So far, I've covered the process by which a battleship gets from the drawing board to the fleet. But it wasn't always smooth sailing. For various reasons, a battleship might not ever enter service, or it might enter service in a form entirely different from the original design. It's worth taking a look at why this happened and what happened to these unlucky ships.

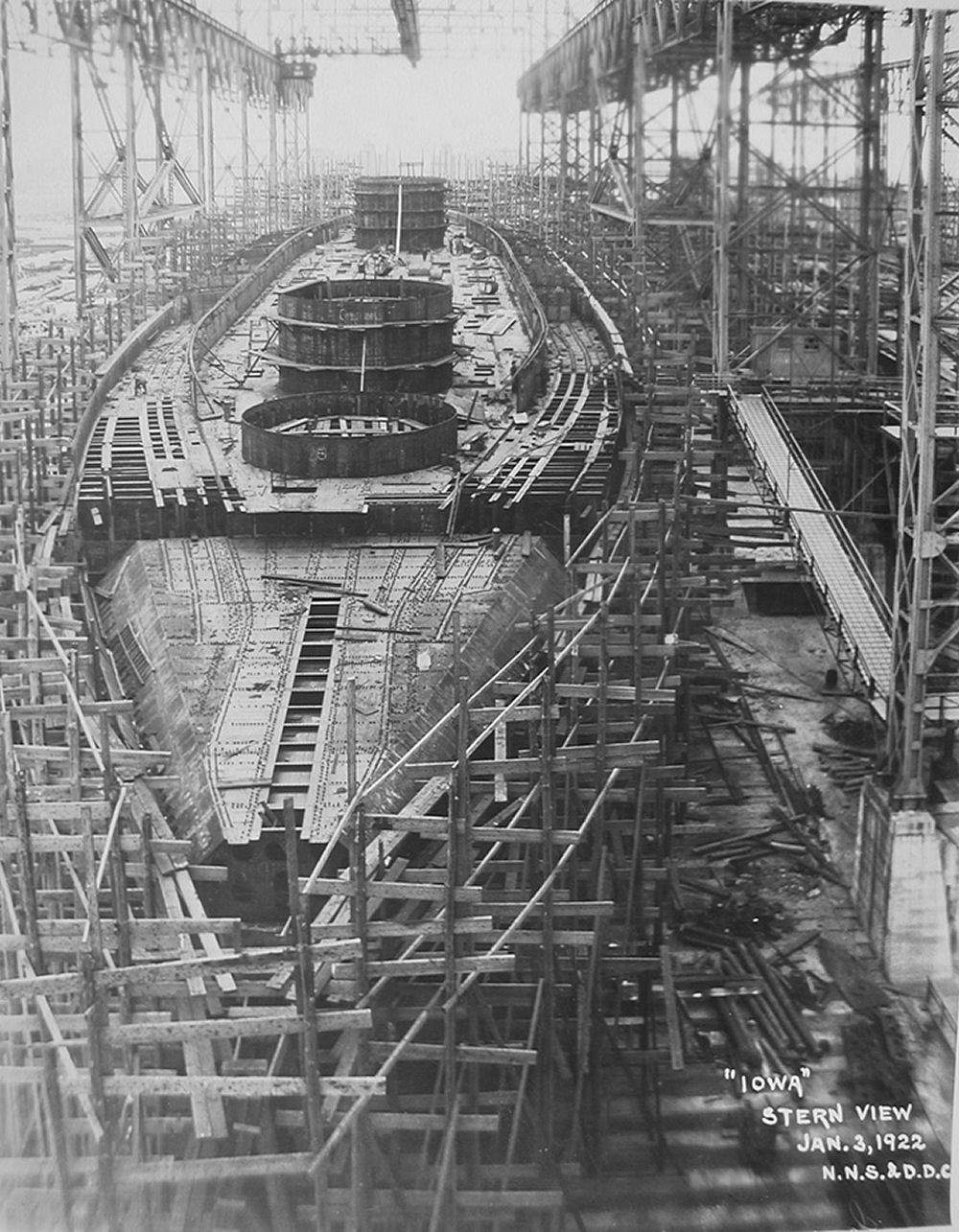

USS Iowa (BB-53), a battleship that was never completed

Almost all of these cases stem from one of the world wars.1 Battleships, extremely expensive and relatively slow to build, tended to be sacrificed for other vessels in the press of wartime needs. Every single battleship that fought during WWII was laid down before its nation entered the war. During WWI, the British managed to complete a handful of battlecruisers, but even this was a major drop in capital ship production relative to their output before the war, and nobody else managed to do the same.2 Even a number of ships laid down before the war were suspended for the duration and subsequently cancelled. After the war, a new naval race between the US, Japan and Britain seemed to be brewing, before being averted by the Washington Naval Treaty. This allowed each country a small number of new ships, but most of the American and Japanese building programs would never see service.

