The six months after the Fall of Poland in October 1939 were known as the phony war or sitzkrieg, as both sides sized each other up. The first crack in this came in early April, when the Germans invaded neutral Denmark1 and Norway, driven by a combination of Hitler's paranoia about the Norwegians cooperating with the British and a real Allied plan to intervene in Norway to stop the flow of iron ore to Germany. Despite several warnings, both the Allies and the Norwegians themselves were unaware of the coming invasion, and the Norwegian military was still badly hamstrung by low budgets and a lack of manpower.

The German invasion plan

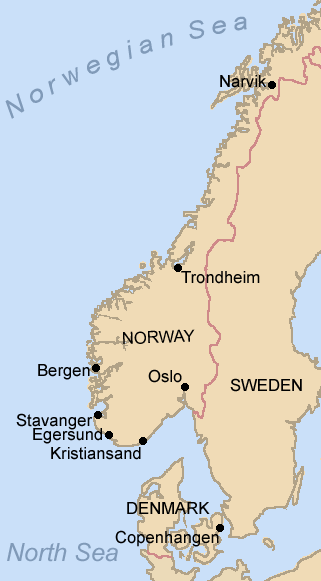

The German plan involved seizing the key cities of Norway: Narvik, Trondheim, Bergen, Kristiansand and Oslo, using troops carried aboard warships. The Germans generally didn't think the Norwegians would fight much, and if they did, their low readiness would let the prepared German troops win despite lack of numbers or specialized amphibious shipping. Follow-on units would be available almost immediately thanks to merchant ships that had been sent out before the faster warships departed Germany. Surprisingly, despite some of the transports passing through Norwegian coastal waters, security held.

Loading of the assault troops began on April 6th, when troops from the 3rd Mountain Division began to board the vessels that would take them to Narvik and Trondheim. This unit had been part of the Austrian army before the Anschluss, and few of the men had ever even seen the sea, much less been aboard a ship. Now, one regiment would be crammed aboard the ten destroyers of Group I, bound for Narvik, while the other would be carried to Trondheim by Group II, the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers. Battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau would provided heavy cover against a British intervention. Unsurprisingly, the warships made poor transports when asked to carry troops equivalent to two-thirds of their regular crew, as well as all of their equipment. As much ammunition as possible was crammed into the magazines, with the leftovers going wherever there was space, and the larger equipment was lashed down on deck. The troops were told to keep below deck while within sight of land or while under attack to avoid giving the plan away, while crews remained at their stations because there wasn't room for them in the living quarters.

Mountain troops go aboard Admiral Hipper for Trondheim

As Groups I and II headed northwards on the 7th, they briefly came under ineffective attack from British bombers. However, the weather soon became both ally and enemy in their attempt to cross into the Norwegian Sea unmolested. A low-pressure system moved in, bringing with it low clouds and strong winds. The clouds made detection less likely, but the wind soon produced heavy seas, which mercilessly battered the German destroyers, whose designers had sacrificed seaworthiness in the quest for speed and firepower. Even with constant maneuvering to meet the seas, the ships rolled 45° and more, and water washed over the deck, often going down the ventilator intakes and knocking electrical systems offline. One destroyer even had a boiler extinguished due to flooding, and even the much larger Hipper had problems, the chief engineering asking if use of the rudder could be limited due to overheating in the steering engine. Despite the conditions, which washed at least 10 men over the side, the group maintained 20 kts, even as the destroyers rolled 45°, throwing the mountain troops below deck around.

Konigsberg

Group III, bound for Bergen, had in many ways the most difficult task. Their objective was only 8 or 9 hours steaming from Scapa Flow and the British Home Fleet, while they would need 24 hours to reach it from Wilhelmshaven. Despite this, it was lightly equipped, with 1900 men embarked aboard light cruisers Koln and Konigsberg, two torpedo boats and a pair of auxiliaries, which kept the group from reaching 20 kts. Group IV, targeted on Kristiansand, had another light cruisers, Karlsruhe, along with three torpedo boats and another auxiliary. The last of the western groups was Group VI, four minesweepers with 150 men of a bicycle reconnaissance company between them, headed for the cable station at Egersund.

