Before WWI, both the British and German navies expected that the war's early days would see a massive clash of their fleets, a "New Trafalgar" that would decide control of the sea at a stroke. This was not to be, as the Germans, eager to avoid a battle with the stronger British fleet, stuck close to their bases in coastal waters that the British avoided due to the threat of mines, submarines and torpedoes. The only way for the two sides to meet was if one of them knew in advance where the other would be, and the British, thanks to the capture of German codebooks early in the war, had set up an organization to intercept and decode German signals, and it was this organization, Room 40, that would trigger the Battle of Jutland.

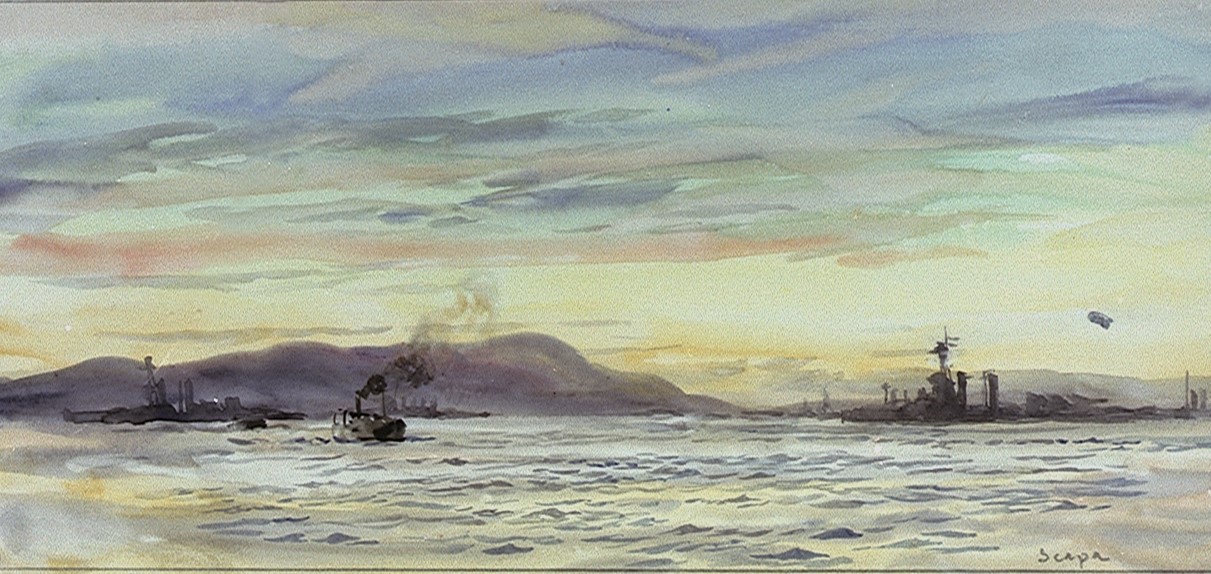

British battleships in Scapa Flow

Signs of what was to come began to accumulate in mid-May, as the Germans dispatched 18 U-boats to lie off British bases in hopes of catching the Grand Fleet as it sortied. The Germans, unconcerned with the threat of British interception, coordinated the sortie, including the U-boats themselves and the minesweepers necessary to get them to sea, via radio. But none of them headed for the trade routes bringing vital supplies to Britain, giving Room 40 a clear sign that something was afoot.

Evidence of something specific began to arrive on late on May 28th, when Room 40 received a signal from Scheer ordering the High Seas Fleet to "special readiness", followed the next afternoon by a request to one of the U-boats for information on how deep it could reach into the Firth of Forth, where Beatty was based. On the morning of the 30th, the High Seas Fleet was ordered to assemble in the outer roads of Wilhelmhaven by 7 PM that evening, and a signal was sent to the U-boats, warning them to expect their fleet would be at sea. Or at least that was what Room 40 thought it said. It was sent in a new codebook, AFB, which the British hadn't captured,1 and thus had to work out from context what each group meant. Fortunately, it was designed so that the same table handled encoding and decoding, and thus the code groups were in alphabetical order. The signal meant to expect either their own fleet or the enemy fleet at sea, and while the later turned out to be correct, it didn't really matter. The Germans were clearly going to sea, and word was quickly passed to Beatty and Jellicoe to make ready.

More signals came in throughout the 30th. At 1536, Scheer signaled "On 31 May Most Secret 2490", clearly referring to written orders which Room 40 had no way of reading. But his intentions would have been completely clear an hour and a half later when he signaled that the lead ship of the 3rd Battle Squadron would pass the outer lighthouse on the Jade at 0330 the next morning, followed by the 2nd and 1st Squadrons. This signal also contained instructions for Wilhelmshaven Dockyard to start using callsign DK, which Scheer used when in harbor, to frustrate British direction-finding measures. Unfortunately, this particularly signal was enciphered using a key that Room 40 wouldn't work out until the next afternoon. But they were able to read another signal a few minutes later, which instructed the pre-dreadnoughts of the 2nd Battle Squadron leave their prize crews at home, along with one transferring command of the radio network to the Commander-in-Chief, standard procedure when the Germans went to sea.

