’ll start by looking at unpowered standoff weapons, which achieve their range by gliding.

AGM-62 Walleye

The concept of a gliding bomb is not new. The German Fritz-X of WWII was a glide bomb, although it differed from modern weapons of the same type in falling quite steeply. Several other nations also built more conventional glide bombs during and immediately after WWII, with only limited success. The 50s saw little work on weapons of this type, as nuclear weapons greatly reduced the need for precision guidance. During the 1960s, this kind of logic was seen as no longer appropriate, and programs began to develop new precision weapons, taking advantage of electronics unavailable to their WWII-era predecessors. These bombs, like the Air Force HOBOS and Navy Walleye, were designed with some glide capability. Both used contrast seekers, which used an analog TV camera set up to look for sharp changes in image value and home in on them. This was pretty effective when it worked, but it required the target to stand out clearly from the background, meaning it was limited to daylight and good visibility. The need to lock the seeker on before launch meant that the airplane often had to get rather closer than it would have liked to the target, and the weapons themselves were considerably more expensive than Paveway, so they saw only limited use during the Vietnam War.

An F-4 drops a GBU-15

Postwar, effort went into solving the lock-on problem by fitting a data link back to the launching airplane. This let someone1 use the weapon's own TV camera to either get it close enough for the contrast seeker to take over, or just fly the weapon all the way to the target. Walleye was upgraded with this capability, while the Air Force created the GBU-15 by mating a Mk 84 to a TV seeker, wings, and a datalink. This was then further improved by fitting it to a rocket, producing the AGM-130. But the glide bomb didn't really come into its own until the 1990s, when guidance electronics became cheap enough that eliminating the cost of the engine could produce substantial savings in the cost of the weapon, bridging the gap between cruise missiles and direct-attack weapons like JDAM and Paveway.

An AGM-154 JSOW

The first of these weapons was JSOW, the imaginatively-named Joint Stand-Off Weapon. The initial version, AGM-154A, was an 1,000 lb unpowered glider loaded with 154 combined-effects cluster bomblets and guided by the same GPS/INS technology that JDAM used. The bomblets made it highly effective against targets like SAM sites and troop concentrations. It could glide 12 nm if released at low altitude, and as much as 70 nm from high altitude. Its development was one of the most successful weapon procurement programs of the 1990s, with the weapon entering service a full year ahead of schedule in late 1998. Today, it's often studied in an attempt to help the performance of other programs. The first operational use of JSOW was against Iraq during Operation Desert Fox, one of the interminable actions to punish Saddam's regime for interfering with the UN weapons inspectors.

