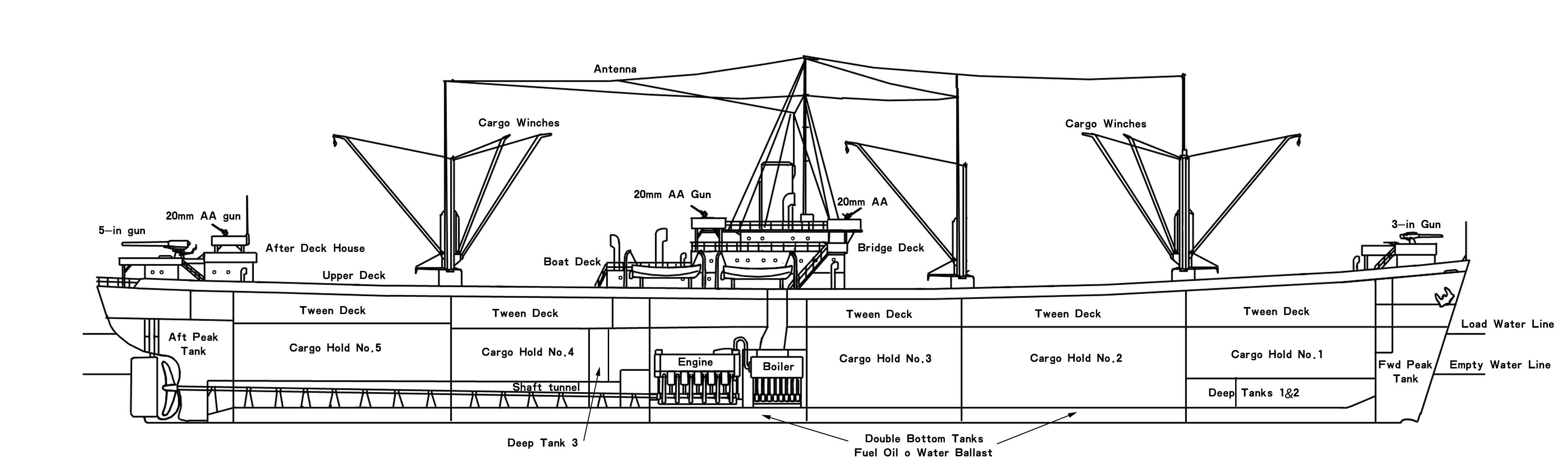

In late 1941, the US was gearing up for war. The nation's vast industrial might, idled by the Great Depression, was harnessed to produce material both for Britain and for America's own defense. But the biggest problem would be getting the products of the Arsenal of Democracy overseas, as the fighting fronts were far from American shores, and to do that, merchant ships were required. Efforts to rebuild the nation's merchant marine had been ongoing since 1936, but were not far enough along to bridge the gap, particularly in the face of the depredations of German U-boats. The answer was an emergency shipbuilding program of 9 yards to produce vast numbers of vessels capable of carrying 10,000 tons of cargo at reasonable speed. The first was launched on September 27th, 1941, and the type was dubbed the Liberty Ship.

But even the prewar program, scheduled to deliver 267 Liberty ships in 1942, was rendered instantly inadequate by the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the subsequent U-boat campaign along America's coast. 6.4 million tons1 of merchant shipping would be lost in the first half of the year, eclipsing the 5 million tons planned for completion by the Maritime Commission that year. That January, the target was raised to 8 million tons, with the target for 1943 set at 10 million. Expanding the yards to meet these targets, as had been done in 1941, was probably impractical. Instead, construction would have to be sped up, with the 250 day construction times of the first batch of ships falling to 105 days, with ships going from keel-laying to launch in only 60. That would allow six ships per way per year, a 50% increase over the pre-war schedule.

