Weather has always been of the first importance at sea. In the age of sail, the reasons for this were obvious, but while officers no longer have to worry about the weather gage,1 they still must consider what wind and wave will do to their ships, and to aircraft they may be attempting to operate. And ships today must fight in conditions that would have had Nelson's captains looking to the survival of their vessels.

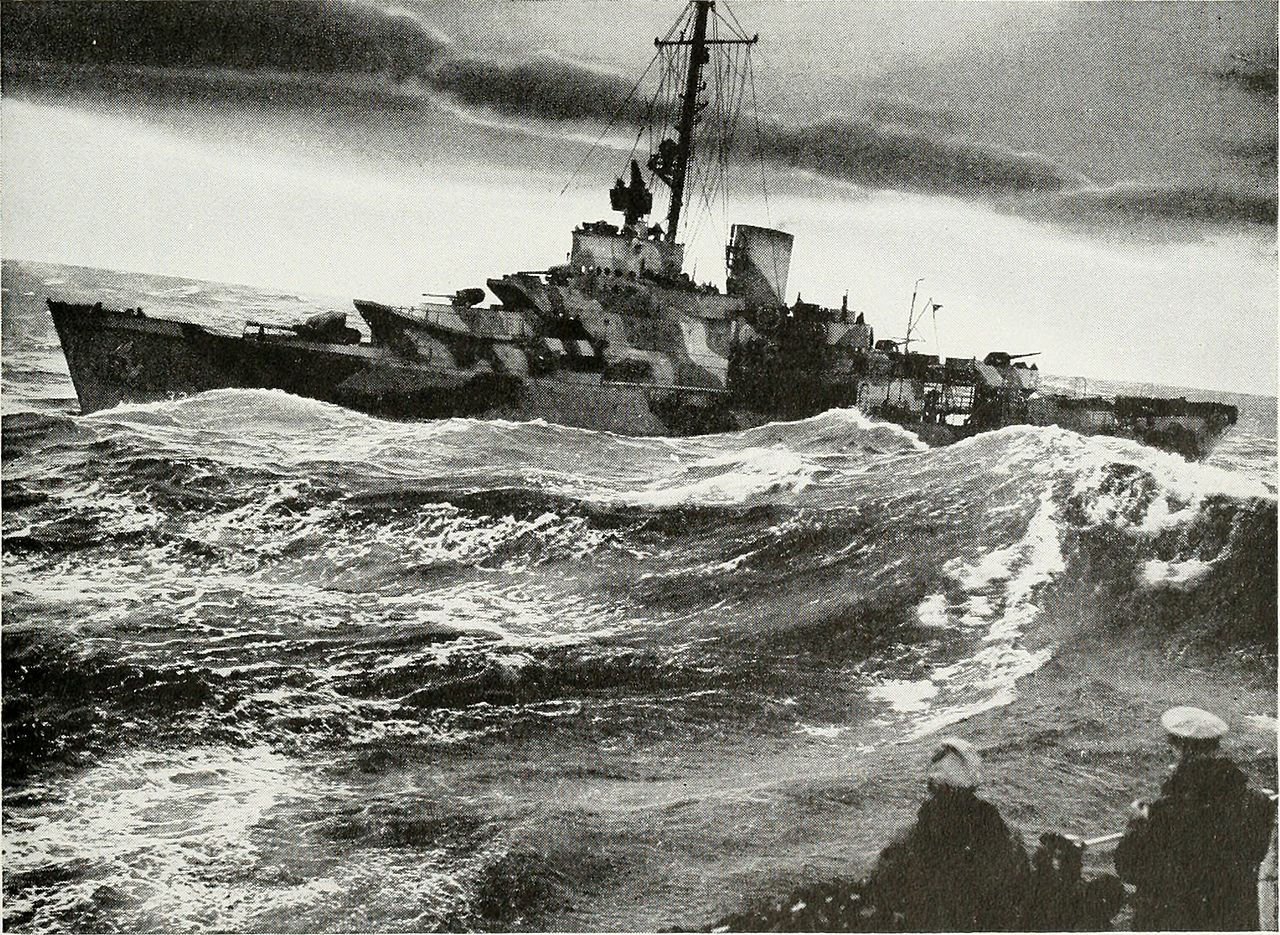

A Coast Guard Cutter battles heavy weather in the North Atlantic during WWII

The biggest effect of weather is on the motion of the ship. Besides the obvious motion of rolling, pitch and heave2 are also important to the efficiency of the crew, although in different ways. Any physical activity, such as loading a gun, is made substantially more difficult in cases of high lateral acceleration. This is only loosely related to the actual angle of roll, as a ship with a large metacentric height might roll to angles nearly as great as a less stable ship, but the lateral accelerations will be substantially higher as it snaps back upright. High roll rates also produce serious problems for fire control, although this is difficult to decouple from the effects of acceleration. Even mechanical systems like modern power-worked guns lose efficiency rapidly in these conditions. Read more...

Recent Comments