I recently ran across a reference to Mikasa as the fourth unit of the Shikishima class. This was interesting, because every reference I've seen to Mikasa has her as the sole unit of her class. But then I started looking, and in the process, ended up wondering about why we draw the lines where we do.

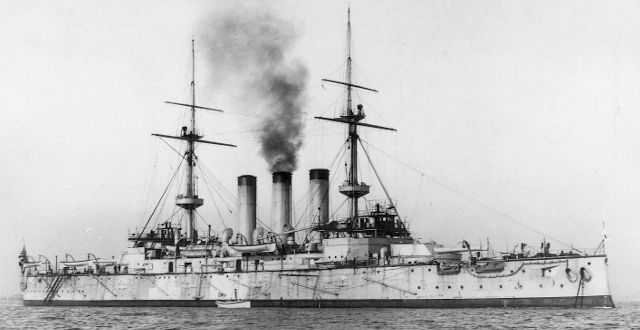

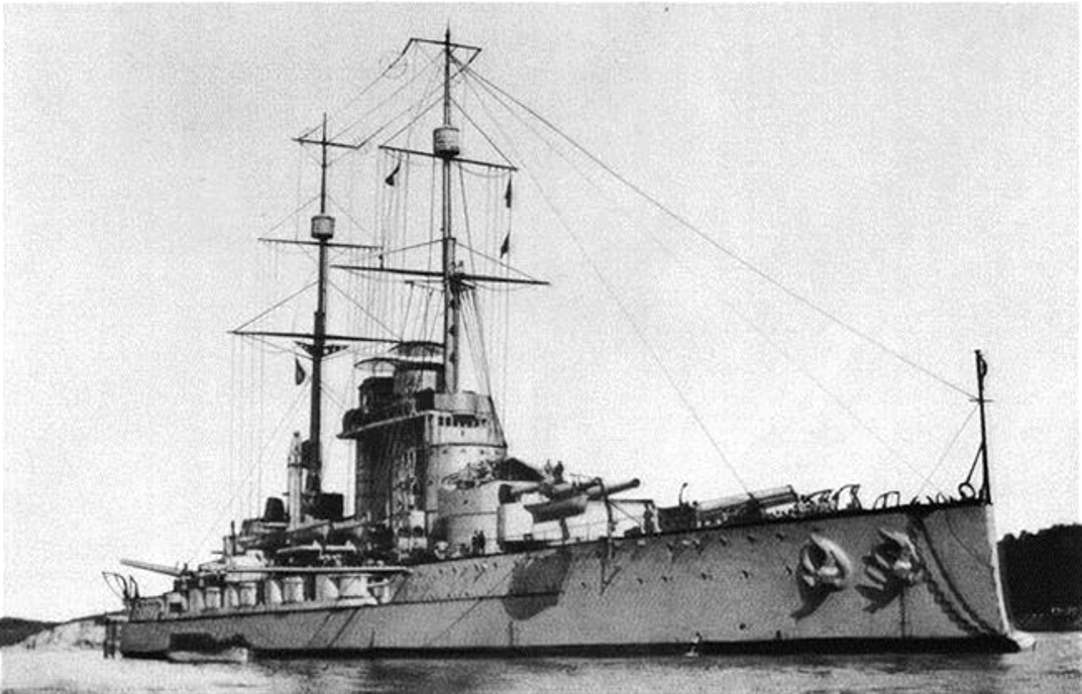

Shikishima

In the years after the Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese government spent a lot of the indemnity they'd extorted from the Chinese on battleships, buying four from British yards. In most sources I'm aware of, the first two, Shikishima and Hatsuse, are treated as being sisters, while Asahi and Mikasa are singletons. But all four ships have the same basic specifications, a displacement of around 15,000 tons, speed of 18 kts, armament of 4x12"/40 guns and 14 6", and a 9" belt. There are some minor differences in their exact dimensions, but on that front, Shikishima is more like Asahi than Hatsuse.

