Last time, we discussed multihulls, the catamarans and trimarans that are make up a small but significant portion of the world's fleet. Most multihulls are designed primarily for high speed, but for high speed to be useful, it needs to be practical if the sea is less than calm. Fortunately, naval architects have worked out ways to solve this problem, some of which can also be applied to conventional ship, and have even come up with a catamaran derivative, known as SWATH, that provides unmatched seakeeping for its size. But we'll start with an illustration of the basic principle at its simplest with the wave-piercing bow.

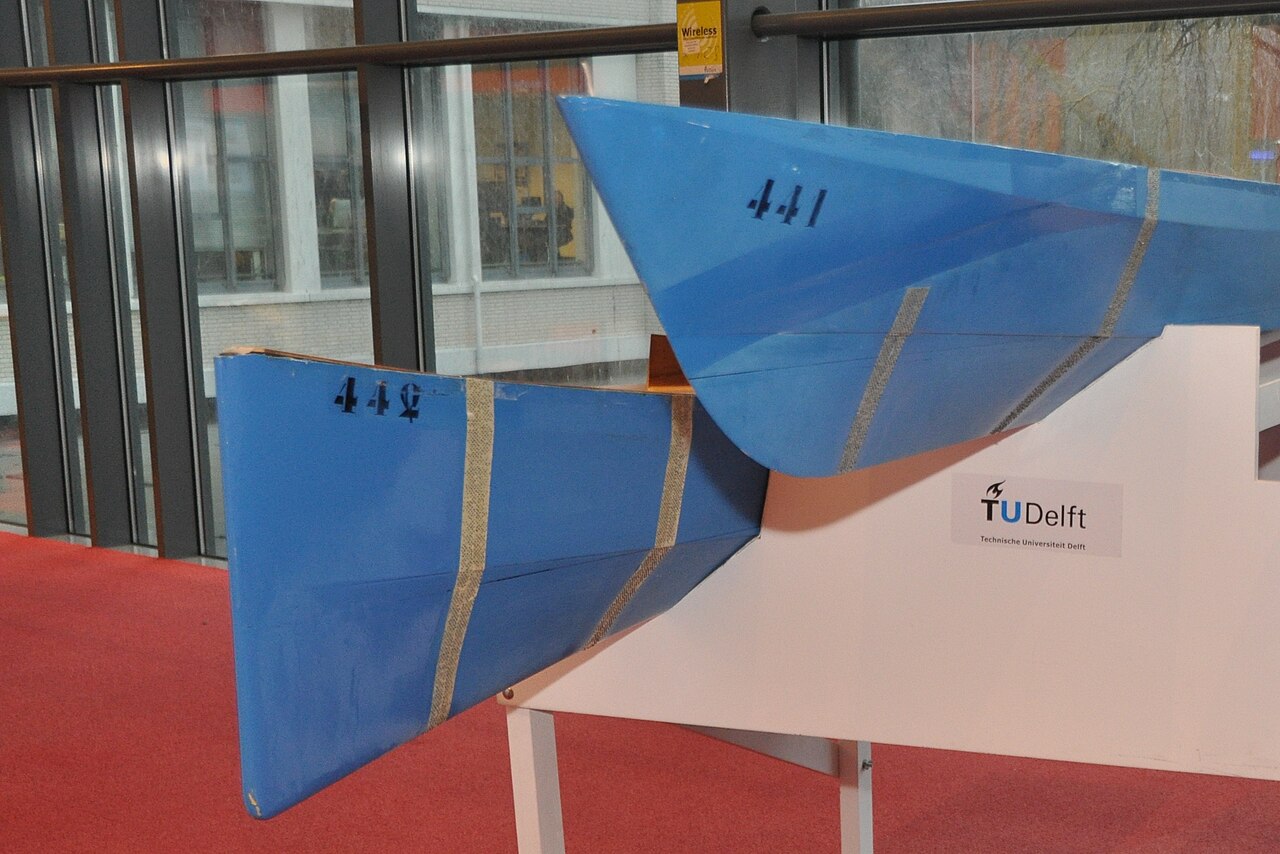

Axe-type wave-piercing bow and conventional bow, showing the different shapes

The basic concept behind a wave-piercing bow is simple. Imagine a normal ship is sailing along over a flat ocean, then runs into a wave. The bow is going to reach the wave first, and as the ship is horizontal, it will be pushed into the wave. This means that the waterline there will be higher than normal, and on a conventional bow there is quite a bit of flare,1 so the bow displaces more water, which means more buoyancy, which in turn pushes the bow up. The end result is that the ship will pitch up and down as it passes through the waves, which is the major cause of seasickness and also impairs decision-making. A wave-piercing bow has less buoyancy than a conventional bow, particularly above the normal waterline, and as such, pitches the ship less when it runs into a wave. The downside to this is that the bow rising keeps the water further away from the deck, so ships with wave-piercing bows tend to be pretty wet forward. This is a serious problem if the designer hasn't taken it into account,2 but can work if nobody is expected to be standing in the areas that keep getting wet.

Wave-piercing bows on HSV-2 Swift

Wave-piercing bows were adopted on high-speed catamarans because they encounter more waves more frequently, and because the catamaran configuration allows the deck to be a ways above the bows so it doesn't get wet, but the concept has recently been adapted for other uses. One case is offshore support ships, which routinely operate in extremely rough seas,3 and which have found that the reduction in pitching makes things better for their crews.4 Another is for stealth warships, most prominently the Zumwalts, which use a wave-piercing bow to try to minimize the ship's motion in the hopes of reducing its radar signature.

SWATH USNS Effective in drydock

But this principle can be taken further in the form of the SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull) configuration. Instead of merely trying to minimize how much buoyancy changes with the waterline at the bow, the SWATH does so for the entire waterline, by concentrating almost all of its buoyancy in a pair of pods deep under the water that are connected to the above-water portions of the ship by thin stalks. This way, if, say, a wave hits the ship crossways, as it climbs up one stalk, it produces only a very small amount of extra buoyancy, minimizing how much rolling force is produced.5 As a result, SWATH is the absolute best option if you are building a ship that is going to need to operate in very rough seas, and it has become popular for research vessels and the US Navy's SURTRSS vessels, ships designed to tow extremely large towed array sonars in the North Atlantic.

Sea Slice, a SWATH derivative with four underwater hulls