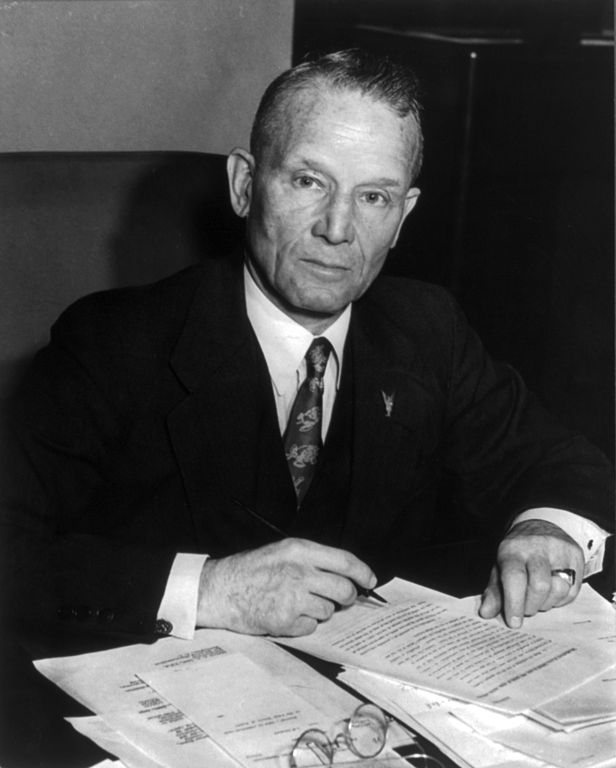

Emory S. Land

But even this frantic pace wasn't enough to satisfy the appetite of either Roosevelt or the US Army, who wanted to get American troops overseas in large numbers. In February, Roosevelt ordered retired Admiral Emory Land, chairman of the Maritime Commission, to produce 9 million tons in 1942 and a staggering 15 million tons in 1943. Land was not confident that production in existing yards could be pushed any higher, and as a result, another round of expansion began. Some of the new ways were attached to existing yards, most notably those of Henry Kaiser, who had already begun to impress by getting a ship launched 71 days after the previous ship went down the ways of his yard in Portland, with the yards in Richmond not far behind. In total, the area around Portland would have 31 slips for the Emergency Program, while the Bay Area would reach 33, including a new 6-slip yard at Sausalito. More yards of that size would be built at Providence, Rhode Island, Brunswick, Georgia, and Jacksonville and Panama City, Florida. Lastly, famed industrialist Andrew Higgins, inventor of the "Higgins Boat" that would carry so many men to beaches around the world, received a contract for a unique yard at New Orleans which would build Liberty Ships on four parallel moving assembly lines, projected to turn out 195 ships during 1943. This expansion was enough to remove any possibility that shipyards would be the limiting factor in shipbuilding during 1943, with steel and engines likely to be the bottlenecks instead. Ultimately, at its peak the Maritime Commission would have 267 full-size slipways under its control, producing ships of all types.