Oslo would be the destination of Group V, headed by the new heavy cruiser Blucher, sister to Hipper. Blucher had left the yard only a week prior to the invasion, and she was far from fully combat-ready. Originally, the panzerschiffe Lutzow had been intended to lead the Oslo group, but Admiral Raeder, head of the Kriegsmarine, had wanted to send her into the Atlantic, so Blucher had been rushed into service. In the haste to make her operational, her magazines still contained a great deal of practice ammo, preventing her passengers' ordnance from being stored there. She would be joined by the light cruiser Emden, three torpedo boats, and Lutzow, who had suffered technical problems at the last minute and been redirected to the Oslo group, which was thought unlikely to see combat. In total, about 2,600 men were onboard.

HMS Impulsive, one of the destroyers that took part in the mining operation

In the early hours of April 8th two events took place that kicked off hostilities in Norwegian waters. The first was the British finally carrying out their plan to lay minefields and sever the inshore traffic along the Norwegian coast. 324 mines were laid in Vestfjorden, just outside Narvik, and two destroyers remained on-site to warn off passing merchant ships. Two more were dispatched to Bud to lay a decoy field, including using water-filled drums when Norwegian fishing boats could see. The Norwegian Navy quickly responded to both fields, prostesting British actions and requesting that they leave, and even as reports reached Oslo, a note was delivered with the coordinates of both fields, as well as a third that had not been laid at all.