Of course, the SWATH is not without its drawbacks. Most prominently, as a ship gets heavier, it must displace more water, so it sinks down by an amount determined by the change in weight and the size of the waterplane area, which the SWATH configuration is designed to minimize. As a result, SWATH ships have to operate within a pretty narrow displacement band, to the point that the underwater hulls will need ballast tanks to compensate as fuel is burned off, as well as active control systems and the like. This makes them extremely unsuited to carrying cargo. There are other issues ranging from structural concerns to the issues of figuring out where the engines go so that they can have good access to air and to the propellers.6 In some ways, it's easiest to think of the SWATH as an above-water hull balanced on top of two submarines, and as such, it will always remain a niche type, invaluable in cases where a ship needs to operate in the worst possible seas.

German SWATH pilot boat Duhnen

In the late Cold War, the British, who for some reason were very concerned about protecting the North Atlantic shipping lanes, seriously investigated SWATH frigates for operations in that notoriously difficult stretch of water. They found that while a SWATH design was bigger and more expensive than a conventional ship of the same payload (6950 tons vs 5330 tons) it was far smaller and cheaper than a conventional monohull designed to provide the same seakeeping capabilities (9030 tons).7 The effect is even more pronounced for smaller ships, with Coast Guard trials of a 200 ton SWATH showing seakeeping equivalent to a 2500 ton monohull. Sadly, the SWATH frigate program ended up being a victim of the end of the Cold War, and as the probable center of naval conflict has swung to the Pacific, it seems unlikely to return.

1 The technical term for the bow sloping outward above the waterline, increasing the displacement added as the waterline climbs. ⇑

2 The Iowas have very fine bows with little buoyancy, and were quite wet forward, something I will now ascribe to premature adoption of the wave-piercing bow. ⇑

3 It's worth noting that the ability to tolerate rough seas scales with size, so a supertanker's crew might barely notice weather that makes things very uncomfortable for a platform supply ship with 1% of the displacement. ⇑

4 The most common form for this, the X-bow, is also touted as reducing drag due to the longer waterline it creates. I find this slightly silly, as you could just make a conventional hull longer, but at some point that might run into issues with dock sizes and the like. ⇑

5 "But bean," I hear the engineers reading this say, "doesn't that mean that it will have to roll a very long way to reach equilibrium again?" The answer to that is yes, it would, if it was going to reach equilibrium. But the sea moves, so there's no way for such a situation to persist very long, and the ship is big enough that the actual movement coming from the unbalanced force is pretty small. ⇑

6 This is much easier now than it was in the 80s, thanks to developments in electrical propulsion. ⇑

7 All numbers are from D.K. Brown's The Future British Surface Fleet. ⇑

Comments

How well do SWATH ships handle damage? If a missile, or a torpedo, or a suicide boat, or a drone, or something, hits the stalk, how much at risk is the ship? (I'm almost sure the naval architects have taken this into account, but for most navies it's been a few s/years/decades since they had to for-real worry about damage control...)

