For Memorial Day Weekend, Lord Nelson and I went to Kansas City, and while we were there, we visited the National WWI Museum, which is in Missouri for some reason. As you probably would expect, this wasn’t the best time to visit, because the crowds were much larger than the museum could gracefully handle.

Me with the dedication, including an admiral I'm not particularly fond of1

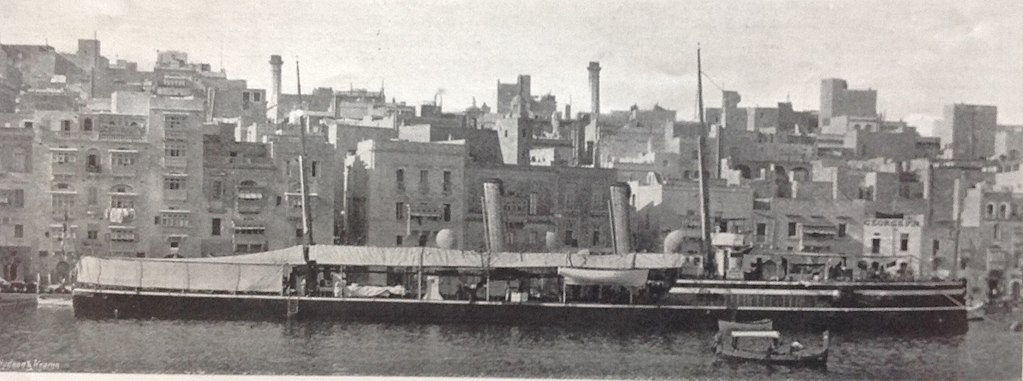

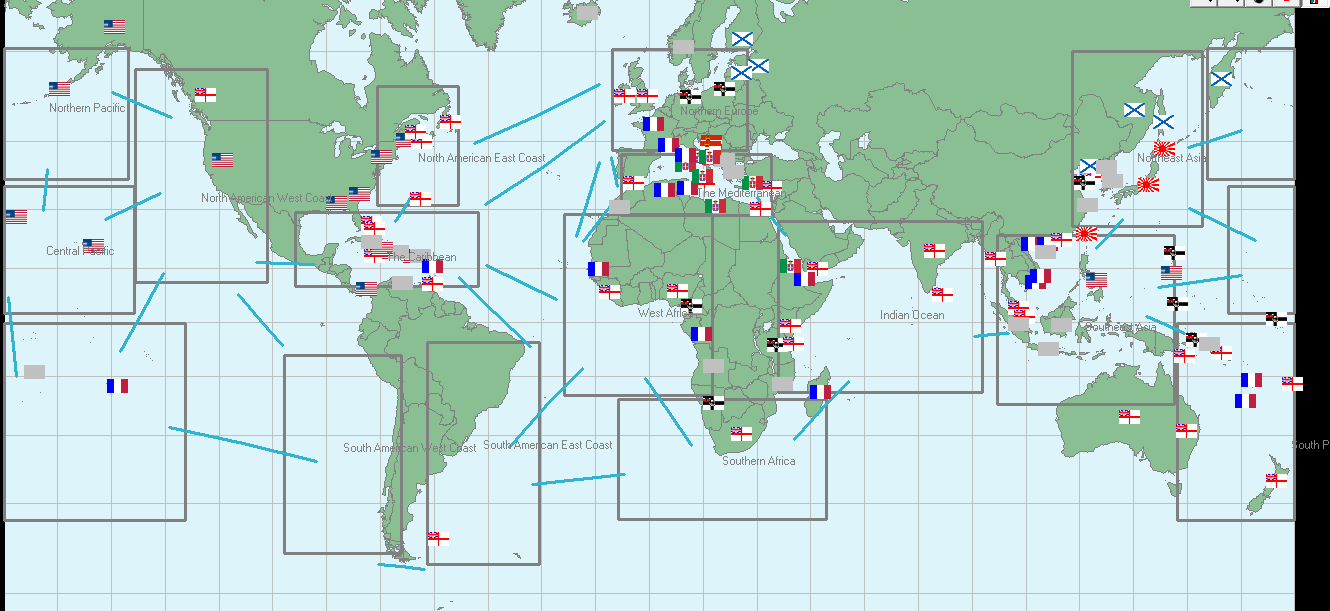

Overall, I was disappointed in the museum. It wasn’t that it was an awful museum. On the surface, they did a great job. The displays looked cool, everything was well-presented, and there were some neat interactive exhibits. But it seemed like every time they were presented with a choice between the easy route of going more in-depth on the pop-culture understanding of the war or actually challenging that narrative, they took the easy route. Lots of cases of uniforms, weapons, and other personal kit, which are easy to source and easy to explain. But something complicated and difficult, like the importance of sea power in the war? Shoved off to a tiny section. Very little coverage of Jutland. Nothing on the blockade, or the Turnip Winter that did so much to bring Germany to its knees. The USN got half a display case, with a single uniform and a pistol, and a brief mention of the presence of the Sixth Battle Squadron with the Grand Fleet. Not even a photograph. And one of the signs, examined in detail, had serious factual errors. Read more...

Recent Comments