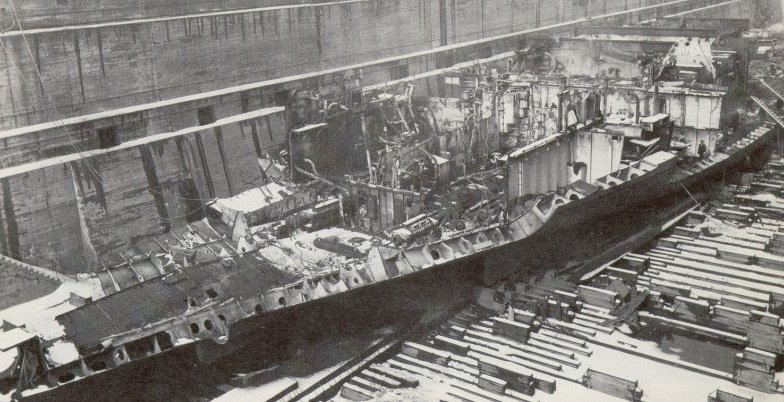

USS Delaware being broken up, 19253

The standard fate for unnecessary ships was being broken up. A battleship, after all, is a large chunk of high-quality steel, and there's little point keeping it around if you aren't planning to use it.4 Steel that hadn't yet been assembled was often redirected to other ships or kept in storage, but if it had been prepared and installed, it would generally have to be melted down for reuse. But scrapping was a last resort, as it involved throwing away a lot of work, and navies tended to wait until they were sure they wouldn't actually use the vessel before scrapping it. Battleships suspended during wartime generally weren't scrapped until after the war, when it was clear that the ship wasn't worth completing due to changing weapons and economics.

But a few ships found other purposes than feeding a steelworks, at least for a while. A surprising number were completed as aircraft carriers, mostly in the 1920s, and a few of that vintage were used to evaluate how a battleship would stand up to attack. And then there were a bare handful that lingered incomplete for years, as navies searched for a new use for them in a changing world.

