By 1906, the British had developed a system that solved the basic problems of fire control. It would take ranges from the ship's rangefinders and then compute basic corrections for the movement of the target ship, a process known as rangekeeping. The problem was that the central instruments of this system, the Dumaresq and Vickers Clock, were only really suitable for situations where the range rate was low and not changing quickly. Maneuvering targets could throw them off.

Destroyer HMS Salamander at Malta, 1900

The first serious solution came from a man completely lacking in obvious qualifications for the job. Arthur Pollen was neither a naval officer nor an engineer, but when he was invited by his cousin William Goodenough1 to witness gunnery practice at Malta in 1900, he was appalled at what he saw. The maximum range the ships fired at was 1,500 yards, a far cry from the 8,000 yards or more that the same guns were being used at on land in South Africa. When he asked for an explanation, he was told that the problem was the lack of an adequate rangefinder. Pollen was managing director of the Linotype Company and set his engineers working on the problem, initially by analyzing the change of range between two ships steaming on opposite courses.

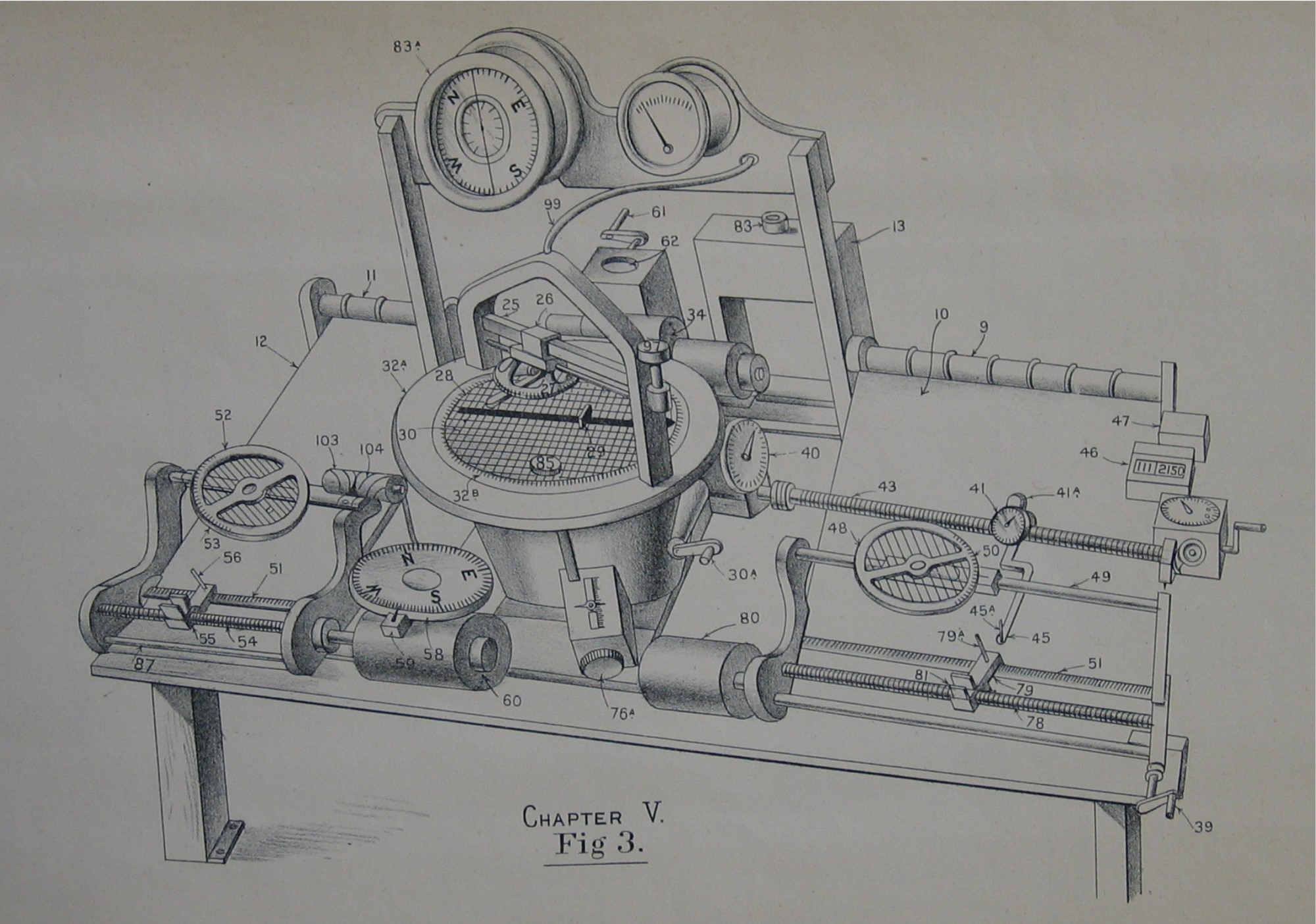

An Argo Clock2

This analysis revealed that the problem ran much deeper than the mere matter of a rangefinder. The range changed at a high and variable rate,3 and Pollen decided that the best way to deal with this problem would to be plot the ranges and bearings to the target, while compensating for the motion of the firing ship. This data could then be used to calculate the course and speed of the target, which would make it easy for to compensate for any changes in the motion of the ship. This method, known as true-course plotting, has many theoretical advantages, but is hard to implement for fire-control purposes, particularly with the technology of the day.4 Another alternative, virtual-course plotting, assumes, much as the Dumaresq does, that the firing ship is stationary, and assigns all motion to the target. Unfortunately, this makes it impossible to disentangle changes in the target's motion from changes in the motion of the firing ship. Worse, neither method was feasible in 1900, as compasses weren't precise enough to tune out the ship's yaw.

Dreyer is on the right in this picture with Jellicoe (center)

