The British battleships that served during WWII were less homogeneous than those of the US. While the USN had emphasized standardization during the pre-treaty era, the RN had not, and was left with a bizarre mix of ships, made more confusing by refits. 10 battleships1 and 3 battlecruisers2 dating back to WWI made up the bulk of the fleet at the start of the war, accompanied by the two units of the Nelson class built in the 20s under the Washington Naval Treaty. During the war, the 5 units of the King George V class joined the fleet. They were fast battleships of the same type as those built worldwide after 1937.3

HMS King George V

The British battleships fulfilled largely the same roles as their American counterparts, although with less emphasis on carrier screening and more on surface superiority. There were several reasons for this. First, the carrier was less important in the narrow seas around Europe, and the threat of surface forces significantly greater. Second, the British entered the war two years before the US, and that time interval was critical to the development of airplanes that were serious threats to battleships at sea. Third, the lack of an equivalent to Pearl Harbor meant that the British never were forced to radically change their doctrine away from the battleship. All that said, by the end of the war, when the British were operating with the US Pacific Fleet, their ships, battleship and carrier alike, were used very much like their American counterparts.

Warspite in action off Narvik

The war did not begin well for the British battleship force, as one of their number, Royal Oak, was torpedoed while at anchor in Scapa Flow a month and a half after war broke out. The next six months were spent guarding convoys and protecting against the possibility of a German breakout. The first major battleship encounter of the war was the Action off Lofoten, during the opening stages of the Norwegian campaign in April of 1940. HMS Renown engaged the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and forced them to disengage with minimal damage to either side. A few days later, Warspite went into action off Narvik, destroying a group of German destroyers and providing fire support for the landing that retook the town.

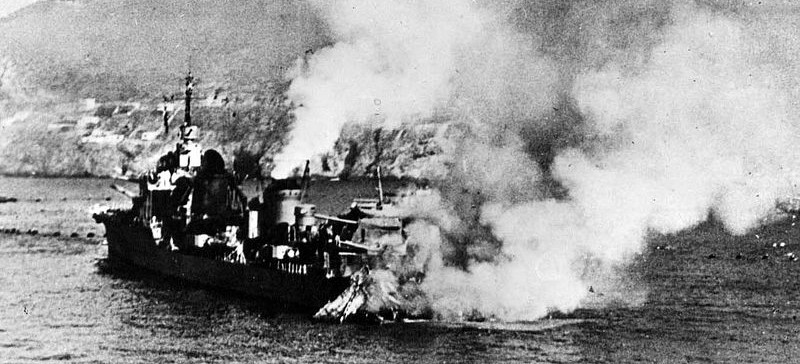

French destroyer Mogador aground off Mers-el-Kebir

A month later, the Germans invaded France. As France collapsed, Italy decided that it wanted some of the spoils, opening the war in the Mediterranean. This was a strategic disaster for the British, drawing most of the British fleet not required to keep the Germans pinned down. The biggest concern was the fate of the French Fleet, the second-largest in Europe. Much of it had fled France to Mers-el-Kebir in what is now Algeria, and when the commander refused to either hand over the ships to the British or rejoin the war, they began a bombardment of the port with three battleships. It was not particularly successful, sinking one of the four French battleships and temporarily disabling two others, but bringing Britain to the verge of war with France. A few months later, a similar attempt on the French fleet in Dakar, Senegal was much less successful, with the French taking only light damage and the battleship Resolution nearly being sunk by a submarine.