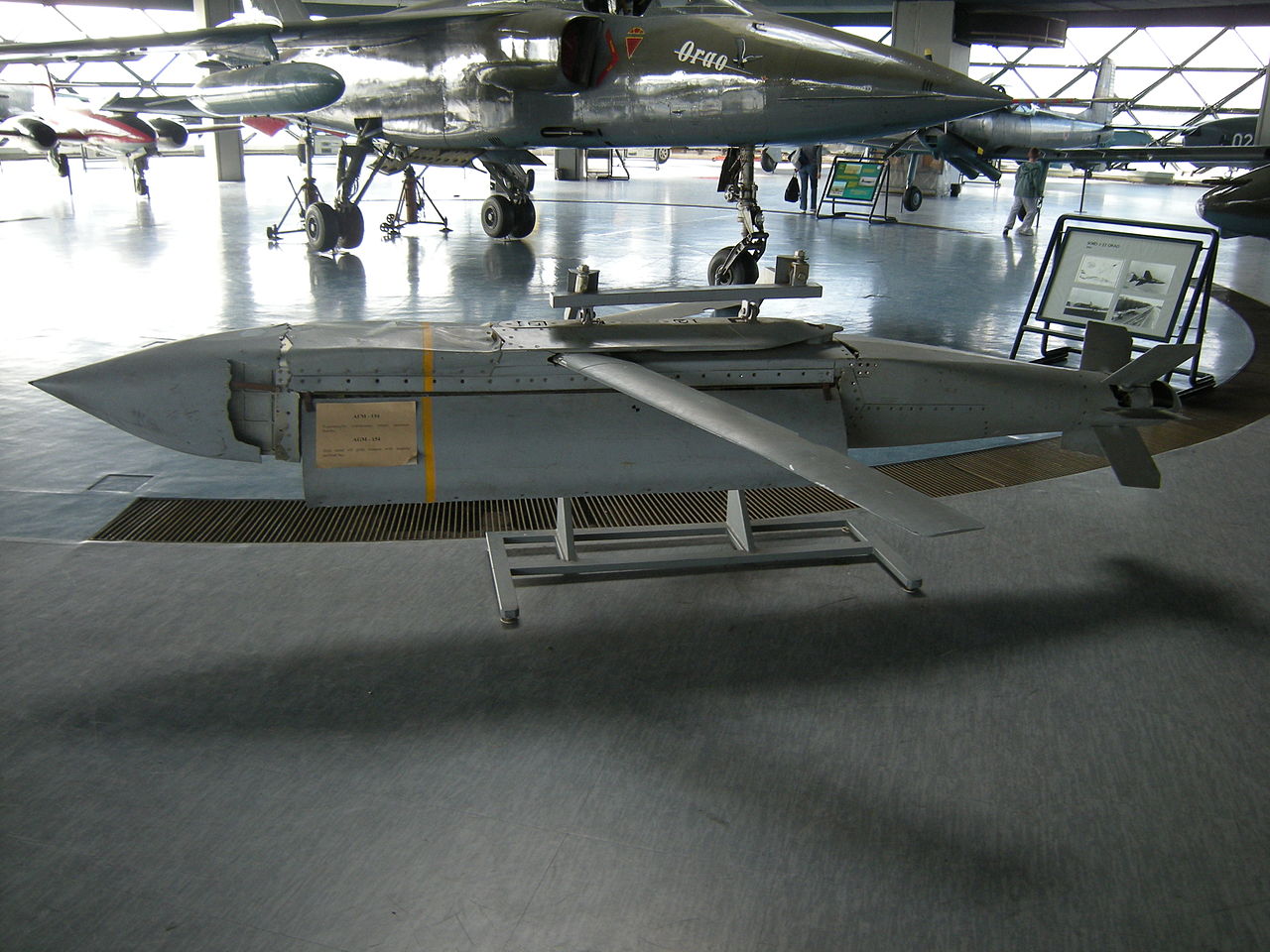

An AGM-154A JSOW used against Serbia, now in a museum in Belgrade

From the start, JSOW was designed to function as a "truck", with easy integration of various payloads. The first attempt at this was the AGM-154B, which would carry a batch of BLU-108 smart submunitions intended specifically to target tanks and other vehicles. Development was completed, but the Air Force decided to retire JSOW in 2005 instead of buying some, and the Navy preferred to spend its money on other things, such as a third variant, the AGM-154C. To get around the increasing concerns about the use of cluster bombs, this one was fitted with a unitary (non-cluster) warhead and an imagining infrared (IIR) seeker that can compare a potential target's shape to a model stored in its database and automatically lock on. The warhead is a design known as BROACH, where a shaped charge opens a hole in the target, which the rest of the warhead then flies through before detonating.

A JSOW is brought up the weapons elevator to a carrier's deck

Today, JSOW remains the Navy's primary standoff weapon, as well as serving with many of our allies, from Australia and Singapore to Finland and Saudi Arabia. The latest version, the AGM-154C-1, has a two-way data link which allows it to be retargeted in flight, making it an effective weapon against ships as well as land targets. A plan was also in the works to fit JSOW with a small engine, turning it into a proper cruise missile2 and extending the range to as much as 300 nm, but it was cancelled and the Navy rejoined the JASSM program instead.

An AGM-154C-1 dives into a ship during a test

The second of the modern glide bombs began in an attempt to solve a simple problem. Carrying weapons externally, as most modern aircraft do, tends to make stealth aircraft much more visible to radar. The obvious way around this is to carry the weapons internally, which sharply limits the volume available, and thus the number of weapons that can be carried on a given sortie. But if bombs could be made smaller, then a stealth aircraft could carry a reasonable number in the bay, with improved guidance offsetting the reduction in warhead size.