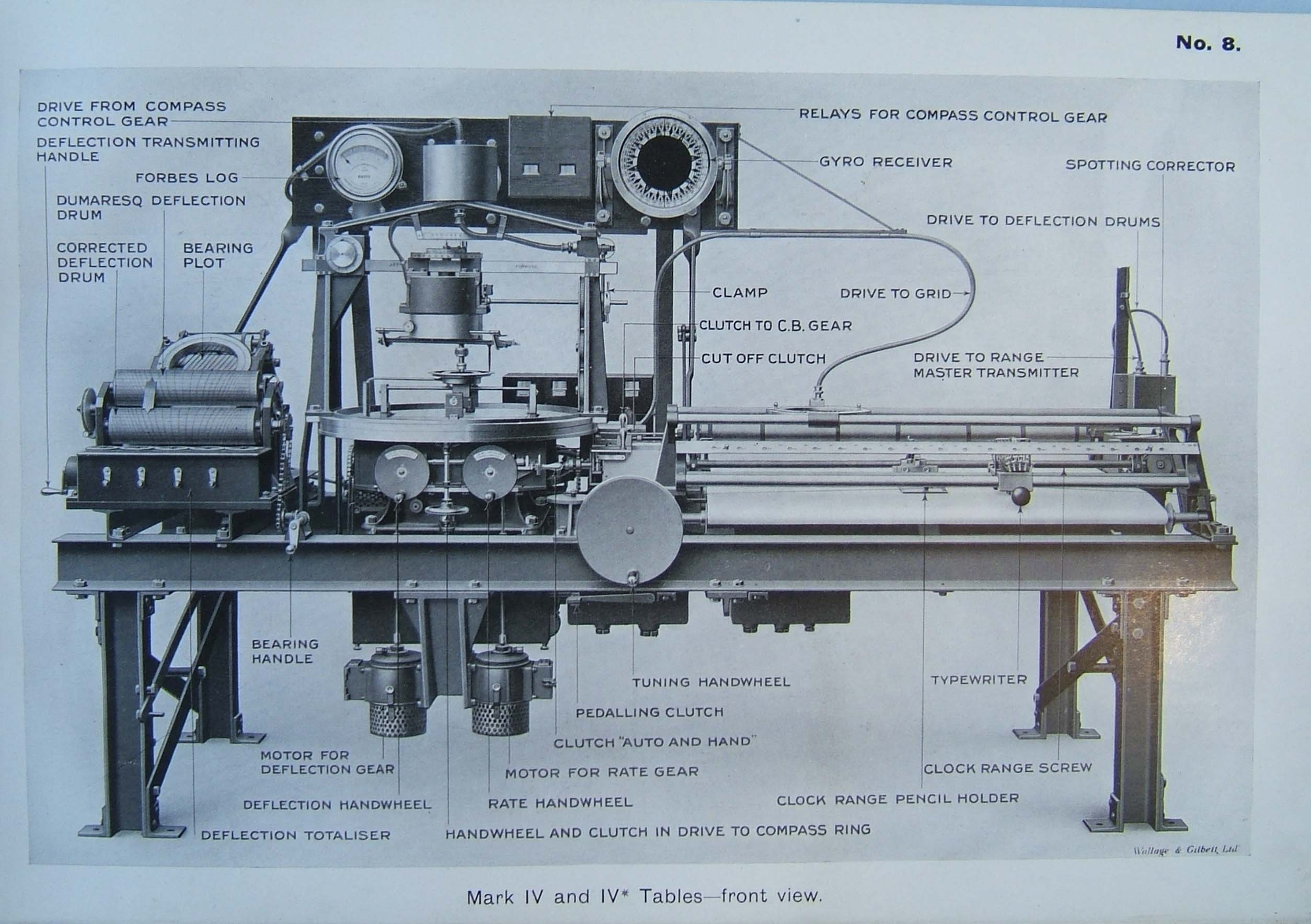

But there was a third option, developed by an RN officer, Frederic Dreyer.5 He realized that, while highly varying range rates were possible, they weren't all that likely in action, and that by simply plotting ranges against time, the range rate could be determined as the slope of the resulting plot. The inevitable errors in the input data could easily be smoothed out by eye, and any spurious data points discarded. This worked with the technology of the day, instead of requiring major advances in gyros to be practical.6 Even when that happened, around 1910, the preference was to add a plot of bearing against time to the existing range plot, instead of switching to true-course plotting. At about that point, Dreyer unified all of the elements developed so far - plots, range clock, Dumaresq and transmitters - and created the eponymous Dreyer Table. This also allowed him to incorporate feedback from the clock onto the plot, as the table automatically drew a line showing the current range. Any deviations between clock range and plot range were easily identified and corrected.

This device brought Dreyer into conflict with Pollen, who had turned his true-course plot into the first synthetic fire-control system. Both range and bearing were tracked directly, although Pollen used the equivalent of a virtual-course plot instead of a true-course plot. To handle changing rates, he had developed an improved version of the integrator that drove the Vickers clock. His did not have any problems with the rate changing while in motion, and it was driven by a device that continually updated the rates as the solution changed. This made it much better at handling situations where the range rate was high and changing, as might be found in a fast-moving battlecruiser action. It also gave greatly improved performance in situations of variable visibility, as the solution updated automatically without