Seems like SWATH would do much better with nuclear propulsion.

Tony Zbaraschuk:

Probably about as well as a couple of submarines with a surface ship on top.

But I guess you can just add more hulls and the fact that they won't be as deep might help compartmentalization.

I'm not sure I've ever seen anything specific on that. I'd expect it to not be great, given that there's basically no reserve buoyancy in the conventional sense. You could compartment the underwater hull and hope to pump out ballast tanks and the like, but I suspect that's one of the more serious drawbacks for most warship use.

The new French FDI frigates have a wave piercing bow and the first of class Amiral Ronarc'h is undergoing trials, so there are some videos on YouTube. Haven't seen any footage of Amiral Ronarc'h in heavy seas yet, but there is a very distinctive horizontal "spray rail" around the top of the bow. ("Spray rail" is what the French commander called it, apparently no proper French term has been approved by the Académie Française yet.)

The French captain also pointed out that pitching and slamming is bad for all the electronics and computers on board, not just the humans.

@Hugh Fisher: underappreciated difficulty with modern ship survivability isn't that it will get sunk after a hit, it's that modern fiber-optics is unusually bad at handling shock and vibration.

So your ship might be able to handle a couple ASCMs and keep sailing...but none of the computers will work anymore.

This is also a factor people should consider when they start chimping out about "muh drone threat"-a lot of little drones won't be able to inflict the shock damage that one good armor piercing warhead would.

@Blackshoe,

Should we then assume that someone, somewhere, is running major engineering projects to develop shock-proof LANs, because once they get that proven then they can name their price?

I'm going to also assume that shock loading taking out the local network is also a problem with aircraft, armoured vehicles etc.

@Doctorpat;

Intensive work is done to improve shock resistance and otherwise fortify fiber optics systems, but my understanding is there's real limits to what can be done.

Going to stretch my knowledge here and say that my limited understanding is that the levels of shock damage that will knock out the electronics on an armored vehicle (ie large caliber shell hit or ATGM hit) or aircraft are probably kills anyway (or with the aircraft renders it such that it's only hope is to limp home). Ships being so large means there's a wider level of survivability.

@Tony Zbaraschuk "How well do SWATH ships handle damage?" @bean "I’d expect it to not be great, given that there’s basically no reserve buoyancy in the conventional sense. You could compartment the underwater hull and hope to pump out ballast tanks and the like,"

I disagree and believe that SWATH ships would be better at resisting damage than monohulls:

-Most modern Anti-Ship Missiles are nominally designed to hit the waterline, and drones like Ukraine’s Sea Baby or terrorist attacks like the USS Cole hit it by default. In a monohull this hits the largest compartments (engineering spaces) maximizing flooding and with a high likelihood of an operational kill via loss of propulsion. With SWATH the waterline is a narrow strut (perhaps a dozen feet thick on a Burke-sized SWATH) which would be empty or space used for tanks, which means a hit would blow a hole from the sea to the sea on the other side, not striking critical systems, and if hit tanks not even causing flooding. The attack on the USS Cole blew an approx. 40x40 foot hole; given that the distance from top of pontoon (with most of the buoyancy) and bottom of the “superstructure” (with critical system like power, sensors, weapons) would be some 24-37 feet on a Burke-sized SWATH it could potentially take a waterline hit from a weapon with 1000lb of explosives without significant damage (provided the transverse frames were sufficiently redundant that losing ~15% of them wouldn’t compromise the strut.)

