In the search for material for this year's Jutland post, I read Andrew Gordon's The Rules of the Game - Jutland and British Naval Command. It's a massive book that grapples seriously with the question of why the British Admirals at Jutland acted the way they did, and it goes a lot of very interesting places. But ultimately, I didn't feel that I could do it justice with my usual method of drawing directly from sources without taking a lot of posts, so I will instead review it.

Naval Officers of World War I by Arthur Cope

Rules of the Game is many things. It's a critical look at Jutland, a social history of the RN's late Victorian officer corps, an investigation of their signalling and command practices, a detailed account of the circumstances surrounding the loss of HMS Victoria, a biography of Hugh Evan-Thomas and a meditation on the sorts of flaws that military organizations tend to have in peacetime. It's also 600 pages, but Gordon does an excellent job of bringing his threads together in the last chapter, making the whole book possibly the best presentation I've ever seen of some of the deeper structures of military theory I've talked about before.

Gordon starts his quest to figure out why officers up and down the chain of command so thoroughly lacked initiative at Jutland with a detailed account of the opening phases of the battle, ending when Beatty turned north and Evan-Thomas failed to follow for several critical minutes, exposing his ships to heavy fire. Then, with that framing, he launches into a complicated historical odyssey covering a great deal of the second half of the 19th century, before returning for a look at the rest of the battle, it's aftermath, and the lessons we can draw from it today. It's a wild journey, but one I enjoyed immensely.

Hugh Evan-Thomas

The thread that ties all of this together is the conflict between authority and initiative, and Gordon's thesis is that the century between Napoleon's defeat and the outbreak of WWI saw authority triumph almost completely, leaving the RN's officer corps unprepared for the chaos of combat. While some degree of this was inevitable in the long peace, Gordon places a great deal of emphasis on the development of flag signalling in the 19th century. The system first developed by Home Popham had greatly increased the vocabulary available to Admirals, who rapidly began to exercise far more control over their fleets. At Trafalgar, Nelson had sent only three signals, the immortal "ENGLAND EXPECTS EVERY MAN TO DO HIS DUTY", "PREPARE TO ANCHOR AT CLOSE OF DAY" and "ENGAGE THE ENEMY MORE CLOSELY". Some of his subordinates thought that even this was too much. By the closing years of the century, a fleet maneuvering together would involve dozens of signals, with ships maneuvering precisely as the Admiral desired, and Captains judged on how well they could execute orders.

Not every officer thought that this was a good idea, the most notable exception being George Tryon, who took over as Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1891. Tryon was concerned that signalling took too long, and would likely break down entirely in battle, as halyards were shot away and visibility fell due to smoke. He began to drill the Mediterranean Fleet on a simpler system, where subordinate divisions were simply instructed to follow the flagship's movements, ready to take the initiative if they saw the chance. This worked fairly well, although the more authoritarian Admirals objected, and any chance it had of catching on more widely was scuttled when Tryon botched his maneuvering and died when his flagship Victoria sank after being rammed by HMS Camperdown. In the ensuing controversy over whether or not Camperdown acted improperly by not disobeying orders, the obedience side won, and several mid-grade officers who took part in the events in the Med, including Jellicoe and Evan-Thomas, would go on to play leading roles at Jutland. Evan-Thomas is given particular emphasis, as he was heavily involved not only in the development of signalling but also benefited from being a close companion to the Dukes of Clarence and York, the latter of whom would eventually be crowned as George V.