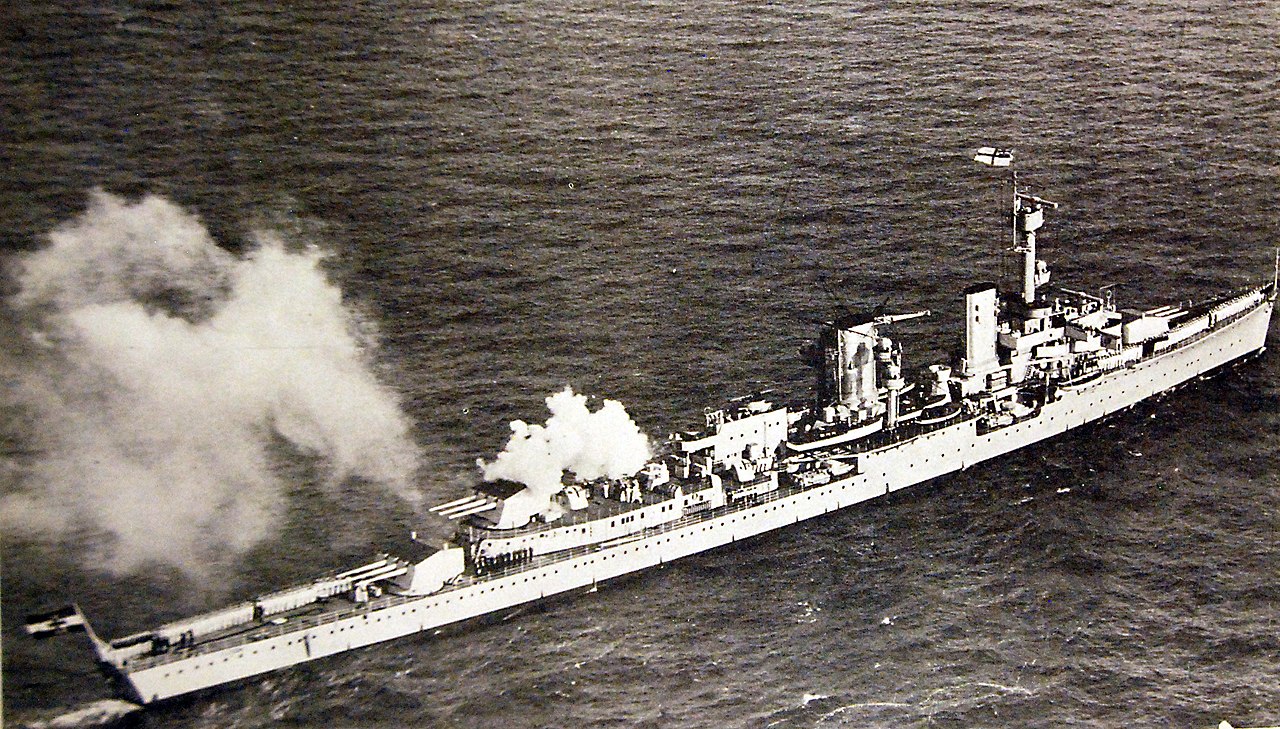

The mining scheme also led to the first proper battle of the campaign. HMS Glowworm had been assigned as an escort to Renown in covering the mining attempt, but had lost a man overboard on the 6th, and had split off to search for him, ultimately unsuccessfully. The worsening weather and navigation difficulties prevented her from rejoining Renown, and she had turned back for Scapa, then been given an updated position and ordered to try again. On the 8th, she was off Trondheim, and despite the heavy weather during the night, hoped to meet the battlecruiser that day. Unfortunately, she was not alone, and soon sighted another destroyer, which claimed to be Swedish. The British captain correctly smelled a rat, and opened fire on one of the German destroyers. That ship escaped, but a second, Arnim, soon appeared out of the mist. Glowworm gave chase, and her superior seaworthiness allowed her to close the gap to her German counterpart. Hipper was ordered to turn back and help, and after some initial confusion over which of the two destroyers was the enemy, she opened fire at around 5 nm.

Glowworm lays smoke as Hipper closes

This was a perilous situation for both vessels. Glowworm was badly outgunned, but her 10 torpedoes were potentially enough to cripple or destroy the heavy cruiser. To mitigate the threat, Hipper’s captain did his best to keep his bow pointed at the British destroyer, while Glowworm laid smoke, a tactic made less effective by German radar. The two ships closed rapidly, with Hipper soon adding her 10.5cm secondary guns and even her 37mm and 20mm AA guns to the battle. After Glowworm’s first salvo of torpedoes missed, some by only a few meters, Hipper turned into the smokescreen, hoping to finish her off before the second could be fired. When she emerged, the two ships were right on top of each other, and despite the best efforts of Hipper’s officers, Glowworm rammed her just abaft the anchor, tearing a 35 meter dent down the starboard side and letting in 500 tons of water. The destroyer's bow was completely gone, and she was left a burning wreck, which her crew soon abandoned. 40 of them were saved by Hipper, although only one officer, leaving the decisions taken aboard her shrouded in mystery.

Glowworm had passed news of the encounter to the Admiralty before she went down, but despite the number of British ships at sea that day, she was the only one to encounter the Germans. The Home Fleet had sailed on the 7th, but was well to the south of Groups I and II and headed north, taking it out of position to stop any of the German groups, while the force that had laid the minefield in Vestfjorden was perfectly placed to thwart the attack on Narvik, but for some reason was ordered out to sea by the Admiralty from shore, allowing the destroyers of Group I to sneak past, now rolling even more heavily as they burned off fuel. A British cruiser squadron came within 60 miles of Group III, but the Germans went unnoticed in the storm, while air reconnaissance spotted Hipper while she and her consorts waited off Trondheim, but no action was taken. Even more puzzling was the decision of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, to disembark the troops which had been loaded aboard the 1st Cruiser Squadron to preempt any German response to the minelaying. This would have grave consequences in the days to come, denying the British troops on the ground right when they were needed the most.