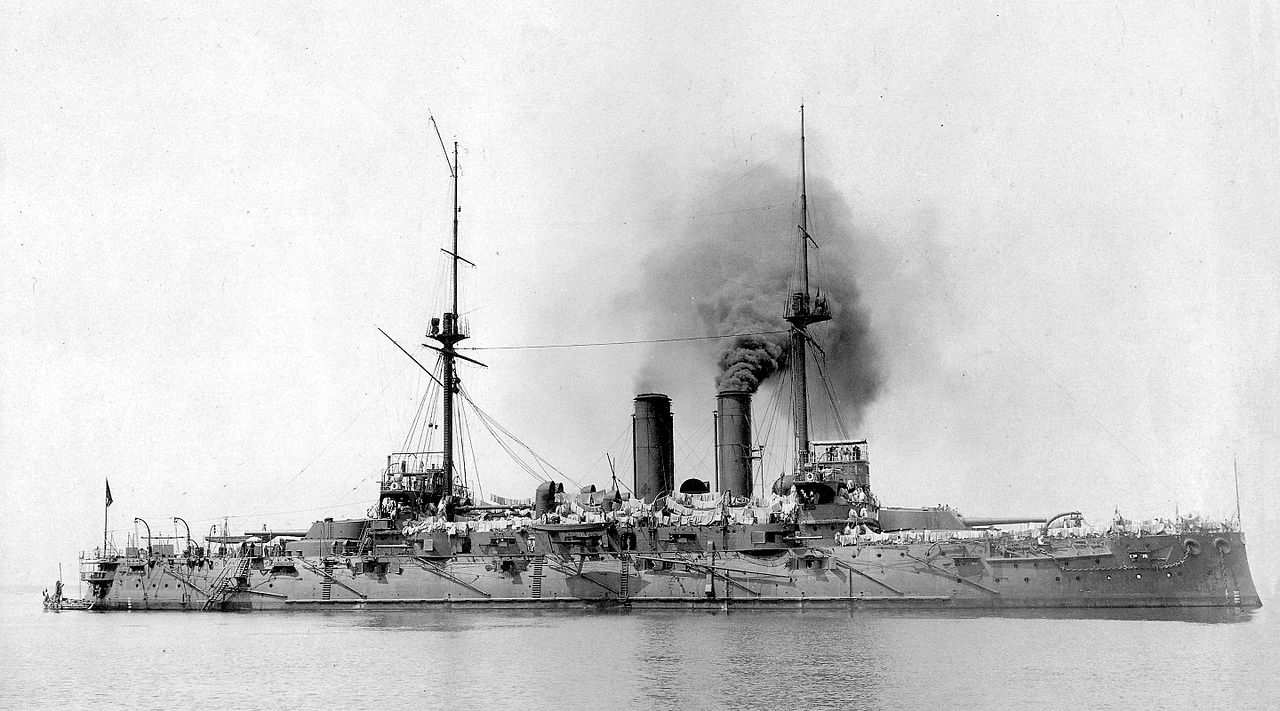

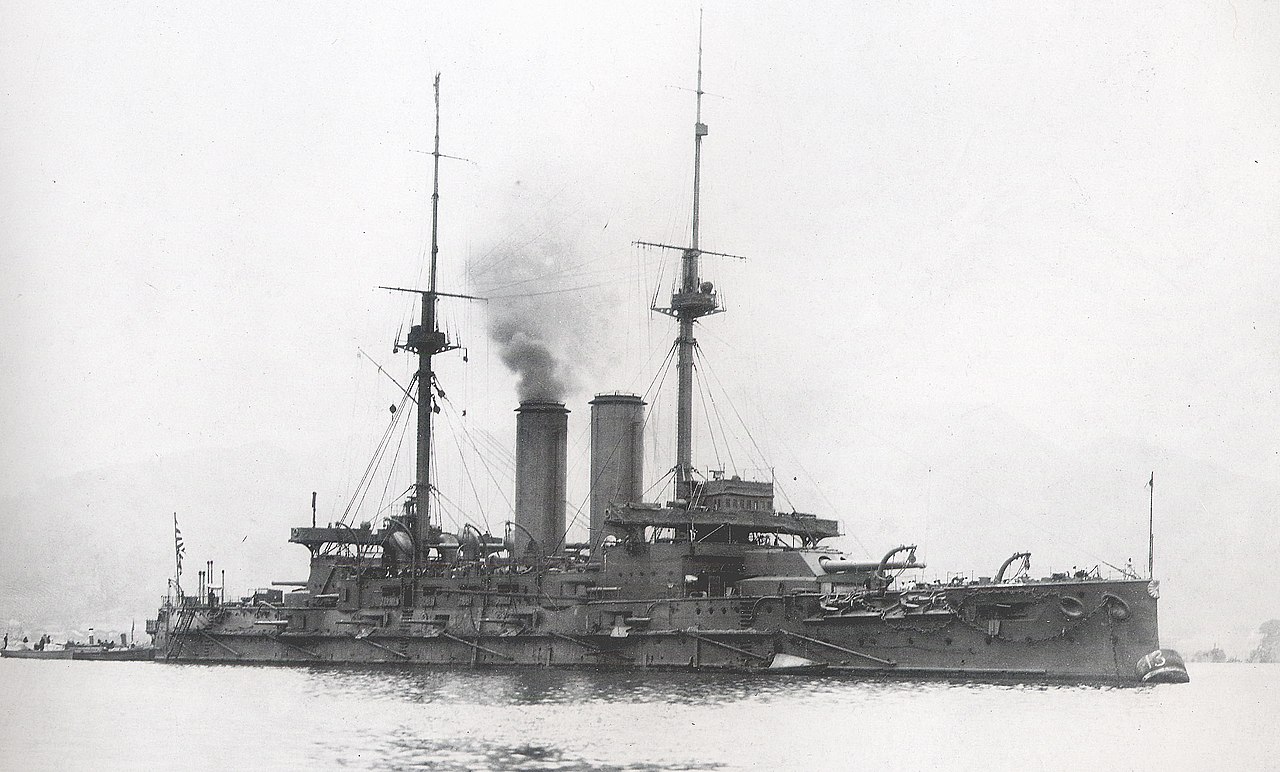

Now, none of this should be particularly surprising. All four ships were ordered from British yards under the 1896-1897 naval plan, and there was obvious desire to make them into a tactical unit. Asahi in particular was a near-clone of the first two ships, the only major difference being that she had two funnels instead of three, with some consequent changes to the machinery layout and improved watertight subdivision. Mikasa, laid down a year or so later, had more tweaks, including slightly improved loading systems for the main guns and a continuous belt to protect the 6" guns on the main deck instead of individual casemates. Several sources at the time appear to consider Asahi part of the Shikishima class, simply noting the difference in the funnels, while breaking Mikasa out, probably on the grounds of the different armor layout.

Asahi

But all of this raises the question: what is the point of this "class" concept? Obviously, it's an attempt to describe the world and simplify the complexity of having to understand each ship individually. And for ships built in countries that are fairly open about their process and internal classification, these tend to dominate all discussion. Obviously, the Nimitzs are all the same class because NavSea says so, while the Oregon Citys were different from the Baltimores because BuShips said that the rearrangement of the superstructure was enough to break class continuity (and the two funnels were trunked down to one) even though these changes were objectively less than those that occurred across the Nimitzs throughout their service.

Mikasa

And even for places which aren't so accommodating about publishing their records, there are some lines which are obvious, but the example of the Shikishimas points out that what gets counted in a class can be somewhat arbitrary, depending on who is doing the drawing and what they see as important. From the perspective of the fleet's commander, there was no real difference between the four ships, which could be safely treated as one class. This would also be true of most wargames and anyone who was doing grand strategy.

From a 1913 Brassey's Naval Annual. Hatsuse is absent because she was sunk almost a decade earlier.

An alternative is to simply split off Mikasa because of the different armor layout, and this appears to have been reasonably common in reference works at the time, as seen above. This works if you're interested in more technical details, and presumably also helps keep page count down, which was probably a lot more important back then, when these books were reasonably widely published, than it is today, when the major reference works tend to be specialist and expensive enough that the cost of extra paper can be ignored. Of course, this still leaves two ships that appear quite different lumped together, which brings problems for other users.

