In the late 40s, airplanes were the obvious means of projecting nuclear power from the sea. After all, airplanes were the core of existing long-range striking power, and the USN was working hard to integrate them aboard its carriers. But airplanes require big, expensive ships to operate from, and the Soviet Union in particular didn't have any available. Even if they did acquire some, which was doubtful with Stalin still running the country, their life expectancy in the face of the USN would be short at best.

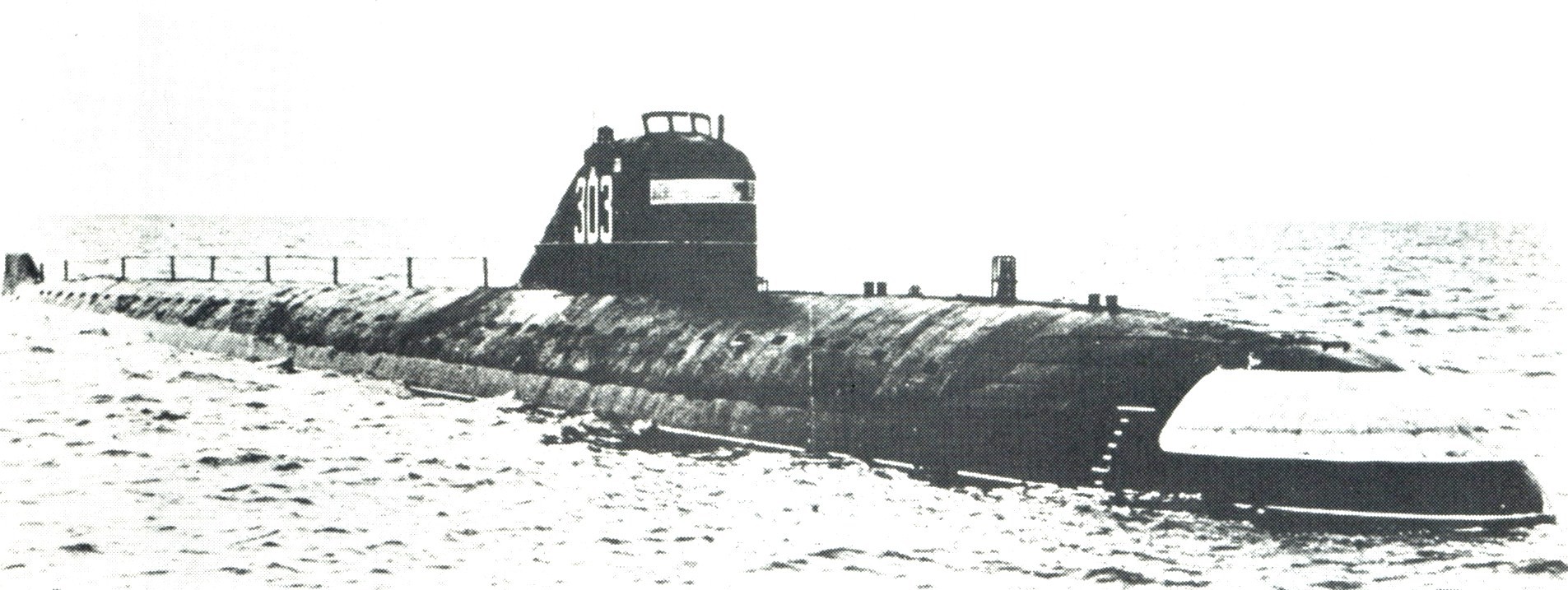

A November class submarine

Instead, they turned to the traditional weapon of weaker maritime powers, the submarine. Cruise missiles, inspired by the German V-1, were the obvious weapon of choice for such a task, but such weapons were still in their infancy. The Soviets came up with another plan: the nuclear-armed torpedo. But not just any torpedo. The T-15 would be 1.55m in diameter, 23.5m long and weigh about 40 tons. Each submarine would carry a single torpedo to a position off a major naval base or port, surface to confirm its position with radar and stellar sightings, then launch the 30-knot torpedo at its target about 16 nm away. The size of the weapon was driven by its thermonuclear warhead, as early examples of such weapons reached enormous size. The T-15 would be carried by the Soviet's first nuclear submarine, with the propulsion selected due to the need for rapid long-range transits. After Stalin's death in 1953, the Soviet Navy found out about the program and quickly decided that it didn't have much use for the T-15. The weapons fit was changed from a single T-15 and a pair of single-shot self-defense 21" torpedoes to 8 conventional torpedoes for use in more normal submarine missions. The resulting boats, designed the November class by NATO, were the USSR's first nuclear submarines.