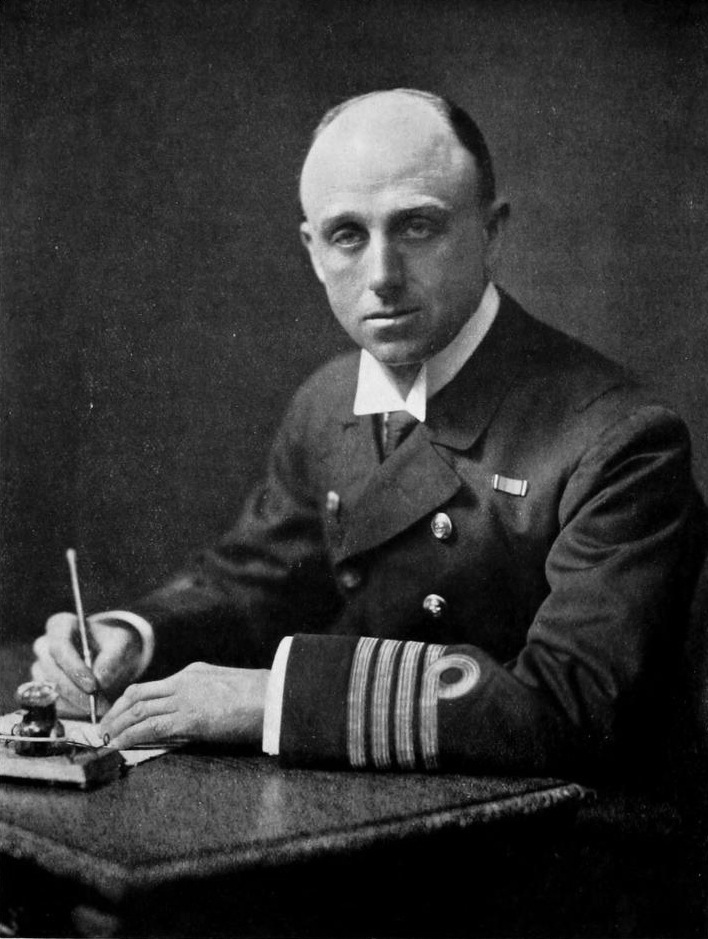

Robert Arbuthnot

All of this would cause serious problems when the two fleets finally met in battle. While the Grand Fleet accomplished its fundamental mission of maintaining the blockade, Evan-Thomas passed up several obvious opportunities for lack of orders, most notably not turning to follow the battlecruisers when the Germans were first sighted and then delaying the turn north (which Gordon suggests was probably because Beatty's rather terrible flag lieutenant simply forgot to haul down that signal for a couple minutes). More broadly, British officers generally failed to do anything in the absence of orders, with the notable exception of the pugnacious and (literally) pugilistic Robert Arbuthnot, who took his armored cruisers into the space between the two fleets in pursuit of Weisbaden and died along with every other man on his flagship, Defence, when she came under fire from much of the High Seas Fleet. The problem became even more obvious during the night action, when ship after ship failed to fire on German vessels even at point-blank range due to a lack of orders.

The one exception Gordon brings up to all of this is Beatty, who he places firmly on the initiative side, citing things like the difference between Jellicoe's detailed Grand Fleet Battle Orders and the far less formal procedures Beatty produced first for the battlecruiser force and later after he took over the Grand Fleet. He cites Beatty's rather odd career history, rescued from mandatory retirement only because Churchill liked him, as the reason he was able to reach such a high position despite his fundamental disagreement with the culture of the broader RN. In this, I think Gordon is probably kinder than Beatty deserves. Whatever his theoretical virtues in opposing the problems in the RN's officer corps, his performance at Jutland wasn't great, and his attempt to burnish his reputation after the battle was hilariously self-aggrandizing, while Jellicoe made the right decisions at the right time to keep the blockade intact and win Britain a strategic victory.

David Beatty

So, with all of that said, should you read it? The first 24 chapters include two very good books, one on the organizational culture of the RN in the years leading up to WWI, and another a critical reappraisal of Jutland. Even though they're mixed together, and with a lot of diversions, I enjoyed that section, and would recommend it if you have interest in either side. Then came Chapter 25, in which Gordon brings everything together in a tour-de-force that is probably the best breakdown I've seen of how peacetime rot can set in in a modern military. It wouldn't work nearly as well without going through the process Gordon does to get there, but it significantly improved my gut understanding of this stuff, which I've been feeling my way around the edges of for some time. Cassander likes to mention attending a talk by Secretary Mattis where he recommended two books, Rules of the Game and This Kind of War.1 I would definitely second the recommendation for Rules of the Game if you're deeply interested in Jutland,2 interested in the broader RN of the era, or if you want to read an excellent work of military history that breaks down the details into the building blocks out of which armed forces are built.

1 He tells it mostly because he was the only other person present who had read both, which gave him an opportunity to be even more smug than usual. ⇑

2 This is the second book in the category of "work of genius on Jutland that definitely shouldn't be your first book on the topic". The other is John Campbell's Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting, although unlike that one, this one is readable as a book (instead of reference material). If you just want to read about Jutland, I'd recommend Nicholas Jellicoe's Jutland: The Unfinished Battle. ⇑

Comments

Funny how it was in today's mail... :-D

Does the work say anything about similar problems being shared with other navies of the period?

This book is now on my to-read list. From your description, it sounds a lot like Shattered Sword. The two books are also similar in that my library has audiobooks of both but not print copies. Oh well, it’s better than nothing.

@ike

Not really. The German officer corp is occasionally mentioned, but it's a book about British naval command. Drawing in other nations seriously would have made it even longer, and it's already very long.

