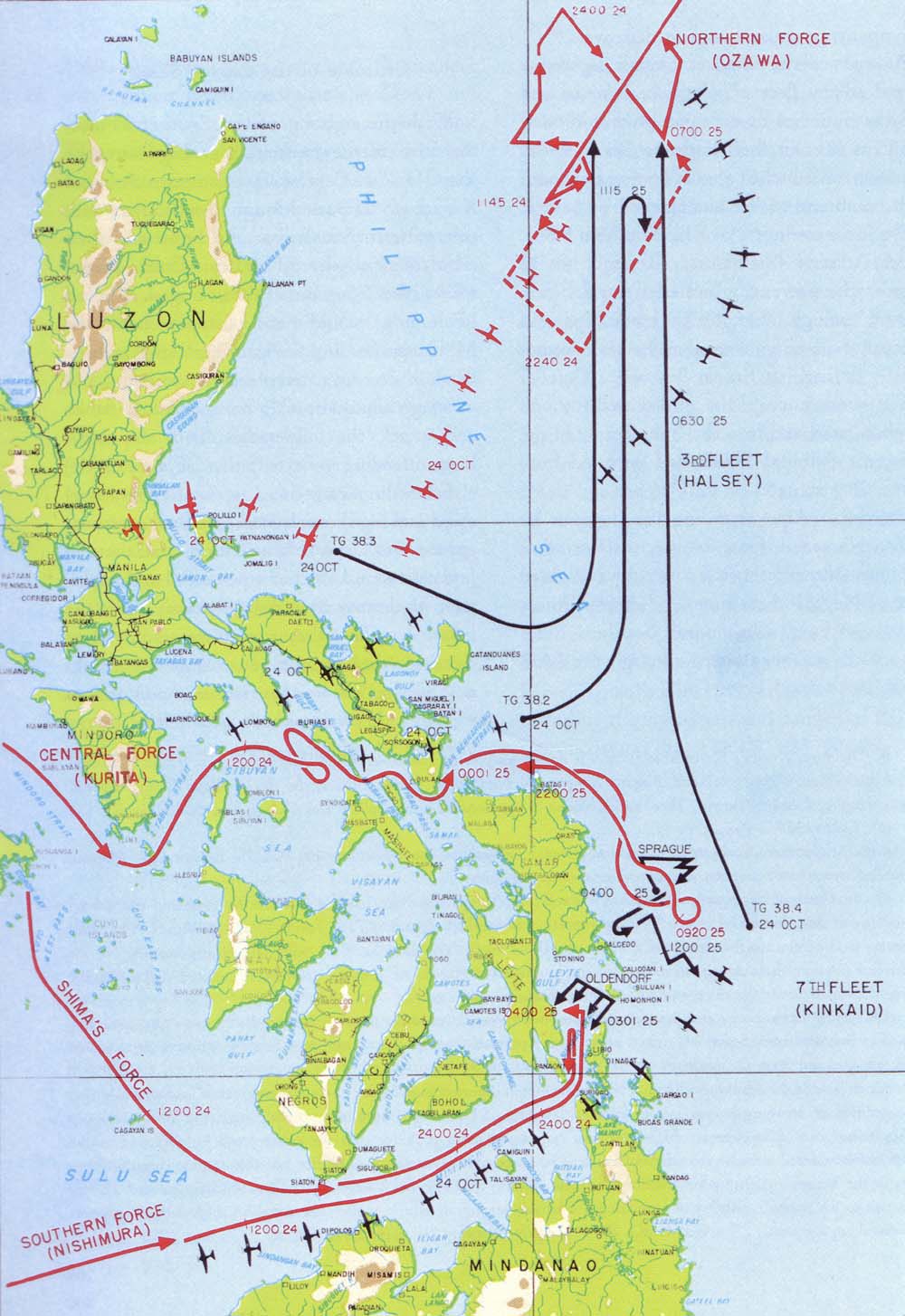

Today is the 76th anniversary of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and as such, it's worth looking at one of the most controversial elements of the battle. The Japanese plan to counter the American landings on Leyte in the Philippines was to distract the American carriers covering the landing with a carrier force of their own coming in from the North, and then pincer the amphibious landing with two battleship forces. One of these would approach from the south, while the other would come from the west, pass through the Philippine archipelago and fall on the landing force from the north. On October 24th, both the Southern Force and Center Force were located and attacked by aircraft. Center Force took the brunt of the attack, which sunk battleship Musashi, sister to Yamato, but left the other four battleships and most of their escorting cruisers intact. Admiral Kurita, in charge of Center Force, briefly turned to the west, but resumed his course for Leyte shortly before nightfall. The Japanese Southern Force never wavered, and was destroyed that night in the last clash of big-gun warships in history.

Iowa follows other battleships of Third Fleet to sea

Shortly before Kurita turned back towards San Bernadino Strait, the route he would take to reach Leyte, Admiral Halsey's planes finally located the Japanese carrier force well to the north under Admiral Ozawa. Northern Force's job in all of this had been to draw Halsey off, but Ozawa's attempts at producing radio traffic for the Americans to intercept had failed1 and his force, the one the Japanese wanted the Americans to find, was actually the last to be located. Halsey immediately jumped at the bait, sending all three carrier groups under his command tearing north, planning to attack Ozawa at dawn. Based on the reports of the pilots who had attacked Center Force, he believed that it was "beyond doubt that Center Force had been badly mauled with all of its battleships and most of its heavy cruisers tremendously reduced in fighting power and life."2

