In our recounting of exotic hullforms, it is now time to leave things that are clearly ships, no matter how weird, and venture into the realms where air starts to play a major part in the design, possibly to the point that the thing in question isn't really a ship any more, because the thing isn't limited to operations over the sea. Despite this, they still fall broadly in the realm of naval vessels, as various limitations mean that they rarely see service in purely terrestrial roles.

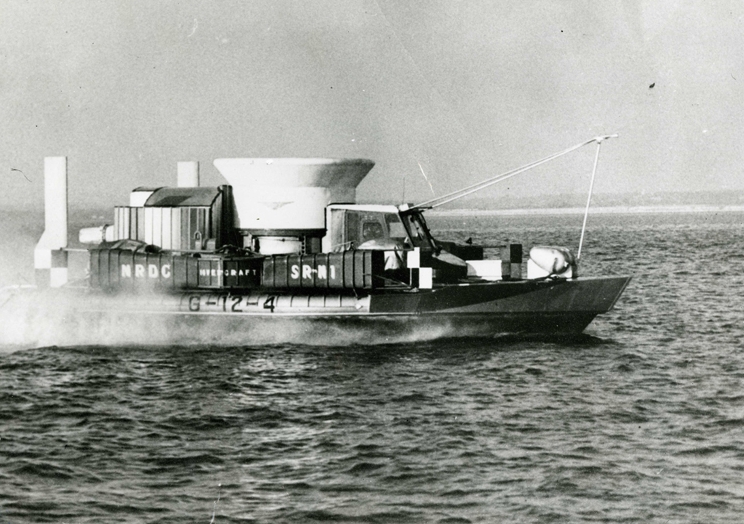

SR.N1, the first true hovercraft

The basic idea is to take advantage of air's much lower density to decrease drag by injecting it underneath the craft to provide lift. Both the simplest and most common version of this is the hovercraft, which at its essence1 involves using a big fan to pressurize the air under the vessel until the pressure counteracts the weight and lifts it off the ground. The result has effectively no friction and can float over almost any surface, but runs into a simple problem: the amount of air escaping is proportional to the height above the ground, so a low-powered hovercraft will have very little ground clearance, and very limited ability to handle rough terrain or waves, with the first prototype being flummoxed by anything bigger than about 9". While there were some potential uses for this technology, it wasn't really suitable for nautical use, at least until someone suggested adding rubber skirts, which would raise the body of the hovercraft much further and make it possible to cross obstacles. The results were dramatic, with the rebuilt prototype, fitted with 4' skirts, able to handle 3'6" obstacles and operate in 6-7' seas, all while having twice the lifting capacity on the same power. Propulsion was generally provided by aircraft-style propellers, and the lack of any direct contact with the surface meant that speeds of 75 kts or more were fairly easy to achieve, even in moderately rough seas.

This groundbreaking combination of characteristics drew immediate attention from several sources. Its high speed made it a compelling alternative to the hydrofoil in the high-speed ferry market, particularly as a big enough hovercraft could carry reasonable payloads, including cars,2 and it could operate with relatively little infrastructure, requiring only a ramp to enter and leave the water, and deflating the skirt when it was time to disembark. The British were the most enthusiastic about this technology, and for several decades operated massive SR.N4 hoverferries across the English Channel, each capable of carrying 60 cars and 400 passengers. The service finally died in 2000, thanks to the increasing age of the hovercraft, the opening of the Channel Tunnel, competition from catamarans and the end of duty-free shopping within the EU. Today, the only remaining British hovercraft ferry runs between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight,3 and information on other operators is difficult to find. A relatively small number of hovercraft are used by various governmental operators for rescues in conditions where conventional boats or ground vehicles simply wouldn't work, and some very small hovercraft are sold for recreational use.

Zubr class LCAC

But there was one obvious customer for a vehicle capable of traveling over both land and water: the world's amphibious forces. Since the end of WWII, there had been an increasing sense that WWII-style amphibious operations, with lots of ships parked close to the shore, were no longer feasible. Even disregarding the threat of nuclear weapons, the chances of someone with a pair of binoculars, a telephone, and the number of a battery of anti-ship missiles ruining your day were just too high. The obvious answer was to make the landing craft themselves considerably faster, but this proved difficult, particularly when combined with the need to run them aground on the beach.4 A partial solution had already been developed in the form of the helicopter, but while they were fast and able to drop troops well inland, they were also expensive to operate and couldn't move heavy vehicles. The hovercraft took care of several problems at a stroke. Not only was it fast, capable of carrying tanks and able to move some ways inland, it also allowed attackers access to a far greater array of beaches. Traditional landing craft require specific combinations of bottom type and beach slope, which limit them to less than 20% of the world's beaches. But a hovercraft can easily cross rocky beaches and doesn't really care about what the underwater bottom looks like, raising the proportion of suitable beaches to something more like 70%. This complicates the defender's problem immensely, which is music to the ears of amphibious planners.