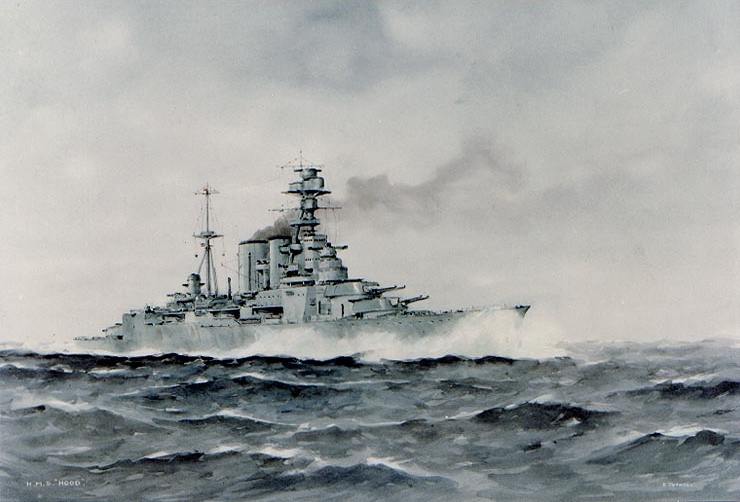

HMS Hood

Six days after Mers-el-Kebir, the British and Italian fleets clashed off Calabria, as both countries were attempting to run convoys through the central Mediterranean. The resulting battle, between two Italian and three British battleships, was inconclusive, except for one of the longest-range hits in the history of naval gunnery, on Giulio Cesare by Warspite. Another indecisive action between the opposing battleships followed that November off Cape Spartivento.

Warspite

In March of 1941, the Italian fleet came out again, in an attempt to interdict British convoys carrying troops to the fighting in Greece. The Battle of Cape Matapan saw an initial cruiser action, after which the Italians started to run for home. Admiral Andrew Cunningham slowed them with airstrikes, managing to cripple the cruiser Pola. Two other cruisers turned back to aid her, and in a brilliant night action, all three were sunk by Warspite's gunfire, along with two destroyers. Unfortunately, the British then lost track of each other and had to disengage, allowing the rest of the Italian force to escape.

The last photo of Hood before her loss

May was a busy month for the British surface forces. In the Med, the evacuation of Crete saw Valiant and Warspite damaged, while Bismarck began her famous Atlantic cruise. In the Denmark Strait,4 she was met by Hood and Prince of Wales. Their clash is the stuff of naval legend. Less than 10 minutes into the action, Hood's magazines were set off by a single shell from Bismarck, leaving only three survivors.5 Prince of Wales fought on, until teething problems with her turrets forced her to break off. However, she landed two hits that forced the German ship to head for France.

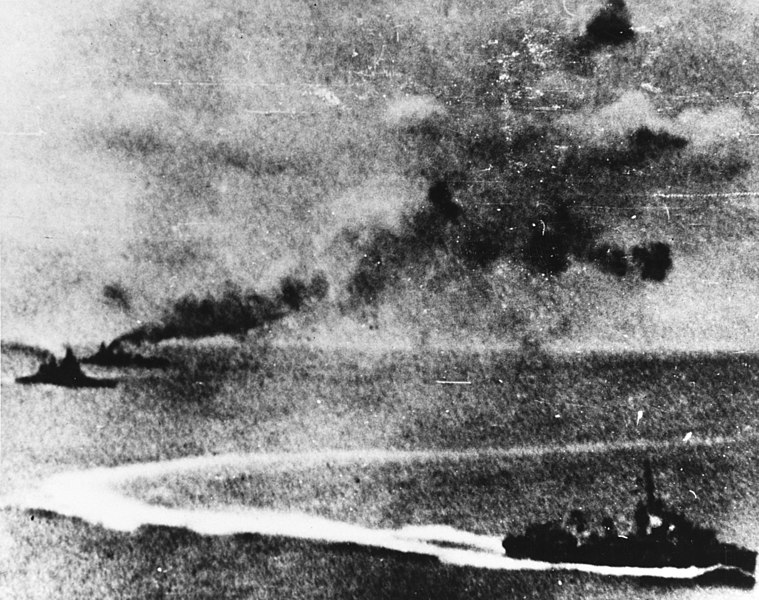

Bismarck burning amid shell splashes

Two days later, an airstrike from the carrier Ark Royal scored several torpedo hits on Bismarck, jamming her rudder and giving the other pursuers a chance to catch up. The next morning, the battleships Rodney and King George V closed to gun range and pounded Bismarck into scrap. Finally, Bismarck was torpedoed and settled to the bottom of the Atlantic.6