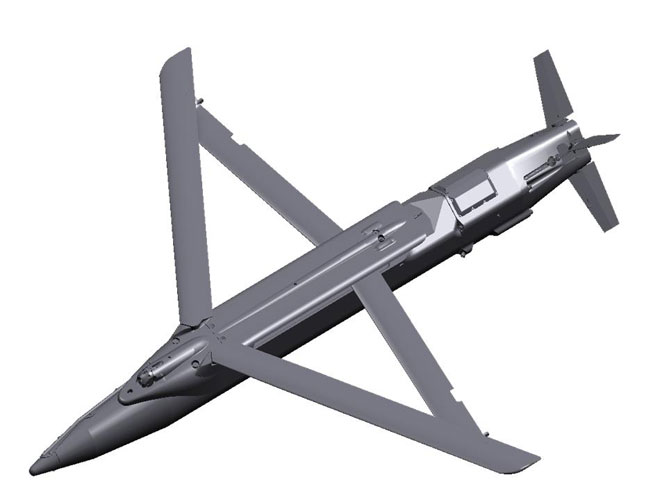

GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb

The result of this was the GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb, probably the most important munition developed so far this century. At 70" long, 7.5" in diameter, and 285 lbs, eight can fit into the weapons bay of an F-22 or F-35, replacing a pair of Mk 84 bombs. After release, the DiamondBack wings pop out, giving it a range of 60 nm or more from high altitude. The 36-lb warhead requires it to hit its target with a degree of precision that standard GPS/INS can't quite manage, so nearby ground stations provide differential GPS data to the launching aircraft by a datalink. This is then passed to the weapon.

Four SDBs share an F-22's weapons bay with an AIM-120 AMRAAM

SDB is designed to give maximum versatility, so it has a programmable fuze with modes ranging from proximity airburst to contact and hard-target delay. For hard targets, it can pierce about 5' of concrete, making it competitive with the BLU-109, aided by a reported feature known as Optimal Guidance. This apparently aligns the axis of the bomb with the velocity vector just before impact, making sure it hits nose-on and increasing penetration. The standard ejector carries four of the weapons and fits on the same pylon as a standard 2,000 lb bomb, greatly increasing the number of weapons a strike aircraft can carry.

An SDB demonstrates its ability to penetrate hardened targets

SDB development began in the late 90s, and in 2001 Boeing was awarded the contract for the weapon. Despite its complexity relative to something like JDAM, initial operational capability was reached in only five years, as a weapon of this type was desperately needed to hit urban targets in Iraq. Today, a buy of over 10,000 weapons is underway, at a unit cost somewhere in the region of $70,000 each. Boeing has also developed several variants of the SDB, including one that is fitted out to home in on GPS jammers, a major concern as the US military becomes more reliant on GPS. The most important variant is known as the "Focused Lethality Munition", which is designed to address the fact that even SDB is too big for some urban targets. The FLM uses a special warhead designed to minimize collateral damage, using something called Dense Inert Metal Explosive, tiny particles of tungsten alloy suspended in a block of explosives. When the warhead goes off, these are fantastically lethal at close range, but are rapidly slowed by air resistance, keeping bystanders safe.3

SDB IIs loaded on an F-15E Strike Eagle

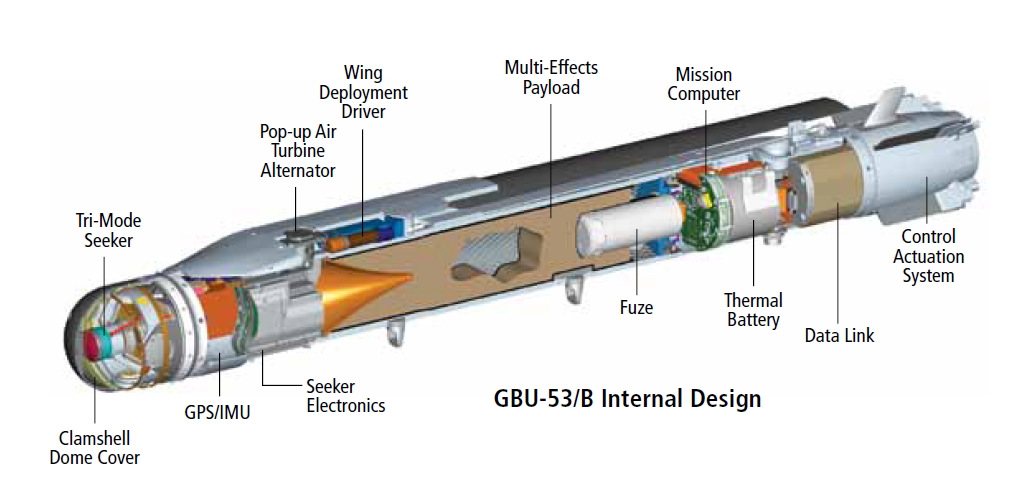

But SDB shares the common drawback of all GPS-guided weapons, an inability to attack moving targets. This is a capability the military would very much like to have, and a program to fit something SDB-sized with a seeker capable of going after moving targets was started in parallel with the original effort. The military, displaying its usual genius for naming, called this SDB II,4 and despite delays due to a corruption scandal, Raytheon was awarded the contract in 2010. SDB II is fitted with a tri-mode seeker combining millimeter-wave radar, imaging infrared (IIR) and laser homing, giving the operator lots of options. The radar is capable of working in conditions of zero visibility, and the IIR can autonomously classify targets, allowing it to select the highest-priority options for destruction. This makes it the first weapon capable of properly enforcing no-drive zones.5 The warhead is multi-purpose, incorporating a shaped charge to destroy armored vehicles as well as the standard blast and fragmentation options. SDB II is also fitted with a data link, allowing it to be retargeted in flight, and to pass information back to the launching aircraft. It's no bigger than SDB I, and has similar flight characteristics. SDB II only entered service in fall 2020 with the F-15E Strike Eagle, but it's an exciting weapon and one that both the Air Force and Navy are looking forward to integrating on other aircraft.