regard for visibility. Errors in the solution would become obvious as new information came in from the rangefinders, although Pollen's presentation of these errors was not as effective as Dreyer's. However, the system was complex and expensive, and Pollen made the mistake common to innovators of claiming results that would only be delivered after a great deal of development. During tests, the Dreyer table in the hands of an experienced gunnery officer could usually deliver similar results, and the gunnery officers in question distrusted the complex machinery, believing that humans would be more reliable. Pollen, a lawyer by training, thought that elimination of human error was the way forward, and history would ultimately prove him right.7

In 1907, budget cuts forced abandonment of plans to buy an early version of Pollen's Argo Clocks for half the fleet, and Pollen's habit of making enemies within the Admiralty soon resulted in opinion swinging in favor of Dreyer. By 1912, opinion of Pollen had fallen so far that the Admiralty declined to renew his monopoly agreement, allowing him to sell his system on the global arms market. He sold the system to Russia, and Hannibal Ford developed a very similar system for the USN, to the point that he requested the Navy indemnify him in case of patent disputes. But the RN made the Dreyer Table its standard fire-control system, and it was aboard all but a handful of ships at Jutland, the balance being ships carrying the few Argo clocks the Navy had purchased for trials. The Dreyer Table was improved throughout the war, with new mechanisms being added to streamline data transmission, compensate for the firing ship's turns,8 factor in deviations for wind and drift and even give a limited degree of blind-fire capability. The final version of the table was used aboard Hood until her loss, and the last table in RN service, fitted to the monitor Roberts, wasn't retired until 1965.