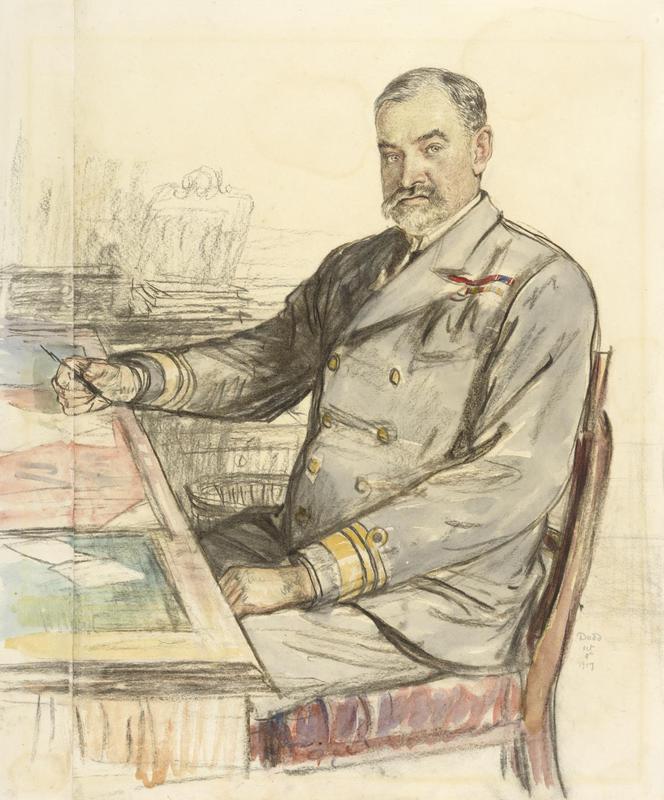

Henry Oliver

Although Room 40 was still essentially a cryptographic bureau and lacked the operational intelligence function that would be so successfully performed by the OIC during WWII, its personnel had worked out what was coming, and passed word to Rear Admiral Henry Oliver, Chief of the Admiralty War Staff. Oliver was the official head of Room 40, and the man responsible for passing information from it to the commanders afloat. Even though this was far too much work for one man, particularly a man with his other responsibilities, Oliver did a magnificent job. But this day, he made a mistake, focusing on the possibility that the German 2nd Battle Squadron would attempt to rush the Dover Strait. The only British forces available to counter were the pre-dreadnoughts of the British 3rd Battle Squadron based in the Thames Estuary, which would need destroyer cover. As a result, Reginald Tyrwhitt's Harwhich Force, which had handled the bulk of the coastal fighting from the time of Heligoland Bight onward, was kept back instead of sailing to join Jellicoe as planned. Tyrwhitt put to sea on his own initiative when the Germans were sighted on the 31st, but Oliver recalled him, still fearing an attack on the Channel.

Orders to sail went to Jellicoe at 1740, and by 2230, his entire fleet was at sea, with Beatty's following half an hour later. Hipper and Scheer wouldn't sortie until the early hours of the next morning. But while this was a triumph for Room 40, the limitations of the organization were also being sharply exposed. First, Jellicoe believed that the battlecruiser Hindenburg and the two Bayern class battleships had already joined Scheer, because Room 40, who had a very accurate understanding of the High Seas Fleet's strength, wasn't allowed to look over intelligence reports going to him for fear of compromising the operation. Second, Room 40 didn't actually know what the Germans were up to, and as a result the British battlefleet was dispatched to a rendezvous off the coast of Denmark, presumably in hopes of catching the Germans on their way home. But the Germans decided to call off their raid on the British coast due to problems with their Zeppelins, and turned to sweep the Skaggerak, between Norway and Denmark.

Thomas Jackson

And it was around noon on the 31st that things began to go really wrong. Thomas Jackson, the Director of Operations, dropped by Room 40. He was an unpleasant character, narrow-minded and uninterested enough in Room 40's operations that one of his two previous visits to the organization had been when a key change stopped decrypts from being passed out for a few days "to express his pleasure that he would not be further bothered with this damned nonsense".2 Jackson asked where the direction-finding system currently placed callsign DK, which Scheer used while in port, but which was transferred ashore when the fleet sailed to confuse the British. Room 40 was aware of all this, but instead of trying to explain what was going on to Jackson, they simply told him it was still in Wilhelmshaven and sent him on his way. Oliver quickly sent a signal to Jellicoe and Beatty that read in part "It was thought Fleet had sailed but Directionals place flagship in Jade at 11.10 am GMT. Apparently they have been unable to carry out air reconnaissance which has delayed them." Three hours later, Beatty sighted Hipper's battlecruisers, while Jellicoe was sill some ways away, having chosen an economical speed after receiving the signal. This cost valuable daylight before the Grand Fleet could engage, and undermined both men's trust in the information they were receiving from shore.

