By the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, Russian naval policy was in turmoil. Their defeat in the Russo-Japanese War had thrown the government and the navy into chaos, as well as wiping out the Baltic Fleet, Russia's main overseas force. The arrival of the dreadnought didn't help matters, rendering the remaining pre-dreadnoughts obsolete. The end of the war saw the establishment of the Duma, the Russian parliament, which brought outside oversight into the picture for the first time. There was widespread distrust of the so-called Tsushima Ministry,1 which had supposedly lost the Russo-Japanese war. At the same time, the Army, wary of the increasing power of Germany, began to push for a bigger share of military spending. For several years, these factors stymied any plans to build dreadnoughts, and the first class of new Russian dreadnoughts was only pushed through due to some rather exotic legal maneuvers.

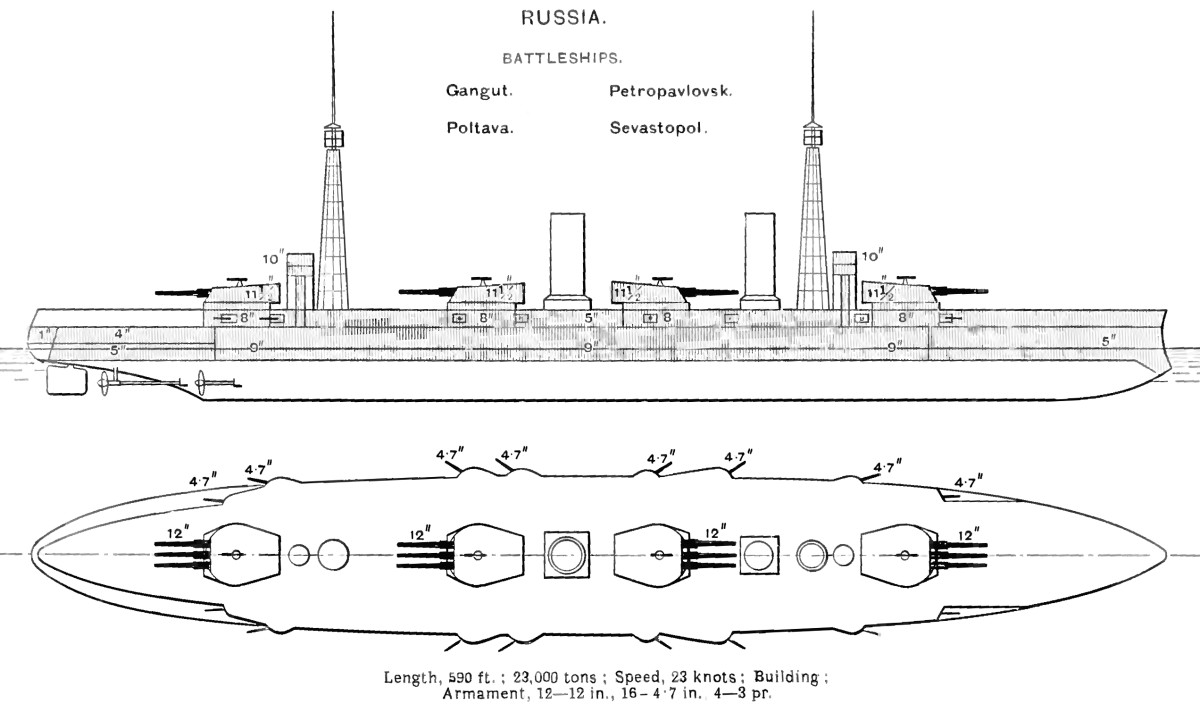

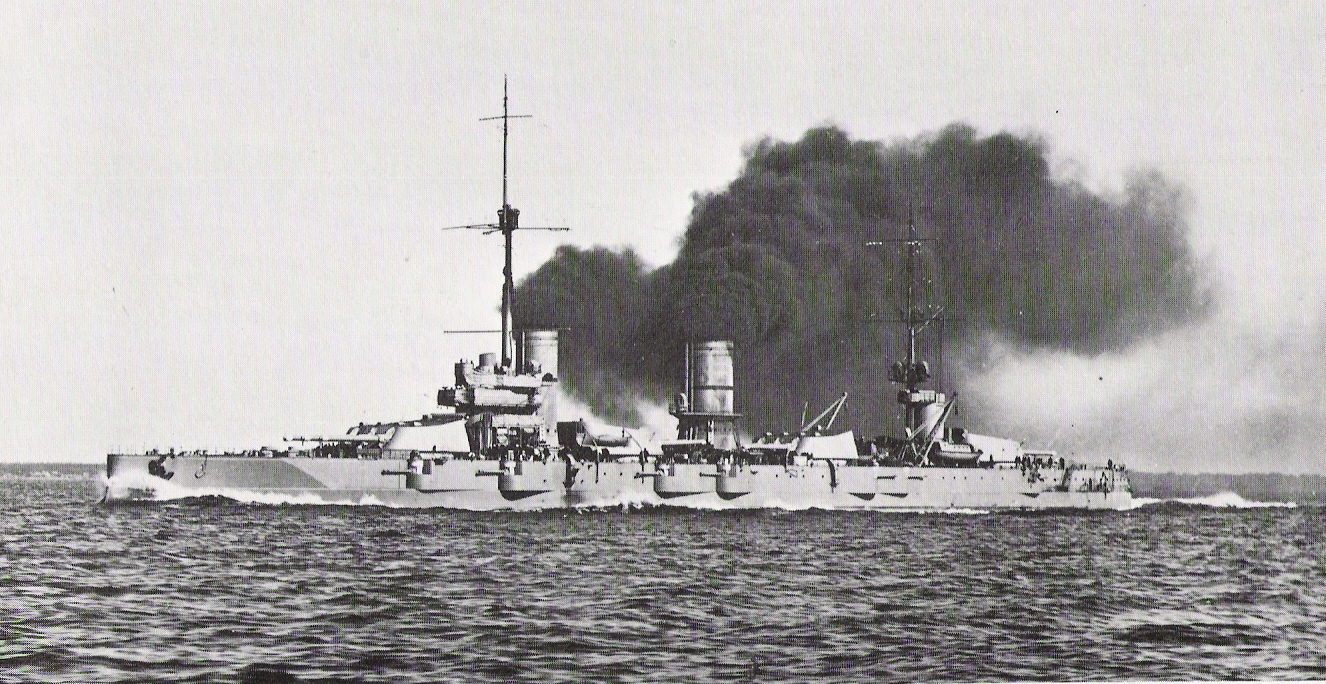

Gangut, name ship of Russia's first class of dreadnoughts

In 1911 the Duma began to reverse course. The Russian economy was booming, becoming the fourth-largest in the world by 1914. The last vestiges of the Tsushima Ministry had been swept away, restoring the Duma's confidence in the Navy. Most importantly, increasing tension with the Turks, who controlled the straits through which most of Russia's exports flowed, lead to a greater appreciation of the need for a large fleet. In 1912, an even larger shipbuilding program was authorized, combined with a strengthening of the fixed defenses of St. Petersberg to free the Baltic Fleet to operate away from the capital in time of war.

