May 31st, 1916 saw the Battle of Jutland, the greatest clash of battleships in history and the only time the British and German main fleets fought each other. As befits such an interesting and pivotal battle, I've written a long series on it, but for the benefit of those who don't want to wade through all seven parts, I thought it appropriate to write a single-part summary.

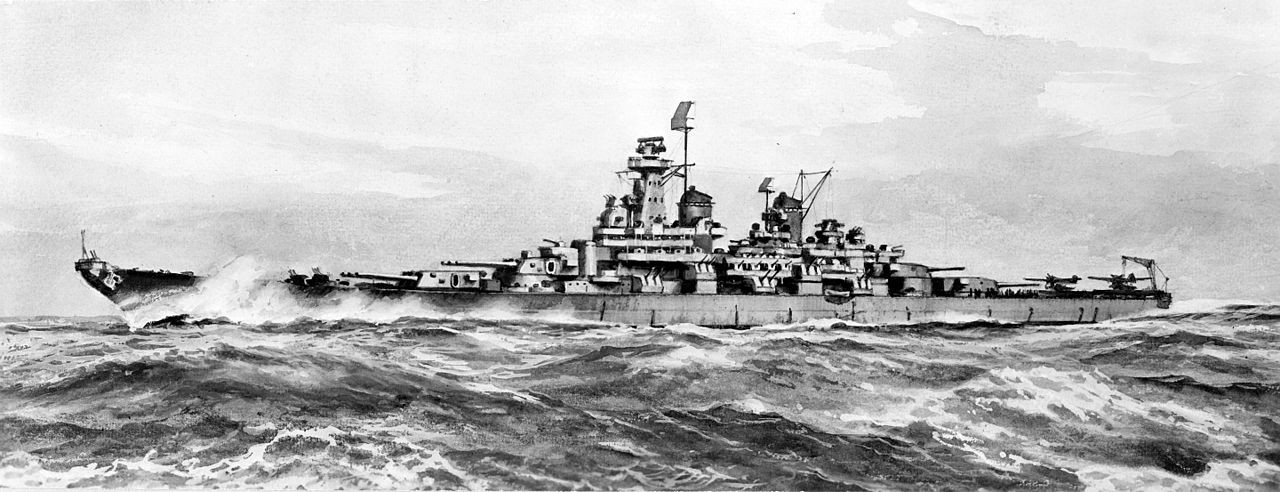

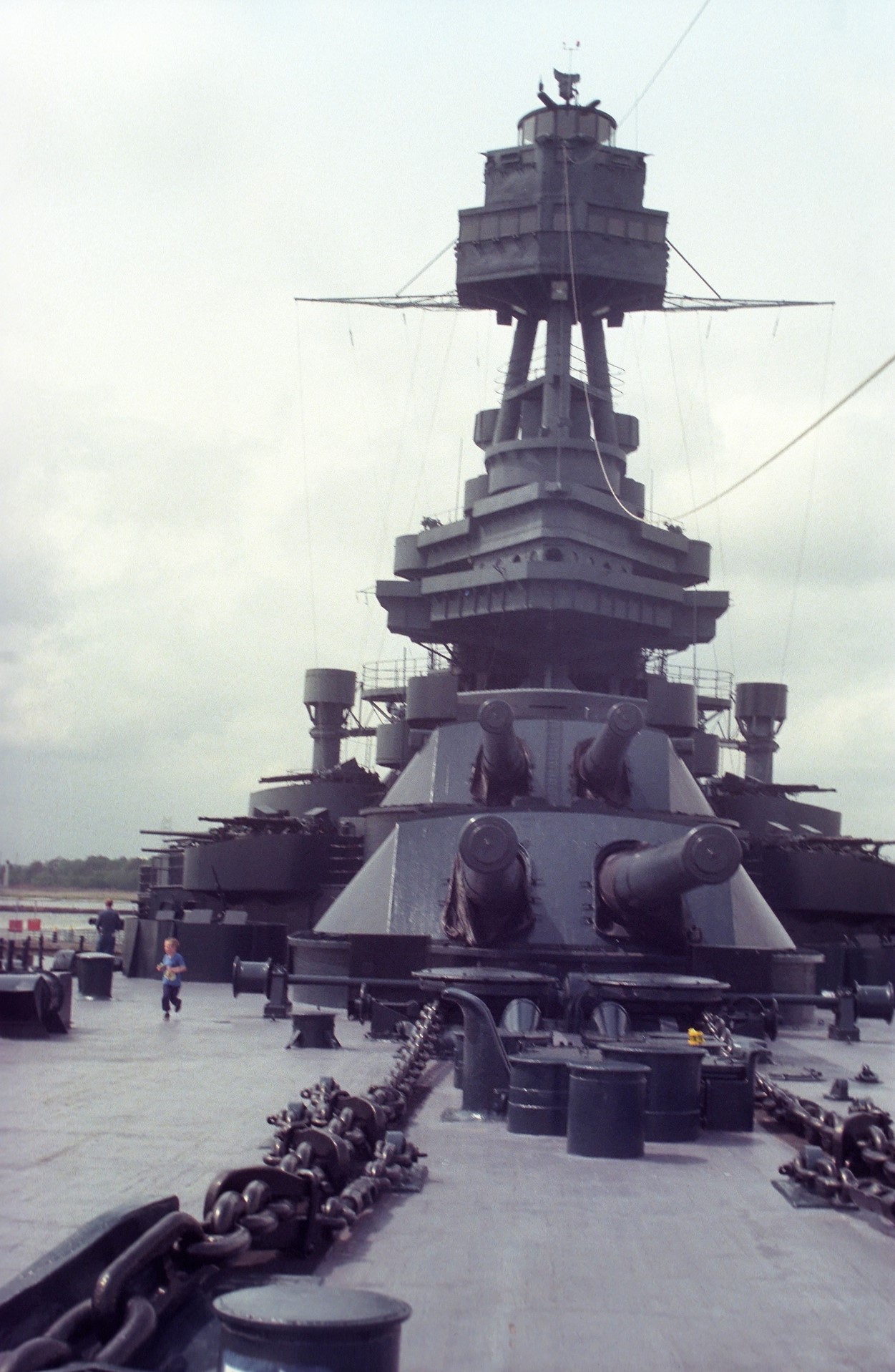

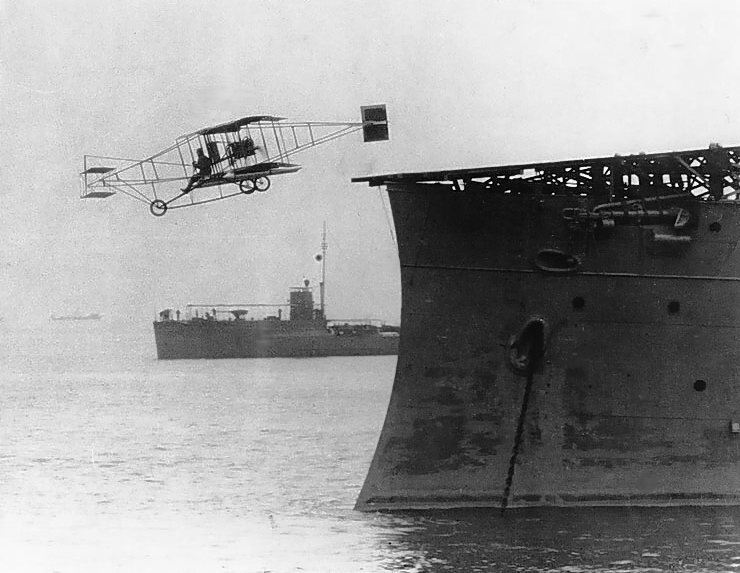

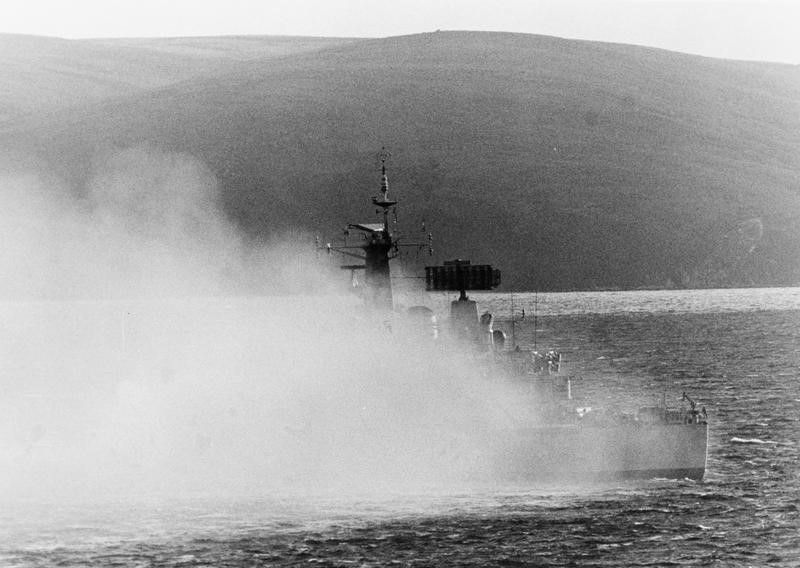

In the runup to WWI, the British and the Germans had built huge fleets of battleships, spurred on by the Kaiser's love of shiny toys and the British understanding that the loss of maritime supremacy would be catastrophic. In 1914, the British, who had outbuilt their rivals, instituted a blockade of Germany, plugging up the exits to the North Sea with the Scotland-based Grand Fleet. The Germans, hoping to wear the larger fleet down, attempted to use raids to draw out detached elements and crush them with the High Seas Fleet. By mid-1916, the only result had been a few indecisive battlecruiser engagements, and both sides wanted action. Read more...

Recent Comments