One of the major issues that I didn't discuss in my early coverage of military spaceflight was operations by nations outside of the United States, most notably the Soviet Union. The Soviets were somewhat slower to adopt satellite reconnaissance than the United States, as they were able to take advantage of the openness of American society to gather information on their enemy. Instead, they spent the late 50s protesting the "illegal" American satellites, although development began on recon satellites shortly after Sputnik went up.

A Zenit capsule

The Soviets faced several challenges. They were shorter on technical skills than the Americans, limiting the number of programs they could run at one time, and because, unlike the US, they had not spent the last decade and more building up their strategic reconnaissance capabilities, they were also short on the sophisticated cameras that would be needed by a reconnaissance satellite. Fortunately, they could kill two birds with one stone, by using the same Vostok capsule that carried Yuri Gagarin into orbit, but with a bunch of cameras instead of an astronaut. This was very useful, as it meant the cameras and film were kept in a pressurized environment, and the cameras could be reused, although it required a significantly larger booster than the American system.1 This program, codenamed Zenit, lasted until 1994, although with significant evolution over its lifespan. The early versions had no ability to alter their orbits, and relied on batteries, limiting them to only a few days in orbit, while later versions could stay up for two weeks thanks to solar panels and could remain over a specific area for most of their operational life.

The weight of the Zenit capsule meant that midair recovery, like the Americans used, was out, and the solution was to land the capsule on land, much as was done with Vostok and all later Soviet and Russian manned spacecraft. This recovery method imposed an unusual limitation, particularly in the early days of the program. The usual landing zone was in the Kazakh steppes near the launch site at Tyuratam, but any delay in retrofire would see the capsule land instead in the wastes of Siberia. This was annoying in the summer, but nearly disastrous in the winter, so the Soviets tended to take something of a break from their otherwise very busy launch schedule. The early flights, the first of which took place in late 1961, had been enough to convince the Soviets of the value of reconnaissance satellites, and in 1963, protests against the US program were quietly dropped. It took a few years for the Soviet program to ramp up, but starting in 1967, Soviet photographic satellite launches overtook those of the US at 22 to 19, the ratio increasing to 29 to 16 the next year and continued to climb through the 70s as the US launched fewer, more capable satellites and the Soviets flooded LEO with lots of short-lived birds.

A Yantar capsule (left) with other recon satellite paraphernalia

They continued to bring the cameras back with the second-generation Yantar, although it was designed from the start for recon work, and had two film-return capsules to stretch its time on orbit to 30 days. The first Yantar flew in 1974, and was soon followed by an improved version with various tweaks, including 50% more endurance and better cameras. In 1982, Yantar provided the basic architecture for the first Soviet electro-optical satellites, Yantar 4KS-1, which went up in parallel with the Geizer relay satellites. But Russian cameras and transmission systems were still fairly primitive, and the last film-carrying Yantar didn't fly until 2015. It served alongside the Orlets systems, designed to provide warning of strategic attack. Orlets 1 had 8 film capsules and a 60-day lifetime, while Orlets 2 had 22 and could stay active for 180 days. It also appears that the basic Yantar design continues to underlay current Russian satellites, such as the Persona series that currently seems to make up the bulk of their recon capability.2

An Almaz in a museum

The Soviets also looked extensively at manned operations for reconnaissance. Soyuz was originally designed as an integrated space station and crew shuttle, although the station part soon fell victim to political infighting and was replaced by a rival design bureau's Almaz, with the shuttle craft staying around to become by far the most common means of getting people into space. Three Almaz prototypes were flown, discussed earlier for being fitted with a space gun, although their main job was to carry cameras. The Soviets quickly decided that it was generally easier to observe the Earth from unmanned satellites,3 and three were converted into heavy radar satellites as Almaz-T. Some military experiments survived aboard the civilian Salyut and Mir stations, although details are not exactly clear.