The first round of Russian dreadnought designs, dating back to just after the war, had been fairly conventional, with five or six twin 12" turrets, a speed of 21-22 kts, and a displacement of about 20,000 tons. One set of designs is of some interest, though. Inspired by the elliptical hull of the former imperial yacht Livadiia, constructor E.E. Guliaev proposed a shallow-draft battleship with a large beam. The outer edges of this space were kept empty and heavily compartmentalized, a concept that anticipated the development of the torpedo bulge by almost a decade. The Duma refused to authorize any ships at that point, however, and another round of designs began in 1907.

Poltava's hull under construction

This competition eventually lead to the Sevastopol or Gangut class,2 but not without several distinctly Russian twists along the way. Responsibility for new designs was split between the MTK, the technical committee, and the MGSh, the general staff, and the two bodies often disagreed, resulting in a constant revision of various features of the proposed designs. In mid-1907, the Russian ambassador to Germany reported that new German dreadnoughts would have triple turrets. This wasn't the case, but the Russians specified triples anyway. In the later part of the year, Vickers, one of the leading British battleship builders, came close to selling a pair of ships with two superfiring triple 12" turrets at each end, but the contract was thwarted by political opposition to Vickers. That December, a competition was announced to every major shipyard on the planet, which drew a total of 51 responses, ranging from the boring to the insane.