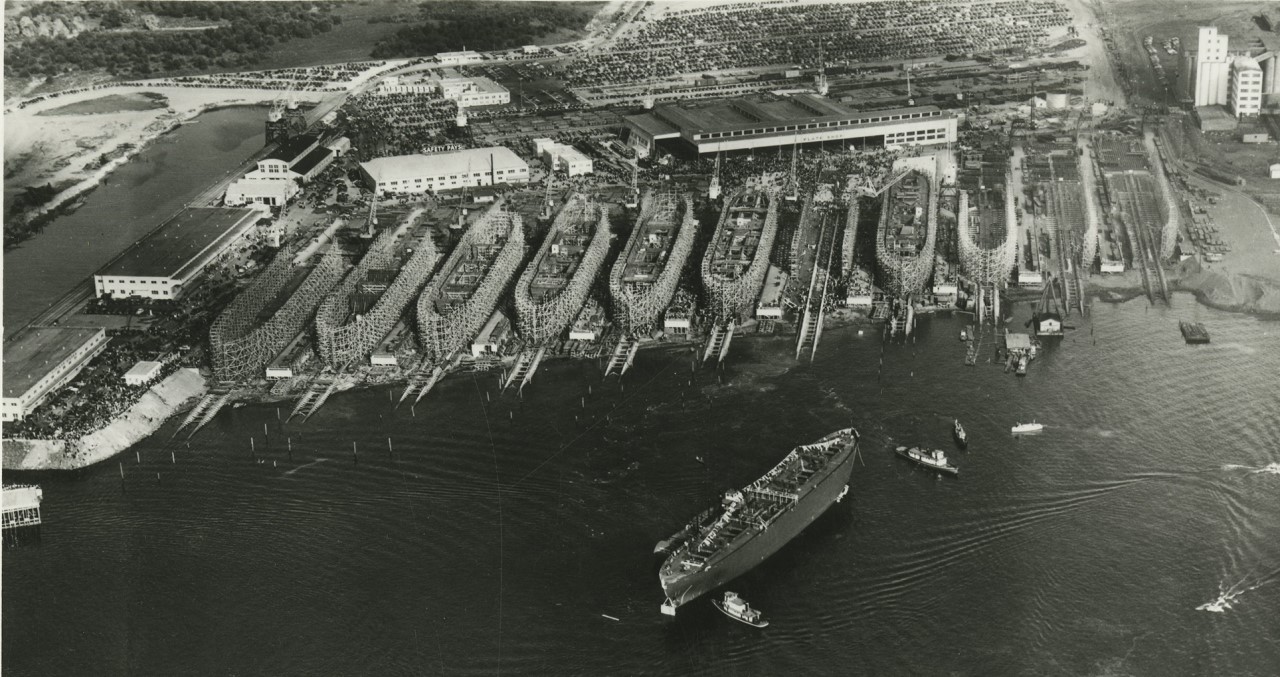

Oregon Shipbuilding launches one of many merchant ships

But all of this was to come in early 1942. As late as April, it looked doubtful that they would be able to reach the 8 million tons of the original plan, much less FDR's 9 million ton goal. Deliveries ran behind schedule, and the public pushed for reforms in the management of the shipbuilding program. But by May 22nd, Maritime Day, the picture had dramatically changed, and the Commissioners were able to cite cases like a West Coast yard that had just delivered three ships which had spent an average of 65 days on the ways, 40 days below the Commission's target, and only a small proportion of the 57 vessels delivered that month. In June, things were even better, as 67 vessels were delivered and average time from keel-laying to delivery fell from 151 days in May to 118 days. This included many ships from yards of the second and third waves, which were just getting started, and the more experienced yards could do far better. Richmond No.1 managed 69 days, while Oregon Ship turned their vessels out in an incredible 54 days each. In fact, it appeared that the Maritime Commission had done their work too well, and would be able to meet Roosevelt's goals with lots of capacity to spare. This turned out to be a good thing, as the demands of global war demanded more than just merchant ships, and while the emergency yards weren't set up to build proper warships, they were more than capable of constructing LSTs and escort carriers, and several yards, most notably Kaiser's in Vancouver, Washington, were turned over to such purposes.

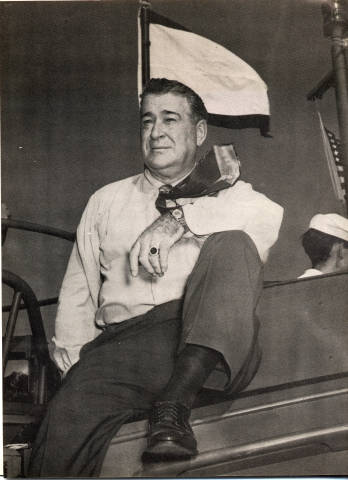

Henry J. Kaiser

Matters came to a head in late June, when FDR appeared to request another 3.4 million tons of shipping in 1943. There wasn't enough steel available for this, and after a lot of wrangling between the Maritime Commission, the Navy and the War Production Board, it was finally decided that the total target for 1942-1943 would be 24 million tons of shipping, the target before FDR's request. This left the Maritime Commission with a lot of extra capacity, and the decision was made to cancel the radical new Higgins shipyard, which the Maritime Commission gave only a 50% chance of working as promised. The basic plan was to build the shipyard around a huge assembly shed, where sections for the ships would be prefabricated before being taken out to the four mile-long moving slipways, where the ships would be assembled across 11 stations and then launched. Two of the lines would be manned by blacks, the other two by whites, in hopes of avoiding racial tensions. Competition between each pair of lines would spur the workers to greater productivity. However, the projected costs increased repeatedly as construction began, and the project was the furthest from completion when the Maritime Commission found itself with excess capacity.