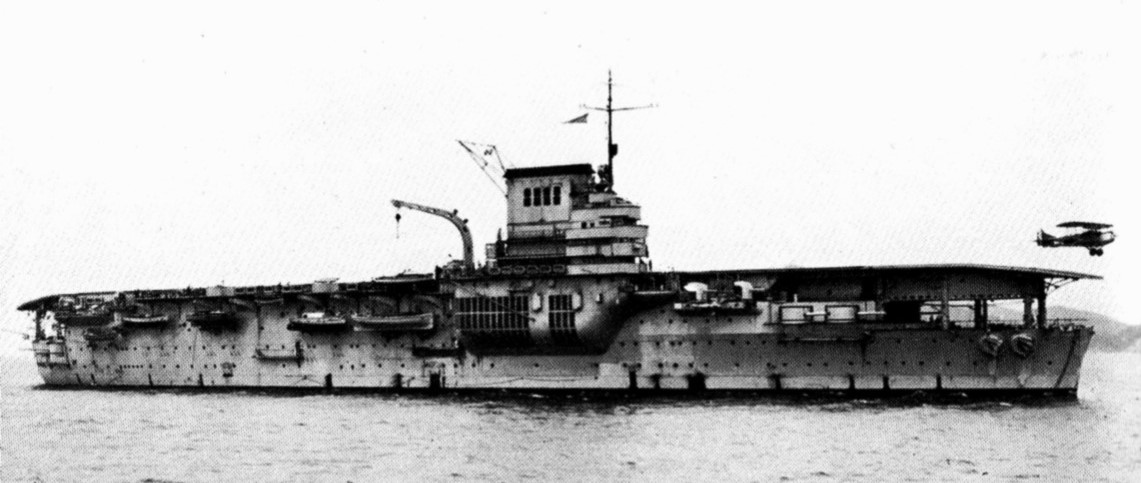

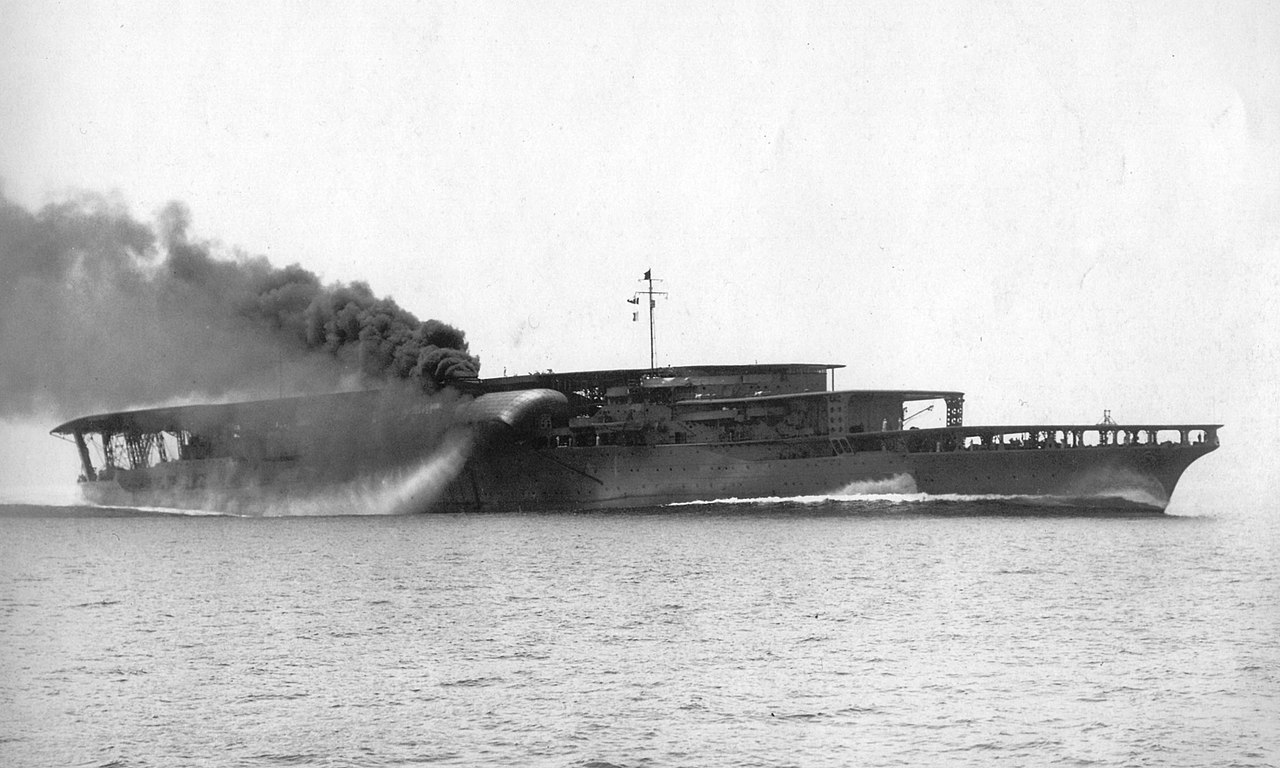

Eagle

The first battleship completed as something else was one of the products of the South American Dreadnought Race. In 1911, Chile had ordered a dreadnought from British shipbuilder Armstrong, with an option for a second ship. That option was exercised in 1913, but the outbreak of war saw neither ship completed yet. The first vessel was almost finished, and she was bought by the British as HMS Canada and completed in 1915. The second ship, to be named Almirante Cochrane, was structurally largely finished, but hadn't had her armor installed yet. She remained in limbo until early 1918, when the British bought the incomplete ship from Chile for conversion into a carrier under the name Eagle. Her completion was delayed until 1920 by the need to incorporate lessons from trials aboard HMS Argus and HMS Furious, and the result was a ship that looks a lot like a modern aircraft carrier. Most notably, she was the first carrier to be completed with the starboard-side island that is ubiquitous today, and proved a much better solution to dealing with the exhaust gasses than was possible in a flush-deck carrier. Eagle gave valuable service as an experimental carrier in the 1920s, although by the outbreak of WWII, she was too slow and too small to be capable of first-line service. She spent the first months the war in the Far East and Indian Ocean, hunting German commerce raiders, but then was drawn into the expanding war in the Mediterranean, where she was sunk by a U-boat in 1942.

Bearn

But Eagle was just the first of seven battleships and battlecruisers that were converted to carriers while under construction.5 The first was Bearn, a unit of the French Normandie class. Unlike her sisters,6 she was far from launch at the outbreak of war, and in 1920, was fitted with an