A cutaway of the SDB II

JSOW and the SDB family form an important part of America's aerial arsenal, as well as serving with our allies worldwide. They aren't the only glide bombs in use today, but the last weapon of that type currently in service, the GBU-44 Viper Strike, is a very small weapon primarily used by UAVs, and doesn't merit discussion here. Next time, we'll turn to powered weapons, which trade higher cost and weight for greater standoff from hostile air defenses.

1 Most often, these weapons were employed by two-seat aircraft whose backseater guided them in, but a few single-seat planes did make use of them. ⇑

2 Interestingly, the weapon's designation suggests that this may have been planned from the start. Normally, the missile sequence is for powered weapons only, and JSOW should have gotten a GBU designation instead of an AGM designation. ⇑

3 There's also a variant with laser guidance to allow it to attack moving targets, although details are sketchy at best. ⇑

4 Raytheon's marketing people have tried to dub it Stormbreaker, a name I can't take seriously on several levels. Mostly because it was supposed to be called Cerberus after the tri-mode seeker before a Raytheon exec saw Infinity War. Everyone just seems to call it SDB II. ⇑

5 This is exactly what it sounds like, a zone where the US doesn't want people driving cars. Walking is presumably OK. ⇑

Comments

I am not an expert, but it seems like the combination of precision and standoff range have significantly tilted the table in favor of acquiring more aircraft, in order to have more coverage/longer coverage, rather than traditional bombers that are able to deliver large amounts of ordnance on target at a single time.

Obviously there is some value in having B-52/B-1 level capabilities, but it seems like that has shifted to toting standoff cruise missiles and things, as I can't think of how you could employ 35 tons of bombs in even the most target rich environment.

I'd actually argue the opposite: standoff range in particular increases the utility of traditional bombers. True, you no longer need to deliver big piles of bombs to one target, but standoff range allows a bomber to hit a lot more potential targets in a single sortie. Instead of having to fly almost directly over your target, you just need to approach it to a distance of dozens or hundreds of miles. And as long as you're there, if there are other targets anywhere in the cone of targets your standoff weapons can reach from your launch point (or anywhere else on your course), you may as well hit those too as long as you're in the neighborhood.

A bomber is capable of carrying a lot more precision/standoff weapons than a fighter, and over longer distances. For instance, a typical fighter can carry maybe 4 2,000 lb bombs. (Yes, it's theoretically rated for more than that, but the combat radius isn't going to be much longer than the takeoff run if you do.) You're looking at 20-24 similar weapons for the bomber, and it can be based a lot further away, which is good for your logistics. In a hot war, those bombs are going to be replaced with JSOWs or JASSMs or something of that nature, and in that case, being able to put a lot of missiles in the air at once is really handy.

Piggybacking off what Eric said, you have to look at the bomber less as a target-specific mission vehicle and as more of a general resource to be employed (sort of like a ship) with targets designated by others as they present themselves. Rather than having f35s sent on sorties every time you want something bombed, a B52 just loiters around a few hundred miles out and swings in to drop bombs as requested, giving you a lot of flexibility and a quick response time.

@Chuck

That's how they use bombers for CAS, but it's not really practical in a hot war. Strike missions require a lot of planning, and while more people onboard make it easier to replan things in the air, you're not going to have a bomber orbiting somewhere just waiting for a request for JASSMs. Too expensive and not enough endurance.

I happened to have just read a case study on the development of the JSOW weapon. Serious out of the box thinking. The wings? They were built by a surfboard shop in southern California. The fuselage? A sports equipment manufacturer near Boston that knew how to work carbon fiber. Interesting story.

The range point in particular is good!

Could you point me to that study? Google isn't showing anything on it.

Presumably this should read "imaging"?

Yes, it should. Oops.

Mastering the Leadership Role in Project Management: Practices that Deliver Remarkable Results, by Alexander Laufer.

Found it on Amazon, free Kindle book.

The Fatherly One, I see that book for $38 on kindle, can you link to the free version please?

Gareth,

I downloaded this in 2012. Not sure how to get it to you. Any ideas?