@Grant

It's been a decade since I read Shattered Sword, but I can see the parallels. From memory, it's less mathematical (although Gordon does occasionally get into "I ran some numbers on ranges and the common values can't be right") and less about challenging a specific set of accepted views, largely because all of that work was already done.

Ooh, cool, I can be smug too

In a book about this battle, titled "The Battle of Jutland," there was related a brief exchange between two officers on the bridge of HMS Orion, the lead ship of four that formed the 2nd of 2 sub-groups that made up one of the battleship squadrons, occurring during the "night action," when for a time the German and British fleets steamed parallel to each other, and most of the British bridge officers were aware that those just barely visible ships were the enemy but were gripped by a strange paralysis wherein they could neither report these facts to Jellicoe nor act without a direct order from him and under these conditions a junior officer addressed the admiral, saying, "Sir, if you leave the line now and turn towards, your name will be as famous as Nelson's." And the admiral replied, "No, we must follow the next ahead."

Sometimes it's hard to see the opportunities in battle or in life, and sometimes one sees them but fears to act. Ironically, I know the name of the admiral who declined to make his name as famous as Nelson's (Leveson) though I don't know the name of the junior officer, but I always imagined that whoever he was--someone who as a senior officer played a significant role in World War 2? or who died not long after the battle in one of those little accidents that frequently occur in military settings? or who left the Navy after the war and lived the rest of his life as a private citizen, and this single sentence of rejected advice to an admiral was the only mark his existence left on "history," that, a century later, someone would read his words in the pages of a book--how fortunate he would be to know that he had the stuff to see the opportunity and take it.

I finally read this, thanks to your recommendation.

One of the features that struck me was: Beatty seems to have been on the right side of the debate in terms of doctrine, but also seems to have made multiple unforced errors at Jutland, and to have been a scoundrel in his personal conduct. Jellicoe, in contrast, was championing a defective doctrine, but appears to have made all the correct decisions

in the heat of battle' given the information available to him at the time, and also to have been unimpeachable in his personal conduct. Makes it much harder to assign a clearvillain' (plus of course, the bit where Jutland was after all a strategic victory).A second feature: I've heard it said (possibly by Devereaux?) that

societies produce militaries in their image.' And Victorian Britian producing a rigidly authoritarian navy would seem to fit. And yet, it seems like George Tryon might well have wrenched the navy onto a sounder doctrinal course, had he not made his fatal mistake (and had Markham not obeyed an obviously suicidal order). Evidence for agreat man' theory of history, or at least of organizational culture?Finally, of course, for all its authoritarian predilections, Victorian Britain almost surely practiced far less centralized command and control than modern societies. To what extent the pathologies of the 1916 RN are shared by e.g. the 2024 USN is a matter about which one cannot help but wonder.

Current USN vs RN pre-WW1:

ended the last global naval war, almost a century ago, as undisputed top dog

weapons & tactics completely transformed since then, but nobody has any significant experience of actually fighting with the new kit. Except ...

one sizeable conflict between smaller powers, a few decades prior, from which lessons learned may or may not still be relevant

a decades long rivalry with a near-peer competitor with a strong interest in asymmetric approaches, which never came to actual shooting

... followed by the sudden and rapid rise of a different peer competitor, genrally assumed to be the next opponent

@Humphrey

Re structure, I believe I also heard that line from Deveraux, and I think the point was more that you see this structurally. If there are sharp ethnic distinctions, you are likely to see those in the military. (This is true everywhere from the Hellenic kingdoms to the US until 1948.) A very strong aristocracy has historically meant a focus on cavalry, because it's a lot easier to look fabulous on a horse. The obvious modern example is the officer/enlisted split, which dates back to the days when the officers (particularly in the Army) were from the actual aristocracy. But it's hard to read the modern requirement that officers have a college degree as anything other than basically a class thing. I think this is probably true to some degree in tactics, but maybe not to the same extent. And I don't know how much Tryon could have changed things in the long term.

I would be a bit careful in drawing very straight lines between the RN back then and the USN today. There's an excellent book waiting to be written about the basic change in mentality in at least leading militaries from the start of the 20th century to today. (No, I don't think this is a book I am likely to write, sorry.) It's the sort of thing you notice when you are reading deeply on the RN of that era, where you would routinely have quite experienced officers making a category of mistake you only find in the media and the dumber congresscritters today. I don't think it showed up too much in Rules, but I remember there being some interesting passages in Marder's first volume about how a lot of the senior RN leadership basically didn't understand strategy. The usual reference for the start of the new school was the Fleet Problems and heavy emphasis on wargaming that came out of the Naval War College. And I think that continues today. It's worth noting that the Jeune Ecole in the USN has won several prominent battles in the last quarter-century, first with the LCS and then with DMO.