Cuniberti's 18-gun ship3

The best representative of the latter type is a design by Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti, a man often (but erroneously) given credit for inventing the all-big-gun ship. He proposed a ship with 18 12" guns in triple turrets, with two abreast on the forecasle, two abreast amidships, and two superfiring aft. It appears that not even the Russians took this seriously, as it would have been structurally nightmarish and had a weak broadside relative to the number of turrets carried.

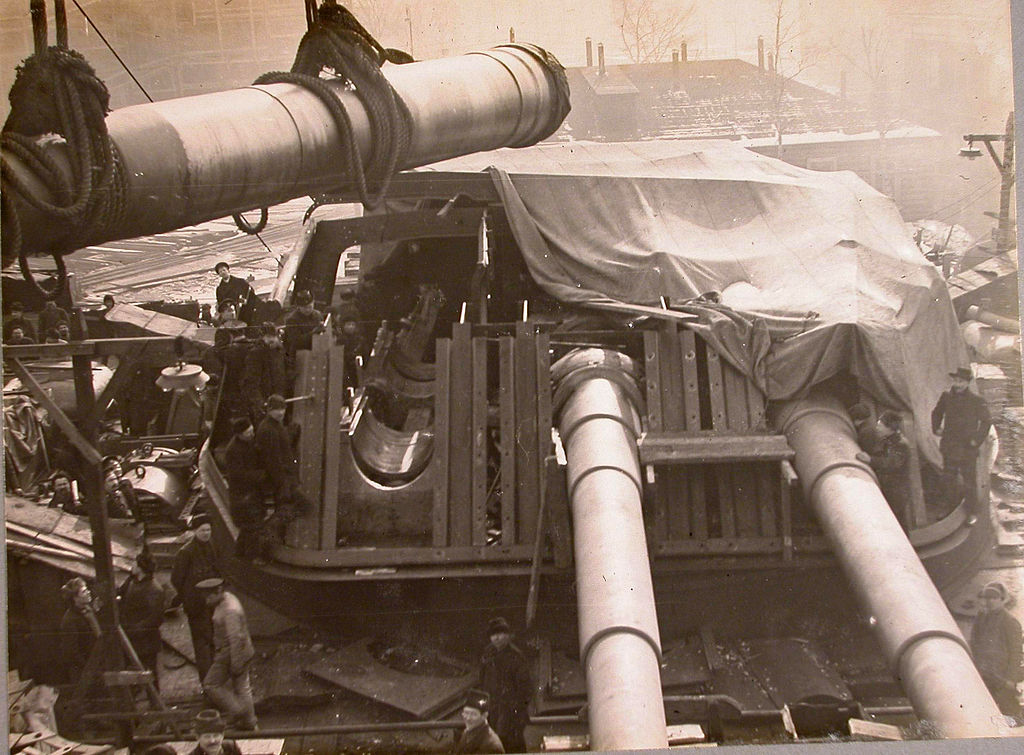

One of Poltava's turrets under construction

The Russians finally decided against the use of superfiring turrets. Like the British, they mounted sighting hoods on the tops of their turrets, limiting fire within 30 degrees of the centerline for the upper turret. It was believed that the midships turrets could fire within 20 degrees of the centerline. The "linear" arrangement also meant lower topweight, reduced stress, a reduced risk of a hit taking out multiple turrets, and a lower silhouette. The main disadvantage was that it meant the turrets and machinery were intermingled, and forced steam lines to be run around the magazines.4 To make that problem even worse, MGSh wished to mount the turbines between two sets of boiler rooms, although MTK wasn't a fan of that. There were also problems with blast on deck, which made the secondary battery arrangement problems worse. One useful innovation in machinery was the adoption of transverse coal bunkers on the ends of the boiler rooms. This meant that the coal bunkers along the sides of the ship could be secured, greatly increasing underwater protection. 540 tons of coal was provided, enough for 18 hours at full speed.