HMS Roberts

In the end, the Dreyer analytical system would prove a dead end, and synthetic systems like those pioneered by Pollen would be near-universal by the time WWII began. We'll examine their development next time.

2 Model by Rob Brassington, render from The Dreadnought Project. ⇑

3 Note that this was before Dumaresq invented his eponymous device. ⇑

4 This is the same type of plotting used for navigation and building a tactical picture, but errors and delays there matter much less than they do in fire control. A 1° error at, say, 5,000 yards is equivalent to 262', enough to turn a direct hit on a typical battleship of the day into a miss, but irrelevant for situational awareness. ⇑

5 Dreyer would later become flag captain to Jellicoe at Jutland, and then go on to fix the problems that battle revealed with British shells. ⇑

6 Pollen also did a great deal of work on these gyros, and his stabilized rangefinder, capable of taking accurate bearings and staying on target despite the movement of the firing ship, was bought in large numbers by the RN. ⇑

7 This particular cases is very weird. Usually, when an outside amateur, however smart, comes in with a novel way of looking at things, it's terrible and doesn't work. ⇑

8 This used an early version of an electrical follow-up, with motors to update the range and bearing clocks. If the pointer on the table's Dumaresq was in the right place, all of the circuits were open and the motors were still. As the ship turned, the circuits would close and the motors would turn, updating the values on the clocks until they lined up with the Dumaresq again. ⇑

Comments

So why weren't the British able to cut the Germans to ribbons while staying out of range of the German guns? Did the Germans have their own people doing similar development, or did the British tech leak out to their enemy?

The Germans had their own fire-control system. On technical merits, it was probably worse than the British system, particularly at long range (which the Germans just weren't interested in until around 1913, when British expectations for battle range were actually falling) but the British battlecruisers at Jutland had poor visibility. The main battleship engagement could pretty much be described as "the British cutting the Germans to ribbons", with the Germans running away before they had enough time to cut.

(Seriously, there was so much going on in this era for fire control, and Dreyer/Pollen is only part of it. I could spend months essentially serializing Friedman's Naval Firepower, but I'm not sure that would be fun for anyone. If you want all the gory details, copies aren't that expensive.)

This whole area is fairly invisible to the average person, even the geeky teen into war tech such as I was (once). But it's perhaps one of the most important aspects of 20th-21st century military tech history. Even today, the whole point of the Aegis systems of the USN, or the F35 fighter, is the fire control and associated target plotting. Yet popular accounts still break everything down to top speed, range and the caliber and rate of fire. At which point most decisions don't make sense.

So what I'm saying is that I'm really grateful that you are distilling this for me so I can get the story in between me editing documents about boring stuff like FDA submissions. : )

Thank you. Fire control is one of my favorite things, and the reason it doesn't come up more here is probably related to the reasons it's so often ignored in other accounts. It's really hard to write about in a manner that doesn't turn into a giant pile of incoherent facts. Gun caliber is easy to understand. (I suspect this is why plans for battleship reactivation keep being floated.) The finer details of how a fire control system works? Definitely not, so it's easiest to just skip it.

I think the real reason people talk about battleship reactivation is that they look AWESOME. Those photos of broadsides with the muzzle blast flattening the ocean are just an example.

That's certainly a part of it, although I think it ties closely into my theory. The guns are very cool and sexy, at least partially because they're easy to understand. Picturing a giant cannon firing something the weight of a car at a target is easy. Particularly when the pictures look as good as they do. It doesn't hurt that the Iowas are very photogenic. If they looked like French Pre-Dreads, then we wouldn't have this problem.

They probably had the same problem trying to phase out beautiful, majestic cavalry in favour of smelly, clanky, clumsy tanks.

More or less. I'm obviously a lot less familiar with that, but there were pro-cavalry people as late as WWII. Fortunately for those phasing out the horses, said war gave a pretty good excuse to ignore those people.

Were the cavalry people even wrong in WW2?

