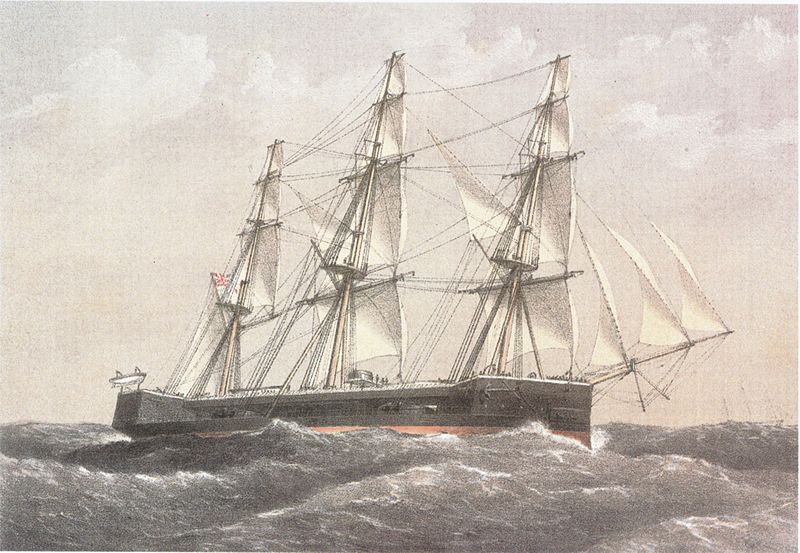

The mid-1860s saw extensive debate in Britain over how to take turrets to sea. The inventor of the turret, Cowper Coles, whipped up public and political support for his vision, putting him at odds with Edward Reed, the Chief Constructor, and Robert Spencer Robinson, the Controller. Their attempt at building a turret ship, Monarch, worked quite well, but Coles had the backing to get a second vessel, Captain, built to his own design in a private shipyard. It was considerably lower to the water than Monarch, and completed heavily overweight. Although none of the players knew it, it was a disaster waiting to happen.

HMS Captain

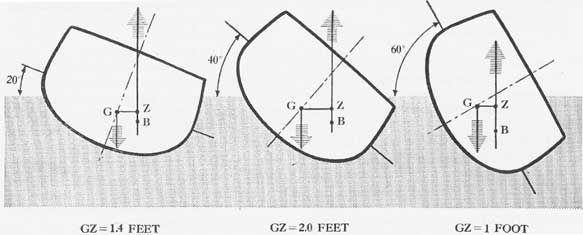

All of this took place against the background of rapid developments in the theory of naval architecture. For centuries, stability had been calculated by guesswork and rule of thumb, and it was only around 1860 that any serious work was done to place it on a scientific and mathematical footing. The concept of metacentric height, a direct measure of stability, was well-known, but no calculations were made for Captain. To make matters worse, metacentric height stops being an accurate measure when the edge of the deck reaches the water, a limitation that was not fully appreciated at the time. To gain data for future ships, Laird requested that Captain be inclined, her metacentric height measured by moving known weights across the decks and the angle of heel produced recorded. This was done in late July 1870, although it took nearly a month for the results to be calculated,1 and even these were not enough to alarm anyone. By this point, Reed, feed up with political attacks on him, had resigned from the Admiralty to resume his career as a ship designer for private yards.