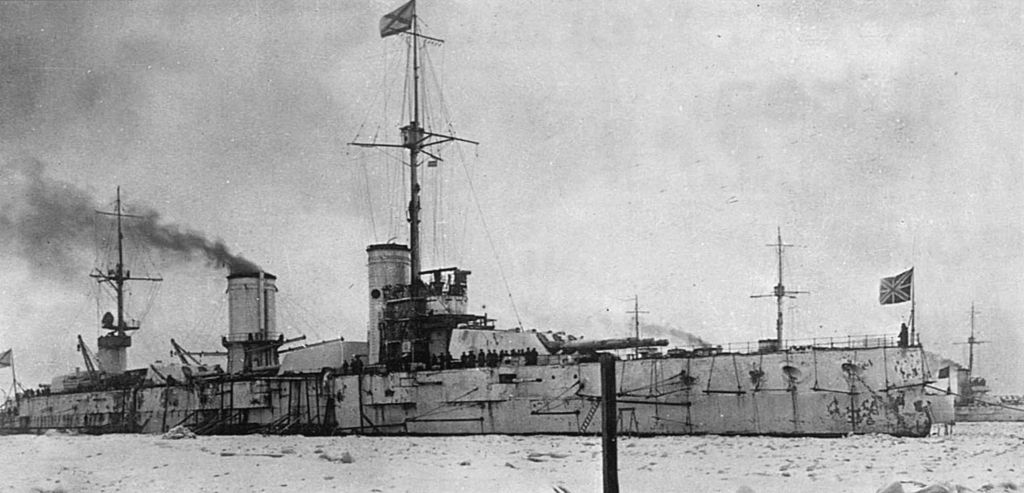

Petropavlovsk in Helsinki, cWWI

The Russians came very close to buying the design of German shipyard Blohm und Voss, until outrage from their French allies forced them to switch to a native design from the Baltic Works. Before the final revision, MGSh and MTK had another dispute. MGSh wanted to add more armor, increase in speed from 21 to 23 kts, fit 100mm instead of 120mm secondary guns, and add diesels for increased cruising range. MTK fought most of these off, on secondary armament by noting that it would be more expensive to buy the 100mm because the 120mm was already under contract. They finally lost on speed after MGSh packed a committee meeting with officers in favor of small-tube boilers, which MTK's engineering section had resisted. Life was made more difficult for the designers because the turrets and ammunition had not been completed when the ships were laid down. MGSh also requested at the last minute that the secondary guns be retractable behind heavy armor, which would have been enormously complicated, and was thus not adopted.

Poltava being launched

Construction did not go smoothly, either. The ships were laid down in June of 1909, but work didn't really begin until September. The Duma was being difficult with funding, and the shipyards had to do a fair bit of work with their own money. Contrary to western reports, work was never suspended due to doubts about hull strength. In May of 1911, the Duma finally released funding, and all four ships were launched later in the year. The turrets remained problematic, and were not completed until 1914. Even before the outbreak of war, work was proceeding around the clock to get them completed, and they joined the fleet at the end of year.

Despite extensive use of high-tensile steel, usually reserved for destroyers, the Ganguts were considerably overweight, completing about 1,400 tons over their 23,300 ton design displacement. They floated about 16" deeper than designed, cutting their planned 20'4" freeboard considerably. This, combined with a slight trim by the bow, meant that the forward casemate guns were unusable in even moderate seas.