Prince of Wales and Repulse under air attack, with an escorting destroyer in the foreground

The second half of 1941 was not easy for the British capital ships. Nelson was torpedoed covering a convoy to Malta, while Barham was lost off Egypt to a U-boat. Queen Elizabeth and Valiant were attacked by Italian frogmen and took heavy damage. Repulse and Prince of Wales were sent to Singapore in December, and sunk while trying to attack the Japanese invasion fleet. The surviving R class had already been dispatched to the Eastern Fleet in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), although the Japanese were more interested in the Pacific, and they never had to fight.

HMS Rodney

Starting in late 1941, the battleships of Home Fleet took on the responsibility of covering the Arctic convoys to Russia against German surface forces. Most of the time, this was boring duty, as the Germans concentrated their air and submarine attacks on the merchant ships, not the distant covering force. Only once, at the Battle of the North Cape, did they have to fight. Duke of York sunk Scharnhorst in the last big-gun duel fought by a British battleship.

Duke of York's gun crew after North Cape

Besides their surface-superiority role, the British battleships did extensive shore-bombardment work. Revenge bombarded Cherbourg in 1940 to disrupt German invasion preparations, and various battleships provided support to operations in Northeast Africa. In early 1941, Operation Grog saw them bombard Genoa, sinking four ships and evading all Italian responses. Later that year, a major bombardment of Tripoli was mounted in an attempt to interdict supplies to Rommel, although dust meant it was ineffective.

Warspite bombarding Sicily

Ramillies provided bombardment support for the invasion of Madagascar, a pattern that was repeated as British battleships provided cover and bombardment support for invasions around the world, including North Africa and Sicily. Off Salerno, Italy, Warspite was hit by a German guided bomb and badly damaged. She was only partially repaired before she and Ramillies covered the Normandy landings. In the Pacific, Renown, Queen Elizabeth and Valiant bombarded Sumatra.

Warspite supporting the Normandy landings

British battleships covered carrier forces and were covered by carrier forces throughout the war, but as the war in Europe wound down, the British began to put together their contribution to the Fast Carrier Task Force. This operated much like an American task force, with the fast battleships screening the carriers from the heavy Kamikaze attacks. King George V even joined the American battleships for a pair of bombardments of the Japanese mainland.

British and American battleships in Sagami Wan just before the surrender

The British capital ships did a tremendous and difficult job, holding the line against the Axis alone throughout the first half of the war. It's a tragedy that none of them are preserved today, primarily because of the economic crisis that gripped Britain in the war's aftermath.

1 There were five units of the Queen Elizabeth class and five of the Revenge class. Three of the Queen Elizabeths were refitted extensively in the 30s, and were part of the first line at the start of the war. The Rs were slower and hadn’t been maintained as well. ⇑

2 Renown had gotten a refit like the three QEs, while Repulse was unmodernized. Hood, basically a 30 kt Queen Elizabeth, hadn’t been either. ⇑

3 They built another fast battleship, HMS Vanguard, using spare 15" turrets from WWI. She wasn’t commissioned until just after the war ended, and is thus excluded from this post. ⇑

4 Which is between Iceland and Greenland, and nowhere near Denmark. ⇑

5 Contrary to popular belief, this was not because Hood was a lightly-armored battlecruiser. |Her armor was comparable to the QEs and Rs, and their captains were warned that they were similarly vulnerable immediately after she was sunk. ⇑

6 There's an interminable and stupid debate over what actually sank Bismarck, with some Nazi fanboys claiming that she was scuttled. It's probably technically true that the scuttling charges were the final straw in actually moving Bismarck below the surface, but she had been totally disabled by the British long before, and they deserve full credit for sinking her. ⇑

Comments

Nit: Forced the German ship to head for a friendly port, of which there were several available. I think I've argued before that France was probably the worst possible choice, and that this was knowable at the time.