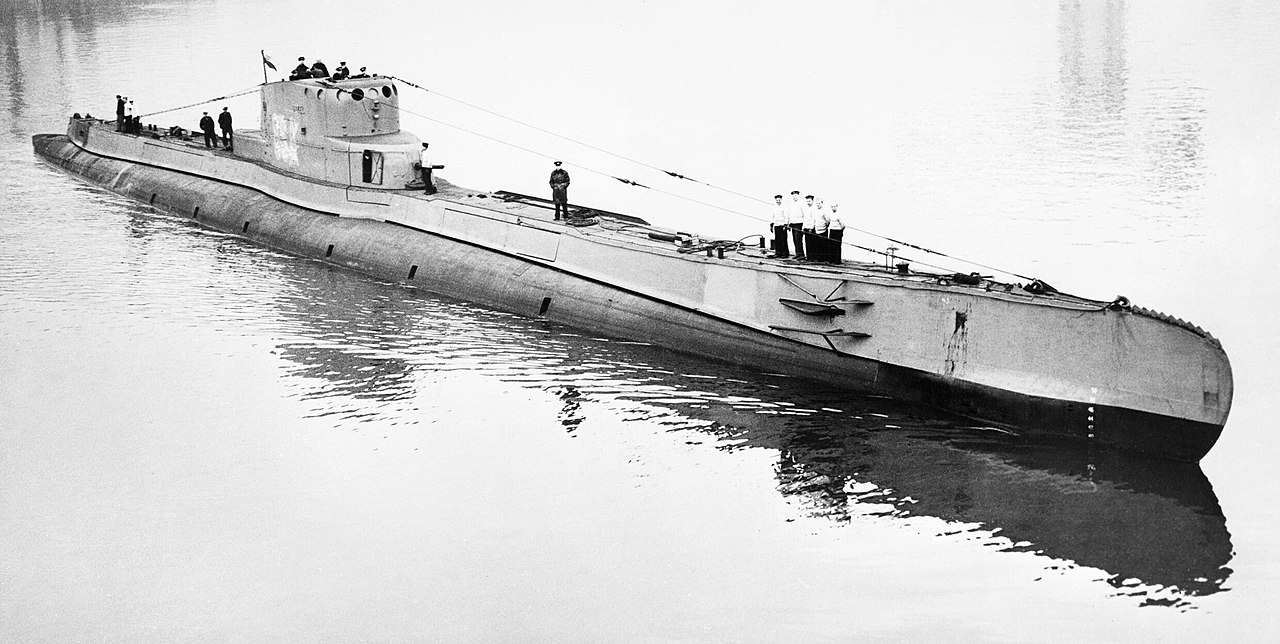

Orzel

The only bright spot for the Allies took place far to the south. They had sent a number of submarines into the North and Norwegian seas to cover their minelaying operations, among them the Polish Orzel. She happened across the German Rio de Janeiro, bound for Bergen with supplies and equipment for Group III and just over 3 miles off the coast of Norway. Her ownership and purpose weren't obvious, and Orzel's captain chose to surface and order her to heave to. The Germans initially refused and tried to run, but the Polish submarine was faster, and eventually torpedoed her. Rio de Janeiro sank, leaving almost 200 survivors, many armed and in Wehrmacht uniforms. Several admitted their mission when questioned, but when passed along, this information made no impression on the Norwegian government, who had become preoccupied with the British minefields. Even as more reports of the imminent threat came in from a number of sources, Defense Minister Birger Ljungberg seemed more interested in the cost of a mobilization than anything else, and no firm decision appears to have been taken. Norwegians went to sleep on April 8th still at peace, but would awake to find their country at war.

1 Denmark was primarily invaded to support the operations in Norway. Because of the nation's inability to effectively oppose the invasion, Denmark surrendered within a couple of hours. I'm not going to go into details. ⇑

Comments

I take issue with your last sentence. I haven't looked it up, but I am pretty sure offensive mine laying is an act of war.

Also, I love how indignant you are that this half baked plan worked as well as it did.

So the Norwegians did have some indications before that invasion that something was going on, but weren't able to consolidate that into a coherent view of what was going on. Is that the usual pattern in situations like this?

@ike

Offensive minelaying is ambiguously an act of war. The Norwegians could have easily chosen not to interpret it as one, because nobody actually got hurt. What the Germans did is not ambiguous, and in that case, you basically either go to war or surrender.