-The most dangerous weapon for a monohull is a torpedo detonating under the keel, which for most vessels guarantees sinking. But a SWATH vessel has two “keels” and the centerline of the ship is above water. Again for a hypothetical Burke-sized SWATH, the pontoons would be 21-30 feet diameter. A torpedo designed to explode ~30 feet after influence (to be directly beneath the keel of a 66 foot beam DDG-51) would be just past to about 10 feet past the pontoon. Instead of contained under the hull the blast would have a path to vent to the atmosphere between the pontoons, which @bean has stated dramatically reduces the force transmitted through the water. There would of course be damage to the pontoon and strut, but again anything in the strut should be expendable, and whatever damage happends should be less than a contained explosion.

-If a weapon hits the “superstructure” above the water, a SWATH ship should also be less vulnerable. Monohulls must be long and narrow for hydrodynamics. But a SWATH is short and wide in comparison. For a monohull the key propulsion spaces in the hull run beam to beam, with non-critical berthing, mess and storage spaces fore and aft or above them. With SWATH, the non-critical spaces can be wrapped around critical spaces, providing a buffer to absorb blast. For instance, our Burke-sized SWATH could have a superstructure “beam” of 100-130 feet; if you kept a 66 foot wide engineering zone to match the beam of the actual Burke, then you end up with 22-32 foot wide buffer. This is as wide as the Torpedo Protection System of the best battleships, which where designed to absorb half a ton of explosives, much more than the average ASM. This raises the possibility of designing a compact “citadel” holding the critical systems (power, VLS, CIC) in the center of the superstructure surrounded by expendable space. This citadel could be armored the square-cube law means less armor needed than tradional 20th century armoring plans) or at least hardened (with Kevlar, spall liners, etc.).

-Another possibility with SWATH design (particularly the space below the “superstructure”) is to place VLS modules in channels with blowout panels, like on an M-1 Abrams tank, above the below the VLS. That way in a catastrophic magazine detonation the blast has a path up and down to atmosphere instead of out into the ship (again, assuming a sufficiently strong/armored tunnel). This could save a vessel from total destruction.

-Regarding the underwater pontoons, with modern electric propulsion placing the engines and generators in the “superstructure” above water, there is nothing preventing maximum compartmentalization of the pontoons, or even filling any voids with a modern version of the water excluding ‘ebonite mousse’ foam used on the Richelieu class battleships. This would help minimize the impact of flooding.

-Another area of greater SWATH survivability is propellers and rudders. This is a huge vulnerability for most ships, as the Bismark famously discovered. But a Buke-sized SWATH could have its propellers 100-150 feet apart, so a weapon hitting one would not affect the other. Steering is even less vulnerable. Monohull rudders are more fragile than propellers (hello again Bismark) but modern SWATH ships steer using inclined stabilizers/canards on the pontoons ahead of the propellers. They are removed from impacts on the propellers instead of next to them, and even better there are usually two sets, with one at the forward end of the pontoon hundreds of feet from the stern. Even if a hit disabled one propeller and both rear stabilizer, the ship would be fully functional with one propeller and the forward stabilizers to steer (if of course slower). I should note that integrated electric propulsion raises the possibility if adding propellers to the front of the pontoons for even greater redundancy (although I cannot speak to the hydrodynamic/turbulence impacts of this) or thrusters/propulsors at the front end that in addition to docking could provide limp home propulsion if both rear propellers were lost.

-SWATH ships don’t have reserve buoyancy in the conventional sense, but that doesn’t have to mean they have to have less reserve buoyancy. We think of reserve buoyancy being in the hull, with the superstructure as add on. But in a SWATH ship the “superstructure” (part of the boat above the water on struts) makes up most of the hull volume. Above water volume being more than below water volume is true of most ships; a Burke class hull is about 43 feet from keel to deck, but draft to keel is only 21 feet, and that is before accounting for volume of the superstructure. In monohull construction superstructure volume is not terribly usable for buoyancy because of stability issues once water is over the main deck. But SWATH ships are like a barge on stilts. Once the “superstructure” hits the water there is a lot of volume for buoyancy. It would be necessary to design for this, but no reason it couldn’t be done. A SWATH vessel in this instance would have terrible seakeeping and no speed to speak of, but from the point of survivability, after the Battle of Tassarfaronga the US Navy sailed the USS New Orleans from Guadalcanal to Australia and the USS Minneapolis from Guadalcanal to San Francisco Bay using jury rigged bows made of coconut logs! A SWATH ship floating on its superstructure is still floating and thus able to be repaired later.