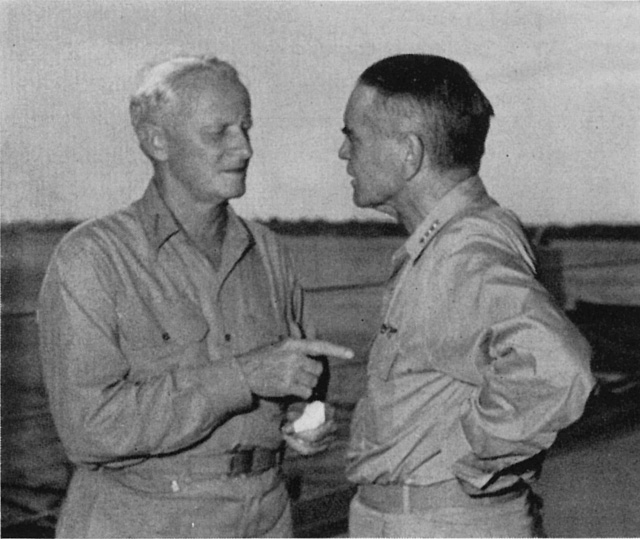

William Halsey

This decision is one of the most controversial in American naval history. The 65 ships in Halsey's three task groups were more than sufficient to sink both Japanese forces, but Halsey was focused on the Japanese carriers alone, worried that they would escape as they had done at most of the war's previous carrier battles, most notably at the Philippine Sea in June. Although Halsey didn't realize it, this was precisely the wrong thing to do. The Japanese had not focused on training large numbers of carrier pilots, and losses throughout the war, most notably at Philippine Sea, had left their decks empty and the ships reduced to use as decoys.

Operations around Leyte Gulf

Reports had begun to arrive from American scouting planes that Kurita was headed east again, and several of Halsey's subordinates disagreed with his decision. Admiral Gerald Bogan, commander of TG 38.2, called Halsey personally over TBS, pointing out that the navigation lights in San Bernadino Strait had been turned on, breaking the usual blackout. A staff officer brushed him off, and a similar message from Willis Lee, commander of TF 34, Halsey's battle line, was also ignored. Bogan proposed detaching TF 34, composed of battleships Iowa, New Jersey, Washington and Alabama, as well as two heavy and three light cruisers and escorting destroyers, to cover San Bernadino Strait, with air cover provided by his carrier group.3 Lee was willing to take his ships out without air cover, and make sure that Kurita didn't threaten the landings.