I don't remember that argument. France was the closest to the Atlantic, and the only one that didn't have a strong British chokepoint waiting for them. At this point, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were in Brest, and there were repair facilities there. St Nazaire hadn't even been raided, so I'm not seeing the downside except British air attack, and that didn't get bad until later.

Bergen was closer, with much less of the Royal Navy positioned in between, and from there a quick refueling and on to Kiel. Once you're clear that Operation Rheinubung is off, and particularly with three fast, radar-equipped cruisers shadowing the force, the priority should have been the quickest possible return to the safest and most capable possible repair site. And once you're clear that Operation Rheinubung is off, you finish off the Prince of Wales and retain Bismark's reputation as a mythically invincible ubership - mostly undeserved, but nobody needs to know that.

You can make another dash into the Atlantic later, when damage is repaired and when the British don't know exactly where you are and where you are going.

This proposal requires the Germans to be sensible. At sea, that's a very tall order.

Even leaving that aside, it's not necessarily that terrible of a plan. France has good repair facilities, and isn't that much further than Bergen if you chose to go back through the Denmark Strait. If you go south of Iceland, you're asking for a meeting with Home Fleet.

Other German surface ships had operated successfully in the Atlantic (to the extent that they weren't sunk, at least) in the face of British hunters, and it wasn't immediately obvious that Bismarck would be an exception. Turning back after sinking Hood and driving PoW off means that you're admitting defeat. Remember that the cruisers lost her and she was only reacquired after inappropriate use of the radio. In fact, the British were apparently operating under the assumption that the Germans were trying to return to the North Sea before that transmission. And British sea surveillance was only going to get more effective as the war went on, although they might not have known that.

The Germans, in all domains of the war, seem to have had reasonably good tactical execution/training and at least in the early phases of the war better technology, but absolutely terrible strategic vision.

How much this ultimately mattered in the end, versus more intrinsic (for want of a better word) qualities of the combatants (in terms of population/economic output/geography) is not something I'm fully qualified to opine on, but it seems to be a recurring theme in most histories of the war.

One of the things that amazes me about WWII is how effective the Allies were at repairing their ships and returning them to battle if at all possible. The various Pearl Harbor salvages are the foremost examples, but there are scores of others, from the Enterprise on down. I wonder how relevant that capability would be going forwards, or if the existing ships are too complicated to meaningfully repair over a useful timeline.

Depends on the damage. If it's minor metalwork, then yes. But if it's serious damage to the electronics, then no. It's probably cheaper and easier to scrap the ship and build a new one.

In the face of generic British hunters. Not, I think, when being shadowed by fast, radar-equipped cruisers.

And if you go out into the North Atlantic, you're pretty much guaranteed such a meeting, because the Home Fleet has been sent to cut off your advance and see above.

Sinking one of the Royal Navy's most powerful battleships and crippling another, then saying "I'm going to need some more fuel and ammunition before going up against the rest of them", looks very little like a defeat. Also, turning back means you don't have to settle for driving PoW off; you can go ahead and sink her. That looks not at all like a defeat.

You're right that if this had dragged into 1942, British surveillance would have improved. But if this had dragged into 1942, Bismark's consorts on her next sortie would have been, A: Tirpitz and B: their joint reputation (in Berlin and London) for mythic invincibility. The value of the German surface raiders was never in the tonnage they would sink; U-boats and Condors were more efficient in that regard. What happens to the convoy system when even a (single) battleship escort seems insufficient?

How much did the Germans know they were being shadowed by said "fast, radar-equipped cruisers"? I genuinely don't know, either their general knowledge of British radar at the time, or their specific thoughts on this case. Note that Prinz Eugen got to Brest without trouble.