The major issue with SWATH ships regarding damage has to remain as the question of asymmetric damage to struts/pontoons. This has been an open question regarding miliary catamarans as well. On the one hand the US building battleship engine rooms without longitudinal bulkheads suggests that asymmetric flooding and listing is a major concern. The US was willing to accept twice as much water coming in from a torpedo strike if the water was spread across the entire beam and did not cause list. On the other hand, catamarans are famously stable ships and resistant to capsizing (resistant, not immune, please do not run out and link to the “hey look a catamaran capsized” articles that populate sailing websites and blogs now and then). As noted above, a SWATH vessel with most of its volume in a superstructure above the water should be able to settle and float on that superstructure even if one pontoon were entirely flooded (or both flooded, to maintain a level posture). Stability and list are significant issues for a monohull with a narrow beam relative to length, a high superstructure and even higher mast. But a SWATH ship is MUCH wider, easily has a beam wider than height, and in a world of phased arrays and drones, a tall mast to mount radars is an anachronism. I’m not sure the asymmetric damage and list concerns are that significant.

My hypothetical Burke-sized SWATH above comes from some upscaling of the Sea Shadow and Sea Fighter, hence the range of values. Neither was a proper warship, and an actual SWATH destroyer would probably have a design with similarities and difference to both, so take these figures as indicative (as in “a SWATH vessel would have its propulsion units far apart”) not definitive.

Rather than being a niche, I think SWATH is the hull form of the future.

First is the reasons above I think survivability is higher. In the eternal cycle of arms and armor, if SWATH became common we would see weapons change as a result (missiles programed to hit high rather than at the waterline, torpedoes would go from underhull detonation back to side impact, etc.). However, there remains inherent survivability to a vessel design that minimizes volume and critical equipment at the waterline, and that makes the shape of the ship as compact as possible, allowing non-critical volume to wrap around more important spaces.

Second is of course stealth. There is a reason that SWATH was used as the hull form for the Sea Shadow stealth demonstrator. SWATH was also used for the US Navy’s SURTASS sonar surveillance ships. In addition to the obvious radar stealth from sharply sloped sides SWATH can dramatically reduce wake; wake is an underappreciated signature factor, a vessel creates a wake much larger than the ship, to the point that it can be visible from space and picked up on radar. SWATH can also lower thermal signature by venting hot exhaust down into the space between the water and the superstructure.

A third reason is the width and associated flight deck. @Bean has noted this as advantage of the Independence class LCS with its trimaran design. As of yet, aircraft remain the most potent naval weapon; surface ships with missiles can be thought of “small kamikaze aircraft carriers”, everyone agrees that ASW helicopters are the main threat to submarines not the ship that carries them, and UAVs are dramatically changing everything. The wide beam of a SWATH ship could provide a flight deck 110-130 feet wide, which means it could be large enough to support MV-22 and CH-53 operations, or a anti-submarine derivative of the future MV-75 tiltrotor that will replace Army Blackhawks. That kind of “deck estate” also could facilitate simultaneous UAV launch and recovery.

Note that some of these advantages trade off with others. For instance, maximum stealth would want all intakes, exhausts and hatches “underneath” the superstructure between the struts where they are hidden from view by radar and other sensors. This, however, compromises with survivability; if the SWATH were to settle on the superstructure due to flooding in the submerged pontoons, then you lose all main propulsion. Openings below would also compromise the watertight integrity you want for reserve buoyancy in the superstructure. Yet compromises like this are what ship design is all about. The Iowa class was much larger than the South Dakota class yet had virtually the same level of protection – all of the additional weight went into speed.

With that in mind, for warships, SWATH appears to provide the greatest flexibility in making these compromises when looking at stealth (obviously), survivability (no systems at waterline, a compact “citadel” surrounded by standoff space), and flexibility (wide beam and stable platform).

Interesting analysis of potential survivability of a SWATH, but I'm not sure it actually works. The problem with "struts are small, so damage from a waterline missile hit is minor" is that the ship still has to balance afterwards, and the mechanism that lets SWATH pass through the sea level with minimal disruption relies on the disruption not lasting very long. Imaging what happens in a flat calm. The loss of all that buoyancy on one side means that side sinks until the buoyancy is made up, and you get crazy lists from even relatively minor damage. You'd probably have to flood down the other side quite a bit or something.

This is also my criticism of floating on the central hull. It would work, no question there, but it's going to be triggered pretty easily and once it happens then the ship is going to be vastly slower. And it wouldn't take all that much damage to trigger it. The advantage of more conventional hulls is that they're going to degrade fairly slowly.