Thomas Kinkaid

Halsey's decision to move his entire force against Ozawa is somewhat puzzling at this remove, but the consequences were made much worse by the divided nature of the American command structure. Halsey was commander of Third Fleet, which represented the core of the USN's power in the Pacific. But the landings themselves were the responsibility of Thomas Kinkaid's Seventh Fleet, which reported to MacArthur instead of Nimitz. Due to a complicated mess of interservice politics and MacArthur's ego, the chain of command for the two forces didn't meet anywhere below the Pentagon, and passing messages between them was difficult. Halsey's job was to deal with the Japanese fleet if it came out, while Kinkaid was responsible for close-in protection of the landing force. However, a general attitude prevailed among his staff that Halsey would take care of any threats from the north.

Willis Lee

This impression was confirmed by a signal that Halsey sent to Third Fleet at 1512 on the 24th, shortly before Ozawa was located, which Seventh Fleet also picked up. In it, he sent a "Battle Plan", directing that the available battleships and their escorts "will be formed as Task Force 34" under Lee, which would "engage decisively at long ranges" while the carrier groups kept clear. Everything hung on the meaning of "will". Halsey meant this as a plan that might be executed in the future, saving time and confusion if he decided to do so. However, Kinkaid read it as an order for the present, and assumed that TF 34 was covering the San Bernadino Strait. He was far from alone in this reading, with both Nimitz and the Pentagon staff making the same assumption. As a result, all three groups assumed that San Bernadino Strait was still covered when Halsey announced he was headed north.

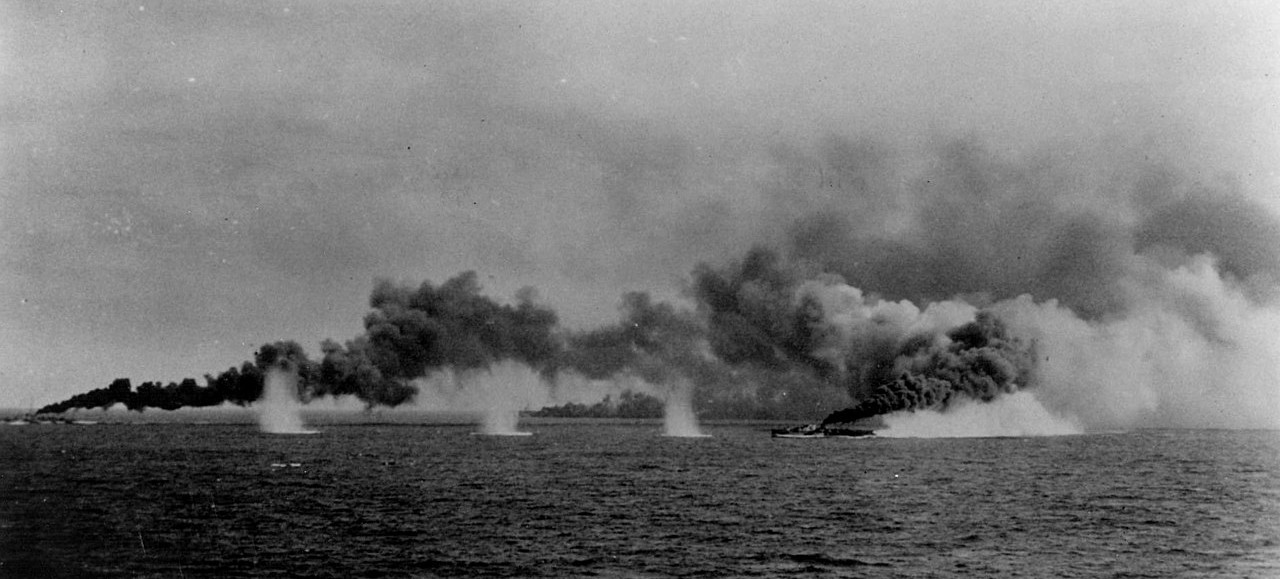

Destroyers lay a smokescreen amid Japanese shell splashes off Samar

Some members of Kinkaid's staff were not so sure that they were reading the message correctly, and at 4 AM, they convinced him to check with Halsey about the location of TF 34. This message didn't reach Halsey for two and a half hours, and it wasn't until 0705 that he replied that the ships were with the carriers. Six minutes earlier, Taffy 3, one of Kinkaid's escort carrier groups, had, as Samuel Eliot Morison put it,4 "received a much more emphatic answer in the same sense from the muzzles of Kurita's guns". Unopposed, Kurita had slipped through the San Bernadino Strait just after midnight, and fell upon a massively outmatched collection of smaller ships, who turned him back in probably the most glorious moment in the history of the US Navy.