improvised flight deck for carrier trials. These went well enough that the French converted her into a proper carrier, their only such vessel until after WWII. By 1939, she was old and slow enough to make her suitable only for second-line tasks, and she found herself carrying gold to the US to pay for weapons when France fell in 1940. She spent most of the rest of the war essentially interned in Martinique, as the Vichy French and Americans both tried to keep her from joining the other side. Eventually, the Free French became dominant, and she was converted to an aircraft transport just in time for the end of the war. Postwar, she supported French operations to reestablish control of Indochina, before being turned into a barracks, finally being broken up in 1967.

Lexington and Saratoga in 1933

The next four ships were the direct result of the Washington Naval Treaty, which found both the US and Japan with extensive building programs. One article of the treaty allowed each power to convert up to two ships under construction to carriers instead of scrapping them. Both nations chose pairs of battlecruisers, the Americans Lexington and Saratoga and the Japanese Akagi and Amagi. All four were big, fast ships, and proved to be very successful as carriers. In fact, they were so big that the Washington Treaty limit of 27,000 tons on carriers was raised to 33,000 tons for conversions. The Lexingtons proved to be superb carriers, capable of 33 kts and with flight decks that wouldn't be surpassed in size until 1945. The only downside was that they were so big even the raised treaty limit wasn't enough and the Americans took advantage of a clause that allowed 3,000 tons to be added for protection against air and submarine attack on their new-build ships. Lexington was lost at Coral Sea, but Saratoga survived the war and was expended as a target at Bikini.