@Johan

It's essentially impossible to maintain such tight OpSec that nobody on the other side knows anything that will point to an operation like this, leaving people after the fact to point out that they should have known. I tend to error on the side of charity, as intelligence work is hard. This case is unusual in how much warning Norway got, and subsequently managed to completely ignore.

Oh, I don't deny Germany planned to make war on Norway the next day. (assuming they kept to international waters; pre-positioning your invasion fleet would probably strain 'innocent passage' a bit.)

"and two destroyers remained on-site to warn off passing merchant ships." and presumably chase off / sunk any Norwegian mine-sweepers

Even despite the minelaying, relations with the Norwegians were relatively cordial, and I really doubt they would have sunk a minesweeper. The point was to disrupt coastal traffic, not provoke Norway into declaring war. Coastal traffic is disrupted even if the minesweepers have gone to work, and at least one of the fields (although it may have been the dummy) was turned over to the Norwegians to guard.

Maybe I am missing something, but this is the impression I get from reading the previous articles. The mine-laying would force Norwegian-flagged shipping (from Narvik) into international waters where it would be subject to capture by the Royal Navy.

I'm not sure exactly whose flag the cargo ships were under. I know that most of the large Norwegian Merchant Marine had already been chartered by the British, so I suspect that most of the ships carrying ore were German-flagged. (Particularly as Germany had little use for them otherwise.) It is possible that the Norwegian-flagged ships that were carrying ore to the Germans would have been seized, but in general the threat of doing that was enough to keep merchant ships at home.

I find it impressive that the Germans invaded Denmark to make it easy to invade Norway to make it easy to control Sweden, which was their actual target.

Impressive is not really the right word, but something like that.

I've just been reading The Gathering Storm, in which Churchill discusses this episode, though generally in less detail.

The impression I get is that the British treated this as an incipient fleet action, with the invasion of Norway just a sideshow. So the First Cruiser Squadron put its soldiers ashore on the night of April 7, so it would be ready to join the fight without worrying about stray passengers; and a naval attack on Trondheim was postponed because they'd lost track of the German battlecruisers, and thought dispatching a force for this purpose would leave themselves vulnerably dispersed. British plans to occupy the Norwegian ports were, per a War Cabinet meeting on April 9, "not however [to] move until the naval situation had been cleared up".

The British win if they either control (northern) Norwegian soil, or if they control Norwegian waters. The Germans have to control both or the ore doesn't reach Germany. The British having a powerful navy and a weak army, it was sensible for them to treat this as a mostly naval problem.

They failed, in part because Germany was able to surge what fleet they had before the Allies were able to react properly, in part because Norway was barely an ally, and in part because the rapid fall of Denmark blocked the Royal Navy's access to the southern Norwegian coast. Putting a few more British soldiers into northern Norway before being forced to withdraw, wasn't going to help matters.

One of the things I've changed my mind about in the last few years (thanks to some of the books I've read) is how we have to change how we think about perceptions of WW2 from before WW2; one of these is that from the knowledge they had at the time, the isolationist viewpoint in the US is pretty reasonable up until Dec 7th, 1941. The preliminaries of the Norwegian campaign really do seem a lot like the pure great power politics of pre-WW1.

BTBT there's a Danish movie called April 9th about the invasion by Germany that I can recommend if you're interested and have a couple hours to kill. Spoiler Alert: it doesn't have a happy ending.

One of the things I've changed my mind about in the last few years (thanks to some of the books I've read) is how we have to change how we think about perceptions of WW2 from before WW2; one of these is that from the knowledge they had at the time, the isolationist viewpoint in the US is pretty reasonable up until Dec 7th, 1941. The preliminaries of the Norwegian campaign really do seem a lot like the pure great power politics of pre-WW1.

BTBT there's a Danish movie called April 9th about the invasion by Germany that I can recommend if you're interested and have a couple hours to kill. Spoiler Alert: it doesn't have a happy ending.