There's a criticism of the USN's strength that I've heard several times. It's based around the idea that in 1900, Britain could control the seas with a navy twice the size of the next two largest fleets combined.1 Today, it's hard to dispute that the USN is larger than that, and this obviously leads to the question of why we need such a big fleet. Is it extravagance and empire-building by the Navy? Is it because we're using our ships inefficiently? Could we cut back substantially without compromising the vital command of the sea?

I believe the answer to all of these questions is no, and the entire theory is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of both the roots of the two-power standard and the changes in the roles and capabilities of seapower throughout the 20th century.

First, some history. The two-power standard was first devised in 1889, when the main threat to Britain was essentially an alliance of France and Russia. It was the first time that a naval strategy was put forth to the public so clearly2 and it was a good match for British needs at the time. The French and Russian fleets were based in European waters, where geography gave the British a major advantage. But even this equilibrium lasted barely more than a decade. In the aftermath of the Sino-Japanese War, the Russians gained access to the warm-water Port Arthur, giving them a base for commerce raiders well outside British control. Shifting fleet units to deal with this new threat might well have eroded the vital strength in European waters, and Britain instead ended her "splendid isolation" and signed an alliance with Japan in 1902.

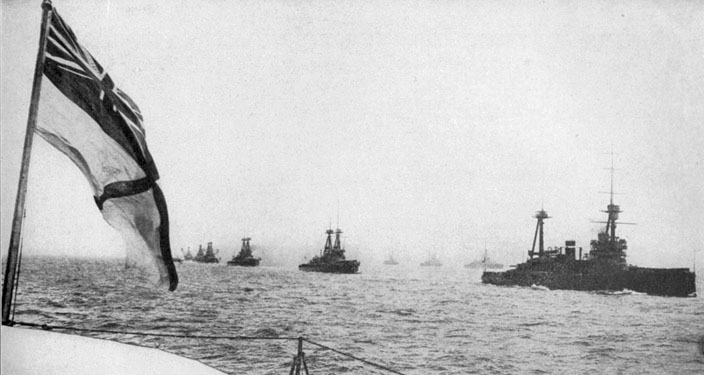

But even as this was happening, a new threat was rising that comprehensively undermined the two-power standard. Germany, under Alfred von Tirpitz, had decided to build a navy because that was what all of the cool countries had done3 and had the industrial resources and political will to challenge Britain at sea. Rising German power pushed France, Russia and Britain together, and from 1908 onward, the two-power standard was abandoned as the strategic environment changed. By this point, the third-ranked Navy was that of the US, which British opinion, both public and official, treated as a natural ally instead of a potential rival.4 With all other potentially hostile navies far behind Germany's in strength and with the fiscal burden of facing down the Kaiser a source of controversy, the British reevaluated their requirements, and in 1912 finally cleared things up with a new standard, sixty percent superiority over the second-ranked navy. This was maintained more or less throughout WWI, and before the Admiralty could figure out what it wanted postwar, the Washington Naval Treaty set the force levels based on diplomacy rather than strategic need, although it did ensure that Britain had superiority over potential enemies.

Obviously, even the British didn't think of the two-power standard as some sort of universal truth of sea power, merely a reaction to the circumstances they found themselves in. As such, there's no reason that it should apply to the USN today. But that's only half of the story. In 1889, seapower was pretty simple. Battleships existed to beat the enemy fleet, giving their owners command of the sea, while cruisers would enforce that command, protecting or raiding commerce. While the torpedo boat existed, it was yet to evolve into the destroyer, and Holland had yet to sell his submarines to any navy. The Wright Brothers wouldn't fly for 14 years, and it would take a quarter-century for aircraft to become even remotely relevant at sea. If the RN could beat the French and Russian battlefleets, its cruisers could operate essentially unmolested. And beyond the effects of controlling the sea, the ability of any ship to affect events ashore was extremely limited. Sure, the battlefleet could bombard coastal targets, but important targets could be expected to have modern, well-manned defenses, making that very hazardous.

Every aspect of this has changed in the last 125 years. Today, command of the seas requires controlling not only the surface, but also what passes beneath and above it. Dealing with this is going to require more forces, and figuring out their level will take a more sophisticated analysis than simple numerical comparisons. But even more important than that is the new capabilities that naval forces have gained. Even if the Grand Fleet had been 10 times the size of the High Seas Fleet, it's arguable that it wouldn't have made any significant difference to the war.5 The extra ships would have merely been more vessels at anchor in Scapa Flow, carrying out the vital duties of enforcing the blockade. Today, thanks to aircraft carriers and cruise missiles, ships are capable of destroying targets hundreds of miles inland. A margin of superiority that a century ago would have been essentially wasted is now the ability to destroy more targets more quickly than would have been possible otherwise.

And that more than anything else is why the USN is built the way it is. Is it oversized if its only task is protecting our command of the seas? Maybe. After all, just as sea-based aircraft can strike land targets, land-based aircraft can go after targets at sea, and sea-based airpower is probably the best way to deal with that. Figuring out how many carriers this would require isn't really something we can do from the unclassified world. But even more importantly, our carriers are designed to go after targets ashore, and the importance of a mobile airbase bringing a substantial amount of firepower with it should not be underestimated, even if the enemy has no navy at all. We saw this in Afghanistan in 2001, and we will undoubtedly see it again no matter where trouble pops up in the future.