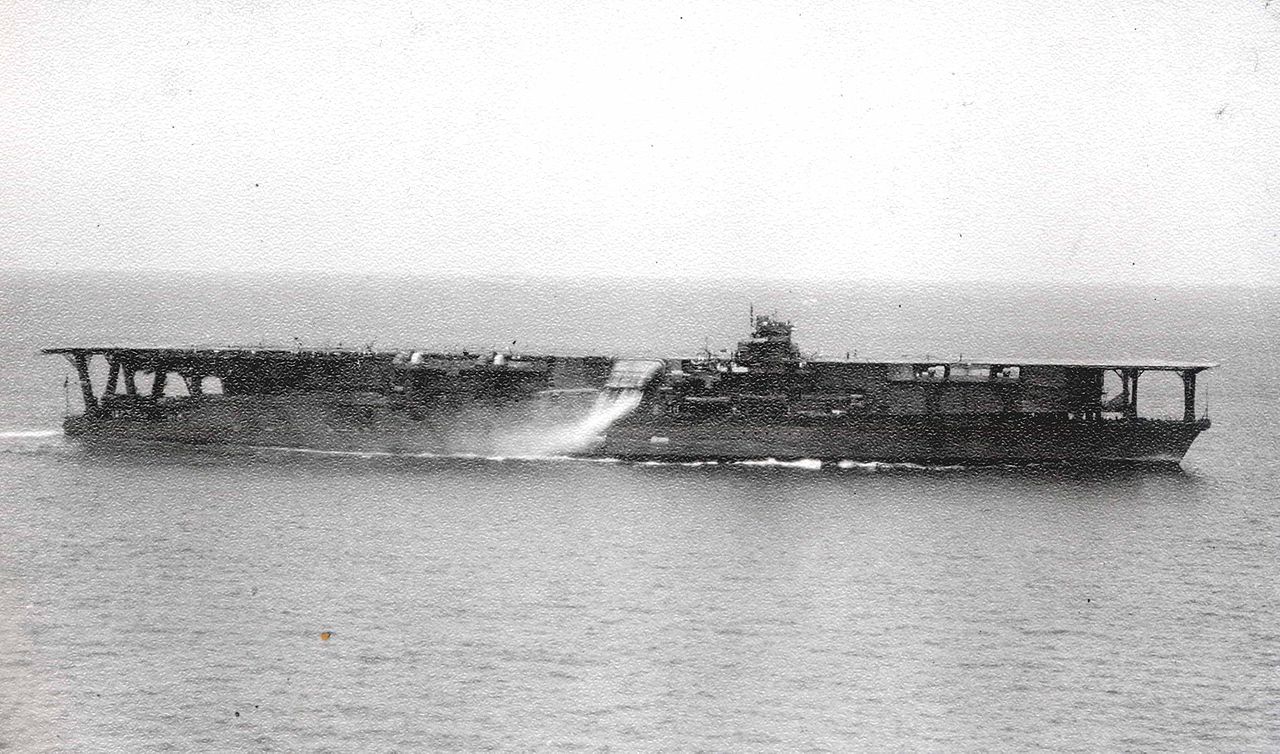

Akagi early in her career with three flying-off decks

The Japanese had a slightly harder time of it. While still being converted, Amagi's hull was damaged by an earthquake in 1923, and she was replaced by the battleship Kaga, previously slated for scrapping under the treaty. Kaga was still quite fast, capable of 28 kts, and she and Akagi both participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor and other operations throughout the opening months of the Pacific war before being sunk at Midway.

Kaga after a major refit before WWII

The last Japanese carrier conversion was the direct result of that battle, although it was less successful. Shinano was laid down as the third unit of the Yamato class, but in 1942, the Japanese decided to convert her into a carrier. For some reason, they chose to make her a support carrier, with repair facilities and replacement aircraft for other carriers, instead of a front-line fleet carrier. In any event, they weren't able to get much use out of her. In November 1944, only a month after her launch, she was torpedoed while in transit by the submarine Archerfish. Many of her watertight doors had yet to be installed, and the crew's efforts to save her were unsuccessful. She remains the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine in combat.

One of only two photographs of Shinano

Of course, the idea of turning a battleship into a carrier during wartime was hardly unique to Japan. Britain looked at turning Vanguard into a carrier, and the Americans investigated carrier conversions of the Alaskas and Illinois and Kentucky, the last two Iowas. All of these foundered on the fact that the resulting carriers would have cost nearly as much as a new-build carrier and wouldn't have been nearly as good. Some of these ships were finished as battleships, while others were considered for weirder roles. We'll pick up the story there next time.