Andrew Higgins

Andrew Higgins was furious about the cancellation of the project, and quickly brought all the political pressure he could muster, ranging from Senators to labor leaders, to bear to undo the Commission's decision. He claimed that it was the fault of the traditional shipbuilders in the Northeast, who feared competition from him after the war. Several Congressional committees immediately began investigations, and at least one witness was confused enough to be unsure of which committee he was supposed to testify before. Eventually, the Commission's view prevailed, as they were able to muster evidence of the steel shortage, and Higgins' conspiracy theories proved unfounded.

Preserved Liberty Ship Jeremiah O'Brien

But even as the Higgins contract was cancelled in July of 1942, Liberty Ships were going down the ways in increasing numbers, and for the first time, shipbuilding was very nearly equal to losses. By September, the shipbuilders began to pull decisively ahead, and with the exception of November, they would never again be beaten by the ships being sunk. We'll take a look at how this happened next time.

1 Throughout this post, I'm going to use tons to refer to deadweight tons, the cargo capacity of the ships in question. Other tonnages are available. ⇑

Comments

Are the loss numbers you are comparing new construction to US flagged losses or total losses?

I believe that's total, not just US-flagged.

That's a long shaft. Do you know if there was ever consideration given to turboelectric drive, like the T2 tankers? Or was having an existing design with universal tech more important?

I'm curious what changes were made to the original design, which obviously wouldn't have been optimized for that scale of production.

Engines-amidship was standard for cargo ships at the time, for reasons I can't remember offhand. So the shaft was completely bog-standard practice. I don't think TE was ever seriously considered, probably because it wasn't necessary and would have been a serious bottleneck in its own right.

As for design changes, it was just lots of minor stuff. Redrawing the plans for American practice, cutting down the number of different thicknesses of steel used, some tweaks to support welding rather than riveting.

Another example of part of the US Way Of War. Which is to bury our opponents in logistics.

The other part is "by making science fiction, science fact". A prominent example of the latter is the VT fuse.

It looks like having the engine amidships makes cargo holds, funnel routing, and a bunch of other stuff much simpler.

BTW, do you know if they were building new 3"/50 guns for liberty ships, or if they were all WWI vintage stuff from storage, along with the 4" deck guns? Assuming they were just armed with whatever was laying around, until they finally had enough 5"/38s to start sticking them on shopping carts.

The 3"/50 is an amazing weapon system; introduced before WW1, it held on in US service in various Marks and Mods until the 1990s and is still serving in some countries around the world. Not sure if there's anything like it in history of naval guns (think some Days of Sail cannon had lifespans in a similar range, but only if they didn't burst?).

The liberty ship was a design study in my undergraduate engineering. Sadly it was a study of the things that went badly wrong with it.

Though it was taken as read that the new design and construction method (especially mass use of welding instead of riveting) did result in huge production speed increases.

But then we spent the rest of the time looking at how, for example, the use of welding led to entire ships cracking in half, including at sea.

We didn't, as first year students, then look at the more high level view of increased loses from structural failure balanced against decreased military loses because of increased transport ability. As an engineer with a much more high level view of things these days I see that this is what is REALLY interesting.

Actually, both sides are really interesting, and both should be included in an engineering course. Probably with the second study in 3rd or 4th year to balance out the structural failure study from 1st year.

It's worth pointing out that one feature of the use of different production methods (eg. welding, larger castings, different materials) is that this enabled the use of workers (OK. WorkMEN) from different industries.

These were guys who had never built ships before in their lives, and were pulled from whatever was no longer considered necessary industries and put to work on shipbuilding.

Hey: Secret code to post was 1941.

@Ian

This series was definitely written as a tribute to that American Way of War.

@echo

3"/50 production continued throughout the war. There weren't enough guns in storage.