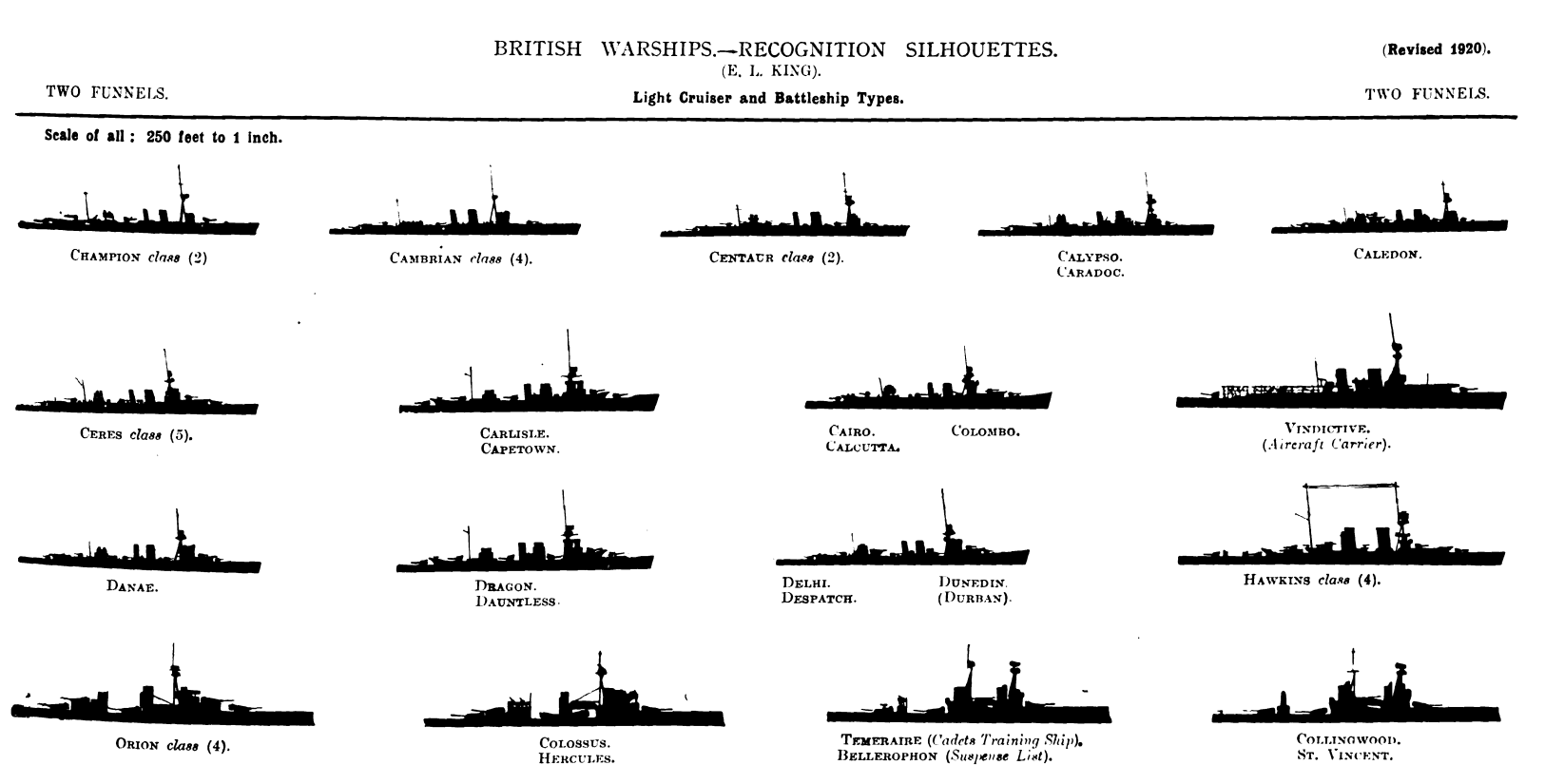

A ship recognition page from the 1920s Jane's Fighting Ships

Specifically, for many years one of the key uses of naval reference publications was visual identification of passing ships. In the days before AIS and ESM systems loaded with electronic signatures, finding an appropriate picture in Jane's might have been the only way to identify a passing warship, and as such, there would be incentive to split off Asahi from the other two ships, because she is visually quite distinctive. Later on, as this passed into history, modelers got involved, and for modeling reference, splitting up ships entirely by visual similarity is even more important, although these publications also go into great detail about the differences between ships of the same class.1

Szent Istvan

A couple of other examples are worth pointing out as well. The Austrian Tegetthoff class had one of the weirder histories, with three units built at Trieste and one at Fiume, with the Fiume-built unit, Szent Istvan, having two shafts instead of four in the rest of the class. This didn't seem to cause anyone to think that she might belong in a class by herself, and it's never more than a minor note in the propulsion/engineering section of any description of the class. A cynic might suggest this was because the effect was entirely below the waterline and didn't show up in photos, because from an engineering perspective, it's a bigger change than, say, the one from Baltimore to Oregon City.