Ships of the Northern Force under air attack

Kurita's encounter with Taffy 3 caused near-panic throughout the American forces near the Philippines. Kinkaid quickly requested help from Halsey, but Halsey's pilots had sighted Ozawa just minutes after Kurita appeared over the horizon, and his planes were busy destroying Northern Force by the time the news reached him. TF 34, including Massachusetts and South Dakota as well as the four battleships detailed on the 24th, had been formed at 0240 and stationed ahead of the carriers, both to protect against any encounter with Japanese surface ships in the dark and to put them in a better spot to pursue and sink any survivors of the air attack with gunfire. By 1115, Lee was only 42 miles from the crippled Northern Force, probably no more than an hour from being able to open fire.

Nimitz and Halsey in 1943

Back in Hawaii, Nimitz was growing increasingly confused. He was unsure of the whereabouts of TF 34, and eventually decided to simply ask Halsey that question. The message as sent read WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR REPEAT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR. But at this point, a bit of American communication protocol intervened. To make cryptanalysis more difficult, all messages were padded with bits of nonsense at the front and back, separated from the body of the message by double consonants. The officer in charge of sending it chose TURKEY TROTS TO WATER as the front padding, and THE WORLD WONDERS as the back padding. When the message arrived aboard Halsey's flagship New Jersey at 1000, the signal staff forgot to strip off the back padding, so the message as delivered to Halsey was WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR REPEAT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR RR THE WORLD WONDERS. The padding, from the poem The Charge of the Light Brigade, changed the tone from a request to clear up some confusion in Hawaii to a reprimand.5 An hour later, Halsey ordered TF 34, covered by Bogan's carriers, to turn south and try to help Kinkaid. He later told Morison that it was the only move of Leyte Gulf that he regretted.

Center Force on the 25th

Unfortunately, it was too little, too late. TF 34 was too far north, and couldn't possibly reach San Bernadino Strait until 0100 on the 26th. Some of this was because its destroyers were low on fuel, forcing speed to be reduced so they could take on more from the battleships and delaying the ships over two hours. At 1622, TG 34.5 was formed, centered on Iowa and New Jersey, and sent south at 28 kts. This was a rather odd decision, as the resulting force was heavily outnumbered by Kurita, although it did contain the only battleships fast enough to arrive with any hope of making a difference. But even this wasn't enough, and Kurita had passed through San Bernadino Strait to safety three hours before the Americans arrived. The only Japanese ship still in the area was the crippled destroyer Nowaki, who had narrowly escaped Iowa back in February, but wasn't so lucky this time.

New Jersey as seen from Iowa on the 26th

So what do we make of Halsey's decision? Traditionally, it's been heavily criticized. With the benefit of hindsight, it's easy to say that TF 34 should have been left to guard San Bernadino while the carriers went after Ozawa. But there are two main problems with this view. First, by 1944 it was well-understood that the carriers were the center of gravity of a fleet, and the Americans hadn't yet realized how badly the Japanese had screwed up their pilot training pipeline. Halsey's orders prioritized sinking the Japanese fleet, and he thought he was doing just that. Second, there's the issue of the carrier's vulnerability to surface attack at night, which I've addressed elsewhere, and which likely led him to ignore Bogan's advice. On the whole, Halsey made a reasonable decision, although it turned out to be the wrong call in retrospect.