1 The only exception I'm aware of is the Stalingrad class battlecruisers, started after WWII by the Soviets because Stalin didn't understand sea power. They were cancelled after his death. ⇑

2 Technically, this isn't quite true. The Japanese built the Ise class battleships entirely during the war, but while they were a combatant, their contribution was extremely limited, and it seems fair to ignore this particular outlier. ⇑

3 Delaware was an early US dreadnought, but I couldn't find any pictures of the ships cancelled under the treaty actually being broken up. ⇑

4 Unless, of course, you're going to turn it into a museum, but that's unlikely for a ship that you didn't finish. ⇑

5 Honorable mention goes to Courageous and Glorious, who were completed as battlecruisers and converted to carriers later, and Furious, completed with a flying-off deck forward and an 18" gun aft. ⇑

6 All of which were launched by 1915 and subsequently scrapped after the war. ⇑

Comments

Could they have potentially had them sooner, even if it wouldn't save any money and result in an inferior carrier?

Because that's the only scenario in which it'd make sense (but probably not before the end of the war so it'd end up a waste anyway).

I think it would have been a little bit sooner, but they were in a spot where the time advantage wasn't enough to actually justify it. Both the US and Britain had major fleet carrier programs going, and the converted battleships would have been relatively minor additions to fleet strength when they entered service in 1945. So you're paying more for a worse carrier at a time when you already have plenty of carriers.

WWIIafterWWII had a pretty good post about Bearn.

Semi-related: the Ukrainian cruiser Ukrayina

For peacetime cancellations/pauses while they figured out what to do, I'm sure this was less of an issue, but how did this impact drydock/overall production capacity during the war? WWI and WWII era slips seem less specialized than what exists today, but even so there can't have been that many building slips available, especially once you factor in the cranes and supporting infrastructure.

Or was all of that fungible enough that there was not a large opportunity cost of basically abandoning a ship on the ways while diverting personnel and resources to building destroyers and subs or whatever.

On further consideration WWI/WWII subs and frigates are probably small enough/numerous enough that a single slip wouldn't really hit their production very hard, but for cruisers and other large ships, it seems like it would be more of a constraint.

I looked into this some, and it seems to have come up less than you'd expect. The only case I know of where an incomplete battleship was moved to free a slipway was Kentucky. The Lions were broken up on the slip during the war, but all of my sources agree that this was primarily because the design was going to be updated if they were completed, and not because they specifically wanted the slips for something else. Dulin and Garzke even says that the removal was done by May of 1945, two and a half years after the ships were cancelled. So they obviously weren't in that big of a hurry. The H class (2 laid down before the war) seem to have been largely the same, although details are unclear.

On the whole, I'd guess that slipways weren't generally the production bottleneck for big ships (cruisers and up), so having a couple of slipways occupied by partially-completed battleships wasn't seen as a big deal. It's also worth noting that the number of slips occupied by battleships generally fell during the war. The British, for instance, launched three KGVs in 1940 and didn't lay down the rest of the Lions like they'd planned to. That frees up several slots for carriers.

It’s also worth pointing out that battleships weren’t the only ship type that saw production hit hard by the outbreak of war. The British had exactly one carrier built entirely during the war (Indefatigable), and she was ordered in 1938. For that matter, they only finished 3 6″ cruisers during the war, along with 7 Didos (which were considerably smaller). The US was unique in getting a significant number of large ships that were built after it entered the war into service, an achievement made more impressive by the 2-year head start the British had.

Looking at the Essexes, 11 were ordered in 1940, all commissioned by 1944. 2 ordered December 1941, commissioned 44-45. 10 ordered in August 1942, 4 commissioned before the end of the war. The standouts in this group are Bon Homme Richard and Shangri-La, commissioned November and September of 1944 respectively. 2 more finished later in 1945, 2 in 1946, 1 in 1950 and 1 was cancelled. The last 3 were ordered in June 1943. 1 was cancelled and 2 completed in 1946. Eyeballing the data, most of the spread in completion time seems to be related to when the ships were laid down, although that doesn’t make it certain that slipways were the bottleneck.