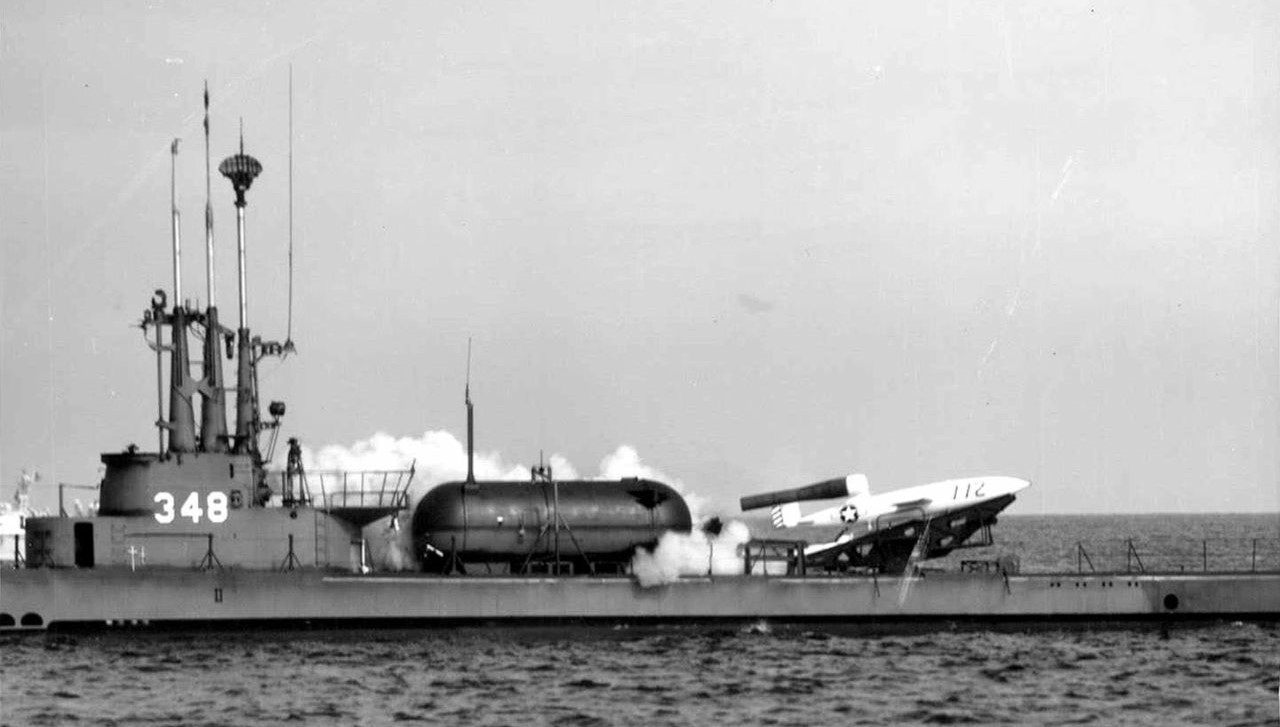

A Loon being launched from Cusk

But even as the T-15 died, nuclear cruise missile programs were alive and well on both sides of the Iron Curtain.1 American cruise missile programs had begun in 1944, with the capture of German V-1 components, which led to the creation of an American copy, the JB-2. Thousands of JB-2s were ordered to aid in the bombardment leading up to the planned invasion of Japan, then cancelled when Japan surrendered. The leftovers were useful in the development of cruise missile technology. The Navy decided it was time to investigate submarine-launched cruise missiles, and in early 1947, the ex-fleet submarine Cusk launched the first JB-2, which the Navy called the Loon. She and her sister Carbonero carried out numerous firings over the next few years, gaining valuable experience that would be applied to the operational cruise missile the USN was developing, known as Regulus.

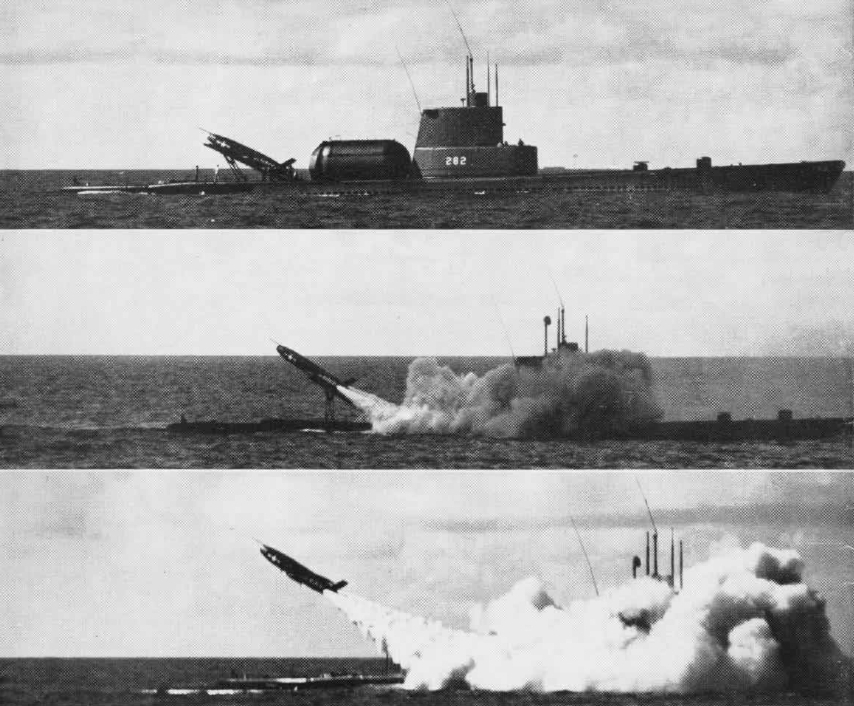

A Regulus on its launcher

Regulus began development in late 1945, when Vought Aircraft was awarded a contract for a subsonic, jet-powered cruise missile intended for launch from submarines, as an alternative to the carriers in the strike role. The advent of nuclear weapons made this practical, and the nascent Regulus was a minor part of the USN's efforts to break the Air Force's nuclear monopoly. Regulus, at 32' long and almost 14,000 lbs, was the size of a typical WWII fighter, and was much more like a pilotless airplane with a Mk 5 nuclear warhead than a modern cruise missile. The first test flight took place in November 1950, but lasted only a few minutes before problems with the radio-control system led to a crash. Most Regulus development was done using so-called Flight Test Vehicles, which had retractable landing gear and could be flown onto a runway from a chase plane, making the test program much cheaper than it would have been if each missile only flew once.2

A Regulus launch from Tunny

The operation of Regulus wasn't particularly complex. The carrier submarine would surface up to 575 miles from the target, and the crew would bring the Regulus out of the hangar and onto the launch rail, then extend its wings and elevate the rail. With that done, the whole process taking about 10 minutes from the time the submarine surfaced, a pair of JATO boosters would throw it into the air, where a jet engine would take over. The launching submarine tracked the missile with its radar and radioed guidance updates, a task usually taken over by a second submarine, not armed with the missile, stationed closer to shore to improve accuracy. While the launching submarine had to surface, the guidance submarine could remain at periscope depth, improving survivability. When the missile was close to the target, a final signal would send it into a dive, which could see it breaking the sound barrier before an altimeter set the warhead off.

USS Grayback

The first submarine converted to carry Regulus was USS Tunny, a former WWII fleet submarine with a hangar capable of carrying two missiles fitted aft of the superstructure. Tunny launched her first Regulus in July 1953, and was joined two years later by another conversion, Barbero. Barbero is most notable for her participation in "Missile Mail", where a post office was established aboard her, 3,000 postal covers were postmarked and loaded onto a Regulus, which was then launched and landed ashore by a chase plane. The two conversions were soon joined by a pair of purpose-built diesel Regulus boats, Growler and Greyback. Technically, Greyback was laid down as an attack submarine and converted while under construction, while Growler was built from the keel up for the job, but in practice, the two boats were very similar. Both had a pair of missile hangars integrated into the forward hull, each capable of carrying two Regulus. These were followed by a single nuclear-powered Regulus boat, Halibut. She was designed with the future Regulus II in mind, and had a single hangar capable of carrying five of the existing missiles or four of the newer ones. 11 more SSGNs were planned, but they were cancelled as the Polaris ballistic missile program gained steam.

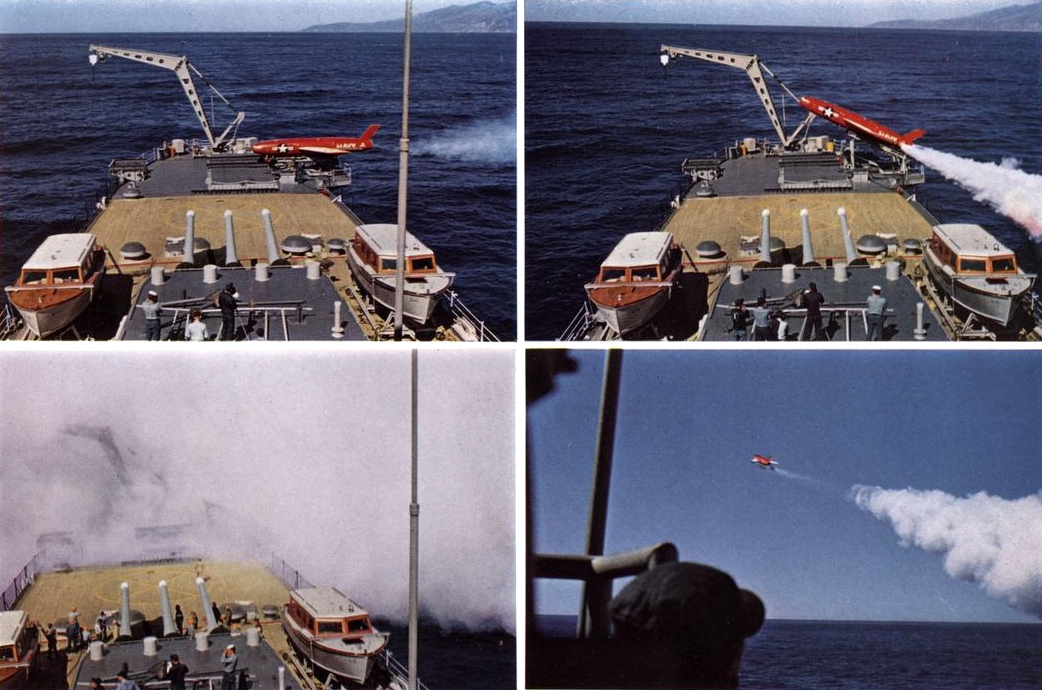

A Regulus launch from Hancock

While Regulus was designed for use from submarines, the Navy realized that it could look at other launch platforms, and both carriers and cruisers were investigated. The first tests were conducted in late 1952 from the test ship Norton Sound and the carrier Princeton, and both were successful. The new missile wasn't particularly popular with naval aviation, who saw it as infringing on the manned nuclear delivery roles, but the cruiser force welcomed it as a way of getting long-range striking power onto their ships. Acceptance aboard carriers was also complicated by the mess it made of deck operations. The rocket launch system tended to block up the deck, and the carrier had to bring with it a detachment of aircraft to guide the missile in flight.3 After the carrier Hancock almost lost a launcher, missile and all, over the side during a sharp turn, Vought developed a cart that allowed Regulus to be launched by a carrier's catapult instead, which at least made the situation slightly better. Despite this, Regulus made only a handful of carrier deployments in 1955-56 before being removed in favor of the A4D Skyhawk.

The launching sequence for a Regulus aboard Los Angeles

The cruiser Los Angeles was actually the first platform to deploy with Regulus, taking the missile to the Western Pacific in 1955. She and three other Baltimore class heavy cruisers received a launcher on the stern and three missiles in the hangar that had previously housed their floatplanes. Los Angeles made a total of six deployments to the Western Pacific with Regulus onboard before it was removed in 1961. Helena and Toledo also made WestPac Regulus deployments, while Macon deployed it with the Atlantic fleet, taking missiles to the Mediterranean in response to the 1956 Suez Crisis.

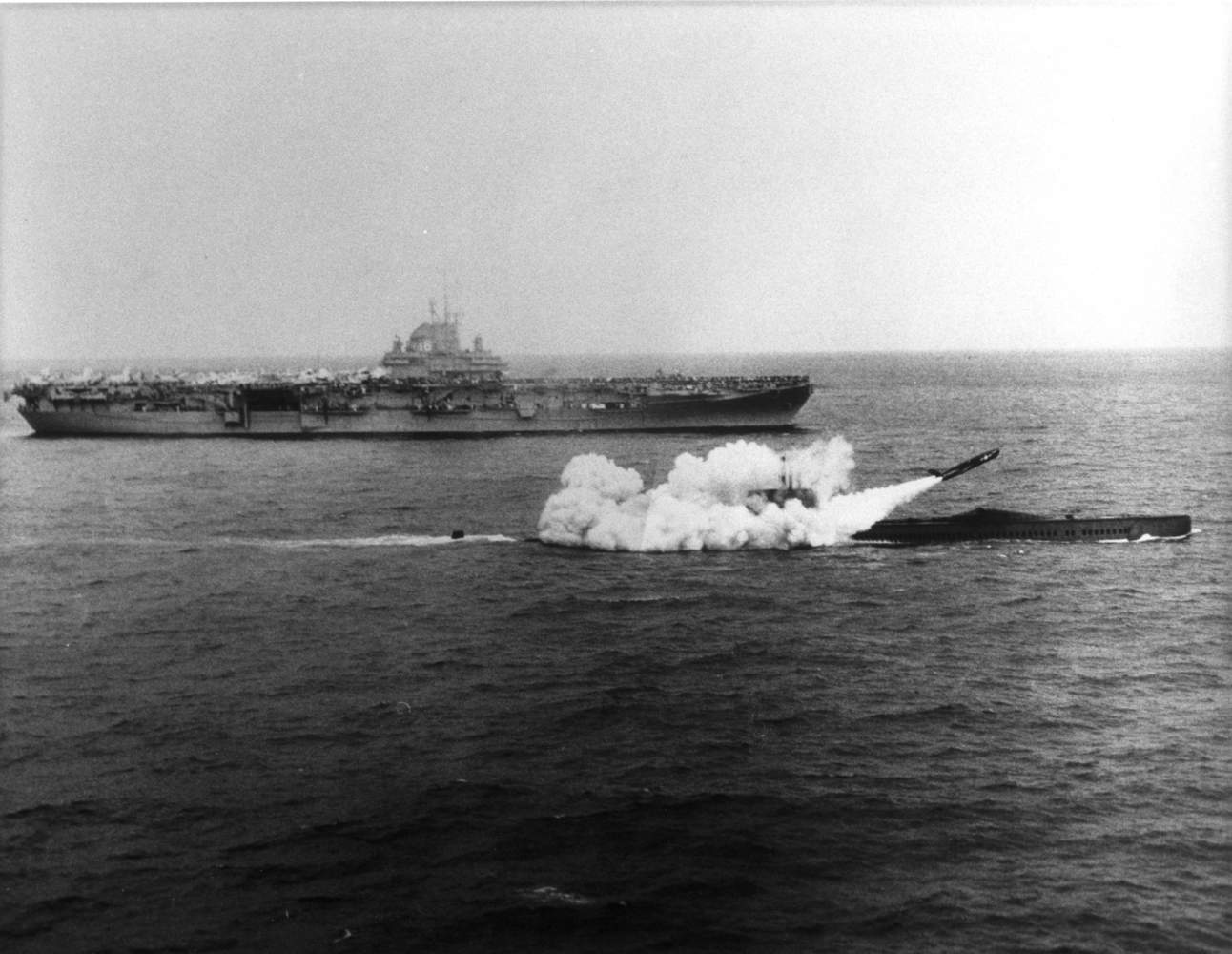

Halibut firing a Regulus, with Lexington in the background

But the ultimate users of Regulus were to be the 5 submarines, which deployed sporadically in both oceans, including in response to the 1958 Lebanon Crisis. The next year, operations were consolidated in the Pacific, and continuous deterrent patrols began. From October 1959 until June 1964, at least one missile submarine was always on station off the Soviet Pacific coast, carrying missiles that had by this point been upgraded with the W27 thermonuclear warhead. For some reason, the separate guidance submarines weren't deployed, which meant that the submarine's launch points had to be just off the coast. The patrol schedule was grueling for the crews, as unlike the Polaris submarines starting to come online in 1960, they had no relief crews.4 Things were even worse from 1961, when Barbero and Tunny, already the oldest and least pleasant of the Regulus subs, began to deploy together to ensure that at least four missiles were on station at all times. All of the boats except Halibut had to come to periscope depth every night to snorkel and recharge their batteries, which could be extremely unpleasant if there was a typhoon in the area, and many patrols resulted in damage from this practice. Ice also posed a threat, badly damaging Growler on one patrol.5

Halibut as a special missions submarine, with a diver airlock on her stern

Halibut carried out the 40th and last Regulus patrol, which ended in July 1964. The first Polaris submarines had reached the Pacific, bringing with them 16 missiles and far greater endurance. Barbero was sunk as a target later that year, while Tunny was converted to a transport and used in support of special operations. Grayback and Growler were placed in reserve, and Grayback was eventually converted to a transport to replace Tunny, operating off Vietnam. Growler was never modified, and eventually was donated to the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City, where she can be seen today. Halibut had by far the most interesting career of the Regulus submarines. Her massive hangar made her ideal for the Navy's deep-submergence program, a group tasked with gaining the advantage in the undersea war with the Soviets. Halibut was modified to tow a "fish", a 2-ton tethered vehicle that could scan the ocean bottom with sonar and cameras, looking for things the Soviets had left down there. The most famous of those things was a Golf class missile submarine that sunk under mysterious circumstances in 1968. The CIA decided that the best thing to do was build a ship with a giant claw that would scoop the submarine off the bottom. This effort, known as Project Azorian, didn't go particularly smoothly, as the submarine broke up while being raised. Halibut also spent a great deal of time much closer to the Soviet Union, most prominently tapping a cable that ran to the Soviet missile submarine base at Petropavlovsk. This operation, known as Ivy Bells ran for almost a decade before it was compromised, and other cable tapping missions were carried out by a variety of submarines. Halibut herself was retired in 1976, with most of her missions taken over by the modified attack submarine Parche, the most decorated vessel in the history of the US Navy.6

A Regulus aboard Growler today

But Regulus was far from the only nuclear cruise missile developed in the 1950s. Before ballistic missiles killed them off, both the US and Soviets were busy developing cruise missiles for use by their submarines, and we'll take a look at these next time.

1 Note that I am limiting my scope to sea-based cruise missiles, with a limited look at land-based weapons. Air-launched cruise missiles have been covered elsewhere. ⇑

2 Regulus was very similar to the Air Force's Matador cruise missile, using the same engine and having very similar performance. At one point, the Navy was directed to investigate if Matador could be adapted to the Navy's needs. Unsurprisingly, it was not suitable for operations at sea, thanks to guidance system limitations and a rocket booster that wouldn't fit well aboard submarines. Nobody seems to have suggested buying Regulus for both services. ⇑

3 Handing the missiles off to guidance submarines was successfully tested, and would have allowed the missile's full range to be used. ⇑

4 Polaris submarines had "blue" and "gold" crews who would trade out after each patrol to ensure they got downtime. Regulus crews joked that they were on the "black and blue" crew due to their deployment schedule. ⇑

5 One advantage was that the patrol area was in a region inhabited by king crabs, which were captured using homemade traps left one night and hauled up the next. ⇑

6 If you want to know more about the American underseas intelligence campaign, I highly recommend the book Blind Man's Bluff, which should be easy to find in your local library. ⇑

Comments

Using a photograph of a submarine that never carried cruise missiles for the lead is a bit amusing.

It's not about the cruise missiles, it's about the T-15. Which I couldn't ignore, and it fit best here.

It always amazes me that VLS cells took as long to come up with as an idea as they did. I realize that building them wasn't trivial, it's not just a hole in the deck. And to be really useful you needed the size of missile to come down a bit from regulus sized beasts, but still. When you look at pre-VLS missile launch systems and how much time and work they took, you wonder how it took 30 years of missile armed ships to come up with "let's put them in a box facing upwards"...

It didn't take that long. For SAMs, it did take a while, but Shaddock was launched from pods, and it was only a few years behind Regulus. I think a big part of the issue was that Regulus was built like an airplane, not like how they learned to build missiles.

Macon deployed it with the Atlantic fleet, taking missiles to the Mediterranean in response to the 1956 Suez Crisis.

So the USA was threatening to nuke Paris or London?

That would have made history take a different path.

Not quite, although that was probably what it felt like in London or Paris. The issue was just that it spiked international tensions, and as such the US wanted more forces in the Med in case the Soviets started something.

Aye, though even Shaddock's successor, Sandbox/Bazalt, was still mounted in above-deck canisters. They didn't take to sinking those into the hull until Shipwreck/Granit. Did anyone have a proper VLS prior to about 1980? (Kirov is the first one I know of, other than the trial S-300 installation on Azov; AFAIK)

There's a bunch of different factors which play into the ideal launching mechanism. One thing that springs to mind is that above-deck canisters are less likely to land a faulty missile on the launching ship. They're also easier to fit if you're using really big missiles, which the Soviets usually were. As for proper VLS, the first one I know of was 1958, but it didn't break out of that niche until, as you say, around 1980.

I second the recommendation for Blind Man's Bluff. I own a copy myself.