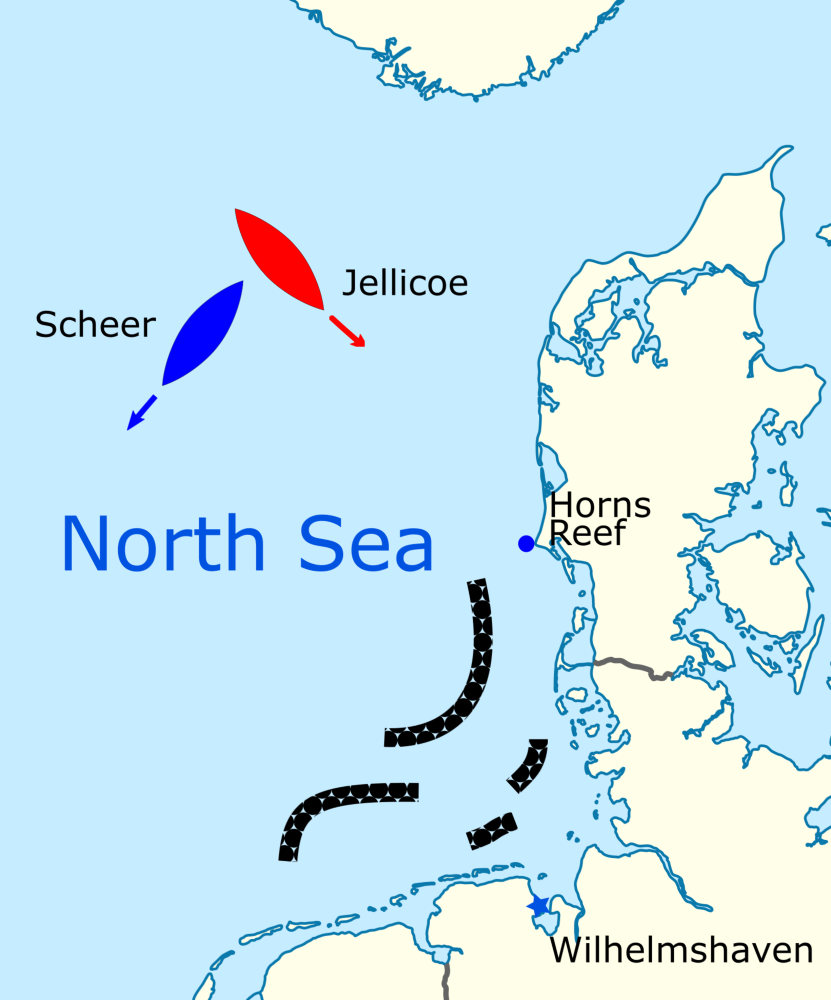

This wasn't a problem during the rest of the daylight action, as Room 40 got little information, none of it particularly useful, and Jellicoe made the right call at the critical moment, placing his fleet between Scheer and his routes home. But as night fell, Jellicoe settled down, hoping to be in a position to bring the battered High Seas Fleet to battle at dawn. He guessed that Scheer would head south, towards the direct entrance to the Jade Estuary, but the Germans instead turned southeast, towards Horns Reef off the coast of Denmark. Information to this effect began to pour into Room 40 starting at 2225.3 The first was a message from a German destroyer giving the location, course and speed of the rear of the High Seas Fleet, passed to Jellicoe around 2300. Unfortunately, the position given didn't make sense to him, either due to German navigational error or just general confusion, destroying any remaining faith in the dispatches from shore even as the flood of information indicating that Sheer was headed for Horns Reef came in.

The situation at 1940. Dots are minefields.

Even as Jellicoe was receiving that message, Room 40 made its next decrypt, an order from 2214 to the rear battleships of the High Seas Fleet, instructing them to make a course straight for Horns Reef. It was passed to Jellicoe around 2340, but had no effect. Fifteen minutes later, another signal was decoded, a request from Scheer for a Zeppelin reconnaissance of Horns Reef at dawn the next morning. This should have been incontrovertible evidence of the German intentions, but for some reason Oliver didn't pass it to Jellicoe, probably because he was dropping out to nap, leaving Jackson in charge. In total, only 3 of the 16 messages that came from Room 40 to the Operations Division during the night of May 31st/June 1st were passed to the Grand Fleet as the High Seas Fleet got past the Grand Fleet and made its escape. If this information had reached Jellicoe even as late at 0215 on the 1st, he could have caught the Germans and done a tremendous amount of damage, reversing the immediate response to the battle and allowing the British to claim a victory at the time, instead of in the court of history.

But that was hardly Room 40's fault. They had enabled the battle to be fought in the first place, and had managed to provide actionable intelligence during the night, an advantage squandered by a poor system for turning their intelligence into information in the hands of the combat commanders. The British would learn from their mistakes, building a better apparatus for distributing the signal intercepts in the last years of the war, and refining it to become a key weapon during WWII.

Comments

The last image seems to be mislabeled;it has Jellicoe going southeast towards the Horns Reef, contradicting the text.

It's correct for that exact point of time, stolen from the main Jutland series. Later, both would turn south, and Scheer would later make for Horns Reef. I've been busy and didn't want to redo illustrations.

Excellent! I am so glad I stumbled upon your website, its an absolute treasure trove of fantastic articles. Thank you.

Is this supposed to read 'Jackson'?

It is not. Jackson passed the information to Oliver, who drafted the signals being sent out.