@bean

You also had HMS Colossus commissioned in december '44, and a bunch of her sisters in '45, plus the minotaur class cruisers. But I think a lot of that is an artifact of the british handing the pacific war to the US. the brits didn't really need a lot more fleet carriers, battleships, and cruisers to fight germany and italy, and those enemies were a much bigger priority than japan. that didn't change until the US was involved and the brits were pretty happy to turn the pacific war over to us.

I did miss the light fleets, but in fairness, those were deliberately small and austere, and deserve to be compared to the Independence class, not the Essexes. And I didn't miss the Minotaurs. Swiftsure was one of the 3 CLs I counted, along with Bermuda and Newfoundland.

On the subject of building battleships at the end of WW2:

IF a couple of naval battles had gone differently (say some carriers getting destroyed by 16/18 inch shells in heavy weather during which planes couldn't operate), one could imagine that people would still want new BBs in say the 1950s or 60s.

So... what would they have looked like?

I'm going to guess that nuclear power would be an option. But what else?

I don't think they would have lasted much longer than they actually did. By the mid-50s, you had nuclear-tipped SAMs and all-weather aircraft, which basically kills the case for the battleship. There's more on this in The Battleship and the Carrier.

What about an alternate history in which aircraft advanced at a much slower rate but all other technology was basically the same?

I don't know HOW aircraft development could have proceeded at a much slower rate than it did historically, though - the field was full of low-hanging fruit and the bad ideas usually killed their proponents pretty quickly. And up until WWII, a lot of the powerplant engineering was able to leverage the developments in automotive engineering for a large user base.

For aircraft to develop at a slower pace, I think one or two things would have to happen.

No world wars. Obviously this would affect everything so you can't get a "but everything else is the same".

Tetraethyl lead is never discovered or it poisons someone in the lab right away so they drop it as too dangerous before it becomes an industrial necessity. Without cheap high octane petrol the development of high performance aircraft is much slower, and might need to wait on jet engines before getting anywhere.

Or the public health people who thought it was a stupid idea manage to win out. OTOH it only takes one power to decide that increased crime and reduced population IQ is a price worth paying for more powerful aircraft engines and everyone would be forced to use it. Not having high octane petrol would also make diesel engines look a lot better so until the gas turbine aircraft might just have diesels.

Thinking about what kept battleships from being completely obsolete it was that it took a while for aircraft carrier operations to become all-weather and I suspect it was that and not so much the performance of the aircraft that really mattered. That probably would require no wars and maybe even that wouldn't be enough and they'd need to be an arms control treaty severely restricting aviation and even there you might have to hurt civil aviation to do it (airship fans may not mind).

But my question really should just ignore all that.

I thought naturally-aspirated diesels didn't have the power to weight ratio to run heavier-than-air aircraft?

But, yeah, I suppose taking tetraethyl lead off the table would particularly impact aircraft, and that the other side effects are less noticeable, though making gasoline engines relatively less powerful probably has some effects on ground combat in WWII - given that the M4 Sherman was gasoline-powered, and the relatively-extreme mechanisation of the US Army.

Billy Mitchell can't run his rigged demo without the B-17, either...

The B-17 was almost 20 years off when Billy Mitchell was showboating with Ostfriesland. As for diesels, I believe most of them were supercharged. The Junkers Jumo 205 definitely was, and it was IIRC the most widely-used aircraft diesel in that era.

Also, there were diesel-powered Shermans. They just mostly went to the Russians instead of the US.

Early aircraft pioneers not named "Wilbur" or "Orville" seem to have had a blind spot where three-axis flight control was concerned. They'd have figured it out eventually, but e.g. a fatal crash at Kitty Hawk might have set things back just enough for airplanes to still be impractical toys in 1914 and all of that war's aeronautical inventiveness to have been focused on better Zeppelins.