Given that the British wouldn't have caught them if not for an antique biplane torpedo bomber, that seems a bit strong. And that biplane wasn't seen as much of a risk, due to some appalling applications of probability theory by the German commanders.

Very few convoys had battleships in this timeframe, and the British were actually outbuilding the Germans. (Duke of York, Anson, and Howe all commissioned in 1942.) I'm not as certain as you are that Bismarck would have gotten PoW without taking damage that would be ultimately fatal, either. A few more hits, and the rest of Home Fleet becomes a serious threat.

I appreciate the note about who actually sank the Bismarck. If the British don't get the credit for her sinking, then the Japanese won the Battle of Midway 1-0. All the Japanese carriers were scuttled, while the Yorktown was sunk by the Japanese outright.

Speaking of Howe, do you the name changed because Beatty's legacy fell out of favor?

*"do you think", derp.

And the same for Jellicoe-->Anson. Maybe nobody wanted to think too hard about Jutland?

AIUI (and it's been a while since I looked into this), it was mostly because there was still a bit too much politics hanging over the whole thing, and they went with less controversial choices. But I'd have to do some digging, and I don't have time right now.

I have to quibble with the opening sentence “ The British battleships that served during WWII were less homogeneous than those of the US.”

The US had Arkansas a 1 ship class by this point because her sister had been converted to a training ship with 12” guns. The two New York's with 14” guns all of which were decidedly second line and certainly inferior to even the worst British ship the R class.

Then we get Nevada and Oklahoma the first of the “standard type” By the time WWII breaks out Oklahoma was more a liability than an asset with her triple expansion engines limiting her speed significantly. After that the designs get much more harmonious with all but one class having 12 14” guns before the Colorado goes to 8 16”. That being said the differences between a Colorado and say Arizona are easily in line with a modernized and unmodernized QE.

The USN builds three classes of fast battleships with one being 6 knots faster than the other two.

So let’s breakdown the US fleet.

4 ships in three classes are essentially unfit for any kind of frontline service.

You then have the remainder of the standards which while having certain characteristics in common are far from a homogeneous lot. Nevada is at best equal to an R class and at the top the Colorado’s are slower than the QEs but better armed and protected. I’d rate them equal to the fully modernized QE’s at the outset of the war.

Then two classes of 28 knot fast battleships and one class of 33 knot ships.

The Brits have the R’s which are pretty homogeneous and while on the slow side faster than the US ships and well armed.

The QE’s are essentially in two groups between modernized and unmodernized ships though the central difference is in AA firepower not their main battery’s or protection. Yes there are differences but there not huge.

The Nelsons are 16” armed more modern but still on the slow side but at least they and the QEs are comparable in terms of speed.

Then you have the BCs with one being fully updated and another one though unmodernized equivalent to a fast battleship in speed and protection in most regards. Then finally the new fast 14” ships.

Back on the US side when war breaks out things really start changing after Pearl Harbor. Some ships like Colorado get minimal refits and fight the war almost unchanged. Others like Nevada and Pennsylvania get mid level upgrades with all new Secondary suites that vastly improve their AA firepower but not a lot else. At the top are ships like West Virginia which are fully rebuilt to a standard that the USN believes makes them virtually equal to a new fast battleship in every aspect except speed. The differences in those ships shows up strongly at Suriago Strait when the ships with fully updated fire control systems can achieve first Salvo hits while the ships with older systems have real trouble engaging at all.

In my view at the outset of the war the US and the UK had similar levels of diversity in their battleships. But I think by wars end the differences are actually far greater on the US side than the UK side.

Just a quibble on an excellent article.

I do think the statement is true, in that the US has essentially three groups (very old, Standard, and fast) while the British require a lot more buckets to classify. But that aside, the first and last paragraphs often get a bit more poetic license than the rest of the post because I need on and offramps for the reader, and those are vastly easier to write if I'm not super-pedantic.