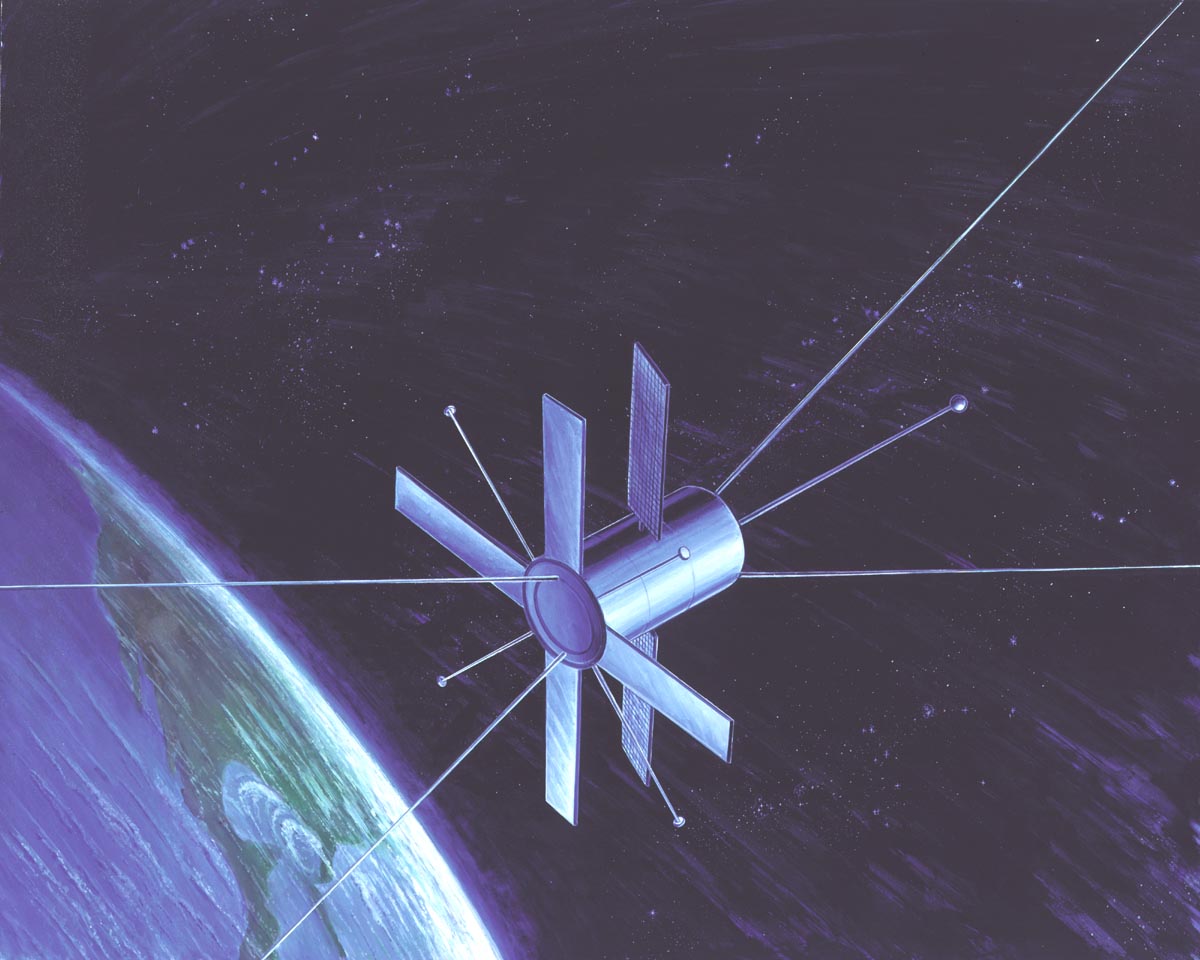

A Soviet ELINT satellite

The Soviets also invested in two series of ELINT satellites. We've already looked at the US/EORSAT, intended to track ships, while the Tselina series handled the more conventional cataloging of emitters. The Strela series were officially used for store-and-foreward communications, where they would record a message over one area, then transmit it to a receiver on the ground elsewhere. What most sources seem not to realize is that there was no requirement the message come from a Soviet source, and it is likely these were used mostly for intercepting other people's communications from relatively low orbit, another example of the Soviet tendency to replace high technology (in this case, the massive antennas and low-noise amplifiers of the US COMINT effort) with a lot of simpler systems. It is also likely that the Lourdes SIGINT station in Cuba was primarily a ground station for SIGINT satellites instead of conducting direct listening, as it is over the horizon from Florida, and didn't start operations until the early 60s. Also worth a brief mention is the Oko program, the Soviet equivalent of the US DSP. This system, intended for missile warning, is famous mostly for providing the false signals that Stanislav Petrov famously ignored in 1983.4