I think by 1939, though, the airplanes would still have overtaken them and then reached about their current level in the 1950s. In particular, the tools for all-weather vs clear day only flying develop independently of whether you're using aerodynamic or buoyant lift. Even if the rest of the aircraft were 1930s-equivalent, an all-weather Kate or Swordfish really hurts the case for battleships as a hedge against carriers for 24/7 operations.

This isn't really true. You can fly an airship at night, but one of the things that killed them off was the fact that they're terrible at coping with weather. For instance, the German naval zeppelin force was only able to patrol maybe one day in three throughout the war, primarily due to bad weather. The only patrol aircraft in WWII which had that kind of availability were in the Aleutians, which make the North Sea look like the Caribbean.

Ian Argent:

They do, just that basically everyone stopped making high performance naturally aspirated aircraft engines.

As far as I can tell the Packard DR-980 was naturally-aspirated.

bean:

Also a two stroke.

@Ian Argent

John might have beaten me to the punch but one of the issues with early aircraft is that people with good ideas were killed off almost as quickly as those with bad, and most pioneers had both in abundance. A run of bad luck and key ideas could be discarded as "too dangerous" or "unworkable."

I am enlightened. And, of course, by WWII aircraft engines were having their aspirations mechanically enhanced anyway. And it's not like diesels can't be mechanically boosted.

A quick google search says the Heer used petrol for their tanks as well, so no high-performance gas engines hits both sides on the Western Front. It might have an effect on the Eastern Front, though.

Without high-performance petrol engines, does the gas turbine engine get crammed into land vehicles more regularly instead of being a curiosity? (Looks like there were some gas turbine-powered locomotives as early as '39-'41 - and Union Pacific ran several locomotives that burned Bunker C up until 1969; when Bunker C became uneconomical)

If I was capable of writing stories instead of getting bogged down in world-building, I'm tempted to write about a world where, without tetraethyl lead, diesel is the "high power to weight ratio" option and steam is the low one, justifying STEAMPUNK! (Ahem)

But only 2 strokes must be.

A single prototype.

Diesel would eventually replace steam for basically everything but electricity generation, just as it did in our world.

Oh, sure, be that way!

And given the evolution of naval power plants (where gasoline was never a serious option until relatively recently), it probably wouldn't take any less time.

The reason I brought up the gas turbine in a world without tetraethyl lead in use was perhaps they get developed earlier? I don't really know what the reason they didn't get developed until WWII was

@Ian,

If you want to world build where steam stays in-contention-with/ ahead-of internal combustion engines: just make oil a lot rarer than it actually is.

If oil is a geological curiosity, and coal is still in mass abundance, then steam remains king. I suspect that the option of coal-to-liquid conversion, and using powdered coal in internal combustion engines (piston and gas-turbine) are still physically feasible, but would be enormously delayed if those engine types were not developed to a high degree without cheap liquid fuel in the first place.

What this does to geopolitics when the oilfields are no longer a factor is left as an exercise for the

readerwriter.Ian Argent:

The WWII PT boats were petrol powered and petrol-electric predated diesel-electric for submersible surface vessels.

Ian Argent:

It just took a while for the necessary alloys to be found and for all the other problems to be solved.

Doctorpat:

You're going to need coal to be in abundance otherwise there won't even be steam-engines but I suspect that knocking out coal is geologically easier than knocking out oil.

Knocking out oil while keeping coal might also make nuclear marine propulsion more attractive when they finally figure that out.

Sniff. Mere boats. Next you'll be trying to claim that 8" guns are "big guns." ;)

(I didn't forget them, but seriously didn't think they needed to be mentioned)

As far as I know, gasoline isn't a serious option for large vessels, and never has been, unless you're planning on running a gas turbine on it. Diesel is where the vast majority of the work for large engines has been, and I think there are scaling factors that make it work better. Not to mention the fire hazard, which killed it on submarines. I have posts on this coming up, and while my library on this is a bit dated, I think I would have run across if someone was using gasoline.