Battleship-carrier Ise, one of the survivors of Ozawa's force

Somewhat less reasonable are his choices on the 25th. While it wouldn't make sense for him to turn back as soon as Kinkaid's first message reached him, his actual decision was the worst of both possible worlds. If he had held course, the survivors of the Northern Force would have been annihilated. But by the time he reversed course, he had to have at least suspected he would be too late, and he didn't push to cover San Bernadino as quickly as he might have. Most puzzling is the decision to detach TG 34.5, which would have had an extremely tough fight against Kurita, despite Halsey's own presence aboard New Jersey. On the whole, it was a lackluster performance from a competent admiral, but one that perhaps doesn't deserve the censure it has received over the years. That said, I do personally wish he had managed to arrange one final battleship showdown, and give Iowa a chance to prove herself in the combat she was designed for. Some day, I'll take a look at what might have been had he done so.

1 One of my sources traces this to a broken radio antenna, but I'm not sure if this is actually the case. ⇑

2 Morison, Leyte, p.194. ⇑

3 These ships were normally part of the various task groups that made up TF 38, the unit the carriers fell under, but could be separated and put under Lee. Massachusetts and South Dakota were also present, but they were with a different carrier group that was far away from San Bernadino Strait. ⇑

4 Leyte, p.292. ⇑

5 This wasn't the only time padding got mistaken for content. The request to SEND US MORE JAPS from the defenders of Wake Island was chosen as padding by the ensign responsible for encoding it in the belief that nobody would be stupid enough to think it was real. ⇑

Comments

Even Hornfischer acknowledged (in The Fleet at Flood Tide) that there was no way Halsey could have known at the time that Ozawa's carriers weren't carrying - that there was no intelligence suggesting that THIS time, the IJN hadn't been able to replace the losses to their carrier air groups the way they had in time for every previous battle - and Hornfischer generally writes like he has a personal vendetta against Halsey.

Another bit of context: in the months between Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf, Spruance's handling of the former battle had been widely criticized in Navy circles. A lot of flag officers believed that his decision to stand on the defensive, which was the polar opposite of established carrier doctrine (and also contrary to the advice given by his staff) had allowed the Japanese carriers to escape from nearly certain destruction in that engagement. I don't know if Halsey participated in the backbiting, but certainly he was not about to repeat the "mistake" of the Marianas.

As to the 25th... Halsey appears to have taken "the world wonders" as not only a personal attack but also a thinly-veiled attempt at micromanaging the battle from Pearl Harbor. One way to make sense of Halsey's subsequent actions is that he was acceding with poor grace to an implicit demand from Nimitz - one that he felt he couldn't refuse despite knowing it was a bad idea and overtaken by events. Granted, that's still not a flattering picture, but perhaps it's more comprehensible than "Halsey suddenly forgot how speeds and distances work."

Unfortunately, this is the kind of stuff that often gets cut to make the post readable. I didn't want to get too deep into psychoanalyzing Halsey. Plenty have already done that, and it's not the point of this post.

So, the split command structure basically led to internal sigint? I suspect I'm about to be told this happens all the time.

Yes and yes. Not as much these days (the US at least has more or less gotten rid of split commands, and the messaging systems don't allow it) but back then, it was reasonably common.

So, if the battle were fought today, it would be micromanaged from Pearl Harbor?

@bobbert: today they'd be lucky if the micromanagement is only as low level as PACOM.

Put it this way, @bobbert: LBJ boasted that the air campaign in Vietnam "(couldn't) hit an outhouse without (his) permission." And that was with mid-60s communications technology.

Hornfischer's book "The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors" breaks down this battle much more than "The Fleet at Flood Tide." The reason that the radio room didn't remove "the World Wonders" was because it made sense based on the rest of the message. It is an unfortunate error in comms and the original send should have used that language for that message.

That book isn't much nicer to Halsey, but I think part of that is the fact that the Navy in the post war world didn't honor Taffy 3 like they deserved to be. The biggest mistake that was made was the lack of a single responsible commander for the operation.

With today's comms tech, they often fight the battle from the US. President Obama literally watched the Bin Laden Raid as it happened.

The "What if..." I really wonder about is what would have happened if Taffy 3 hadn't succeeded in driving back the center fleet? If the Japanese had a clear picture of what they were facing and could push though, exactly what kind of damage could they have caused?