"The problem with “struts are small, so damage from a waterline missile hit is minor” is that the ship still has to balance afterwards, . . . The loss of all that buoyancy on one side . . . ."

I guess the issue is that I do not see a hit on the struts as causing the loss of a lot of buoyancy. Remember if there is not a lot of reserve buoyancy in the struts to take on extra load (the reason SWATH would be a terrible cargo ship), then there also is not a lot to lose. Again taking the Cole case of a 40 ft x 40 ft hole at the water line, a strut a dozen feet thick would only admit ~300 tons of water (a volume 40 ft x 20 ft x 12 ft, with half of the hole being above the waterline). That's 3% of a 9600 ton ship; and a loss of a 2-3 ft of "freeboard" when you have 15-20 feet. Any list is a problem that can be solved by pumping 150 tons of fuel from the damaged pontoon/strut to the other, just 10-15% of total ships load. This isn't insignificant, but it also doesn't seem critical.

But remember that if you put your fuel (and other fluid) tanks in the strut at the water line, and they are relatively full, then you take on almost no load at all, just as in the torpedo defense systems of battleships. If that 40x20x12 space was already full of fuel, then you are only adding ~60 tons of weight, since ~240 tons of fuel was already there.

"you get crazy lists from even relatively minor damage."

Except that I don't think you get crazy lists out of a SWATH, or other multi-hulls for that matter. A list of just 28 degrees would mean that a Sea Shadow design would have one strut/pontoon fully submerged and the other out of the water, but that is effectively impossible because it would mean that the center of gravity was somewhere outside of the superstructure, which I don't think could happen even if the submerged strut/pontoon were fully flooded as the end of the other strut/pontoon would be suspended horizontally more than 100 feet and exerting incredible leverage to right the ship. Instead of a crazy list, in the event of major flooding I see some list then the ship floating on the central hull.

Here you have a good point that floating on the central hull would be triggered more easily, as the amount of reserve buoyancy in the struts is low, even if total buoyancy of the vessel is not. I took the view that this was advantageous in the event of catastrophic damage below as the central hull would be less affected. Again, I think of the USS New Orleans sailing backwards to Australia from Guadalcanal after losing its bow - a ship that is combat ineffective but still afloat can be salvaged. But perhaps you are correct that you would end up with too many operational kills from lesser damage, and you lose the battle from not having enough ships in the fight, even if they are not sunk. I could see ways to mitigate this (shaping the bottom of the central hull to provide some level of seaworthiness if it settles in the water instead of becoming a hydrodynamic brick, as I mentioned before thinking about where you place intakes and exhaust) but I could also see it being the key flaw.

OK. I think the issue here is that you're looking at the problem as purely one of loss of buoyancy/addition of weight, when there's also a second problem: loss of waterplane area, and consequent loss of stability. Let's say we have a SWATH with two struts, each 35' long and 2', which conveniently gives us 2 tons per inch of immersion. (A long ton is 35 cubic feet of seawater.) Say a missile hits one and blows the middle 50% out. Now, that side has only 1 ton per inch of immersion. You can fix this in a static analysis by ballasting the ship, but once you start thinking about dynamic effects, things get bad fast. For any addition or subtraction of weight, the damaged side will move twice as much as the undamaged side, to say nothing of what happens when the ship turns or rolls. And, yeah, list is limited by "we've started exposing pods/immersing hulls", but those are both likely to be bad things. (To be clear, loss of waterplane area can be a serious problem for conventional ships suffering from flooding, but by nature they have a lot of waterplane area to play with. A SWATH doesn't.)

In a given battle, a mission kill is as good as a hard kill. After the battle, not so much, but even then, you have to actually get the ship back to be able to repair it, and that's not guaranteed. During WWII, quite a few ships that were theoretically salvageable had to be scuttled because they couldn't leave a dangerous area fast enough, and it wasn't worth risking more forces to protect them. Hornet is probably the prototypical example. The most famous counterexample is Houston and Canberra in October of 44, where IIRC there was serious discussion of scuttling both ships before the decision was made to get them back to Ulithi. New Orleans (and Minneapolis, who suffered similar damage in that battle) were lucky in that there was a nearby port they could reach where repairs could be made. Had they taken that damage further up the Solomons, they probably would have had to be scuttled, too.