Sure, we all love to make fun of Marshal Semyon Budyonny's opposition to Tuchachevsky's tank based reforms, but the Soviets made fairly good use of horse cavalry as late as 1945 against both the Germans and Japanese. They operated within combined arms cavalry mechanized groups as dismounted infantry after the tanks made a breakthrough of the enemy lines. This was especially effective when tanks and trucks bogged down in the mud of the rasputisa, and logistics were unable to bring up the fuel and spare parts that horses did not require. I think the Soviets actually expanded the use of cavalry formations throughout the war, and they proved especially useful in reconnaissance, pursuit, and exploitation roles. The last Soviet horse cavalry formations were only disbanded in 1955.

On the western front, frontage per unit is too low for cavalry to get anything done, but in the vast open steppes of the east, cavalry found a niche defending the motherland. Heck, even legendary tank commander Patton said "had we possessed an American cavalry division with pack artillery in Tunisia and in Sicily, not a German would have escaped."

Source from 1946: http://www.lonesentry.com/articles/cavalry/index.html

I should have known this would happen if I wasn't more careful with my statements.

I was vaguely aware that there was some use of horse cavalry in WWII, besides the famous use of it against armor in Poland (which IIRC didn't actually happen). But it was very much reduced to fringe roles, in the same way that New Jersey found herself reduced to a bombardment platform in Vietnam.

Patton was originally a cavalryman, and I'd take his claims on this with a grain of salt. Or several pounds, in this case.

It didn't happen as usually described, but there was a real event that the story is 'about'. tl;dr Polish cavalry charged at German infantry, successfully, before German armored cars with machine guns came to the rescue.

Yeah. That's what I meant. The Poles didn't charge German tanks, lances or no. I don't have time to be an expert in WWII on land, too.

If my recollection is correct, the story that the Polish cavalry charged tanks (and got slaughtered) was a German propaganda story, that the Germans put in some wartime propaganda movie to show "look how dumb our enemies are".

For some reason this story stuck around even when the Germans lost the war, perhaps because the movie scene was well filmed, and probably helped along because the Poles were now on the other side of the Iron curtain.

"Friedman’s Naval Firepower... If you want all the gory details, copies aren’t that expensive."

1.951,99€ :-O

Copies were not expensive at the time of writing. I've seen this plenty of times. Put a price watch on it, and it will come back down.

Fascinating article. Is there anywhere one can see a Dreyer Table? National Maritime Museum perhaps? Freddie Dreyer was my great grandfather - I never met him sadly

Fascinating article. Is there anywhere one can see a Dreyer Table? National Maritime Museum perhaps? Freddie Dreyer was my great grandfather - I never met him sadly

Fascinating article. Is there anywhere one can see a Dreyer Table? National Maritime Museum perhaps? Freddie Dreyer was my great grandfather - I never met him sadly

Sadly, I doubt that there are any surviving tables. I don't think I've ever seen a modern picture of one, which I would definitely have if one exists. Consider writing to Warship International to check, though. They'd be able to say for sure.

And thanks for dropping by.

Backtracking a bit... "Patton was originally a cavalryman"

That's true, of course. Also Patton was kind of a kook, and definitely erred on the side of romanticizing the past. But AFAIK he did not take that to the point of advocating for the US Army to bring back horse cavalry in preference to motor vehicles, or even as an adjunct to them. By the end of WW1 he seems to have been pretty thoroughly converted to the idea of using tanks to fill the cavalry role, and he spent the next few years figuring out how to make that work.

Note that, assuming the quote above is even Patton's (it might be - see above re: "kook" - but I did not see any mention of him in the article at the link, which discusses Soviet use of horse cavalry during WW2), what it doesn't say is, "The US Army should maintain an entire division of horse cavalry, and sustain all the logistical costs of maintaining such a force overseas, because it could have come in handy in this one niche situation." It doesn't say, "Horse cavalry would have been super useful for operations in Sicily, or Italy, or France, or Germany."

@Philistine

I wasn't able to find my copy of a paper Patton wrote in the 1920s on the subject of horse cavalry, but do recall that he was quite bullish on its prospects for at least the near future.

As late as his 1932 Army War College memorandum The Probable Characteristics of the Next War And the Organization, Tactics, and Equipment Necessary to Meet Them, written when he was a major, he argued:

Aren't cavalrymen, who fight dismounted, instead dragoons?