1 To be pedantic, the two-power standard applied to capital ships, not total fleet size, and that it was often 2 powers + 10%. ⇑

2 I know this sounds insane, but I am very serious. Strategic thinking as we know it essentially didn't exist at sea before the late 19th century. There's a reason we don't read any naval strategists before Mahan. There aren't any. ⇑

3 This is only barely an oversimplification of German strategic thought. ⇑

4 Americans didn't really get this memo, but that's an issue for another day. ⇑

5 The counterargument is that with that margin of superiority, the British would likely have tried Fisher's scheme to attack the Baltic coast of Germany, which could have made a lot of difference. But that was a risky strategy regardless, nowhere near the straightforward contribution of a carrier or a destroyer loaded with Tomahawks. ⇑

Comments

I want to push back on point 2 a bit. There are definitely comments from as far back as the 1600s with british statesmen saying something to the effect of "our strategy is to keep europe divided so no one can threaten us." Granted, these strategies weren't usually put to the public, but people did think about strategy even if they didn't usually talk about it in public or write books about it.

On point 3 I agree completely. Admirals are gonna admiral...

Note that I said "at sea". Strategy existed elsewhere, but the sort of analysis Mahan did was revolutionary, and the first section of his book is just "here's why naval history is actually a thing".

@cassander: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37iHSwA1SwE

A complete pig's breakfast!

Didn't we lose Afghanistan due to a failure to properly secure our supply lines?

It seems like the ability of sea-power to project inland is a powerful tool but encourages bad decisions.

We lost Afghanistan because political will to keep stabilizing the government ran out. Note that before the evacuation, we had zero combat deaths there in 2021. But I was talking 2001, not 2021, and the chances of the US not going into Afghanistan in 2001 were zero after they refused to turn Bin Laden over to us.

I would say that land power encourages far worse decisions on the whole.

bean:

You sure it wasn't just one person?

Because there was no mass public movement calling for pulling out that I could see.

bean:

Being continental or maritime does seem to affect the very character of societies.

@Anonymous

I will decline to answer that on the ground that it's getting too close to Culture War. My point was that the situation in Afghanistan was a political result, not one dictated by military considerations.

That, and it definitely alters the options they have available. The only way to keep the US out of Afghanistan in 2001 was to make it so that there was no way we could. That's going to be the result of an extremely different foreign policy than we have now.

I wouldn't say it was political will. Mankind has been making client-kingdoms for thousands of years. I struggle to think of one worse on a results-per-dollars-spent basis.

I struggle to see the logic of the original criticism in the first place.

"You don't need to be in a better position than the British at the start of WWI."

Errr... Britain and the British Empire got smashed in WW1. Admittedly, just about every other Euro empire got smashed even harder. But that doesn't mean that Britain came out well.

It's hardly a target to aim for.

As for a more powerful RN actually helping? There is the idea that if a serious supply route could be maintained to Petrograd, that both Russia might have remained stable enough to stay in the war (yay) and not turn communist (much bigger yay).

And if there was an effective landing craft, mine clearance and littoral combat fleet (not something that c.1900 RN planners had the faintest idea of starting to think about) that the Gallipoli landings might have worked, and opened up the Black sea.

@Doctorpat, eh, before WWI England had 700 different artisanal cheeses, more than France, the problem is that the cheese types got standardised for the war economy, and most of the cheesemakers remained in the fields of Flanders, so when the war ended many of those cheeses could not be produced again, as the knowledge was lost... :-(

A lot of the stereotypes about bad English cooking are the fault of the wars and post-war rationing and nationalization.

Doctorpat:

All true, but could the British have retained their standing with an undivided US existing? It's quite possible that the British were in a position that was pretty close to optimum given their resources.

@doctorpat

Their standing as the number 1 power? No, the US was bigger and richer. But they could have been more than just another big european country. The British government destroying their cheese industry is but one small example of how terrible economic policies ruined the british economy and squandered literally centuries of them being much richer than the rest of Europe in just a few short decades.

https://imgur.com/a/FpCuEY6 http://itscheese.com/cheeses/governmentcheddar

This is not the right venue, but I would be interested to see an effort post on what exactly the British did wrong between, say, 1925-1975, and how they could have done better.

@Humphrey

Given that they were the worst performing non-communist major economy in europe, you could say "almost anything."

@Humphrey

A lot of the problem goes back to WWI. The British economy took a battering during that, and then there was the Great Depression. WWII wasn't great either, with economic attack from FDR and actual attack from Hitler. Postwar, it was essentially a commitment to full employment, which came down to supporting the existing structure even when that made no sense and was causing economic problems.

On a meta level, I wonder to what degree American interest in the fall of the British Empire and historic British interest in the fall of the Roman Empire are both motivated by the question: "What did they do wrong, and how can we do better?".

Typo: