Battleships were the pinnacle of warship engineering during WWII, and as a result, they took a very long time to build. So long, in fact, that almost all of the major powers had battleship classes that were stillborn on the slipway during the war. Battleships that were not already far along at the outbreak of the fighting were usually suspended to free men and material for other priorities - submarines, aircraft carriers, escorts, transports and landing craft. And then, when peace came, they were cancelled altogether, viewed as relics in the age of missiles and jets.

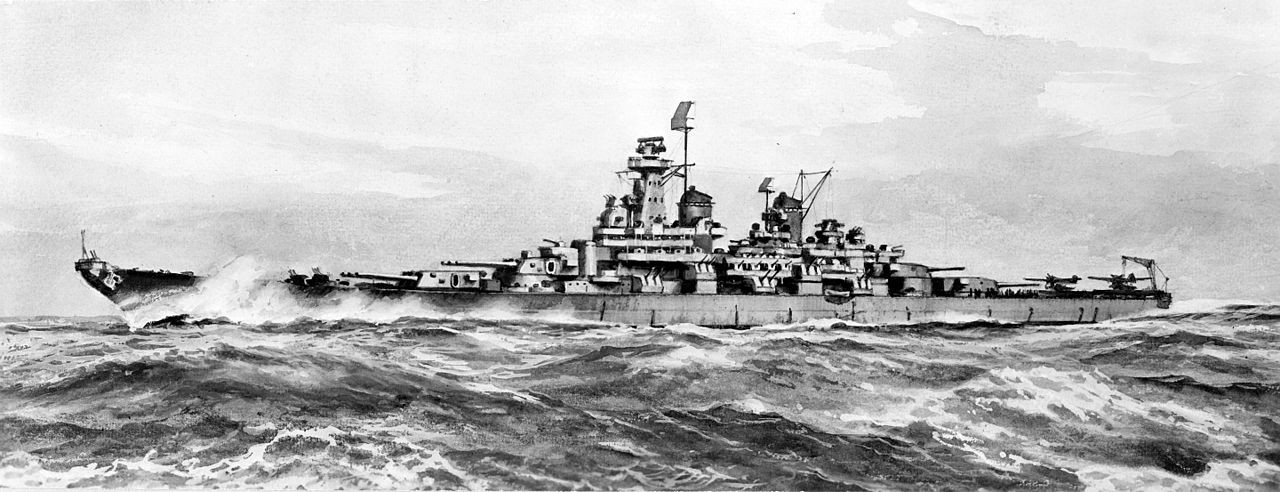

An artist's impression of Montana

But there are fascinating vessels among these last, unfinished chapters of the story of the battleship. Unhampered by the naval treaties, these vessels could grow to the constraints set by the physical infrastructure of drydocks, harbors and canals, or even a bit beyond. But we'll begin with one of the relatively moderate examples of the breed, the American Montana class, the last battleships ordered by the United States.

The Montana class began as the more traditional alternative to the Iowa class, focusing on firepower and protection instead of the latter class's rather atypical speed. In 1938, several sketches had been made of 27-kt ships with either 12 16" guns or 9 18" guns, although the extra turret required enough length that only the 18" ship could afford any increase in protection over the South Dakota class. This wasn't particularly compelling, and the USN decided that it needed a carrier escort more than it needed a battleship with 33% more firepower, so it built the Iowas instead. But the USN would always choose protection and firepower over speed in the end, and so the idea of the slow battleship was never too far from the minds of the designers. In mid-1939, with Iowa and New Jersey ordered under the FY40 budget and plans firming up for another pair in the FY41 budget, studies of a new 27-kt battleship began.

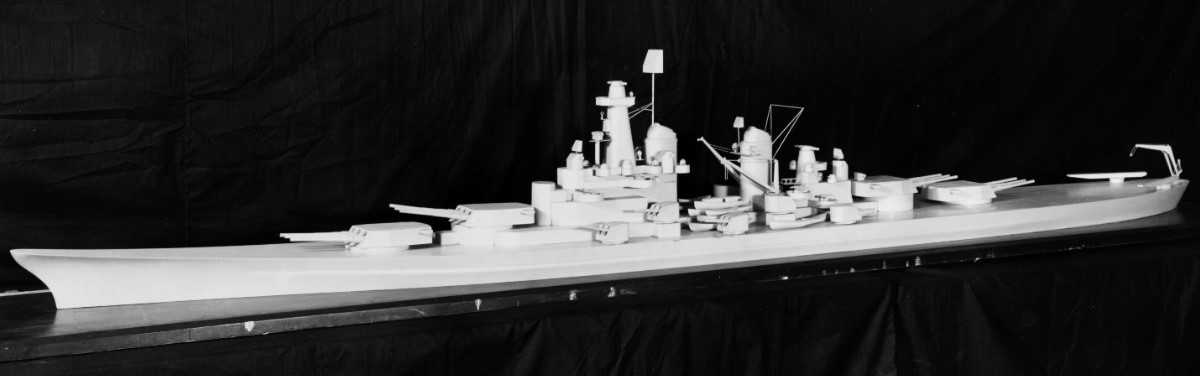

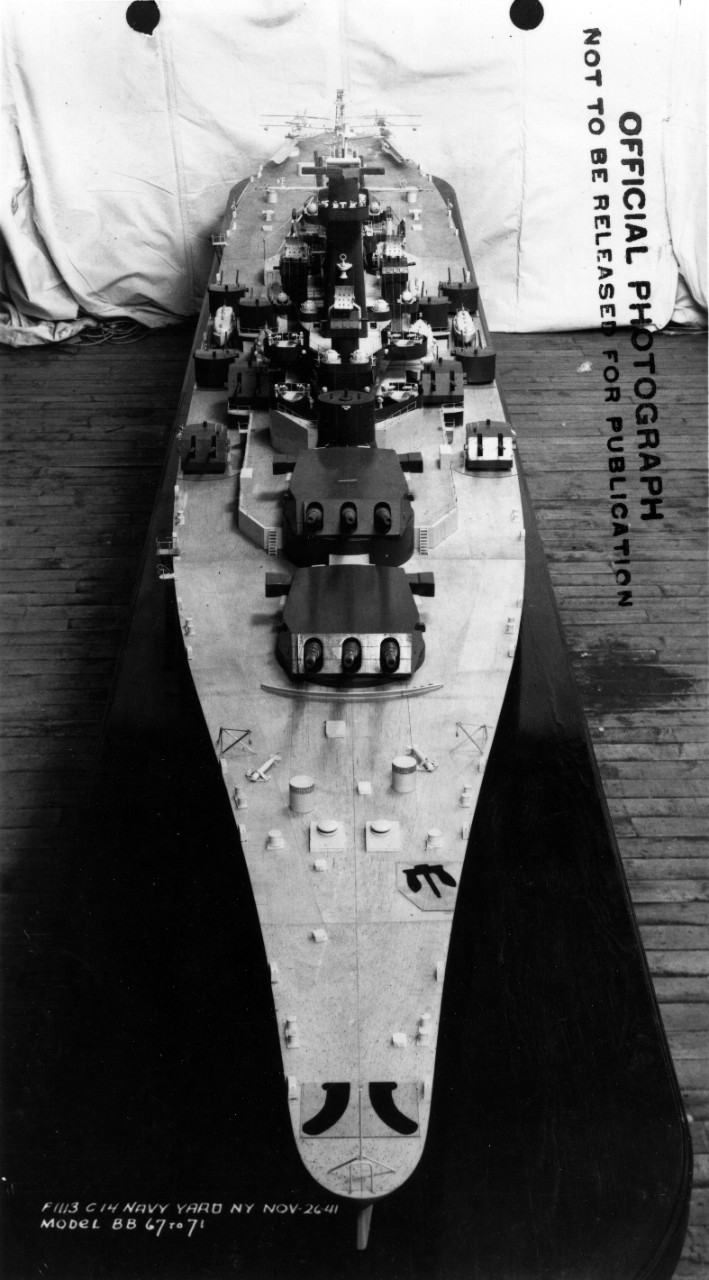

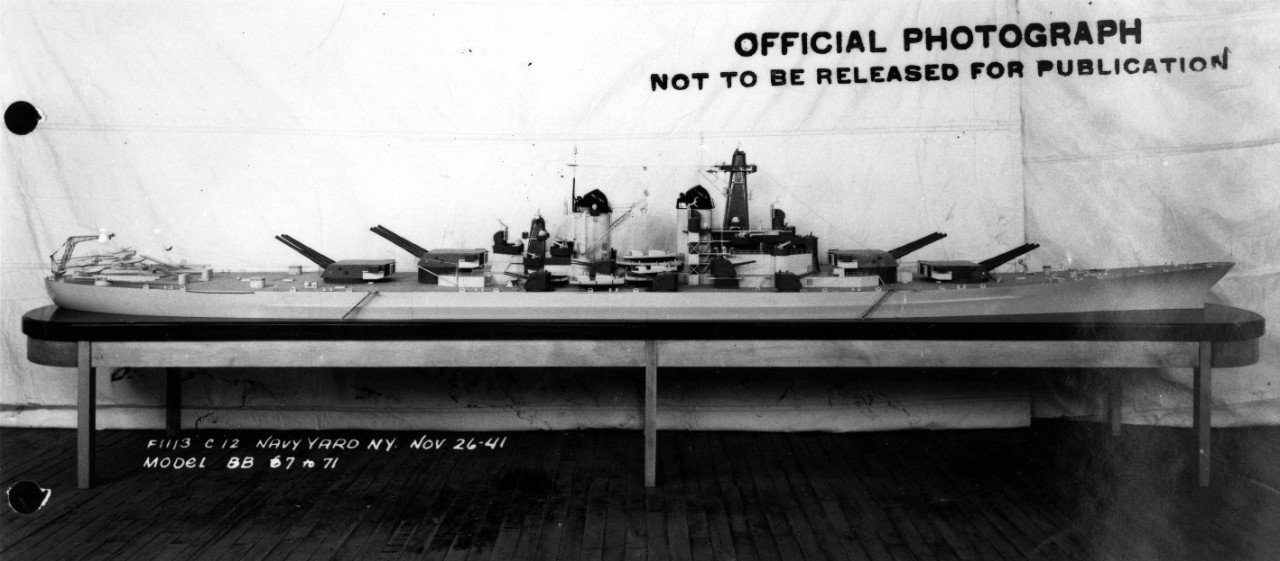

An early model of Montana

Obviously the same constraints that had been in place during the preliminary design for the Iowas still applied, so the best they could do was a 4-turret South Dakota with 50-caliber guns. To complicate things further, the development of the 2,700 lb superheavy shell had upset all of the careful balancing the designers had done, and the Bureau of Ordnance wanted to replace the 5"/38 with a new dual-purpose 6"/47 to counter bigger Japanese destroyers. The most promising scheme for saving weight was to replace the four triple turrets with three quadruple turrets, which could shorten the armored box significantly, saving 800 tons of turret weight and another 800 of hull armor. This could allow an immune zone of 18-26 kyrds against the superheavy shell, although without the new secondary guns, 12 of which would cost at least 800 tons more than 20 5"/38s. However, the quadruple turrets were risky, weighing in at 2,064 tons as opposed to the 1,622 of the triple. This might well require increased electrical power, which in turn would drive up the length of the armored box and push the design over the treaty limit. Other sketches were made focusing on protection with three triples, and the designers were able to get the desired 18-30 kyrd immune zone, using the 50 caliber gun for the belt and the 45 caliber gun for the deck.1 Preliminary Design continued to work on a series of designs with mixed quad and triple turrets, but the result looked to be at least somewhat disappointing.

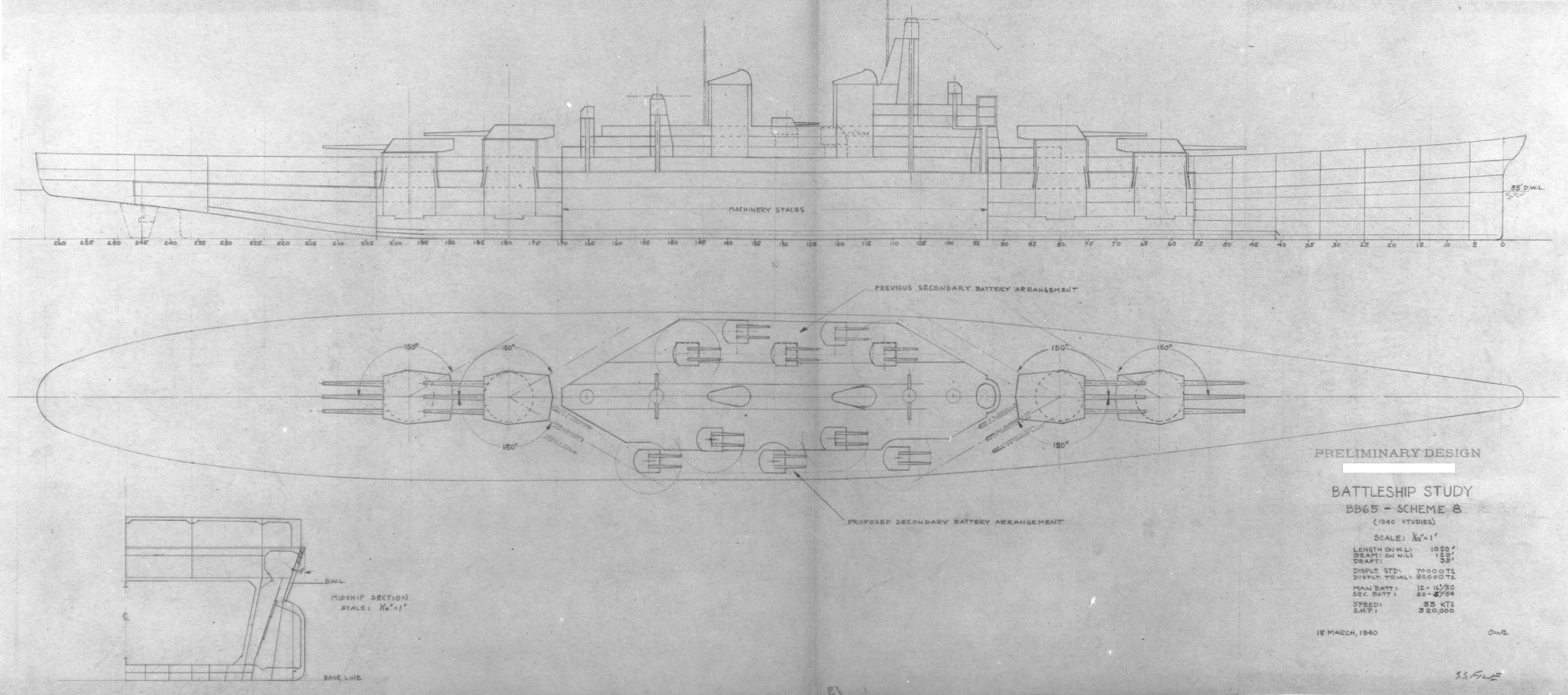

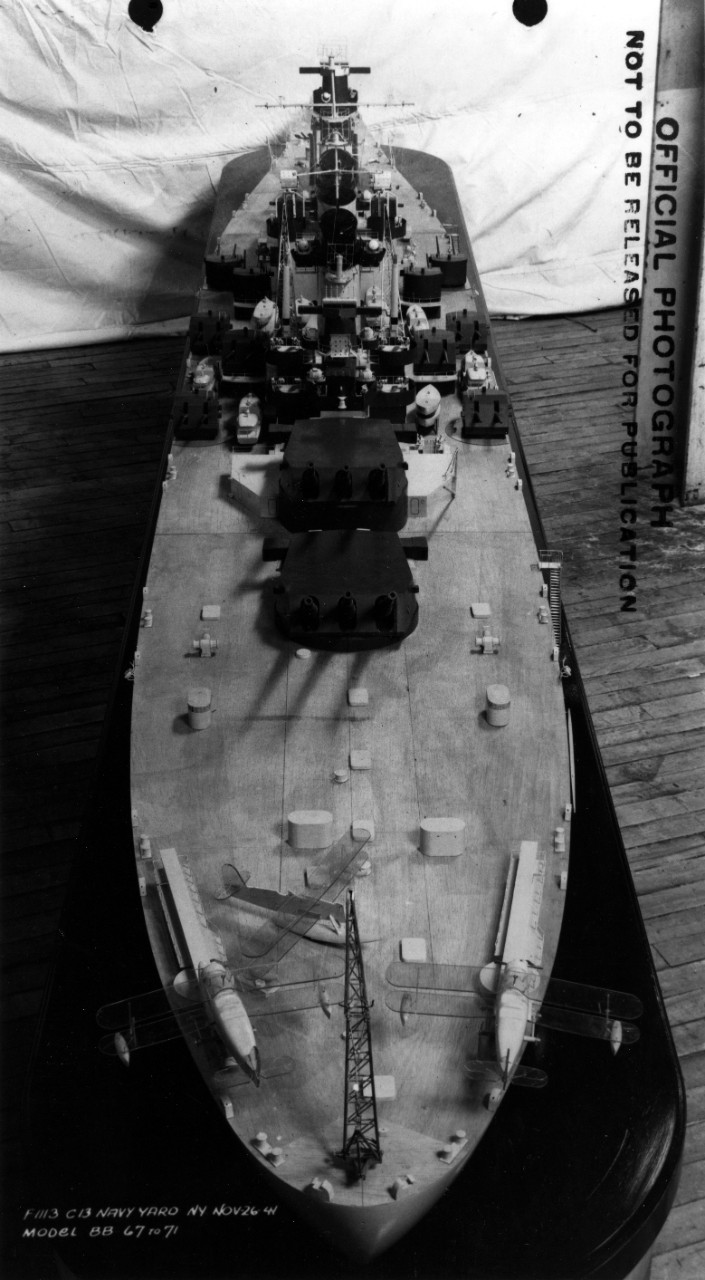

One of the largest schemes, combining heavy protection with Iowa speed

That all changed when war broke out, and the naval treaties were suspended. The General Board promptly asked for what it had really wanted all along, a ship with the 20-30 kyrd immune zone against the heavy shell, and four triple turrets. Two series were developed, one with a speed of 27.5 kts, the other capable of 32.5. The slower ship initially came in around 51,500 tons, while the faster one would have required 318,000 SHP,2 almost a third again more than Iowa, and displaced 63,500 tons. A conventional geared turbine system couldn't handle that much power, and the turboelectric drive required for it would be much bigger and heavier. At about this time, the 6"/47 was finally abandoned, to be replaced by a notional 5.4" gun. The 5.4" was never built, and the final design instead used a 5"/54 gun in twin mounts. This fired a 70 lb shell, as opposed to the 55 lb of the 5"/38, which made it more effective against destroyers, but slower and more difficult to load.

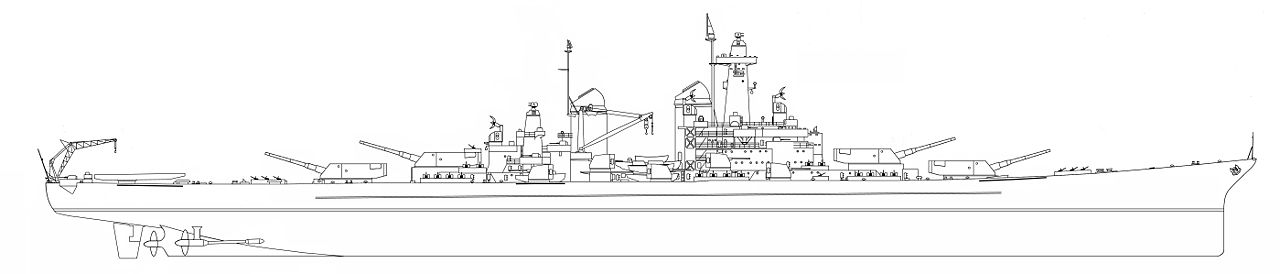

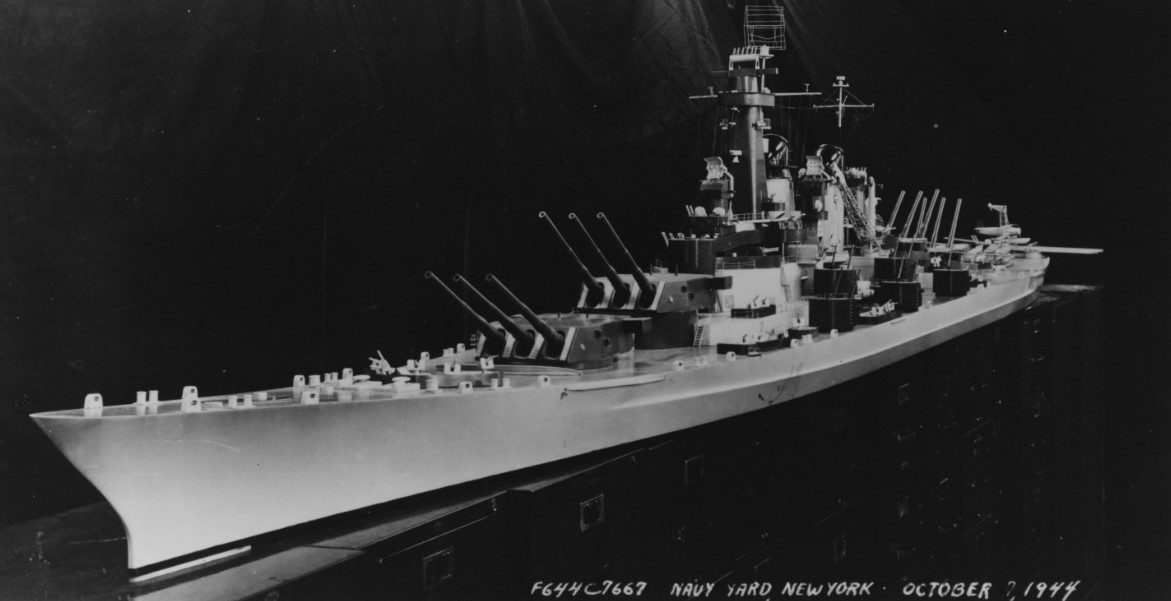

The final Montana design

These designs also saw another major constraint relaxed, that imposed on American battleships for the past three decades by the locks of the Panama Canal. This was becoming increasingly troublesome, and Congress authorized a plan to build a third set of locks, 1200' long and 140' wide. These would be specially armored and reserved for warships, as there was serious concern about an attack on the canal. Much like the Montanas themselves, the third-lock project was suspended when the US entered the war, and it lay dormant until 2006. Panama finally decided to add an even larger set of locks, which opened in 2016.

Another casualty of the abandonment of the treaty limits was the internal armor scheme initially developed on the South Dakota class. While it was slightly lighter, the internal armor was significantly harder to build and to repair if damaged, and damaged stability was a problem due to the volume outboard of the armor. The Montanas maintained the 19° slope of the previous two classes, with an underwater bulge to provide sufficient buoyancy. This drove up beam even more, due to the need for sufficient area at the waterline. The belt itself ranged from 16.1" to 10.2", with a 7.5" deck and a 2" bomb deck. The protection against underwater shell hits provided by the sloped lower portion of the internal belt was also lost. It was replaced by a separate lower belt that ran from 8.5" down to 2.5", similar to that used on the North Carolina to protect the magazines. At this point, the heavy armor over the leads to the steering gear was deleted to save weight, being replaced by armored tubes.3

The battleship plan received another shock with the Fall of France. Previously, it had been assumed that the British and French would contain the German fleet, leaving the US Navy free to face Japan. Now, France was gone and there was a very real danger that the US would have to face not only the Japanese fleet, but also a substantial fraction of the European battlefleets, all at the same time. The response was the massive Two-Ocean Navy Act, which authorized, among other things, seven new battleships, two more Iowas and five of the new ships. This in and of itself represented a victory for the General Board, as there had been serious proposals for a design freeze on the already-approved Iowa class to speed production. The Board objected, claiming that the Iowa was unbalanced and that a superior design should be adopted as soon as possible. They didn't win all of these debates, most notably with the Cleveland class light cruisers, which were produced in large numbers despite much better designs being on the drawing board.

The final design series for BB-674 began in late 1940, with a 61,000 ton ship, 890' long and with a beam of 118'. It used the same powerplant as the Iowas, but this only sufficed to drive it at slightly over 28 kts. The final design used a new powerplant, this one of only 172,000 SHP, and laid out in a manner reminiscent of the Lexington class, with two rows of boilers outboard and the turbines for the inboard shafts in the center. This allowed them to cut machinery length, which ultimately saved over 600 tons, although some of the weight was invested in increasing armored freeboard from 8' to 9'.

The ships had originally been planned to be laid down in 1941, but industrial shortages prevented it. In April 1942, Roosevelt suspended all five ships, claiming steel shortages. The General Board responded that the shortages were a matter of priorities, not capability, and that Roosevelt, who was very air-minded, was biased against the battleships. Despite their efforts, the five ships, to have been named Montana,5 Ohio, Maine, New Hampshire and Louisiana, were cancelled on July 21st, 1943. They were the last American battleships to have been designed and ordered, and with them, the story of American big-gun capital ships came to an end. The idea of building more after the war was briefly investigated, but never pursued.

1 Remember, a steeply-falling shell is better able to penetrate the deck, so the outer edge of the zone is closer in for the shorter, lower-velocity gun. ⇑

2 Shaft Horsepower. ⇑

3 The logic behind this armor is not entirely clear, and most other nations didn't armor their steering facilities particularly heavily. I may look into this at some point. ⇑

4 All previous design sketches had been for BB-65, before that number was used for Illinois of the Iowa class. ⇑

5 Interestingly, Montana is the only one of the then-48 US states never to have had a completed battleship named after it. An armored cruiser of that name had been completed, but two successive battleships were cancelled. The first was a unit of the original South Dakota class. ⇑

Comments

This seems like it will be even worse in the future. Carrier and submarine build times are now in the four year range. I wonder how that impacts the planning and fighting of a peer/near peer war.

Building large ships during a war has been off the table since the 60s, and everyone knows it. The next war will be come-as-you-are.

What was on the table that was so much better than the Clevelands? They seemed like perfectly good CLs for their weight class at the time.

That was based on a comment in Friedman's US Battleships. I did some digging, and the description of the "unlimited" (fully post-treaty) light cruiser is in his US Cruisers. It starts on p.305. The short version is that the Clevelands were incredibly tight. They didn't have enough stability and weight margin to carry the light AA guns and radar equipment the USN wanted, and they were slower than the General Board wanted. Sketches were made to rectify this, although the only ones listed in the Friedman are for ships of 13,300 tons standard, which presumably bought a lot more stability.

How does "balancing" against your own guns make any sense? You need to defend against the other guy's guns.

Even if the other guy's guns happen to be identical to yours today, after 5 years of gun/ammo improvements, your armor will be heavy and insufficient for it's purpose.

You don't know exactly what's going to be shot at your ship. It could end up in battle with HMS Furious (in a universe where the 18" guns work well), or it could spend all its time beating up cruisers. In the first case, you need a couple of tiny guns and lots of armor, while the second case could do with more firepower, but doesn't need much armor. So you have to make some assumptions about the threat. These days, we'd do it with loads of studies. (Of course, these days, we have a lot more threats.) Back then, they had to assume a gun, and for a reasonably balanced design, they chose the ship's own gun. It's not a perfect system, but it works pretty well if you're going to mount a reasonable number of guns (8-12).

The other important things to remember are that armor isn't a binary and that all heavy guns more or less work on the same scale. Yes, there is some variation in terms of things like muzzle velocity vs shell weight (deck penetration vs belt penetration, to a first approximation) but it wasn't like a newer and better gun was going to render your armor scheme entirely ineffective. A ship with protection designed against 14" guns is still going to be resistant to 16" weapons, it's just going to have a smaller immune zone. And that can change a lot, too. Maybe the shell is coming in from significantly off the beam, which means the belt blocks it just fine.

Heavy and insufficient? Aren't these mutually exclusive? Either you need more armor (the KGV, for instance, had essentially what the US would consider 16" protection) or you need less so it's lighter.

I'm trying and failing to picture Montana's armor scheme. Is it an armored hull that slopes 19 degrees inward until it meets a bulge?

Pretty much. There's a diagram of the scheme here.

oh gotcha, thanks. So I guess they just assumed any long range hits below the belt would be too high angle to do anything but burst in the torp defense space.

Not necessarily. There's the 8.5" secondary belt well behind the main one to take care of any shells that hit just at the waterline. The basic logic is similar to that on Iowa, but in a ship large enough to pull off a different arrangement, and with a better understanding of how the armor affects the underwater protection.