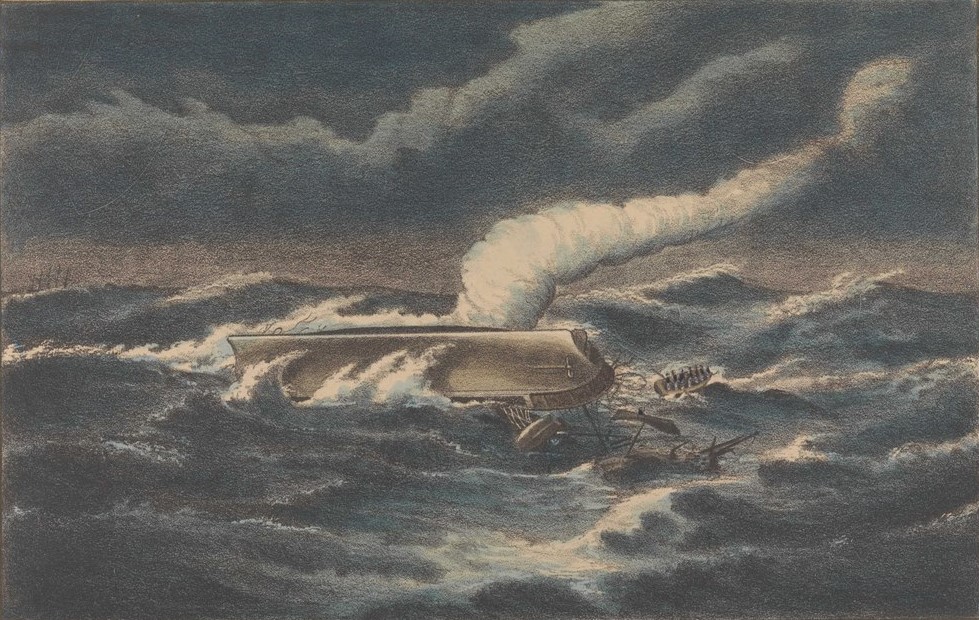

Captain capsizes

On August 4th, 1870, Captain sailed as part of a fleet bound for Gibraltar, to take part in further trials with Monarch. Onboard was Coles, along to watch his prized vessel. On September 6th, two days after the final payment was made to Laird's, the fleet commander, Admiral Alexander Milne came aboard for a visit while the ships were off Cape Finisterre. He was unpleasantly surprised to find that he could step from his boat directly onto the deck, but Coles assured him that there was no danger, and that the water could come as much as 8' past the edge in perfect safety. Unfortunately, this couldn't have been further from the truth. That night, a gale blew up, but nothing that was considered out of the ordinary. In the early hours of the next morning, Captain was struck by a strong gust, and rolled over a bit too far. She never recovered, turning turtle and killing all but 18 of the 500 or so onboard, Coles among them.

A court-martial was immediately convened, and the survivors placed on trial for losing their ship.2 The Court-Martial quickly established several causes for the loss. One was that Captain was carrying too much canvas when the storm hit, possibly at Coles' suggestion, and the narrow hurricane deck over the turrets had hindered efforts by the crew to reduce sail in the last moments before the disaster. Normally, something would have carried away, reducing pressure aloft, but Coles had insisted on strong iron masts and heavy spars. But the real culprit was the narrow range of stability resulting from the low freeboard. Normally, the force trying to right a ship increases as it heels, at least until the edge of the deck goes underwater. Captain was easily driven to that point, about 14° in normal operations, and the righting force began to decline thereafter. A sudden gust was enough to tip her past the point of no return, which was calculated to be at 34°. Monarch, on the other hand, had her maximum righting arm at around 40° of heel, and the resulting change in design standards persists today. Even more importantly, they found that the ship had been built against the advice of Reed, Spencer Robinson, and the other professionals due the pressure of public opinion.

