The battlecruiser did not spring fully-formed from the mind of Jackie Fisher. In fact, Invincible was very much in the mold of armored cruisers that had gone before her, although the incorporation of the logic of Dreadnought into her design has often obscured this.

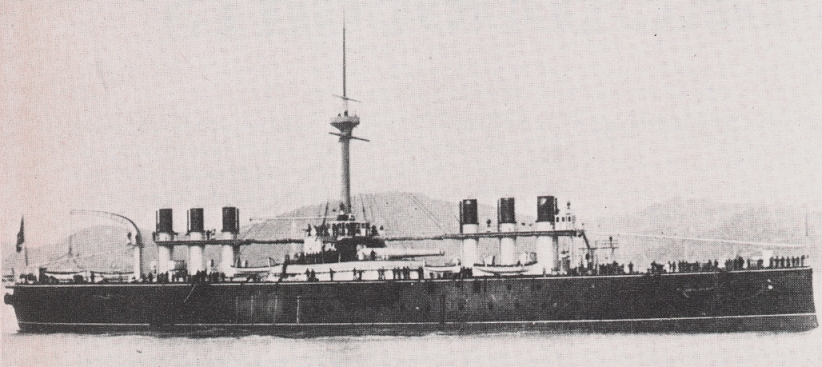

Italia

It's worth taking a closer look at the predecessors to the battlecruiser, which we can broadly define as fast ships of battleship size, designed to be capable of standing in the line of battle and of raiding or protecting commerce. It could even be argued that Warrior herself meets this definition, designed for 13.5 kts at a time when 10 or 11 was standard, although the trends become more obvious after the demise of sails in the mid-1870s. The first vessels that are clearly in the battlecruiser mold are the Italian Italia and Lepanto, by far the largest (13,700 tons) and fastest (17.5 kts) ironclads of the day and armed with massive 17" guns, but protected only by an armored deck, as used on contemporary protected cruisers. This proved a major liability when the QF gun entered service a few years later, as their sides would easily be riddled by such weapons. Read more...

Recent Comments