@Alan

The obvious big difference is that we have a lot more combat experience than they did. We may not have been doing proper ship vs ship naval combat, but as warfare has become more integrated, the boundaries between categories have broken down in ways that they hadn't back then. IIRC, none of the ships of the Grand Fleet had fired a shot in anger before the outbreak of WWI. This is very much not true of the USN today.

@bean The RN may not have fired a shot in anger before WW1`, but the redcoats certainly had. Indeed, I recall reading (possibly in The Guns of August) that the British Army was also admired pre-WWI, and its extensive experience of colonial brushfire wars was held to have imbued it with a high level of strategic competence and operational efficiency. And yet, it's actual performance in peer conflict, whether at the Somme or Ypres or Gallipolli, does not seem to have particularly covered it in glory. Analogously, it is at least conceivable that experience in brushfire naval confrontations is no training at all for peer conflict.

That said, I would indeed hope that the 2024 USN is not making the same mistakes as the 1904 RN. That's what `learning from history' is for. The question is whether it is making new (and perhaps equally serious) mistakes, which won't become apparent until something analogous to Jutland.

It's not particularly controversial that the British Army was the best in the world man-for-man in 1914. At Mons, the Germans mistook infantry units for machine guns, because of how good they were. But it had only six divisions in Belgium during the opening campaigns, and those men got chewed up badly. (I suspect that they were figuring out the same doctrinal issues everyone else was during the opening months of the war, and so weren't used particularly well, too.) By the time of the Somme, it was an entirely different army. Gallipoli was another case where issues with employment rather outweighed individual troop quality.

I see the point, but think this doesn't hold up to detailed examination. "Whatever happens/we have got/the Maxim gun/and they do not", but the Houthis have a lot of anti-ship missiles, if not the highest-end kit, and the Iranian ballistic missiles are really not that different from what we'd expect China to use.

Right, but the Houthis presumably don't have anti-satellite weapons, or the ability to electronically jam communications, or even missiles in sufficient numbers as to saturate sensors and communications.

Rules of the Game, in its last chapter, does seem to suggest that the USN (and RN) circa 1980 had grown quite profligate with (and dependent on) detailed signalling. But half a century has gone by and who knows if this is still the case.

In the past few weeks the Iranians have launched two large scale attacks on Israel, the first seemingly mostly drones, the second with over a hundred ballistic missiles. I would guess that the defensive system was mostly US and Israel with only a few allied contributions, but definitely involving a network of radar systems and missile batteries.

Still not a full scale peer on peer conflict, but a big step up from the Houthis.

On centralized command and control, I wonder if the modern Russian and Chinese militaries would actually be worse off in the face of massive comms jamming and satellite denial than their western counterparts.

Western militaries mostly do retain a tradition of independent decision making at the lowest levels. At least, that's my inexpert view from outside - I wouldn't know if micromanagement from on high has become so commonplace that independent thought is no longer practised by anyone below the level of General / Admiral.

The Soviet tradition which is carried on by the modern Russian and Chinese is for top down control. Anecdotally the Russians are losing a lot of generals in Ukraine because when anything goes wrong, a very senior person has to go to the front and physically shout at people to get them to do something different.

If initiative and local decision making remains important in naval warfare, an adversary knocking down western satellite networks might actually be doing us a favour.

@Hugh Fisher

That's certainly possible, perhaps even probable. And analogously, Scheer seems to have made more than his fair share on unforced errors at Jutland (which was, in the final analysis, a British victory, notwithstanding the problems with RN doctrine, ammunition handling practices, etc).

But `satellites and communications networks go down, USN does poorly, PLAN does disastrously' could easily net out to a kind of underwhelming victory...like Jutland.

Yeah, the Iranian attack pretty much took the last one off the table. You're not wrong on the other two, but ASATs that can reach GEO comsats are rare.

I certainly don't think it's gotten better, although the way we run that kind of stuff these days is very different than the Victorian RN, and I think we'd handle it better than they did at Jutland. Mission Command is a big thing, and our ships spend a fair bit of time operating independently.

(The other aspect is just that there's a lot more interest in dealing with communications issues because there's also a lot more interest in deliberately causing them. It's hard to have a substantial jamming plan without having a plan for what to do to deal with enemy jamming, whereas there was nobody who had a deliberate brief for causing smoke problems or blowing away signal halyards.)