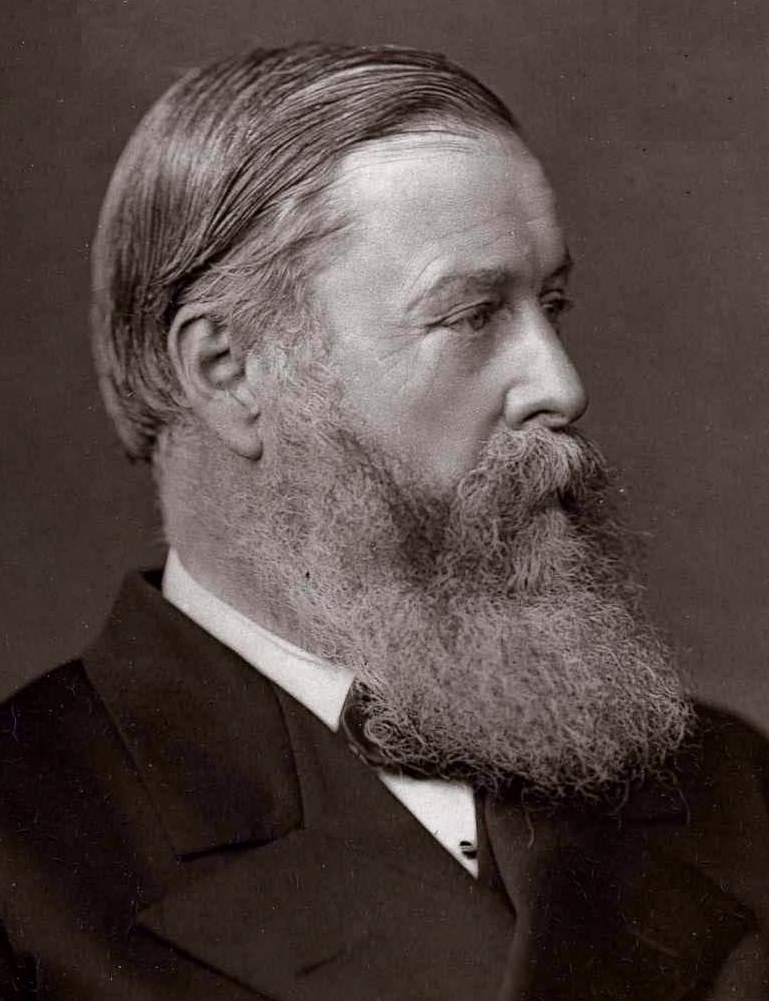

Hugh Childers

The loss of Captain and the verdict of the Court-Martial sent shockwaves through the naval establishment. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Hugh Childers, had been a prominent backer of Coles, and his son, a Midshipman, had been among the victims of the disaster after Childers had arranged a transfer from Monarch. Childers quickly issued a statement blaming Spencer Robinson for not having forseen the disaster and taken steps to prevent it, and ultimately had him fired. To bolster his position, he also announced a committee to evaluate the other ironclads, and the whole practice of British ship design. This was widely seen as an attack on Reed and Spencer Robinson, but the committee3 proved surprisingly fair and forward-thinking, confirming the safety of the other ironclads, and recommending that designs like the mastless Devastation make up the bulk of the future fleet, with a network of coaling stations worldwide to support them. This was controversial, and several naval officers on the committee dissented.