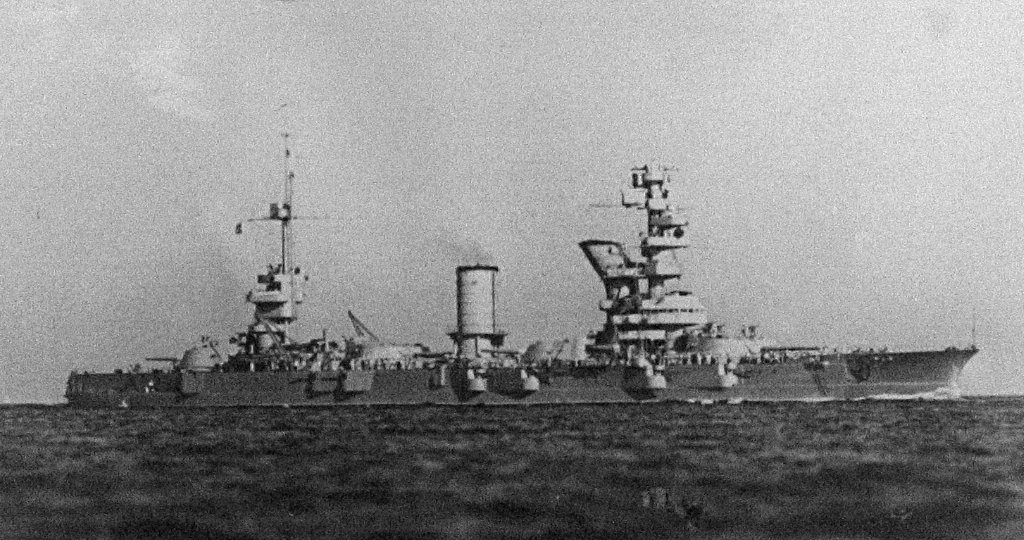

Gangut in 1943

As you'd expect when talking about Russian battleships, there were changes while under construction. The 12"/52 guns were originally designed to fire a 385 kg shell at 915 m/s. However, long-range gunnery trials resulted in the switch to a 471 kg shell at 762 m/s. The turrets and magazines needed major changes to support the longer shells. This caused extensive rework to the ships after the changes were ordered in 1911, and made the shell rooms very cramped. It was estimated that 60% of shells couldn't be accessed quickly enough to keep up the desired rate of fire. The 16 casemated 120 mm guns were sited to give at least four on each bearing, but due to overloading were much too low to be fought effectively. A quartet of underwater torpedo tubes completed the armament.

The Russo-Japanese War left the Russians with a deep appreciation of the power of the high explosive shell, which left the Ganguts with an armor scheme optimized for a very different threat from that faced by the all-or-nothing armor schemes the US adopted a few years later. The ship was armored throughout against HE fire, which meant a thin belt, only 9". The belt was backed by a series of 2" splinter bulkheads designed to capture the broken shells. It would probably have been effective against the AP shells available at the time the ships were designed, but the improved post-Jutland shells would have penetrated fairly easily. 3"-5" plating was used across much of the rest of the hull. The protection for the armament was pretty lacking, with 6" barbettes and 8" turret faces and sides. The upper deck was 1.5", with a main deck of 1". All in all, it was an intelligent system for the conditions the Russians expected to face at the time, although it probably wouldn't have worked very well if they'd seen combat later in their careers.

Poltava complete and at sea

One weakness was the total lack of torpedo protection, which was rejected on weight grounds. In theory, the ship had sufficient subdivision to survive any given torpedo hit, with the 25 small-tube boilers divided into four compartments, split around the second turret. The turbines, between turrets 3 and 4, were in three rooms, with a total of 10 driving four shafts.5 The standard "top speed" was 21.75 kts at 32,000 hp, although on trials, Poltava reached 24.1 kts at 52,000 hp. They were rather short-legged, limited to 3,500 nm at 10 kts.

All four units of the class first served in the Baltic, though none saw major combat during WWI. Their crews participated in the February Revolution, and they subsequently entered Soviet service. All but Petropavlovsk6 were laid up in 1918, and Poltava was badly damaged by a fire. She served as a spares ship until being broken up in 1949. Gangut and Petropavlovsk fought in the Siege of Leningrad during WWII, with Petropavlovsk suffering an explosion of the forward magazine due to German bombs, and being used as a floating battery throughout the rest of the war. Sevastopol was transferred to the Black Sea in 1930, and fought briefly in the Black Sea. She and Gangut were struck in February of 1956, some of the last first-generation battleships still afloat.

Sevastopol after WWII

While the Ganguts are by far the most famous and successful of the Russian dreadnoughts, they were not the only all-big-gun ships planned by the Tsar's Navy. We'll look at the others next time.

1 Named after the Battle of Tsushima, the main naval battle of the war. ⇑

2 The etymology of these ships is confusing because they were renamed by the Soviets several times. Gangut is the standard name in most reference books. ⇑

3 Yes, I did the illustration myself. No, I don't have any artistic talent. ⇑

4 This heated the powder, which increased muzzle velocity, reducing accuracy. It also increased the risk of a powder detonation. ⇑

5 Each wing shaft had a separate room, with an HP ahead and an HP astern. The center shafts shared a room, with an LP ahead and astern, and an HP cruising turbine each. ⇑

6 I'm going to continue to use the original names here. Wiki has details on the careers of each ship. ⇑

Recent Comments