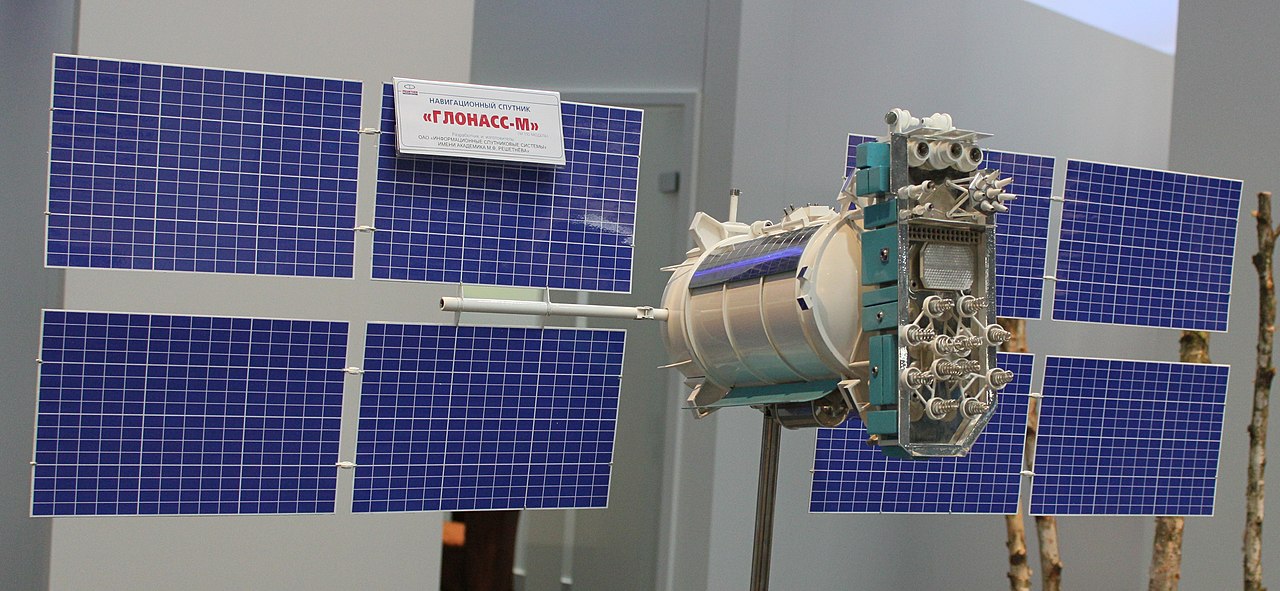

A GLONASS satellite

The fall of the Soviet Union left the Russians with several problems. First, their main launch facility, Baikonur/Tyuratam, was now in Kazakhstan, although they were able to lease it from the newly-independent government. Second, their system had been built around flying lots of short-lived satellites, which meant that as their economy collapsed, active satellite numbers fell sharply. Through the early 90s, they were able to keep things going by flying leftovers from the Soviet program, but even at a reduced rate, they were essentially out by the late 90s, producing a massive gap in their space operations. They even came close to losing the GLONASS system, the Russian equivalent to GPS, before that was made a priority when Putin took power, and that system takes up a third of the Russian space budget even today. The surveillance satellite system has never recovered to the heights of the Cold War, but the Russians continue to fly surveillance satellites of various types.

Of course, Russia and the US were far from the only countries to investigate the potential of space platforms for gathering information about the Earth. We'll take a look at the rest of the world next time.

1 There was another potential problem. If the retrorocket failed, the capsule would come down eventually thanks to air drag, and there was a decent chance it would land somewhere the Americans could get it. The obvious solution, used first on Kosmos 50, was a self-destruct charge. ⇑

2 Note that the Yantar-derived bit in Persona is the service module, which was always discarded before recovery. They're not bringing these down any more. ⇑

3 This may have also been political, as the guy running the design bureau behind Almaz, Vladimir Chelomey, managed to make himself quite unpopular in the Soviet defense establishment. ⇑

4 As an aside, I think Petrov is often given too much credit for this. It was a fairly routine case where the person on duty noticed a pretty clear false alarm and acted as if it was false. More broadly, most people don't want to blow up the world, and tend to be quite careful about not doing so unnecessarily. ⇑

Comments

Re: Stanislav Petrov, it's worth noting that part of his decision against rasing the alarm was ignorance of US first strike doctrine. Other than his knowledge of the system's technical unreliability, he also thought that a launch of only a few missiles didn't make military sense - if you wanted nuclear war, you'd go all out[1]. But a limited "decapitation strike", followed by demands for capitulation, was (at least part of) US nuclear first strike doctrine at the time.

[1]https://www.brightstarsound.com/worldhero/themoscow_news.html "First, missile attacks do not start from just one base. Second, the computer is, by definition, brainless. There are lots of things it can mistake for a missile launch.” "

The link got mangled:

https://www.brightstarsound.com world[underscore]hero the[underscore]moscow[underscore]news.html

To the Stanislav Petrov case, is it possible to find how many false signals actually were there? Because I would say this much defines if his reaction was intelegently calm, or pretty standard.