HMS Spiteful of the B class

And then we come to British destroyers in the years before WWI. This was an era where a destroyer was still quite small and relatively cheap, and particularly before 1903 or so, it was standard practice for builders to design ships to loose Admiralty specifications. Things started to tighten up with the River class, but even this had several different sub-designs depending on builder, but never seems to have been considered to be a batch of different classes. Beyond that, the practice of allowing certain shipyards, most notably Thornycroft and Yarrow, to design and build "Specials" intended to be a knot or two faster than the Admiralty design persisted through the outbreak of WWI, and machinery design was largely left up to the yards even in "standard" ships. And yet, for the sake of sanity, the Specials were generally considered to be of the same class as their Admiralty counterparts, at least so long as only a few were built. In 1913, the Admiralty decided to completely paper over all of the cracks in the system, lumping all of the pre-Rivers into one of four classes. The 27-kt (design) ships became the A class, while B, C and D classes were all 30-kt ships distinguished entirely by having four, three or two funnels respectively. It's not entirely clear why funnels were chosen as the distinguishing feature here, but I'd guess it might have been because ships with similar machinery would have the same number of funnels, so there was at least some attempt at commonality when dividing up almost 120 ships.

These are definitely the same class

So what do we make of all this? To a large extent, class is a construct, intended to make understanding and thinking about ships easier, and there are multiple ways to categorize ships without any one of them being specifically wrong. Sometimes this is just based on what you care about, as with the Shikishimas that started this whole thing. If you're a modeler, there are two units, and the other two ships are singletons. If you're a ship analyst, then there are three and Mikasa stands alone. And if you're an admiral, then there's four. Which scheme makes it into a reference book depends on what the book's author cares about, and what previous books have said. And then occasionally you run into a T-shirt in Mikasa's gift shop that shows a glimpse of an alternate way of thinking about this...

1 Usually. At the same time, I have seen a lot of "Iowa" models with a quad 40 on top of Turret 2, although almost always from the lower end of the realism spectrum. ⇑

Comments

Class also aligns to logistical complexity, though probably not to the same extent as with aircraft or ground vehicles - how many different varieties of spare propeller shafts and reducing gears does the Navy have to procure, etc.

You are over-looking the politics here. Fiume is in Hungary; Trieste is in Austria proper. Saint Steven (Istvan) is the patron saint of Hungary (her first Christian king). "We would like Hungarian suport for this naval spending bill and are willing to build a quarter of the class in Hungary." is sort of the point.

@redRover

I think standardization of such things became more important as ships got more complex. When everything is made out of wood, then you don't really have to care. Metal is a bit harder, but that sort of stuff was generally fabricated at need.

@ike

Splitting classes across different yards is very, very normal. The weird bit is the different machinery, which I can't fully explain in terms of Austro-Hungarian politics. (I did actually suspect that was the reason for the split, but didn't want to confirm and it was beside the point.)

Trieste was a much larger city than Fiume (~x4) and its industry more advanced.

Form memory, the yard in Fiume was slightly too narrow to build an unmodified Tegetthoff.

It's not quite that. I found an article in Warship International which indicates that the reason was that, yes, Szent Istvan was the Hungarian ship, and was obliged to use as much Hungarian material as possible. Which included machinery, because there was a machinery builder in Budapest. Said machinery builder had different licenses than the ones used by the yard in Trieste, so the ships ended up with very different plants. It wasn't unknown for, say, British ships to have different builders and I think even fairly different designs (Parsons vs Curtis turbines, for instance) but the shafting thing is unique, AFAIK.

Which of the british ships of the 1890s would come closest to the Mikasa in design?

That's amazing!

I guess procurement weirdness is universal

@timshatz

The Formidable class were more or less the basis for the design of all four of the Japanese ships ordered in 1896.

Thanks bean, appreciate the info.

All of this explains why the Arleigh Burke class is considered one class instead of two, three or even four, as might make sense. The same seems to have been true of the Ticos, though I do find occasional references to the "Bunker Hill-class".

Personally I'd have been inclined to draw a line between the units with a hangar and those without, since that does make some difference in how they can be employed. Of course, I'd also tag 79 onward as CGs instead, so, y'know, go figure.

@Jade: (public) official class definitions are presumably influenced by whether it's politically easier to do an 'upgrade' or a 'new design', i.e. Burkes are still Burkes (and Virginias are staying Virginias despite ~doubling their missile capacity) because asking for a new class might get you a Zumwalt.