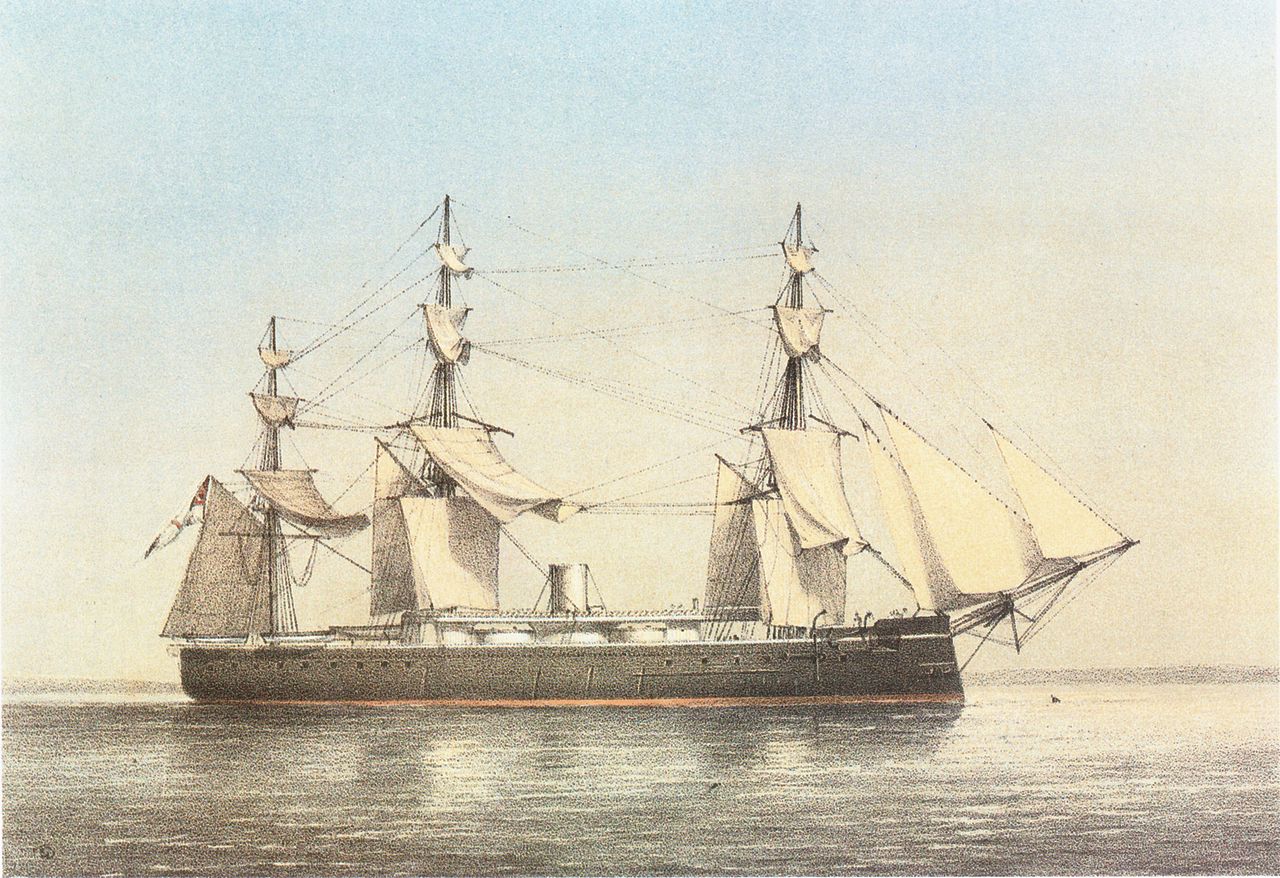

HMS Monarch

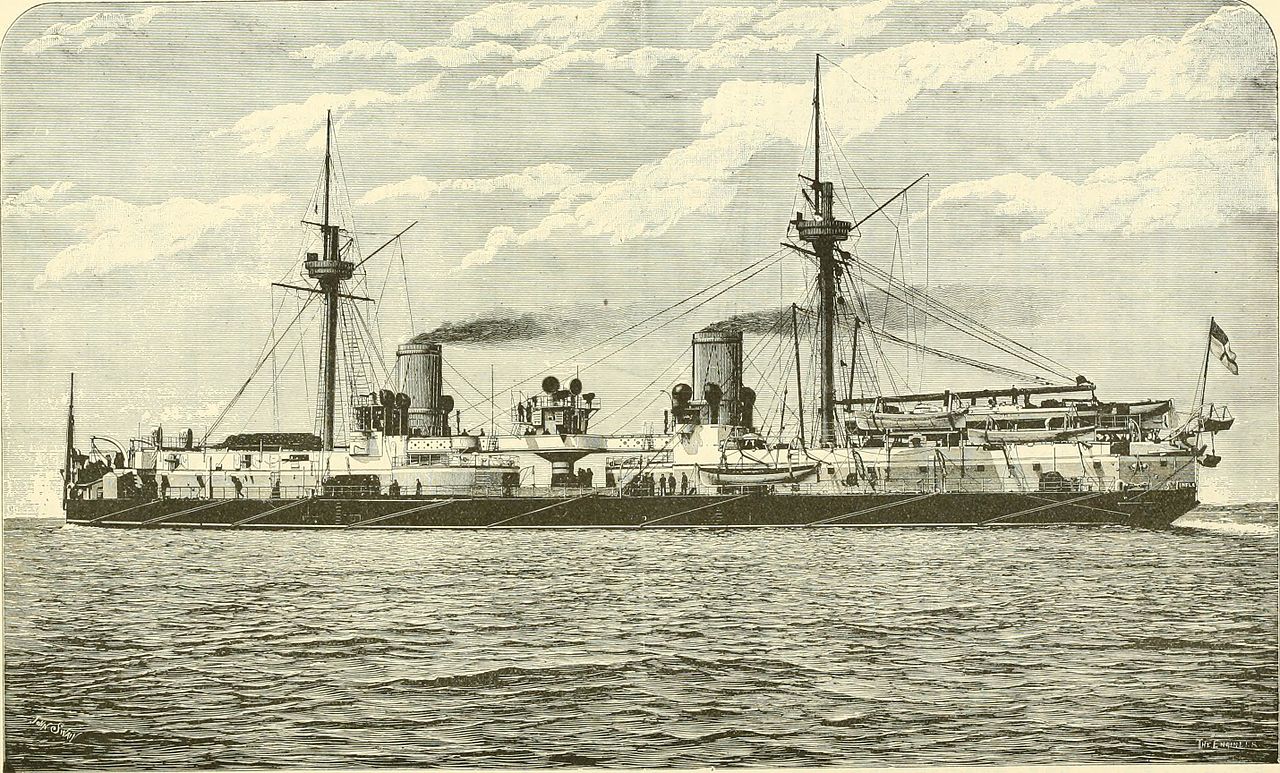

In fact, only three more sailing battleships would be built, Alexandra, Temeraire and Inflexible. The first two vessels had central batteries, and Temeraire also pioneered the barbette in British service. Inflexible did carry turrets, but in a very different configuration from Captain, and with only two masts, a clear sign of the decline of sail as a means of propulsion. In service, they were rarely used, and were removed entirely in 1887. All three of these ships were the work of Nathanial Barnaby, Reed's successor. Reed never equaled his earlier ships after his resignation, and instead spent most of his time unfairly criticizing his successor's designs, particularly after he was elected to Parliament. Childers resigned shortly after Spencer Robinson, claiming ill health, but he later returned to several other political posts, including Chancellor of the Exchequer. Monarch herself had a long and reasonably successful career, taking part in the 1882 bombardment of Alexandria.

HMS Inflexible

So what lessons can we draw from all of this? The most important lesson is that public opinion is not well-informed about defense policy, and the views of professionals are neglected at our peril. Captain provides an unusually stark example of all of this, but the last 150 years are rife with other cases where political objectives were allowed to override sound defense policy, always to the regret of those who allowed it to happen.

1 D.K. Brown, a naval architect trained in many of the methods used at the time, stated "Some writers have unjustly criticized him for the time taken, but such critics have never used Barnes' (the constructor responsible) methods by hand. I have." (Warrior to Dreadnought, p.50.) ⇑

2 While this seems like an obvious injustice today, at the time it was the standard method of holding a court of inquiry, and was done any time a ship was lost. If the circumstances of the loss were not the crew's fault, they had nothing to fear and would easily be let off. ⇑

3 Notable members included William Froude, Ernest Thompson (later Lord Kelvin) and William Rankine. ⇑

Comments

This not the first case where a brand new ship, made to a new standard, pride of the fleet etc. just falls over and sinks on the maiden voyage.

Vasa https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasa_(ship)

I was under the impression that it was still normal practice in the RN to court-martial a captain who lost his ship.

It turns out that this hasn't been the case since WW1.

Here is the First Lord of the Admiralty speaking in Parliament about the sinking of HMS Glorious in 1940:

Captain was significantly more stable than Vasa, as she didn't go over until a major storm, but she also had two centuries worth of improvements in naval architecture. I don't know much about what happened with Vasa, as it's outside my horizons in the age of sail.