An LCAC carrying equipment

The Soviets were the first to introduce a hovercraft in this role with the Gus class in 1969, and their interest has continued with the Lebed, Aist and Zubr classes, the last being the world's largest hovercraft at 550 tons fully loaded. The USN took slightly longer to build the imaginatively-named Landing Craft, Air Cushion (LCAC), which entered service in 1986. Capable of carrying up to around 70 tons at 40 kts, or hitting 70 kts while empty, the Marines have considered it the greatest advance in amphibious warfare since the helicopter, despite the teething problems that it brought. Existing well decks were designed to carry long, thin craft like the LCU, and in at least some cases, they had very little ability to carry LCACs. On the other hand, the LCAC could be deployed and recovered without having to flood down the well deck, which saved quite a bit of time and hassle. And because it is built to aircraft standards, it's quite vulnerable to damage, although it is generally hoped that its mobility means it can find an undefended beach to cross.5

A Royal Marine hovercraft in Norway

The only other major user of big amphibious hovercraft is China, with a few imported Zubrs, as well as several indigenous types of various sizes. South Korea has a small number of their own design, while Japan has bought a few LCACs from the US and Greece has imported a few Zubrs from Russia, presumably for operations among the islands of the Aegean. A number of nations operate a small number of passenger-only hovercraft for a combination of landing troops and patrol in regions where their ability to move over land and shallow, debris-chocked water gives them a decisive advantage over normal boats. This role dates back to the Vietnam-era PACV, which was not particularly successful due to its noise, limited range, and inability to climb the steep river banks common along South Vietnam's rivers. More recently, most countries use Hoverwork 2000TDs, although the Russians have their own version.

A civilian SR.N4

There is one feature of the hovercraft that makes it particularly suited for the patrol role, and that has inspired interest in other roles as well: it is nearly immune to mines. Against land mines, a hovercraft's extremely low ground pressure6 means that even anti-personnel mines are unlikely to be set off, while the signature of a hovercraft over water is totally unlike that of a normal ship, making it unlikely to set off influence mines. Even if one does go off, the air cushion provides an extremely effective buffer, with the SR.N3 hovercraft surviving seven 1,100 lb charges during trials, the last close enough to drench the hovercraft but leaving her entirely operational. Other trials showed that they were quite capable of operating a towed surveillance sonar, and their ability to work from any suitable beach was a major advantage, too. The British determined that the SR.N4 cross-channel ferry inherently met the acoustic signature requirements,7 and could easily be modified to meet the magnetic signature requirements. The system as a whole would be cheaper to buy than a conventional vessel, but significantly more expensive to operate, making cost analysis difficult, and the project was never ordered into production.

An LCAC enters the well deck of Ponce

Cost is by far the biggest drawback to hovercraft in general, thanks to the fact that they are in many ways more conceptually similar to aircraft than to ships, with all of the costs that implies. They are also extremely noisy, which not only makes them unpopular neighbors, but often has tactical costs as well. And the range is generally quite limited, as they must either be hovering or they won't go anywhere.8 And while these are balanced out in a few applications by its unique ability to move from land to water and back again, there were some engineers who wondered if there might be a way to combine its high speed with better seagoing performance if operations on land were not an issue. We'll take a look at the results of their efforts next time.

1 Actual hovercraft are somewhat more complicated, using a ring around the edge of the craft to inject the air, which forms a sort of "wall" and greatly reduces power consumption, an innovation made by British engineer Christopher Cockerell. ⇑

2 It turns out that big hovercraft are more efficient than small ones. Power required to hover is mostly driven by how much air is leaking out of the skirt, which increases proportionally with the length of the skirt, while load carriage is proportional to the area within the skirt. Doubling the size of a hovercraft doubles required power but raises lift area by a factor of four. ⇑

3 I believe this continues to be economical because of the relatively large tidal range in the area, which leaves one end of the route a mile from the sea at low tide. ⇑

4 The USN looked very seriously at hydrofoil landing craft, going so far as to build prototypes. This was better than most options, as the hydrofoils could retract before beaching, but still not great. ⇑

5 Because the original LCACs are getting rather long in the tooth, the US is currently building replacements under the Ship-to-Shore Connector (SSC) program, which is basically "LCAC, but slightly more capacity and easier to maintain". ⇑

6 A typical human standing exerts something like 2.5 psi, while a fully-loaded LCAC is more like .7 psi. ⇑

7 This was true even when turning, which is about 10% of the time, and wasn't true for the contemporary Hunt class. ⇑

8 It is worth noting that basically all hovercraft will float if the skirt deflates while on the water, and can even be started from this position. But the demands of hovering and the demands of being a boat don't play well together, so this is undesirable and results in speeds of single-digit knots. ⇑

Comments

My dad did several trips in the SR.N4; sadly I never got to accompany him. He described it with the noise and spray as "like crossing the Channel in a washing machine"

Oh boy, are we about to get into my favorite recurring oddity of the COLREGs, WIGs?

Yes. Yes we are. (There. Now it's official, and people can stop asking me that.)

Hovercraft buffs should consider a visit to the hovercraft museum at Lee on Solent in the UK (not far from Portsmouth). It is volunteer run and a bit tatty, but they have a huge range of hovercraft.