@Blackshoe

There was a substantial discontinuity in the design in the 1945-1950 period. The Mk 21/22 had a monobloc barrel instead of the built-up barrel of earlier models, while the breech mechanism was changed postwar for the version that survives today.

@Doctorpat

I talk about that some in today's post. I don't think it's even faintly disputable that the risks taken with the design were good ones, and the problems were mitigated pretty quickly. As for workers, a fair number of the welders were women. I didn't dwell on it much (I'm sure someone else has done so at great length) but "Wendy the Welder" made a substantial contribution to shipbuilding.

US labor controls weren't really good enough for that. It was some combination of production controls and the shipyards offering good wages. My great-grandfather went from Oklahoma to Mare Island, where I believe he was a welder. (But not on Liberty Ships.)

If you want more details on this than any human could possibly care about, Ships for Victory gives an incredibly detailed portrait of the building program as a whole. I ignored so many chapters to keep this reasonably coherent.

why on earth would you give them 1 3" gun and 1 5" gun? that seems awful.

They're armed merchants, not proper warships: weight spent on weapons is weight not available for cargo. I vaguely remember reading that the larger gun is on the stern so it can be used while running away.

Basically, the point of the armament on a Liberty Ship (or any WWII merchie) is to (a) keep airplanes at a distance and distract them so they can't bomb as accurately, (b) make sure that U-boats can't attack on the surface and have to use torpedoes and (c) drive up the size of an effective surface raider. A 3" and a 5", with some 20mm guns to supplement, do that just fine.

I get why they'd want 2 guns but why not 2 of the same gun and simplify training/ammo supply?

Because the guns were for two different roles. The 5" gun was primarily for surface targets. The 5"/38 was a great weapon for AA use, but only if it had power operation and directors. The merchant mounts didn't. For AA use, the 3"/50 is a better option, as you're basically just trying to put as many bangs in the sky as you can in vaguely the direction of the enemy, and the lighter 3"/50 can do that a lot faster than the 5"/38 can in a mount without power hoists and fuze-setters. Naveweaps says 12-15 rounds/min for the 5"/38 in that condition and 15-20 for the 3"/50. Also, they really were that short on 5"/38s. Remember how many of the DEs ended up with 3"/50s despite them wanting 5"/38s.

I think most liberty ships ended up with the 4"/50s pulled from WWI destroyers rather than a 5" (although there probably weren't even enough of those, despite having over 1k from the Wickes and Clemsons alone?)

What really astonished me is how fast they started making enough 20mm guns to start slapping them on freighters.

A little off topic, but were the 3" and 40s on DEs all manual follow-the-pointer? I remember seeing some were upgraded with remote power post-war Obvs the armed merch ships were just full manual--wonder if there's any records of them shooting something down.

These were guys who had never built ships before in their lives, and were pulled from whatever was no longer considered necessary industries and put to work on shipbuilding.

US labor controls weren’t really good enough for that. It was some combination of production controls and the shipyards offering good wages.

Yes, I didn't mean that this was an explicit matter of people being told what to do, rather that the economic incentives (and patriotism) was moving people from peacetime industry to wartime ones.

The USN estimated 200 aircraft shot down to 49 ships sunk by aircraft, out of 5300+ US armed merchant ships.

@echo

I have surprisingly little information on the Liberty Ships in general in service. Plenty on the construction program, but not so much on the operational side. So you're probably right, but I'm not really sure.

As for FC on the DEs, the Buckley class had manually-operated 3" guns with a Mk 51 and a 2.5 m rangefinder providing data to the operators, which sounds an awful lot like follow-the-pointer operation. The AA mount (40 mm or 1.1") had a second Mk 51 and power operation.

It's weird, probably more than a quarter million men served on them, but there's so few stories or autobiographies about it. I guess it was just very, very boring most of the time, and a lot of the guys for whom it wasn't never got a chance to tell anyone about it.

It's not so much that there's no autobiographies. There are a few, but that's not really what I'm looking for. I would have liked a lot more detail about the process of moving cargo around during the war. How the ships were armed, how the convoys were planned, etc. I have some of this, but it's really spread out, and didn't fit well here.