@AlphaGamma

Although if there was ever a solid case for court martialing the captain of a lost ship, then HMS Glorious was it.

But the political motivation is pretty obvious to not make a lot of noise about a major defeat, in the context of a generally disastrous campaign, involving a WW1 Victoria Cross decorated war hero.

Reading Warrior to Dreadnought, I was wondering how hard it would be to drive an ironclad's sailing masts right through the middle of the (twin) turrets. IE the turret revolves around the mast, which rises through the top of the cupola.

This would reduce congestion on the ship's centerline and give the turrets fields of fire much like modern dreadnoughts. The mizzen turret would train aft and sideways. The turrets under the fore and main masts would be broadside only, but with more room. A different arrangement would be needed for the bowsprit - either the foremast turret can fire over it, or maybe a revolving mount in a casemate with firing ports forward and sideways.

Is there something fundamentally wrong with this, or was it just that sail was no longer relevant by the time turrets came into widespread use?

You'd be putting the mast really close to the blast of the powerful gun, that might not be such a good idea.

What exactly do you mean by the mast goes through the turret?

I think that either means the mast passes through a hole in the top/bottom of the turret (layout a) or the the mast is structurally mounted to the top of the mast (layout b).

Layout a is messy for the turret - probably have to increase turret diameter by a factor of between 1.5-2x to account for the fact that you're trying to still load a gun w/ a big mast post in the way - this probably increases costs by a factor of 10x if you can get it to work - large diameter bearings are not easy to build. You potentially run into issues noted by the previous commenter of deliberately introducing gun firing loads into structure next to the mast - which can probably be design for, though if you have a magazine/barrel explosion you probably loose the mast. Increasing turret diameter is not your friend, as one of your key design requirements for this was not to take up precious centerline space.

Layout b is almost certainly impractical, you just flat out can't practically design a bearing that is capable of carrying a ship's mainmast worth of applied moment out and still function as a useful bearing.

@Anonymous Not really? The mast would go through the inside of the turret, you know, where the gunners are. The blast is outside, in front of the muzzles. If anything, this setup protects the lower part of each turret's mast, from blast from the other turrets, not to mention enemy fire.

@ryan8518 I mean option a. The mast is connected to the ship, happens to have a turret around the point where it emerges from the deck.

The turret would be larger, but half again strikes me as unrealistic. Assuming a twin turret, the mast goes in between the guns, which recoil on either side of it. Might need to rearrange some things, but sounds doable. Don't see why it would double anything.

Losing the mast is the smallest of your worries at that point, no? And they didn't use sail in battle, so no biggie.

The blast is outside. The recoil is absorbed by the guns' mountings, right? A turret that shakes on firing sounds unsound, and definitely unhealthy for the gunners.

This does not seem like a good idea in practice, although I'm sort of surprised that nobody tried it back then. I think the biggest issue is that masts generally need supports and stays. This was an issue for Monarch, and for battle, they'd take the topmasts down and remove a lot of the stays to increase field of fire. Captain got around this with tripod masts, but those had other issues, and would still restrict arcs some. And you need to work the sails, which the turret might complicate. I'm not sure how you'd, say, bring the topmasts down with the turret in the way. (But I'm also not an expert on sail seamanship, so I'm a bit fuzzy on that process in general.)

There's also potential structural concerns, as the turret and mast both need to be supported, and I'm not sure that the mast wouldn't get in the way of turret operation. Those were pretty cramped inside.

@AlanL Either way, it'd be a moot point in that case; Captain D'Oyly-Hughes went down with Glorious.

And you need to work the sails, which the turret might complicate. I’m not sure how you’d, say, bring the topmasts down with the turret in the way. (But I’m also not an expert on sail seamanship, so I’m a bit fuzzy on that process in general.)

Perhaps you could have a flying deck over the turret, like on HMS Monarch.